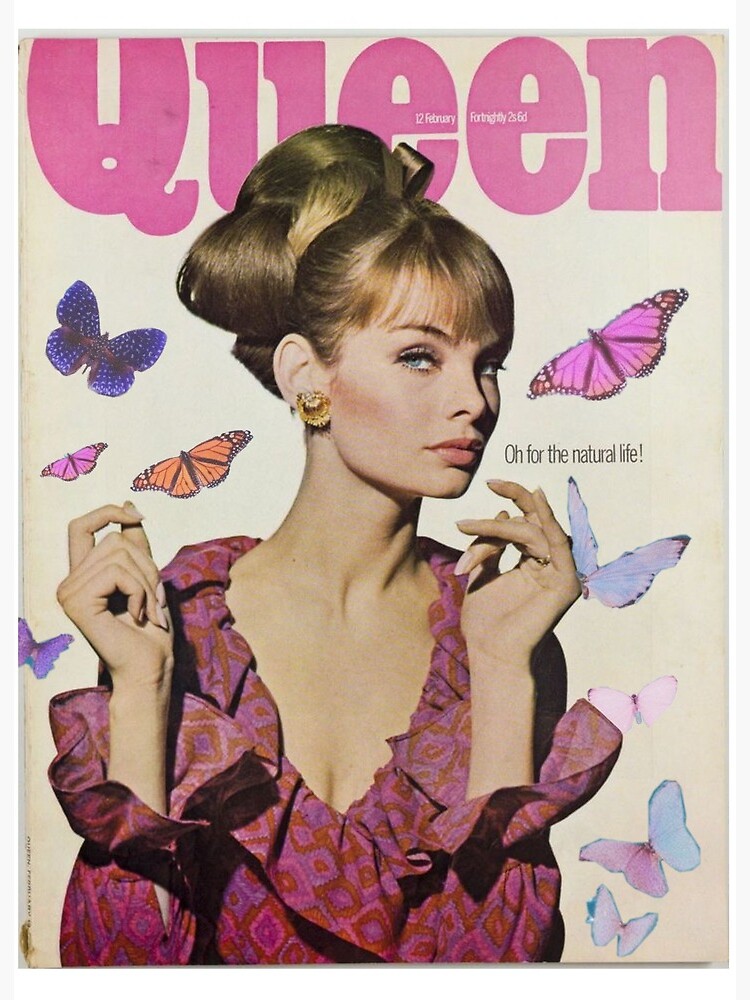

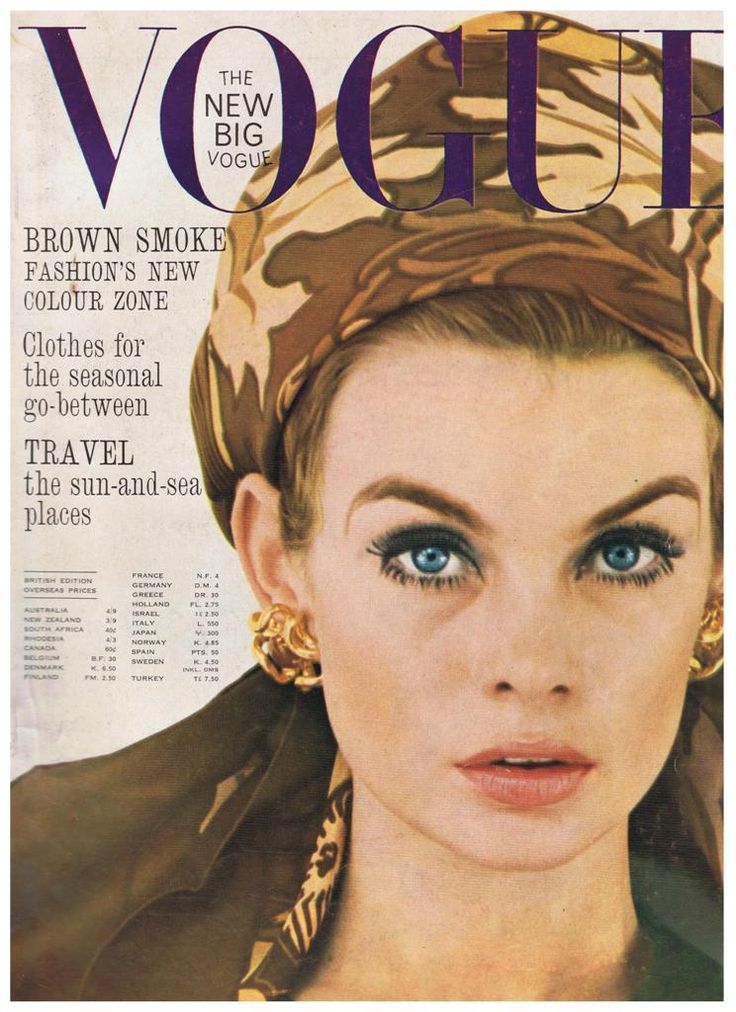

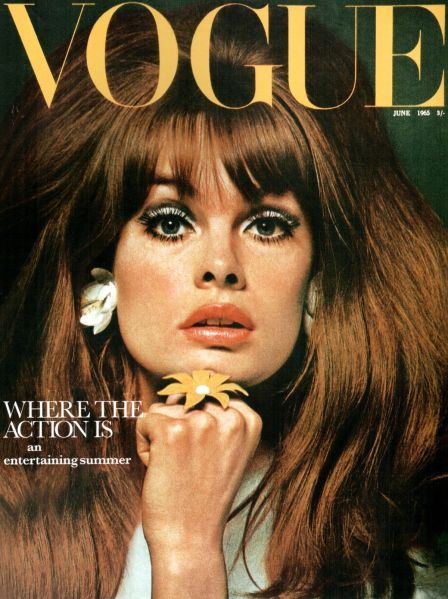

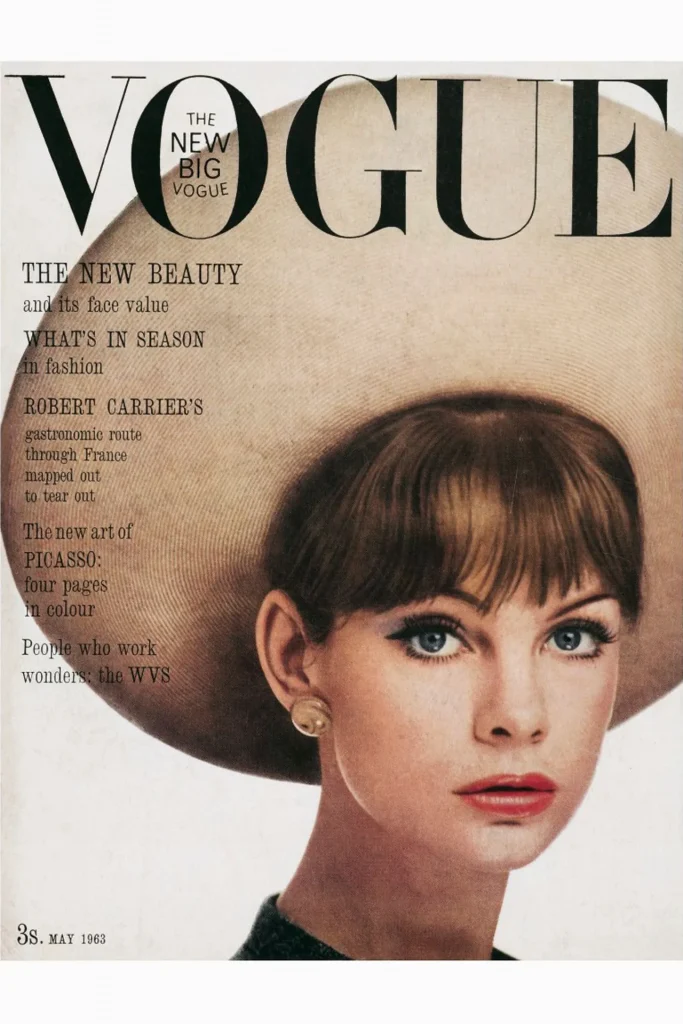

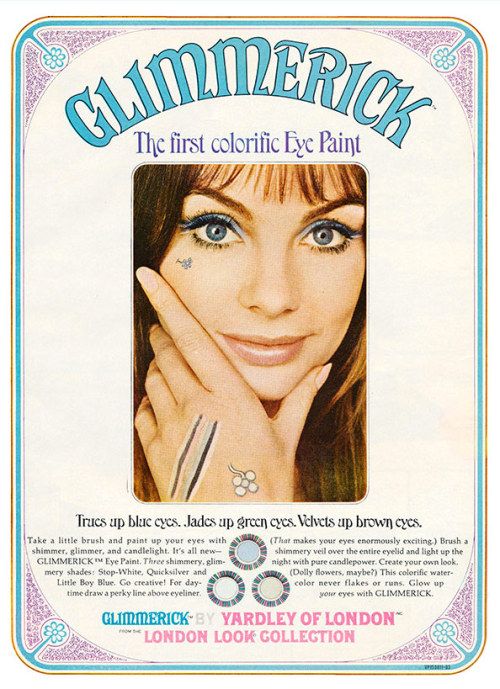

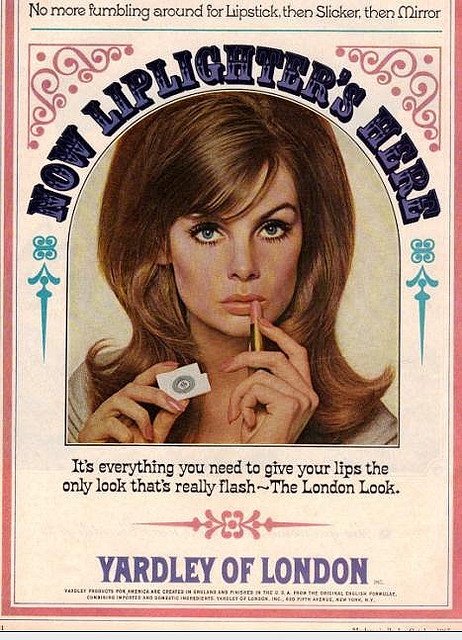

Jean Shrimpton was the top model in the world in the mid 1960’s. She was an icon that represented Swinging London and Caranaby Street. She only made one film which was directed by Peter Watkins and also starred the pop singer Paul Jones. She had retired from modeling in the 70’s and now runs a hotel in Penzance in Cornwall with her family. To view her hotel, “The Abbey”, please click here.

