Audrey Hepburn obituary in “The Independent” by David Shipman in 1993.

After so many drive-in waitresses in movies – it has been a real drought – here is class, somebody who went to school, can spell and possibly play the piano,’ said Billy Wilder. ‘She’s a wispy, thin little thing, but you’re really in the presence of somebody when you see that girl. Not since Garbo has there been anything like it, with the possible exception of Bergman.’ My generation knew Bergman. Garbo we had never seen. Old pictures were not easy to see in the 1950s. Older cinemagoers talked longingly of Jean Arthur, Carole Lombard, Margaret Sullavan and other enchantresses. From the moment Audrey Hepburn appeared in Roman Holiday (1953), we knew that we had one of our own.

She was born in Brussels to an English banker and a Dutch baroness – and when the war broke out had been trapped in Arnhem with her mother; there they spent the war years, while Hepburn trained as a dancer.

Curiously, several people recognised Hepburn’s particular magic, but few British producers were interested. The revue producer Cecil Landau saw her in the chorus of a West End musical – High Button Shoes (1948) – and engaged her for Sauce Tartare. He liked her so much that he gave her more to do in a sequel, Sauce Piquant. ‘God’s gift to publicity men is a heart-shattering young woman,’ said Picturegoer, ‘with a style of her own . . .’ The magazine mentioned that some people had been to see her perform a couple of dozen times, and among them was Mario Zampi, who was about to direct Laughter in Paradise (1951) for Associated British.

The company’s casting director was equally enthusiastic, but to no avail. She was cast as a hat-check girl: the studio reluctantly allowed her three lines, as against one in the original script. She was signed to a contract, and loaned to Ealing for a couple of lines in the final scene in Lavender Hill Mob (1951), when Alec Guinness is enjoying his ill-gotten loot in South America.

At this point, the producer-director Mervyn LeRoy was looking for a patrician girl to play the lead in Quo Vadis?, MGM’s biggest production in years, and he was excited by Hepburn’s test for him. MGM were not, and the role went to Deborah Kerr. But at last Associated British realised that they might have something in this odd little girl, and they made her a vamp in a parlour-room farce, Young Wives’ Tale (1951), starring Joan Greenwood. It is completely forgotten today, but if you can see it you are likely to be beguiled by two of the most individual actresses who ever appeared in films. They had in common voices with cadences which always alighted on the wrong word to emphasise – as did Sullavan, the other Hepburn, Ann Harding, Irene Dunne, even Judy Garland – turning a statement into a question. In a word, they were never ashamed of their vulnerability; they didn’t seem to be able to cope with life – except to laugh at it. Hepburn’s child-like laugh, deep-throated but tentative, was one of her most distinctive qualities.

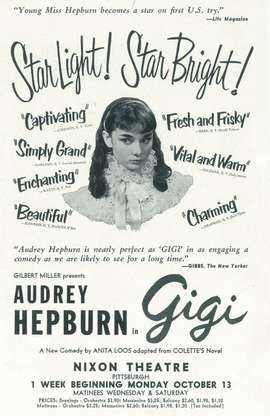

But, obviously, it wasn’t unique. Jean Simmons also had it. And it was Simmons who inadvertently launched Hepburn’s screen career. After Young Wives’ Tale, Associated British loaned Hepburn to Ealing again, to play the sister of the star, Valentina Cortese, in a muddled spy drama, The Secret People (1951), and then to a French company for a minor B-movie, Monte Carlo Baby (1951). Hepburn was doing a scene in a Monte Carlo hotel lobby, when Colette happened by. Colette was then working with the American producer Gilbert Miller on a dramatisation of her novel Gigi, about an innocent youngster being trained to appeal – sexually – to men. This wasn’t a subject show-business wanted to know much about. It wasn’t something Hepburn seemed to know about when she played the role on Broadway in 1951.

