Maggie Smith has won two Academy Awards for her performances in “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie” and “California Suite”. She has acted on stage in the UK, Canada and the U.S.. She has many film appearances and once she comes onto the screen, she can command all the attention. She is an actress supreme.

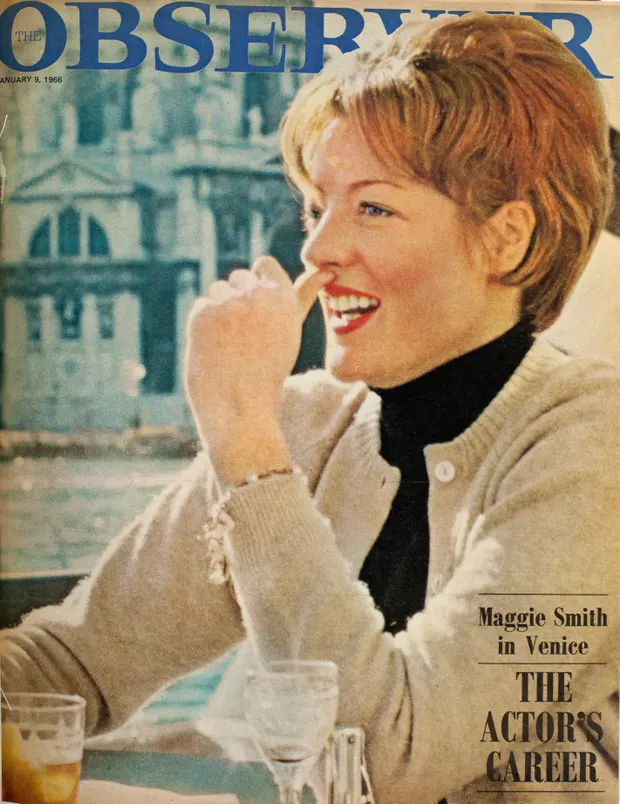

“To the British, there is currently no more delectable comedienne in the world than Maggie Smith. She cares little for films, so the bulk of her work has been confined to the stage with occasional forays into TV. As with Vanessa Redgrave (whom she doesn’t resemble one jot) theatre critics do not seem so much to review her work as write her love-letters. Ronald Bryden wrote in the ‘Observer’ in 1969 ‘ Will it be possible in the future to convey the quality which indisputably makes her a great comedienne?’ Her effects are not of the kind that critics can analyse. Yet unlike the fabled stars of the past, she is earthbound, she is innocent and vulnerable and very much afraid of being found out.

She lives on a perpetual knife edge of inadequacy, from which she distracts us hopefully, by prattling on what is normally a series of non sequiturs (or at least sounds like them)., When she is on a winning streak she cannot disguise her glee – though even then she is likely to go pale with self-doubt. She’s too canny not to know she’s pathetic and funny. That sense of humour seems to desert her as she turns increasingly to drama but the touch and the timing remains as sure”. – Davis Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars – The Independent Years”. (1991)

TCM overview:

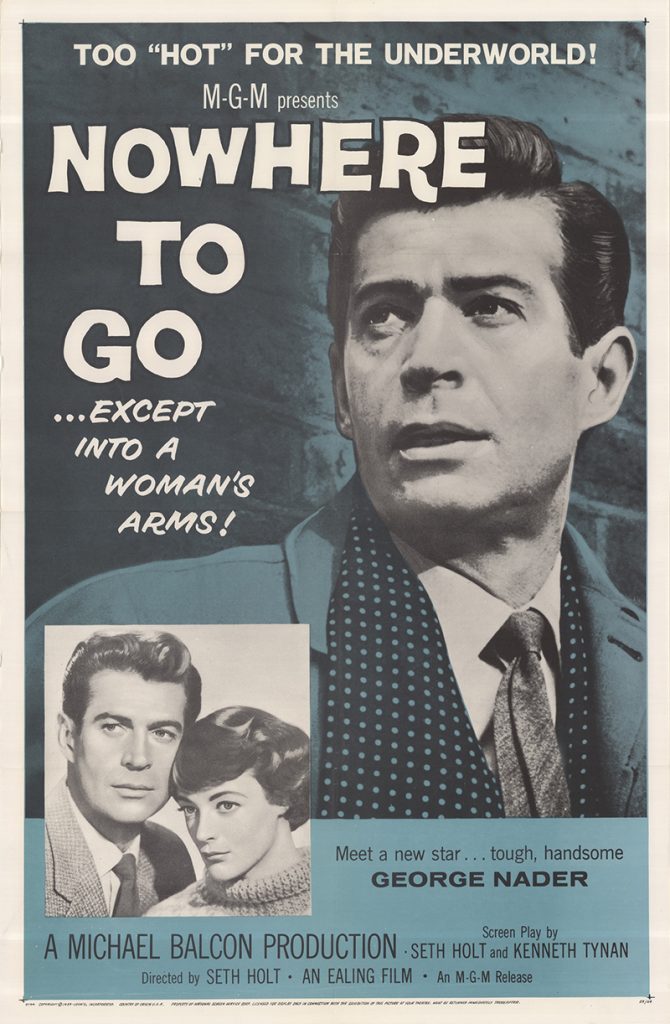

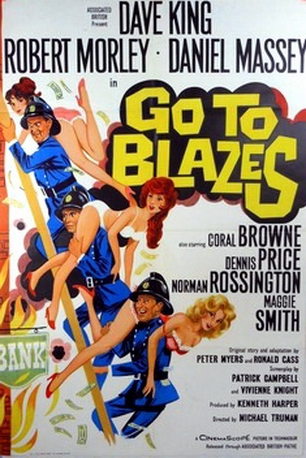

One of the most revered actresses on both sides of the Atlantic, Maggie Smith created a gallery of indelible characters on stage and screen, which ran the gamut from repressed spinsters to comical eccentrics. Smith quickly became an actress of note with performances in several Shakespeare plays before making an auspicious feature debut in “Nowhere to Go” (1959), before stealing the show in “The VIPs” (1963) and gaining international acclaim for her Oscar-winning performance in “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie” (1969). While making her name in dramatic roles, Smith proved equally adept at comedy, particularly with a standout turn as a sophisticated sleuth among an all-star cast in “Murder by Death” (1976). She earned another Academy Award for her brilliant portrayal of a crumbling actress in “California Suite” (1978) before transitioning to a repressed spinster in “A Room with a View” (1986).