“Guardian” interview from 2011:

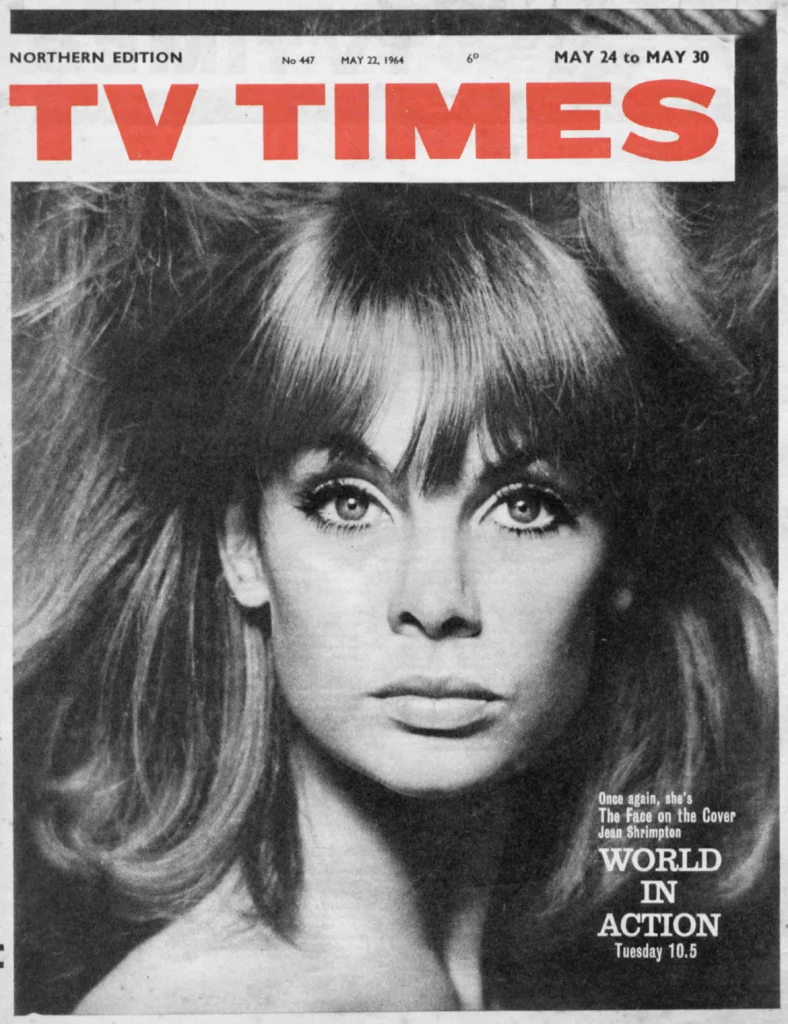

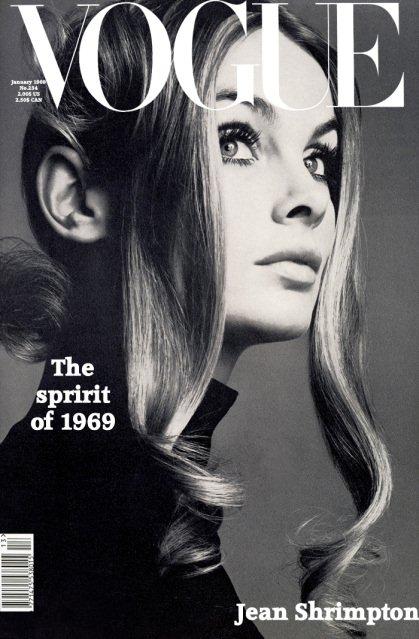

Jean Shrimpton is nonplussed. She has just discovered that Karen Gillan, of Doctor Who fame, is to play her in a forthcoming BBC4 drama about her love affair with photographer David Bailey. Filming of We’ll Take Manhattan, which reprises a heady Vogue photoshoot in 1962, is due to start next month, but the world’s first supermodel could hardly be less interested. “I don’t live my life through the prism of the past,” she says. “I know vaguely about the BBC’s drama, but I don’t look back on my life.” While Gillan chattered excitedly about her delight at “playing somebody who had such a lasting impact on the fashion world”, Shrimpton said she was not in the least bit “bothered” who played her. “It’s of no interest,” she added.

Shrimpton’s lack of enthusiasm about the film is no surprise. She has been reticent to the point of reclusive ever since she quit fashion, once and for all, in her early 30s. A clue to the reasons for her withdrawal from the world that made her famous comes early in our conversation in the drawing room of the Abbey Hotel in Penzance, which she has owned and run for over 30 years “Fashion is full of dark, troubled people,” she says. “It’s a high-pressured environment that takes its toll and burns people out. Only the shrewd survive – Andy Warhol, for example, and David Bailey.” We are talking about British fashion designer John Galliano, who was sacked by Dior last month after allegedly making antisemitic comments. Shrimpton, dressed in a simple, unostentatious black dress – more bohemian than haute couture – is quick to lament the fashion world’s excesses. “No one can condone what he said – it’s reprehensible. But it’s hypocritical to pretend that fashion is normal, that people in it are role models. And it’s stupid to deny that people behave badly.”