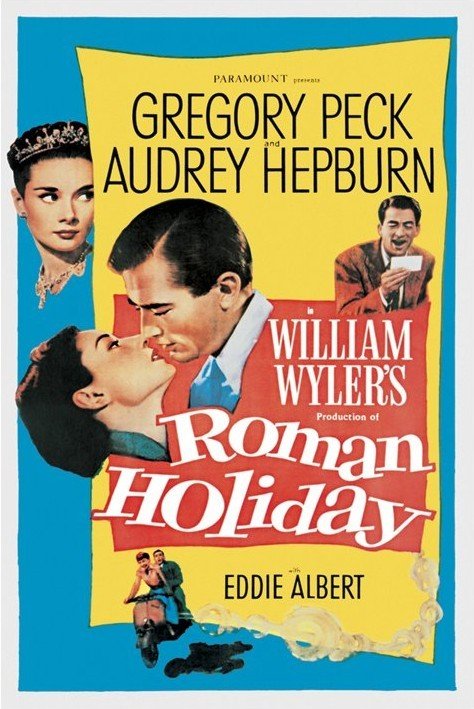

Meanwhile, contractual obligations prevented Simmons from appearing in Roman Holiday, and Hepburn was successfully tested. The property had been brought to Paramount by Frank Capra and when he left it was inherited by another leading director, William Wyler. It was not a likely subject for either of them but then, like many of our favourite movies – All About Eve, Casablanca – there is no other like it; it resists imitation: the innocent alone in the big city. The innocent is the princess of an unnamed European country who escapes from the embassy to see Rome incognito. She is recognised by an American reporter, played by Gregory Peck, who sees in her a good news-story and doesn’t reckon on falling in love.