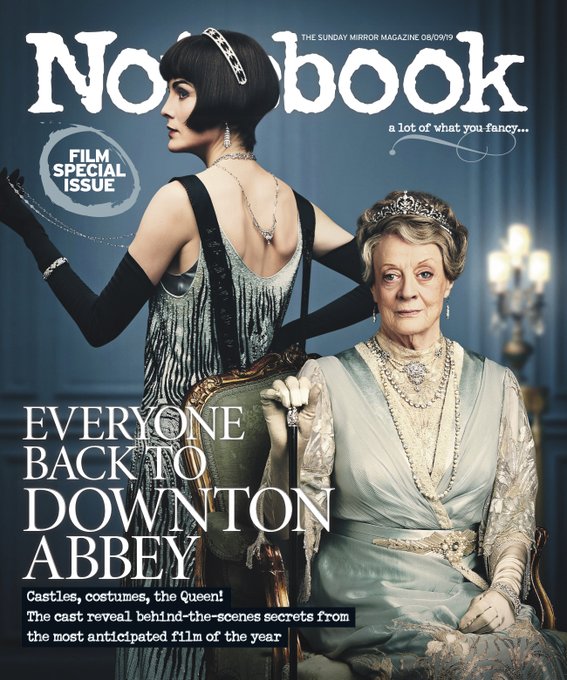

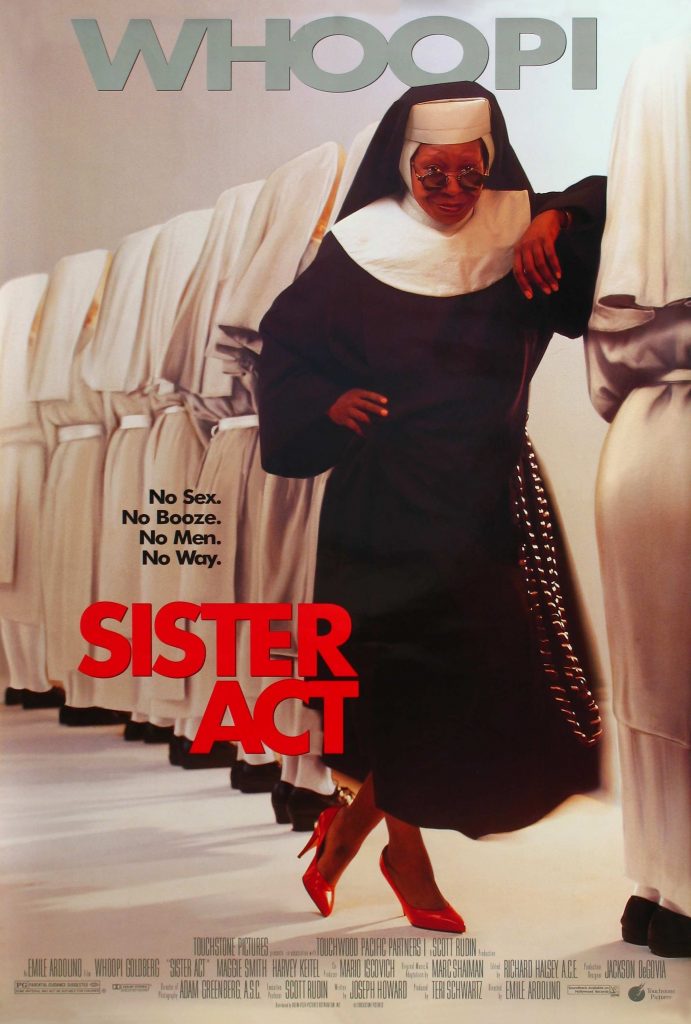

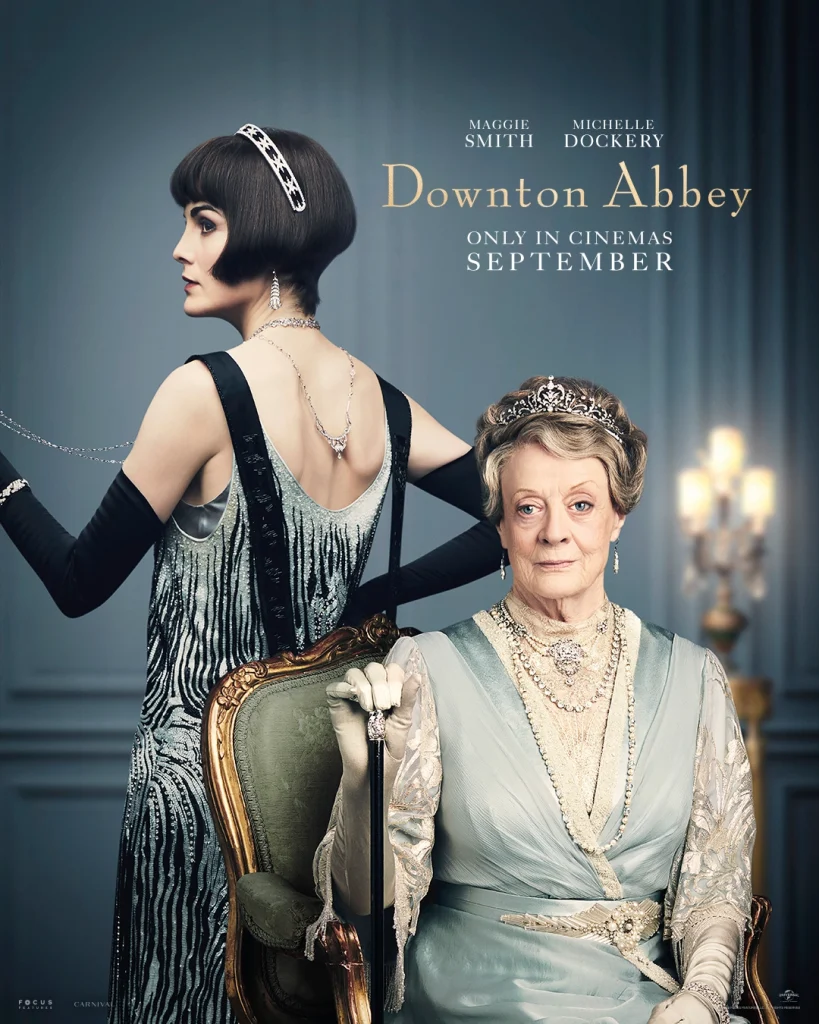

Though she appeared in a supporting capacity in broad Hollywood movies like “Hook” (1991) and “Sister Act” (1992), Smith found comfort on Broadway and London stages while continuing to earn acclaim for smaller films like “Tea with Mussolini” (1998) and Robert Altman’s “Gosford Park” (2001). Smith reached her widest audience with “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” (2001) and its numerous sequels, and earned critical acclaim as Dowager Countess of Grantham on the wildly popular series “Downton Abbey” (ITV/PBS, 2010- ), allowing her the opportunity to impress a whole new generation as she continued to maintain her reputation as one of the greatest actresses of all time.

Born on Dec. 28, 1934 in Ilford, Essex, England, Smith was raised by her father, Nathaniel, a pathologist at Oxford University, and her mother, Margaret. From the time she was eight years old, Smith was determined to become an actress. At age 17, Smith was playing Viola in a production of “Twelfth Night” (1952) and the Oxford Playhouse School, where she also served as an assistant stage manager while studying her craft. Four years later, Smith was singing and dancing on Broadway in the sketch revue “New Faces of ’56” (1956), while making her uncredited film debut as a party guest in “Child in the House” (1956).

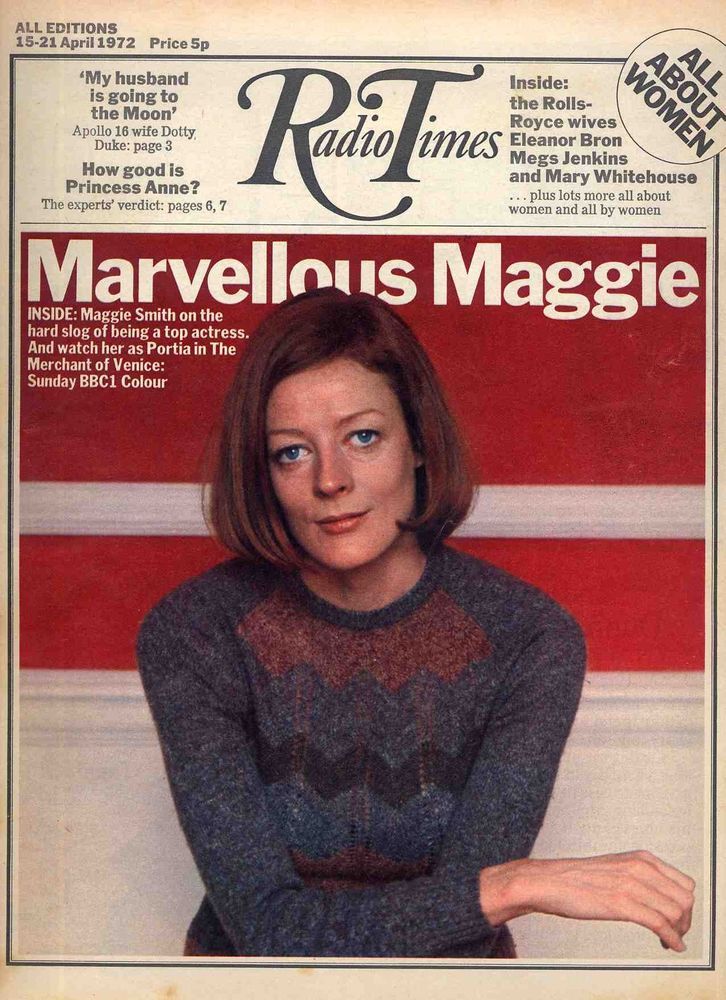

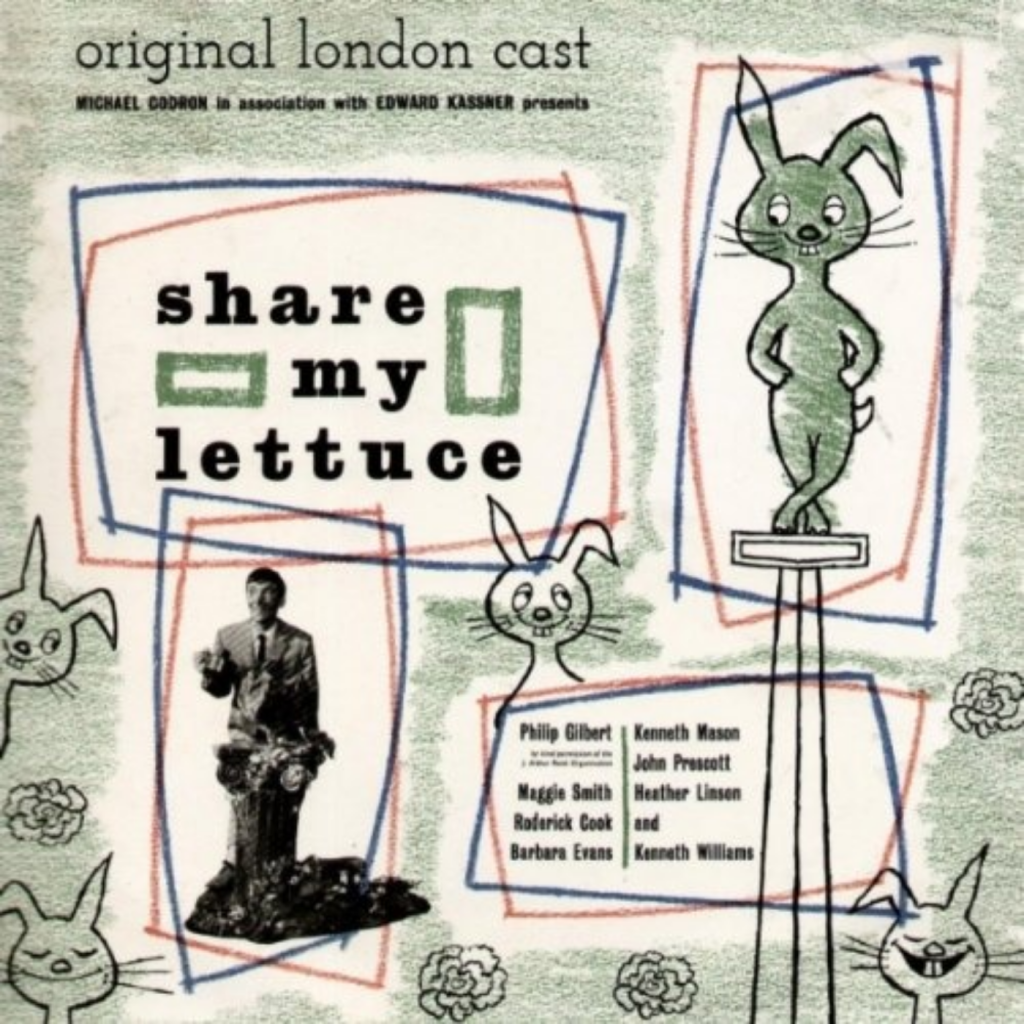

Following her London stage debut in “Save My Lettuce” (1957), Smith made her official film debut in the crime drama, “Nowhere to Go” (1959), which earned her a BAFTA Award nomination for Best Newcomer. Back to the stage once again, she joined The Old Vic Theatre and performed in productions of “As You Like It” (1959) and “Richard II” (1959) before being cast opposite Laurence Olivier for a production of “Rhinoceros.”