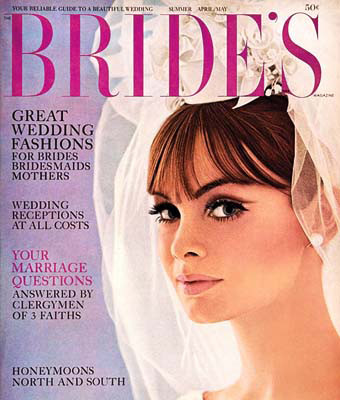

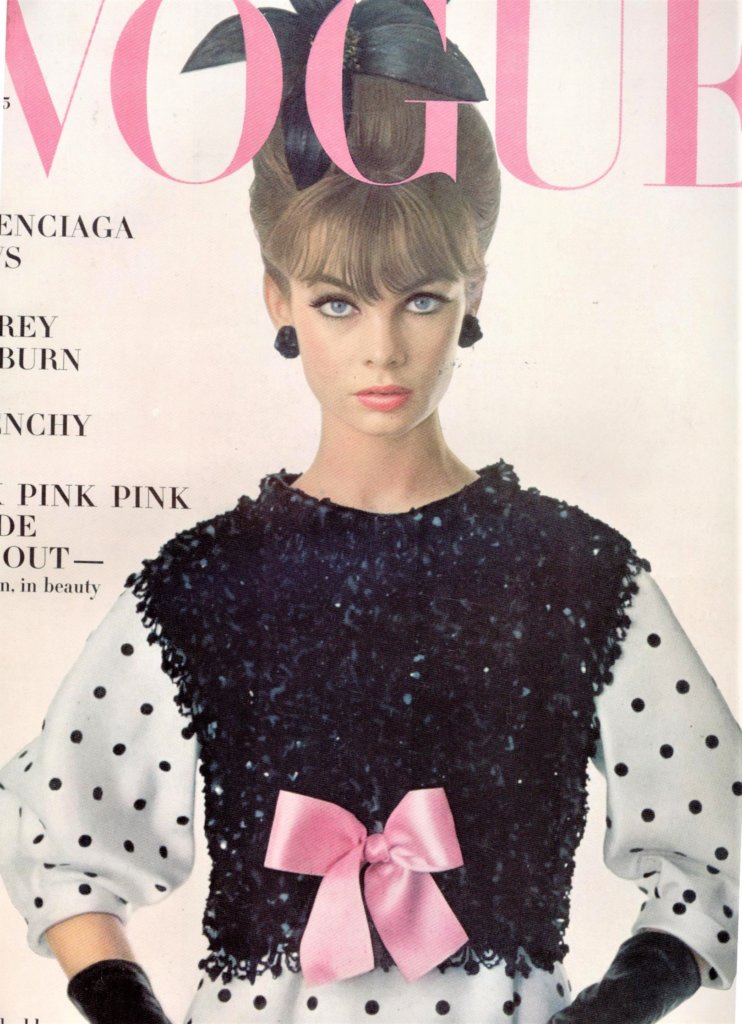

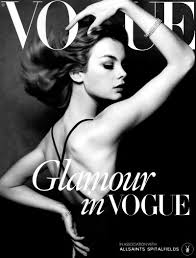

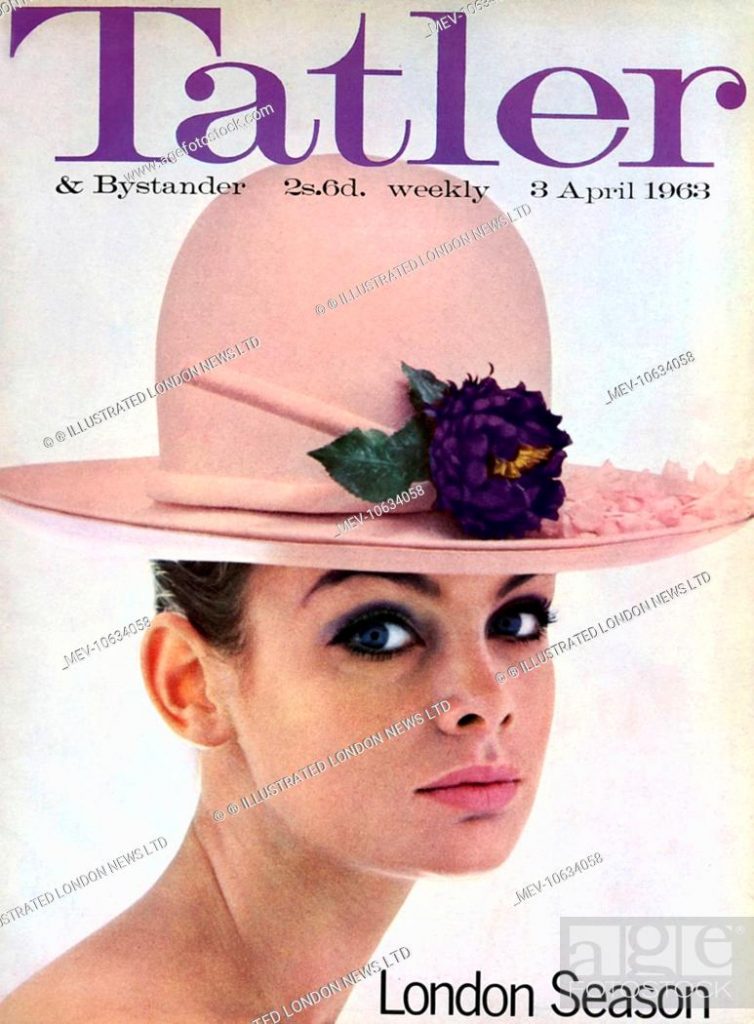

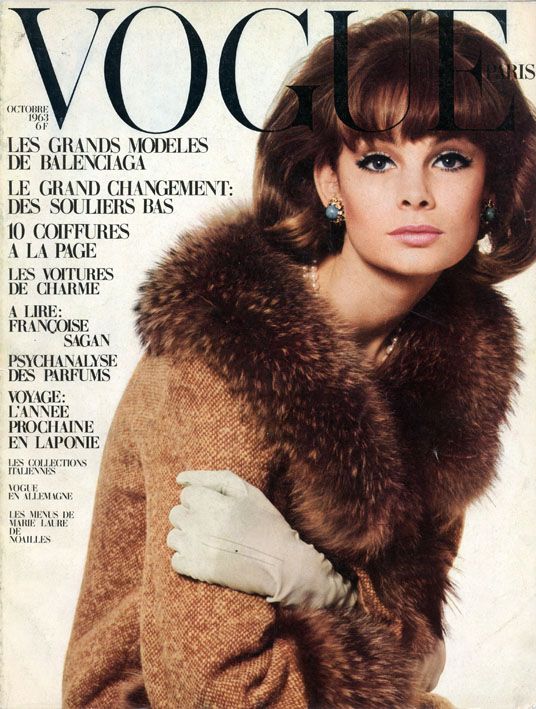

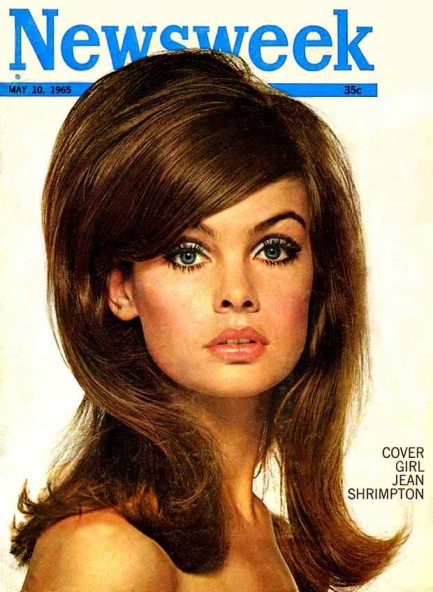

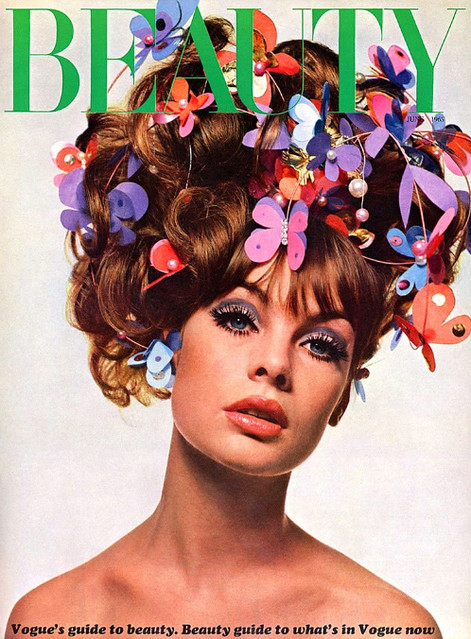

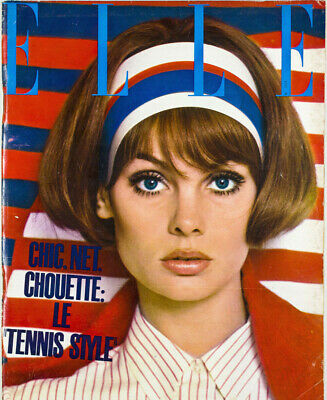

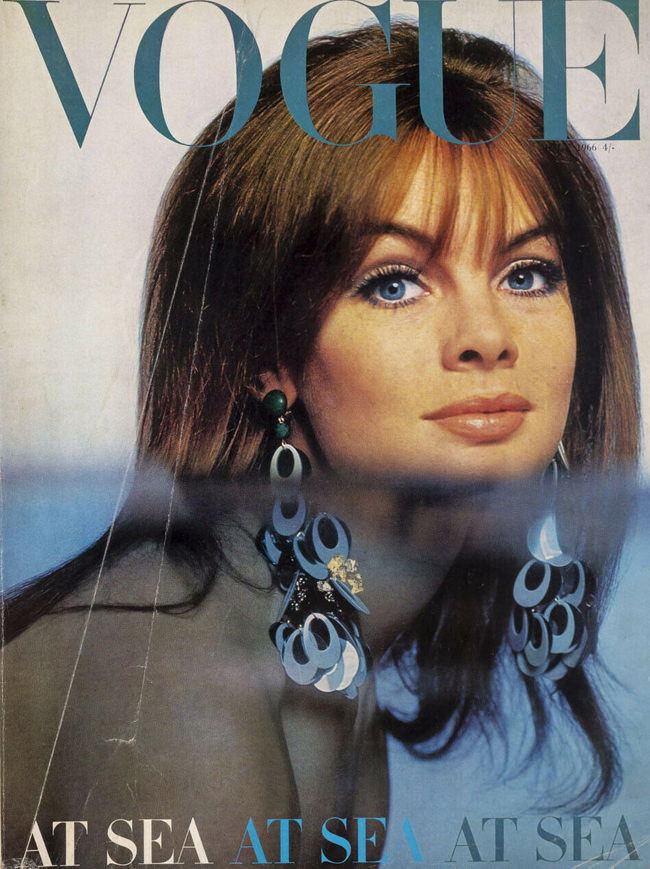

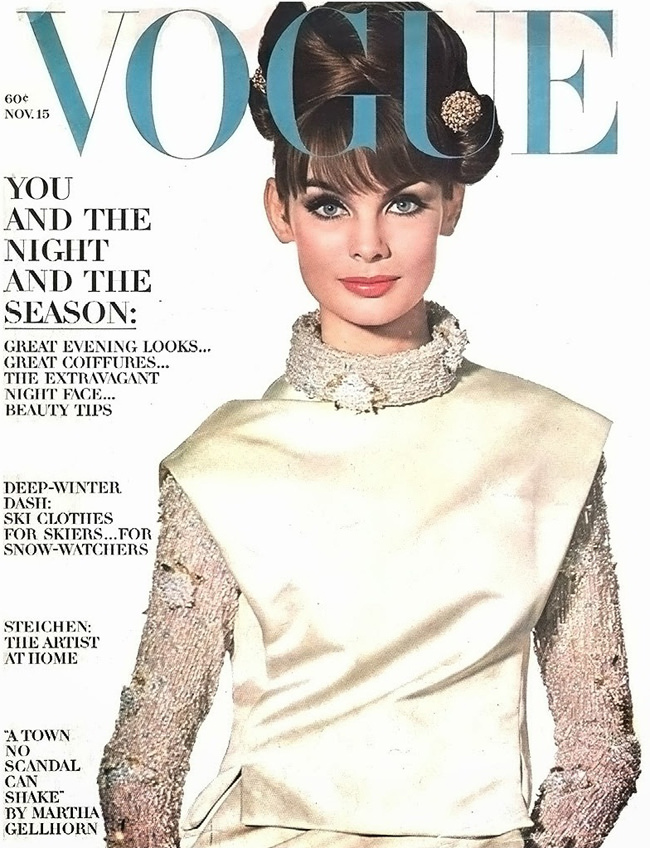

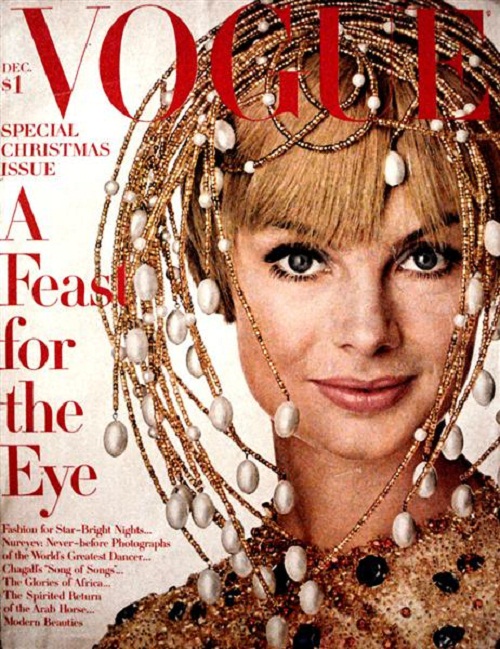

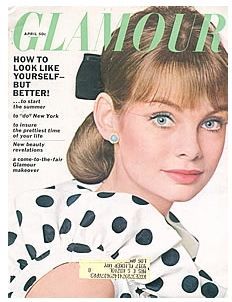

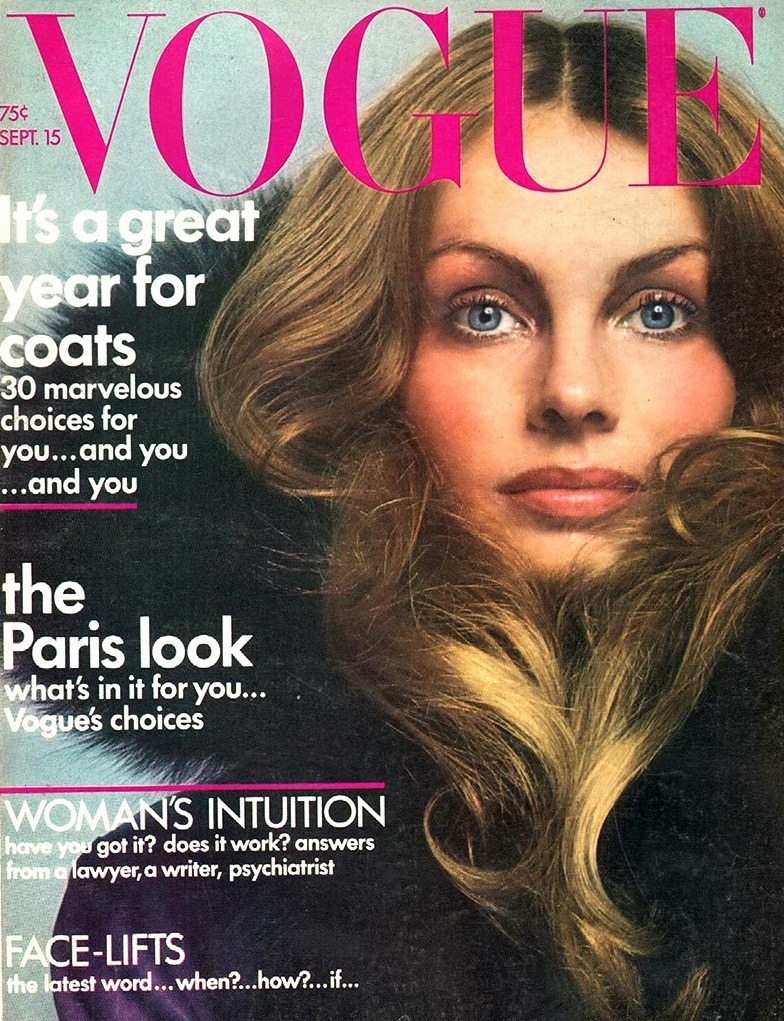

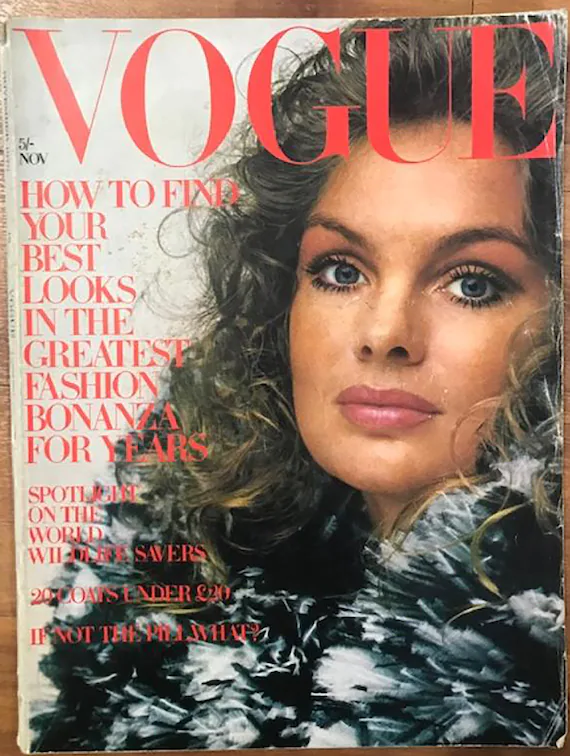

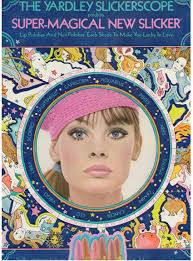

We have heard little of “The Shrimp” since she vanished from swinging London and took off to the West Country. She recently popped up in Channel 4’s Country House Rescue, and in 1990 a