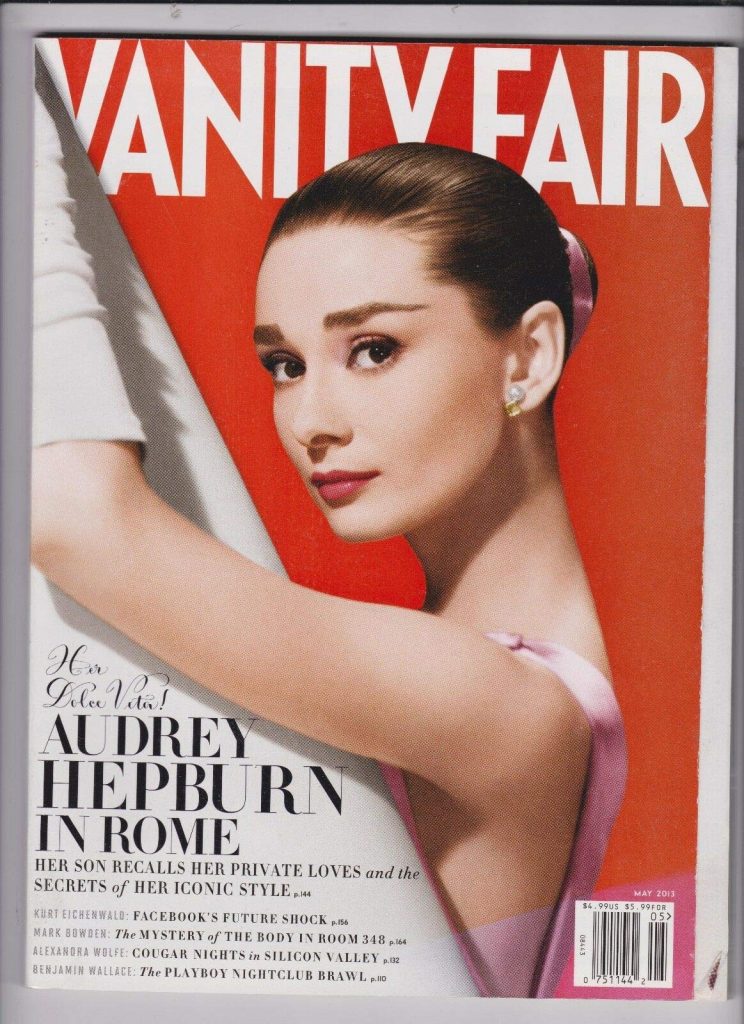

She doesn’t know that he’s a reporter till they are introduced formally at a reception, when by a flicker of an eyelid he indicates that he won’t be filing the story. Peck was not the most adroit of light comedians and the direction was rather academic: but Hepburn’s sheer joy at being free and in love was wonderful to experience. You could never forget her eating an ice- cream on the Spanish Steps or putting her hand in the mouth of the stone lion at Tivoli.

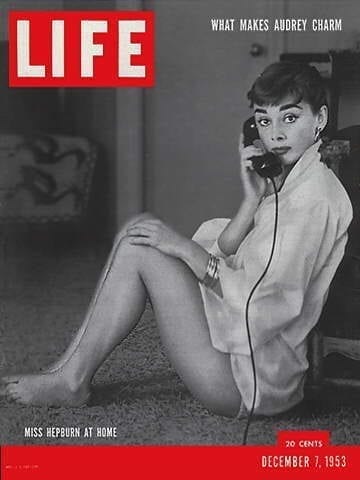

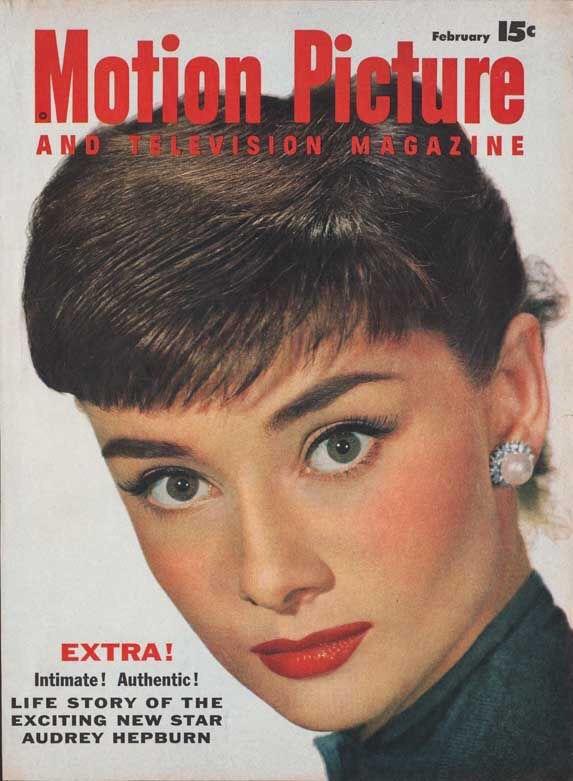

The acclaim that greeted Hepburn was instantaneous and enormous – to be matched only a year later by that for Grace Kelly in what became their decade. Simmons, whom she had never met, telephoned to say, ‘Although I wanted to hate you, I have to tell you that I wouldn’t have been half as good. You were wonderful.’ Hepburn was judged the year’s best actress by the New York critics, by the readers of Picturegoer and by the voters of the Motion Picture Academy. Paramount had Hollywood’s brightest new star – only it didn’t: she was under contract to Associated British, which came to a lucrative agreement by which Paramount had exclusive rights to her services.