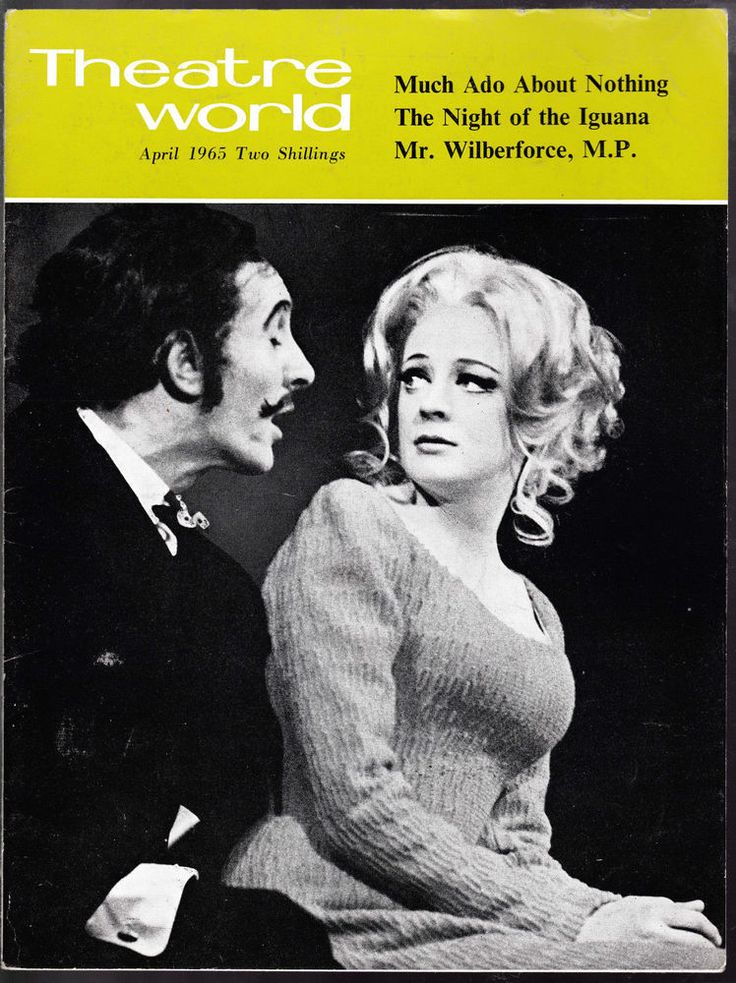

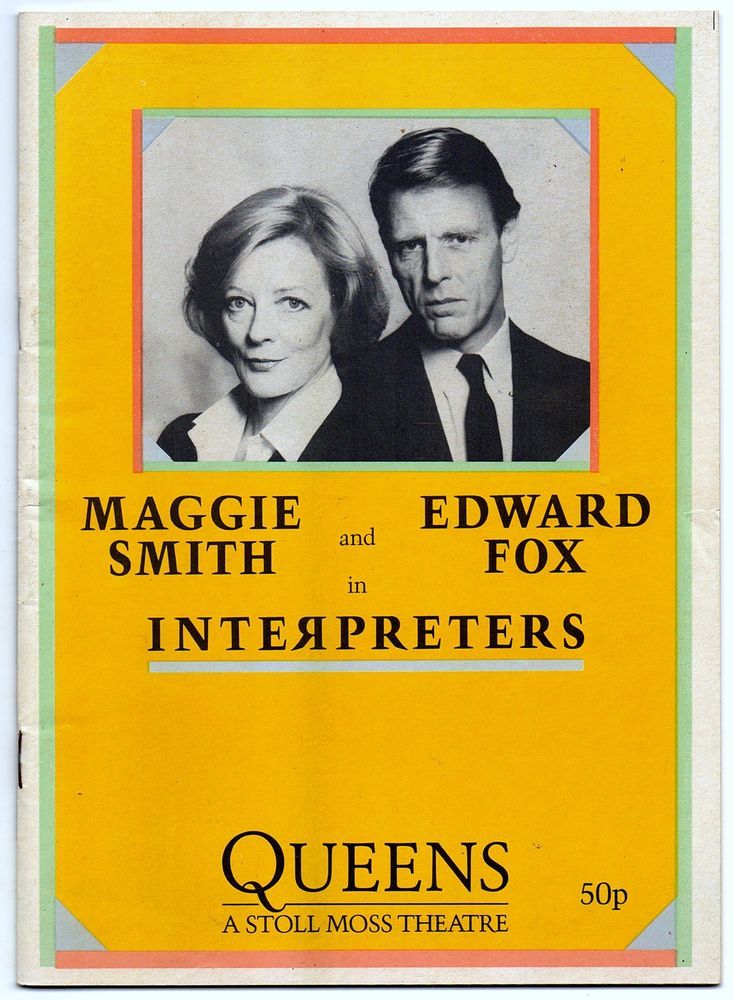

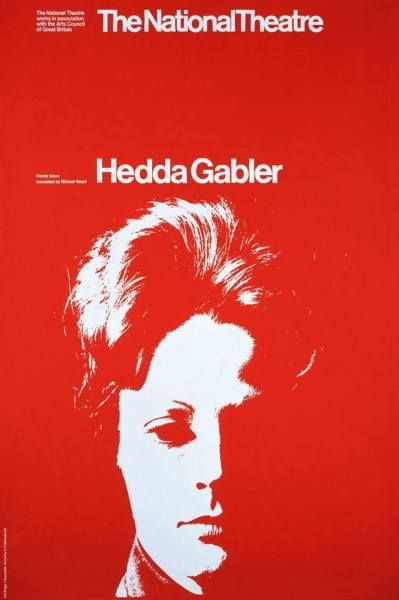

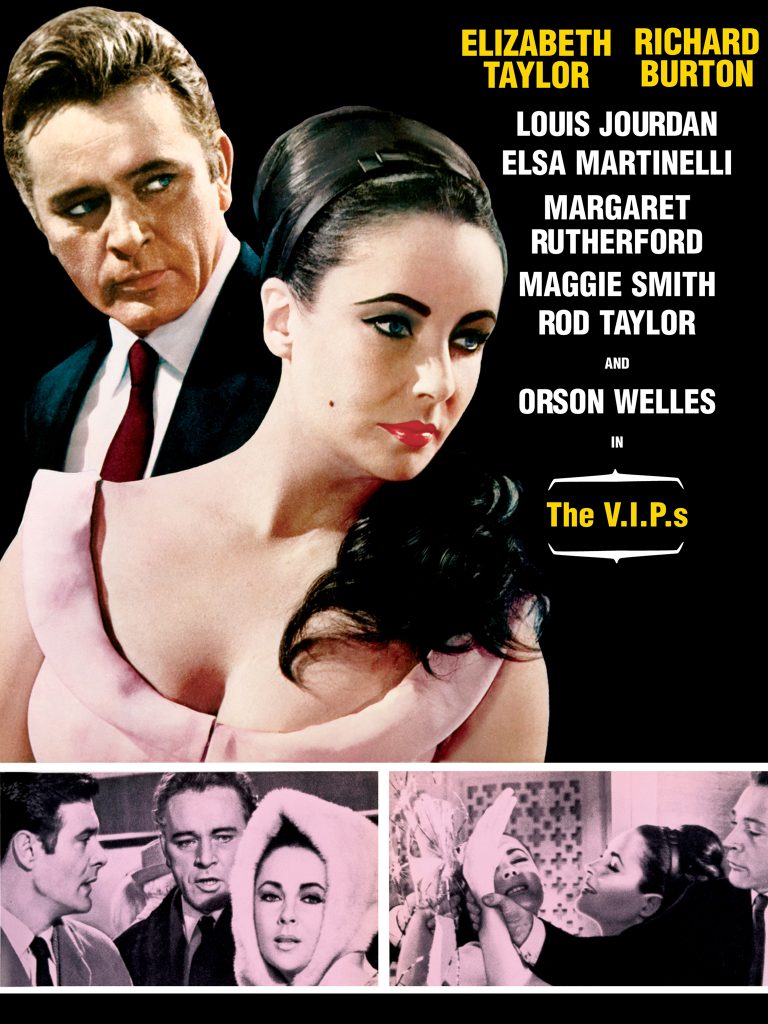

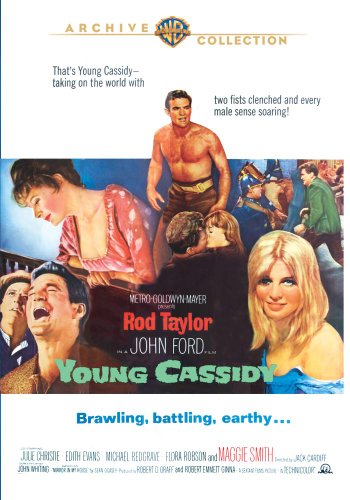

By 1962, Smith was earning her first accolades in the Peter Shaffer double bill “The Private Ear” and “The Public Eye.” The following year, she earned plaudits for her first major film role, playing a love-starved secretary secretly attracted to her boss in “The VIPs” (1963); her stellar performance led co-star Richard Burton to half-jokingly accuse her of “grand larceny.” Also in 1963, Olivier invited her to become a charter member of the National Theatre and cast her as his Desdemona in “Othello,” which she recreated on screen in the 1965 film version, earning her first Academy Award nomination as Best Supporting Actress.