ghostwritten autobiography appeared, but Shrimpton makes no bones about why she played ball. “I needed some money to renovate the roof of the hotel,” she says, her blue eyes flashing, arms firmly folded. She adds, curtly: “I didn’t want the book to appear. I’ve hated publicity all my life. I didn’t even like it when I was a model.” So quixotic a statement must be mischievous; after all, Shrimpton travelled the world for a decade, enjoyed a life of luxury and appeared so often on the covers of the likes of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, Vanity Fair, Time and Glamour that she, more than any other model of the 60s, can lay claim to having been the world’s first supermodel. And now, aged 68 and despite, as she puts it, having done “precisely nothing” to preserve her looks, her face is still remarkable – high cheekbones, retroussé nose, arched eyebrows above large, dramatic eyes, and a body as willowy as it was in her heyday. But no, Shrimpton is adamant. “I never liked being photographed. I just happened to be good at it.”

But the High Wycombe-born, 5ft 10in Shrimpton was not merely good at modelling – she was a revelation. Steve McQueen, with whom she was photographed by the legendary American photographer Richard Avedon for American Vogue, quickly spotted her preternatural poise in front of the camera. “You just turn it on and off,” he said, after a photoshoot. Shrimpton shrugged. “I told him it was just my job, and it was. The ability to turn on and off again until the photographer is happy is what all the best models have. It’s an automatic reflex.”

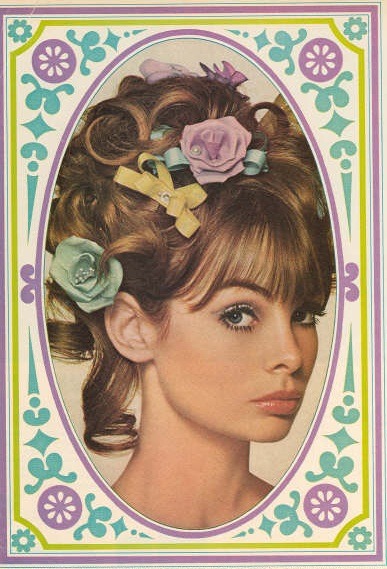

David Bailey was the first photographer to capitalise on this quality, taking an ingenue from Buckinghamshire to stardom almost as quickly as the click of a camera. The pair became emblems of London in the early 60s, but little in Shrimpton’s early life suggested that she was destined for international acclaim. “My upbringing was very rural,” she says. “I was brought up on a farm, surrounded by animals. To this day I can remember Danny, a black Labrador we owned. He was trained by my father to collect eggs and bring them to the kitchen.” She recalls a happy childhood, one in which she lived her life for animals – horses were a passion – and did just enough to get through school, without really feeling that she fitted it. “I was a reserved girl. I was never part of a gang, and yet I wanted to please, too.”