Meanwhile, the 1960s were a heady time for Smith. In addition to building her impressive resume with acclaimed roles, she embarked on a torrid love affair with the still-married actor, Robert Stephens, causing a minor scandal when she gave birth to their first child in June 1967. Following their marriage that same year, she and Stephens ironically co-starred as illicit lovers in “The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie” (1969); critics and audiences were captivated by her performance as a neurotic and fascistic Scottish schoolteacher, which was impressive enough to earn her an Academy Award for Best Actress.

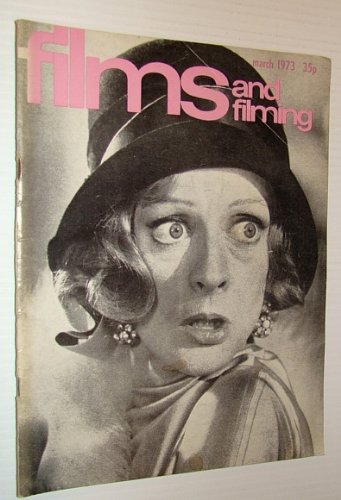

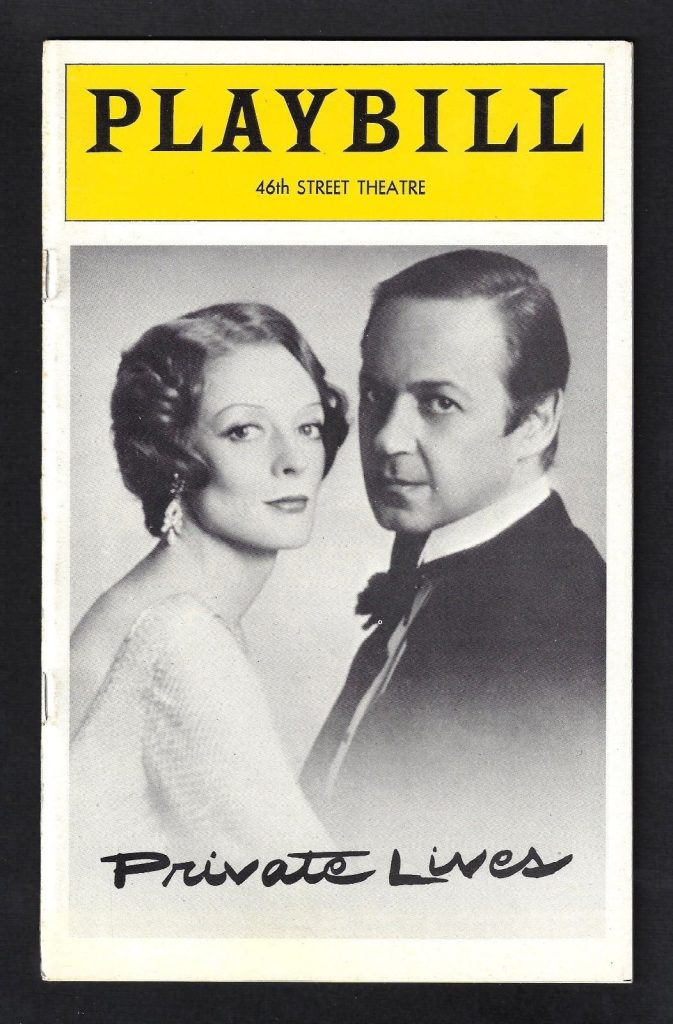

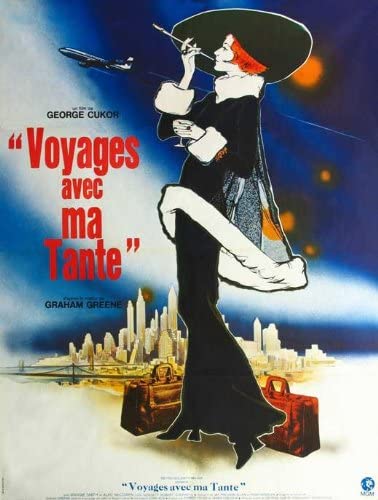

Having taken time out to give birth to a second son in 1969, Smith was back at the top of her game in 1972, headlining a London revival of Noel Coward’s “Private Lives” and starring as the oddball relative sojourning across Europe in “Travels With My Aunt,” a performance that netted her another Best Actress Oscar nomination. Following the collapse of her union with Stephens due to her success and his alcoholism, she embarked on a second marriage to playwright and old beau Beverley Cross, while turning in quality performances in films like “Murder by Death” (1976), an all-star whodunit spoof in which she played the cultured wife of Dick Charleston (David Niven).

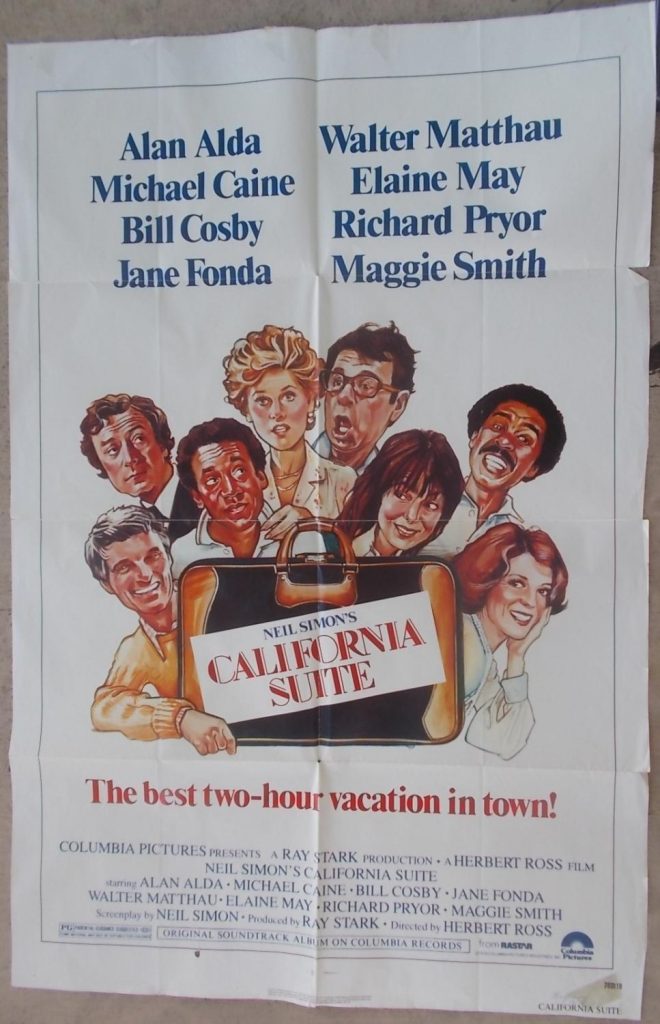

Two years later, she delivered an acclaimed performance in the Agatha Christie adaptation of “Death on the Nile” (1978), before Neil Simon provided her with one of her richest roles in “California Suite” (1978). Smith played Diana Barrie, an insecure British actress coping with a crumbling marriage to her Hollywood husband (Michael Caine) and the spotlight glare brought on by an Academy Award nomination. Although her onscreen character may have lost the coveted statue, Smith took home the Oscar in real life for her nuanced portrayal.

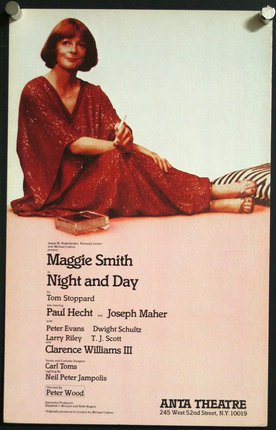

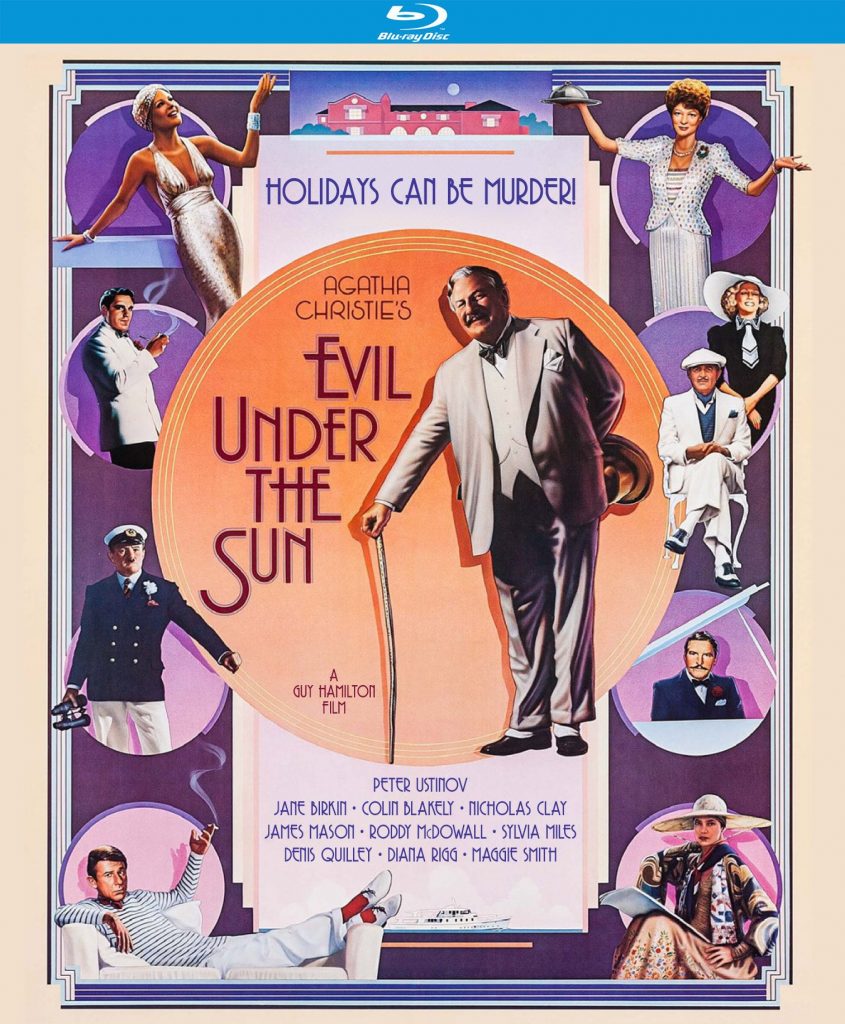

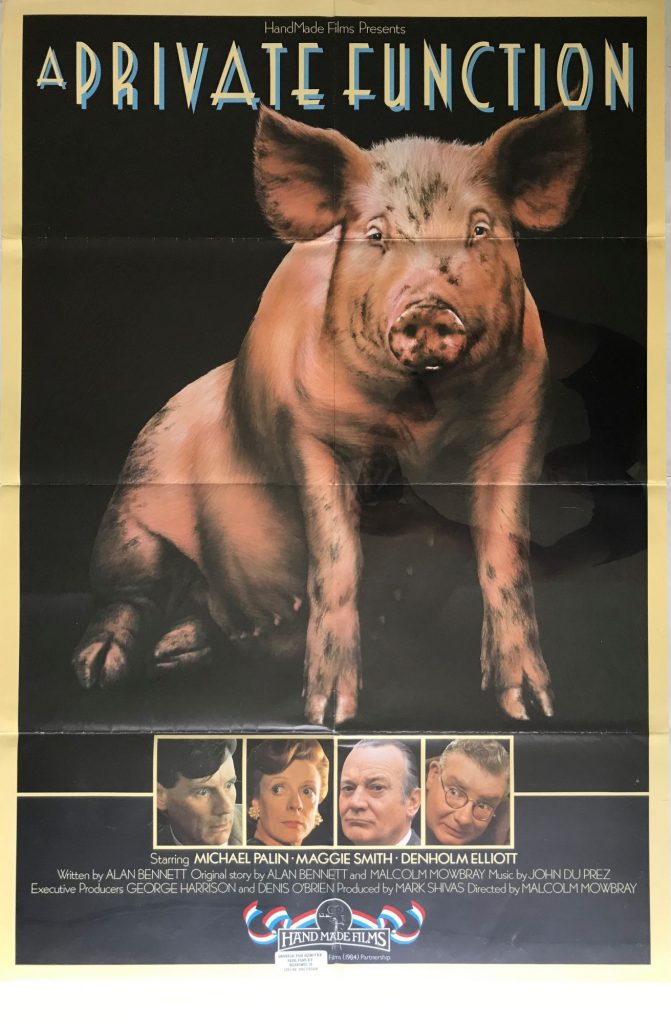

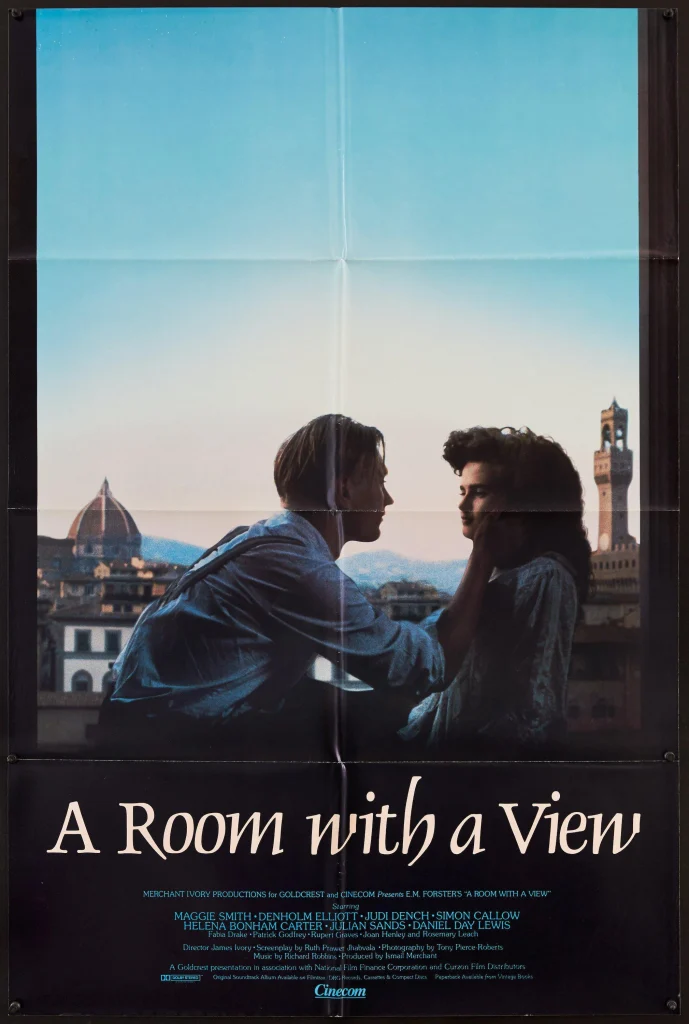

In 1979, Smith returned to Broadway to recreate her London success in Tom Stoppard’s play “Night and Day,” earning herself a deserved Tony Award nomination. After a supporting part in Peter Ustinov’s mildly entertaining “Evil Under the Sun” (1982), Smith proved to be a hilarious foil for Michael Palin in two comedies: “The Missionary” (1982) and “A Private Function” (1984). She excelled as the repressed chaperone who lives vicariously through her young charge (Helena Bonham Carter) in the Merchant Ivory production of “A Room with a View” (1986), in which she displayed her natural ability for delivering witty dialogue with irresistible aplomb and expert timing.

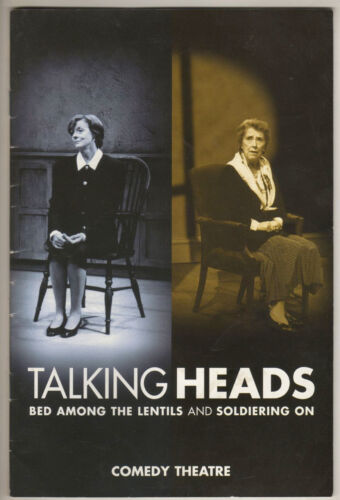

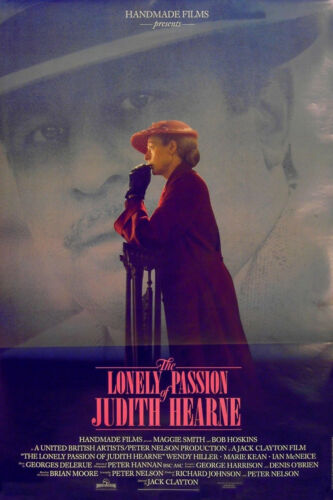

Her performance earned Smith both a BAFTA Award and Golden Globe, as well as an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actress. As the decade waned, she made a rare, but indelible small screen appearance delivering an Alan Bennett monologue in “Bed Among the Lentils,” which was shown on the U.S. “Masterpiece Theatre” (PBS) series. She also had one of her best dramatic roles as the repressed spinster who blossoms when she finds romance with a con man (Bob Hoskins) in the feature, “The Lonely Passion of Judith Hearne” (1987).