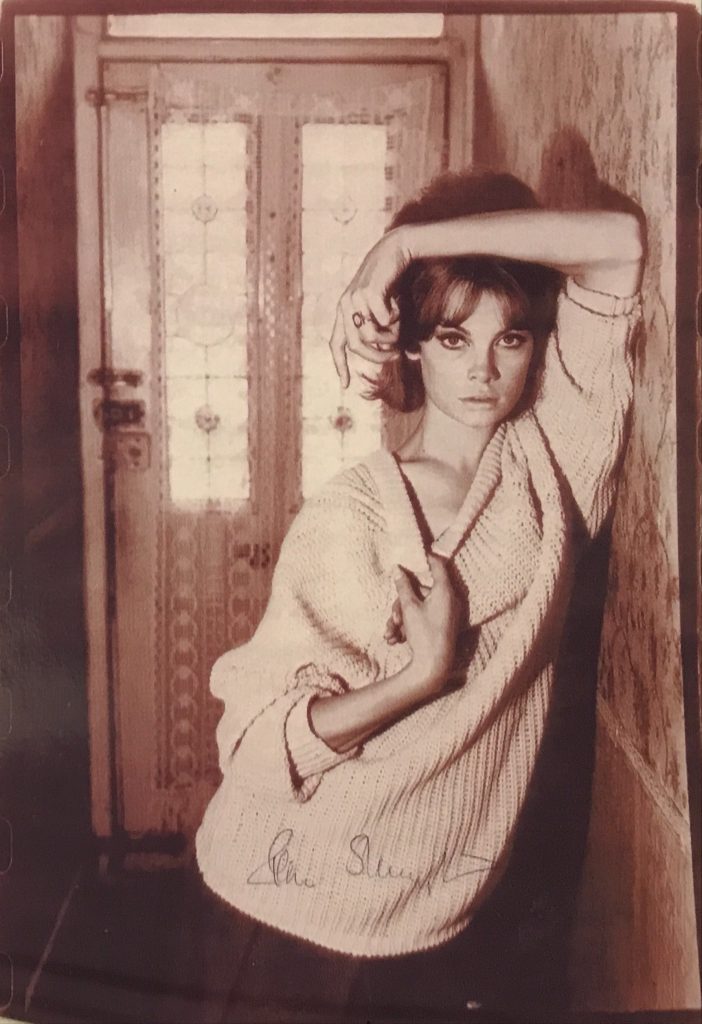

Without any real sense of purpose, Shrimpton enrolled at Langham Secretarial College in London when she was 17. “I managed to get 140 words a minute for shorthand and 70 for typing, just about scraping through,” she says, but already her looks – waifish and coltish, she calls them – had been noticed by the film director Cy Endfield. “I was dawdling at a zebra crossing near Langham Place when an American voice asked if he could talk to me. It was Endfield, and he thought I might be suitable for Mysterious Island, a film he was shooting based on a Jules Verne novel. He told me to go along and see the producer.” Shrimpton, mindful of Lana Turner’s discovery in a drugstore, took up the offer, but Mysterious Island’s producer wasn’t keen. “I left feeling crushed,” she recalls, but took up Endfield’s alternative suggestion – that she enrol on the Lucie Clayton modelling course. Before long, Shrimpton was on Clayton’s books and, while still a teenager, worked as a catalogue model. Magazine work soon came her way, and it was on a shoot for Vogue that she met one of the most influential men in her life, David Bailey. “‘Bailey’ was how he introduced himself,” says Shrimpton. “And that was all I ever called him.” Aged 18, Shrimpton rapidly found herself entwined with the East End boy on the up, who was five years her elder. “We were instantly attracted to each other,” she says. Shrimpton broke off a relationship and Bailey ended his marriage so they could be together. “He was a larger-than-life character, and still is. There’s a force about him. He doesn’t give a damn about anything. But he’s shrewd, too. He made a lot of money out of me.

“I’m not bitter,” adds Shrimpton. “But I’m irked. That’s all. Bailey was very important to me. I’m sure today’s models are a lot more switched-on than we were. Image rights didn’t exist back then. What happened – the creation of the fashion industry – just happened.” Shrimpton’s romance with Bailey did not last long. It was the heady, early days of the swinging 60s and the couple worked tirelessly together, but Shrimpton left Bailey to begin a relationship with Terence Stamp. “Our paths first crossed when Bailey photographed us together for Vogue, and then we met again at a wedding. I was aware of him because he was so good-looking. But it was Bailey who accidentally brought us together. Stamp seemed ill at ease, self-conscious and standoffish, but Bailey talked to him, as he always does with people, and ended up inviting him to come with us to see my parents in Buckinghamshire later that day.”

But if Stamp’s looks captivated Shrimpton, his personality was less straightforward. The beautiful duo were soon an item – to Bailey’s dismay – but their three years together left Shrimpton puzzled. Certainly, there is no love lost now: “Terry has said that I was the love of his life, but he had a very strange way of showing it. We lived together in a flat in Mayfair, but he never gave me a set of keys; one day I walked into his room to talk to him and he simply turned his back on me, swivelling his chair to stare silently out of the window. That sort of thing was typical. He was very peculiar.” Why, then, did she stay with him? “His otherness was a challenge,” is Shrimpton’s reply, but she is deadpan about being one half of London’s most gorgeous couple: “We were two pretty people wandering around thinking we were important. Night after night we’d go out for dinner, to the best restaurants, but just so that we could be seen. It was boring. I felt like a bit part in a movie about Terence Stamp.”

Work, though, was good. By her mid-twenties Shrimpton was known the world over, and she’d also made a major, if unwitting, contribution to fashion when she was hired to present prizes for the Melbourne Cup in Australia. Shrimpton’s dressmaker, Colin Rolfe, was given insufficient fabric, but pressed ahead regardless, making four outfits which were all cut just above the knee. The miniskirt was born – to the shock of conservative Australia at the time.

But for all the fame, the exotic travel and approaches from famous stars such as Warren Beatty and Jack Nicholson – “they’re the kind who can’t help themselves, it’s in their nature, though Jack was more subtle than Warren” – Shrimpton was not happy. She loathed the name “The Shrimp” and felt disenchanted with the fashion world. With hindsight, she says her true self only began to emerge in her next relationship, with photographer Jordan Kalfus, 12 years her senior, in New York. “I discovered museums, art and literature. It was an awakening. There was so much happening in American literature at the time. Mailer, Bellow, Burroughs, Ginsberg – they were all the rage.”

She began to read voraciously, and bought fine art. Back in Britain a turbulent relationship with the anarchic poet Heathcote Williams was followed by another with writer Malcolm Richey, with whom she moved initially to Cornwall. By now, in her early thirties, Shrimpton was only too pleased to forsake modelling completely. She opened an antiques shop in Marazion and took a series of intriguing black-and-white photographs of local Cornish characters. She has never exhibited the images, and has no intention of doing so, but one was of Susan Clayton, then a waitress at the Abbey Hotel. After Shrimpton met her husband, Michael Cox, and became pregnant with their son, Thaddeus, she was told by Clayton that the Abbey might be up for sale.

“I jumped at it,” she says. “If we’d had a survey, we wouldn’t have bought it, and running it has been a labour of love, but it’s been my life for over 30 years.” She and Michael had their reception at the Abbey, a milllion miles from the fashion-world weddings of St James’s. “We had champagne with fish’n’chips, but the only guests were our two registry office witnesses.”

Shrimpton loves the raw, wild beauty of the far west of Cornwall, but does she have any regrets about turning her back on the life she once led? “No,” she says, “but I am a melancholy soul. I’m not sure contentment is obtainable and I find the banality of modern life terrifying. I sometimes feel I’m damaged goods. But Michael, Thaddeus and the Abbey transformed my life.”

Around us, in the Abbey’s drawing room, are the books she and Michael have collected. There is The Rings of Saturn, by WG Sebald; Russian Criminal Tattoo, an outre encyclopaedia; René Gimpel’s Diary of An Art Dealer and a collection of British short stories featuring The Burning Baby, by Dylan Thomas, one of Shrimpton’s favourite works. It’s an unusual collection, not what you’d expect to find in the homes of the likes of Kate Moss. But Shrimpton is a fan. “I like her. She’s a free spirit. Somewhere in herself she’s honest. She’s a naughty girl – but you’ve got to have a few naughty girls.”

More interviews Topics

Models Celebr