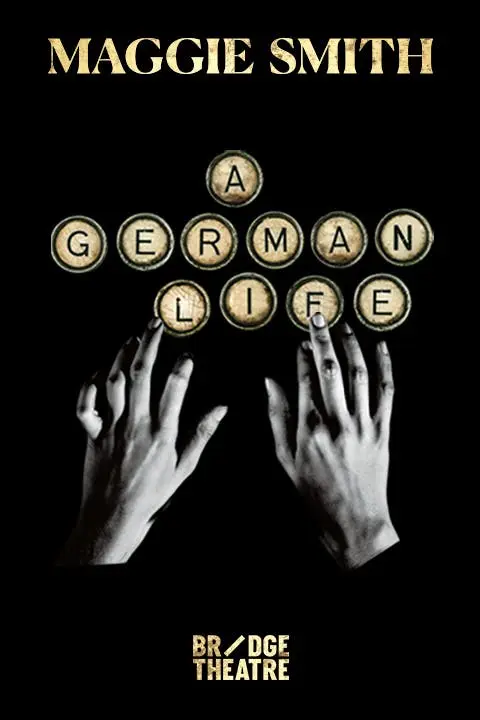

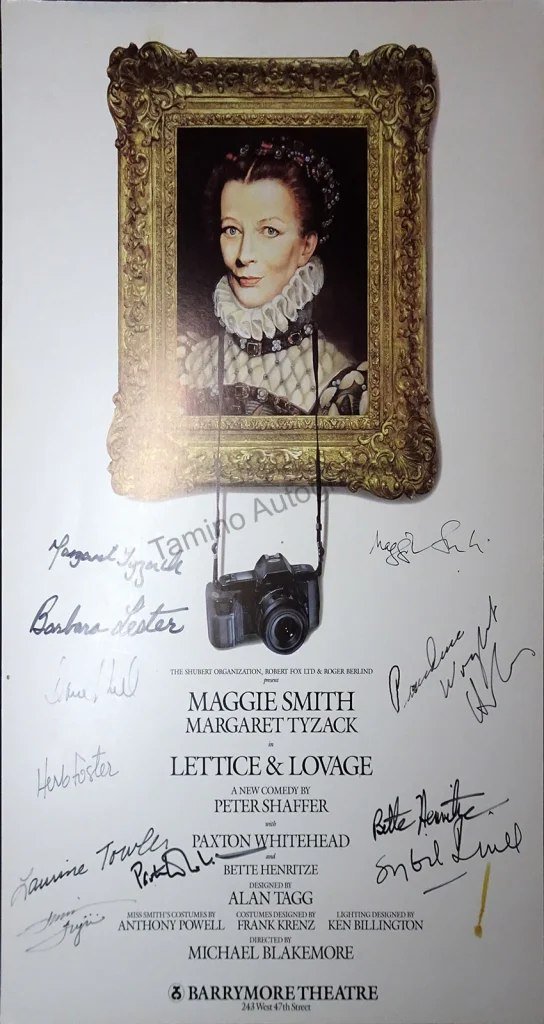

Smith was honored by playwright Peter Shaffer when he tailored his stage comedy “Lettice and Lovage” (1988) specifically for the actress; it proved to be a triumph in both London and New York, and added a Tony Award to her growing trophy collection. In 1990, she was dubbed Dame Margaret Natalie Smith Cross – her full name at the time – by Queen Elizabeth II, after having been named a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1970. Meanwhile, Smith was lovely as the aged Wendy Darling in Steven Spielberg’s misfire, “Hook” (1991), although playing a character much older than herself eventually led to typecasting. For much of the rest of the decade, her onscreen personae tended toward the dour elderly types, ranging from the tart Mother Superior in “Sister Act” (1992) and its sequel, to her Emmy-nominated turn as a Southern matriarch in the small screen remake of Tennessee Williams’ “Suddenly, Last Summer” (PBS, 1993). After playing Layd Bracknell in a highly praised turn in the London stage revival of “The Importance of Being Earnest” (1993), Smith received a BAFTA Award nomination for her portrayal of the no-nonsense housekeeper Mrs. Medlock in “The Secret Garden” (1993).

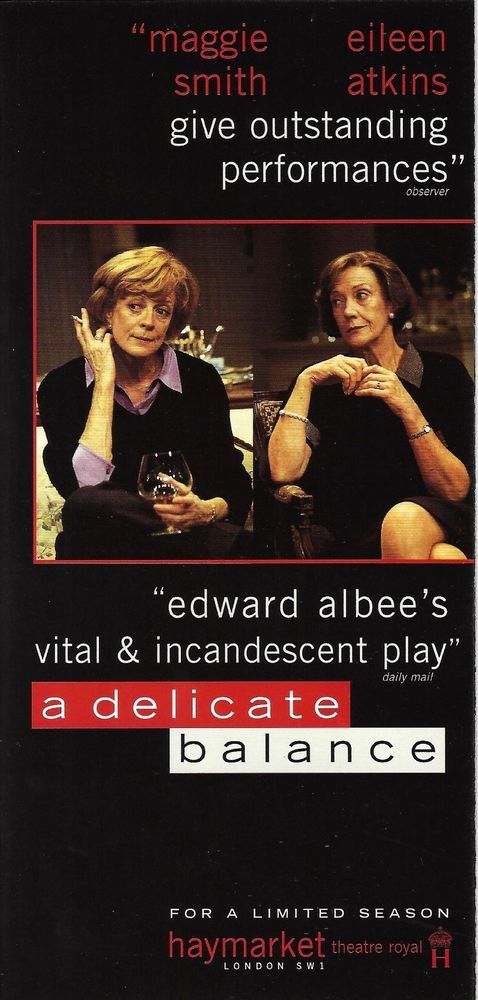

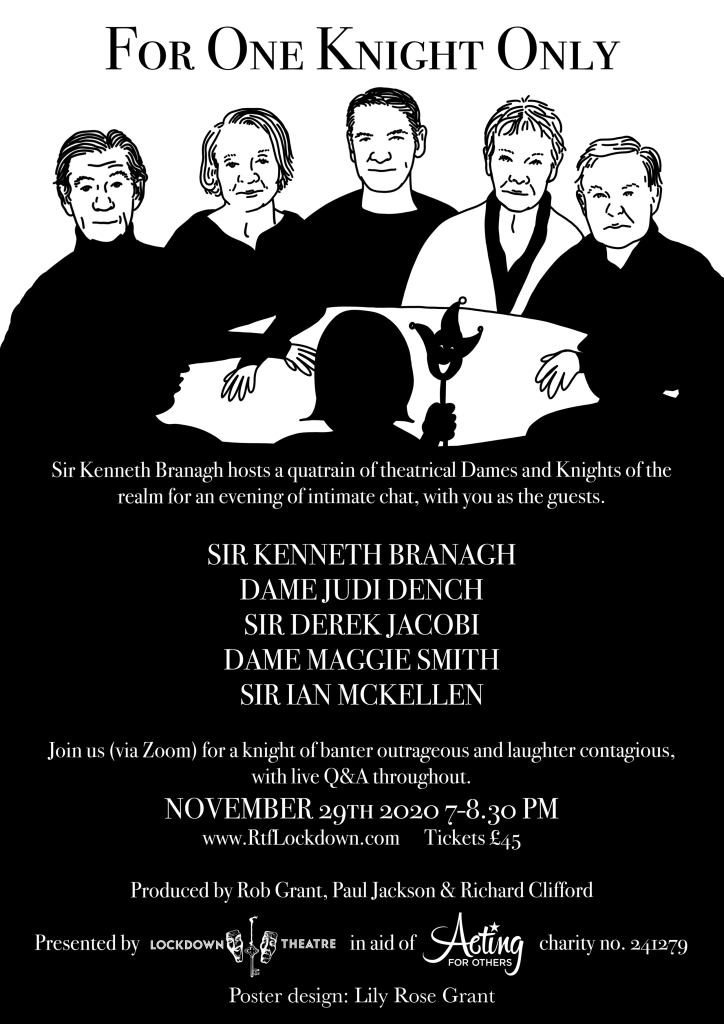

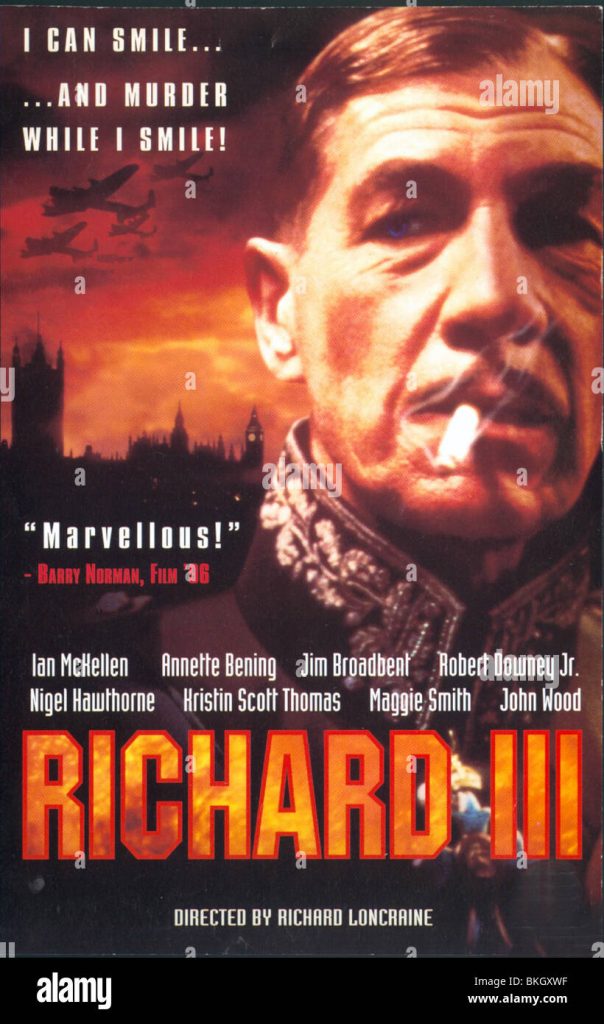

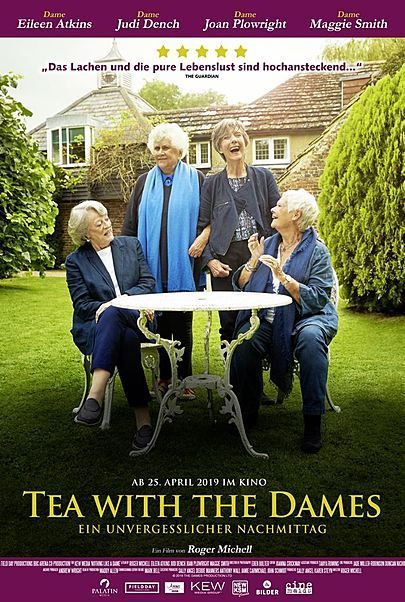

Although she was enjoying a strong career as a character player in films, Smith kept returning to the stage, appearing in several high-profile, critically acclaimed performances, including in the London production of Edward Albee’s award-winning “Three Tall Women” (1994) and as the Duchess of York in “Richard III” (1995), starring Ian McKellan. Following a London stage reprisal of her television role in “Bed Among the Lentils” (1996), she starred in the Albee-penned “A Delicate Balance” (1997), while earning praise for her turn as the meddlesome aunt in the period romantic drama, “Washington Square” (1997). Heading back to the big screen, Smith was impressive as a grande dame in Italy whose misguided admiration for Benito Mussolini recalled Jean Brodie’s admiration of Franco in “Tea with Mussolini” (1998); the film cast her opposite an equally impressive Dame Judi Dench. She earned another BAFTA Award; this time for Best Actress in a Supporting Role. The following year, she was featured as Aunt Betsey in a retelling of “David Copperfield” (BBC, 1999), which netted another Emmy nod after the program aired stateside on PBS.

As the new millennium dawned, Smith brought a poignant sense of loss to her turn as a member of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy in the elegiac “The Last September” (2000). Her next screen role as the stern, shape-shifting Professor Minerva McGonagle in “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” (2001), exposed her to her widest audience to date while earning a legion of new young fans. But it was her turn as the indelible, acid-tongued Constance, Countess of Trentham, in Robert Altman’s clever blend of country house murder mystery and sharp upstairs-downstairs satire, “Gosford Park” (2001), that gave the actress some of her biggest plaudits of her long career. Smith stood out among a massive all-star cast that included everyone from Helen Mirren, Clive Owen and Emily Watson to Kristin Scott Thomas, Michael Gambon and Stephen Fry. For her work, she earned numerous critical accolades, including nods at the BAFTA Awards, Golden Globes and Oscars. Meanwhile, she reprised Professor McGonagle for the sequels, “Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets”(2002) and “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” (2004). After gracing the big screen as one of three bickering women (including Shirley Knight and Fionnula Flanagan) in “Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood” (2002), Smith embarked on one of the most anticipated theatrical events of her career – an on-stage teaming with Judi Dench in David Hare’s new play, “The Breath of Life” (2002), which was reprised on Broadway in 2003.

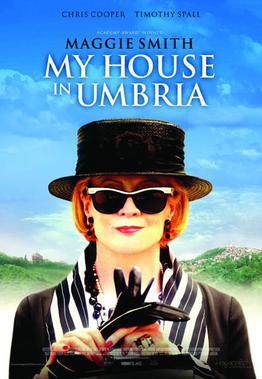

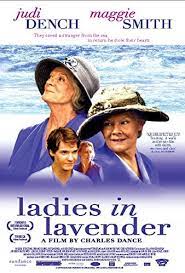

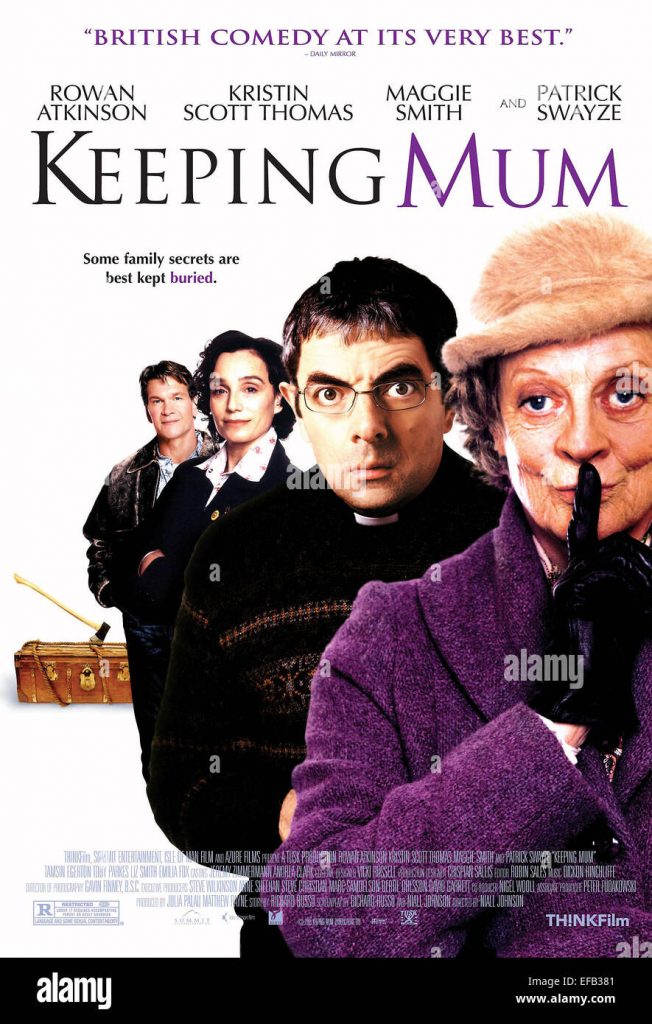

Smith next received an Emmy Award among other accolades for her role in the acclaimed small screen adaptation of William Trevor’s novel, “My House in Umbria” (HBO, 2003), in which she played an English romance novel writer who invites fellow survivors of a terrorist bombing to join her at her Italian villa. Smith next starred in the British-made “Ladies in Lavender” (2004), a period drama in which she played a spinster living with her sister (Judi Dench) in an idyllic coastal town outside Cornwell. Meanwhile, she reprised Professor McGonagle in a more diminished capacity for “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire” (2005), “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix” (2007) and “Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince” (2009). Smith did shine, however, as Rowan Atkinson’s secretive housekeeper in “Keeping Mum” (2006) and opposite Anne Hathaway in the Jane Austen-inspired romantic drama, “Becoming Jane” (2007).

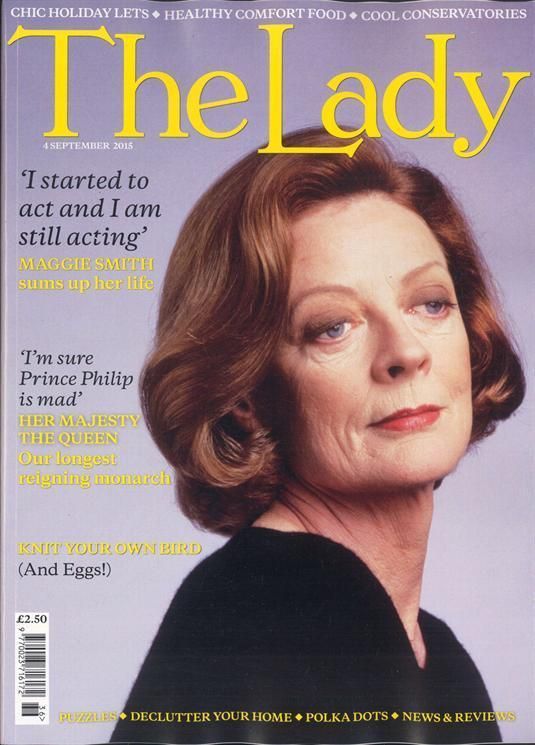

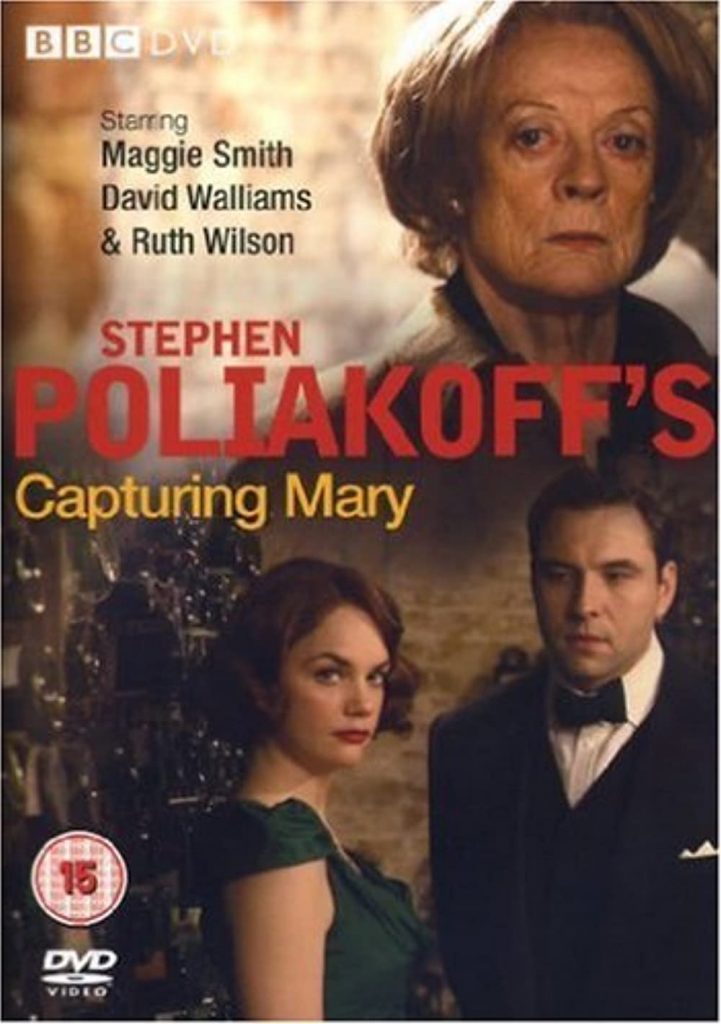

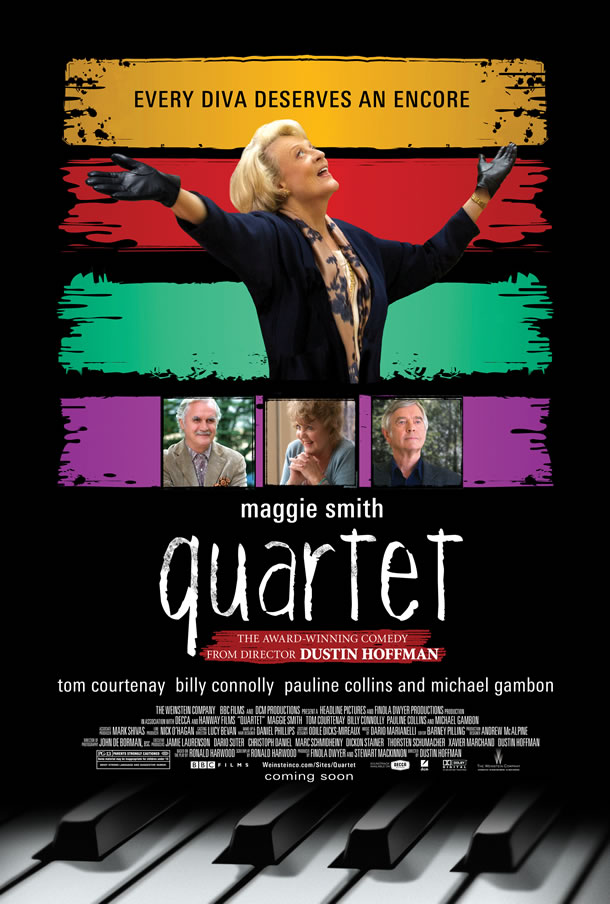

After co-starring alongside Maggie Gyllenhaal and Emma Thompson in the sequel “Nanny McPhee Returns” (2010), Smith earned an Emmy nomination for “Capturing Mary” (HBO, 2010), in which she played a once brilliant writer and critic whose life was destroyed by an evil social climber (David Williams) from her heady youth. Meanwhile, she earned Emmy Awards in 2011 and 2012 for her performance as the sharp-tongued Violet Crawley, the traditional and protective Dowager Countess of Grantham on the British period drama “Downton Abbey” (ITV, 2011). While trading pointed barbs with family and servants on the show, Smith continued making feature films, bringing imbalance to a foursome of opera singers in “Quartet” (2012) – for which she was nominated for a Golden Globe for Best Actress in a Musical or Comedy – and earning critical praise for her performance as a retired housekeeper suspicious of Asians in John Madden’s ensemble comedy “The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel” (2012).

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

Mike McCrann article on LA Frontiers.com:.

The 1969 Academy Awards handed out in April, 1970 reflected great change in American films. There was so much social conflict going on as the War in Vietnam was polarizing the country. It was the era of protest—youth vs. establishment—and the films nominated that year showed that old style musicals and feel good comedies were on their way out. Midnight Cowboy won Best Picture, becoming the first X-rated film to win the award. (After seeing The Wolf of Wall Street, what passed for X in 1969 seems pretty tame today.)

But the old guard still held their ground. John Wayne won his only Academy Award for True Grit. Nobody really thought he gave the year’s best performance. It was more of a career award.

John Wayne had been nominated once before in 1949 for Sands of Iwo Jima, but his greatest performances in the John Ford classics: Fort Apache, The Quiet Man and especially The Searchers had gone unrewarded. Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight had given spectacular performances in Midnight Cowboy, but voters obviously thought John Wayne was way overdue.

The Best Actress race was even more amazing. Three of the performances were great, and the other two memorable in their own way.

Today Dame Maggie Smith is a revered legend. We watch her year after year on Downton Abbey. She collects Golden Globes and Emmys without having to show up.

But back in 1969 Maggie Smith was truly in her ascendancy. Previously she had been nominated for Best Supporting Actress in Olivier’s Othello. Her breakthrough performance came in 1963 when she stole The VIP’s from superstars Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. Playing the lovelorn secretary to sexy Rod Taylor, Maggie Smith was truly moving amid all the melodramatics.

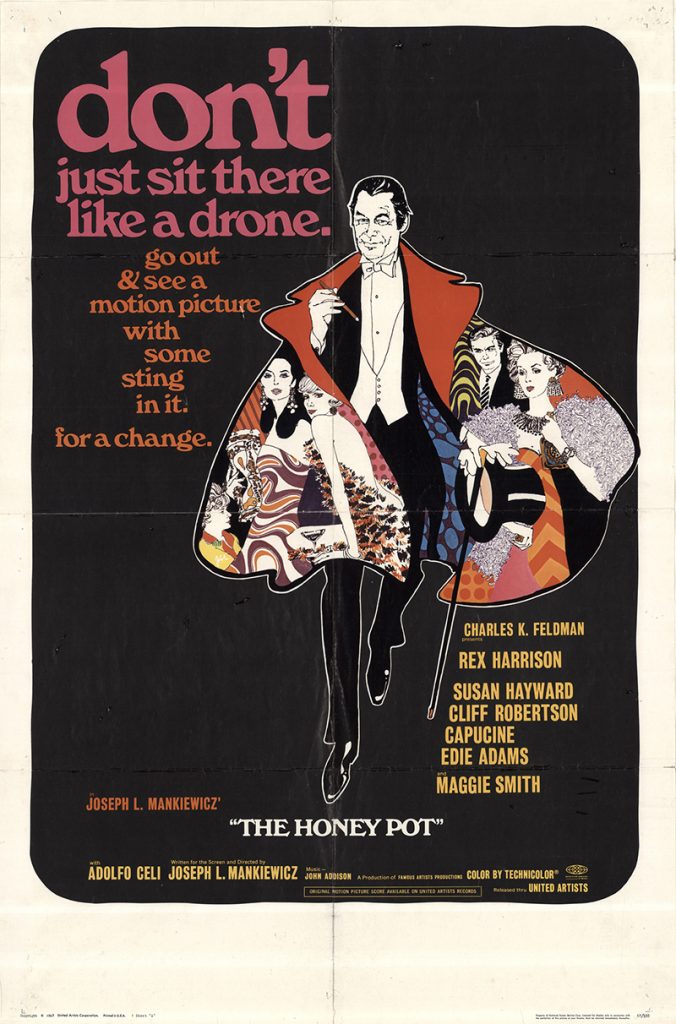

In1967, Maggie Smith committed highway robbery again when she highjacked The Honey Pot from Academy Award winners Rex Harrison and Susan Hayward and French actress Capucine. This late Joseph L. Mankiewicz (All About Eve) comedy is a true classic. Ignored on its release, the wonderful retelling of Volpone is worth seeking out. (Available on Amazon on demand DVD.)

Four of the five nominees were there. The only one missing was Maggie Smith. She was home in England. She wasn’t going to win anyway. Jean Brodie had opened early in the year and was only a modest hit. But Maggie Smith had appeared at The Ahmanson Theater in LA in January and was the critics’ darling. Still nobody thought she had a chance.

When Cliff Robertson announced Maggie Smith, there were audible gasps in the audience. Jane Fonda probably deserved the Oscar, but she had already started her life as a protester and combined with her open use of marijuana, she alienated enough of the old guard Academy to cost her the award.

Liza Minnelli could easily have won her Oscar, but she would never have repeated for Cabaret three years later.

Maggie Smith and Jean Brodie have become one and the same. Beautiful, funny, dominating and always in control, Maggie Smith gave us the template for all the great Smith performances that would follow.

Hollywood royalty was heavily favored in 1969. Liza Minnelli and Jane Fonda were the new Queens of Tinseltown. But Maggie Smith – one day to be Dame Maggie – took the award and never looked back. Maggie Smith has been dazzling audiences for 50 years and we can only hope that she never retires.

This article can also be accessed online here.

“Daily Mail” interview with Maggie Smith can be found here.