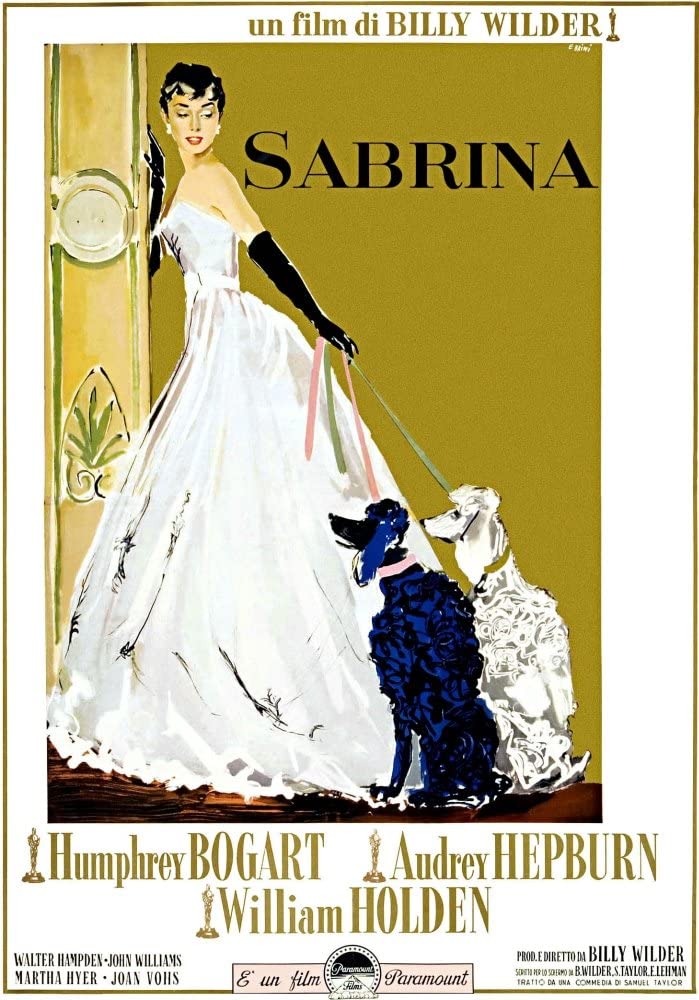

Billy Wilder directed her in Sabrina (1954), in which she was the chauffeur’s daughter, moving from ugly duckling to glamour, which was a formula followed in several subsequent movies. The plot had her loved by two brothers, played by William Holden and Humphrey Bogart. Bogart got her at the end, establishing another pattern to follow, in which she was wooed by men twice her age: by Fred Astaire in Stanley Donen’s Funny Face (1957), Paris fashions and the Gershwins’ music; by Gary Cooper in Wilder’s Love in the Afternoon (1957), Paris again and a rather vulgar remake of Canner’s delicate Ariane; and Cary Grant in Donen’s Charade (1963), Paris yet again and Hitchcockian situations.

You could understand why these actors took the risk of being described as cradle-snatchers. Astaire said: ‘This could be the last and only opportunity I’d have to work with the great and lovely Audrey and I wasn’t missing it. Period.’ Leonard Gershe, who wrote Funny Face, described her as a joy to work with, ‘as professional as she was unpretentious’. Hollywood’s best directors also clamoured to work with her. King Vidor said that she was the only possible choice to play Natasha in the expensive Italo-American War and Peace (1956), causing William Whitebait in the New Statesman to observe, ‘She is beautifully, entrancingly alive, and I for one, when I next come to read (the book), shall see her where I read Natasha.’ But Tolstoy had done the job for him: physically, temperamentally Hepburn was Natasha.

About this time she might have played another literary heroine. James Mason knew that he would make a superb Mr Rochester, but 20th Century-Fox would only proceed with the project if he could persuade Hepburn to play Jane. He didn’t even try. As he explained: ‘Jane Eyre is a little mouse and Audrey is a head-turner. In any room where Audrey Hepburn sits, no matter what her make- up is, people will turn and look at her because she’s so beautiful.’ Of the many films she turned down the most interesting are MGM’s musicalised Gigi, in her old stage role (and the studio was prepared to pay her far more than Leslie Caron, who was under contract, and who did eventually play the role), and The Diary of Anne Frank, George Stevens’s version of the Broadway dramatisation. She said that that would have been too painful after her own experience of the Occupation (in the event the role was so disastrously cast that the film failed both artistically and commercially).

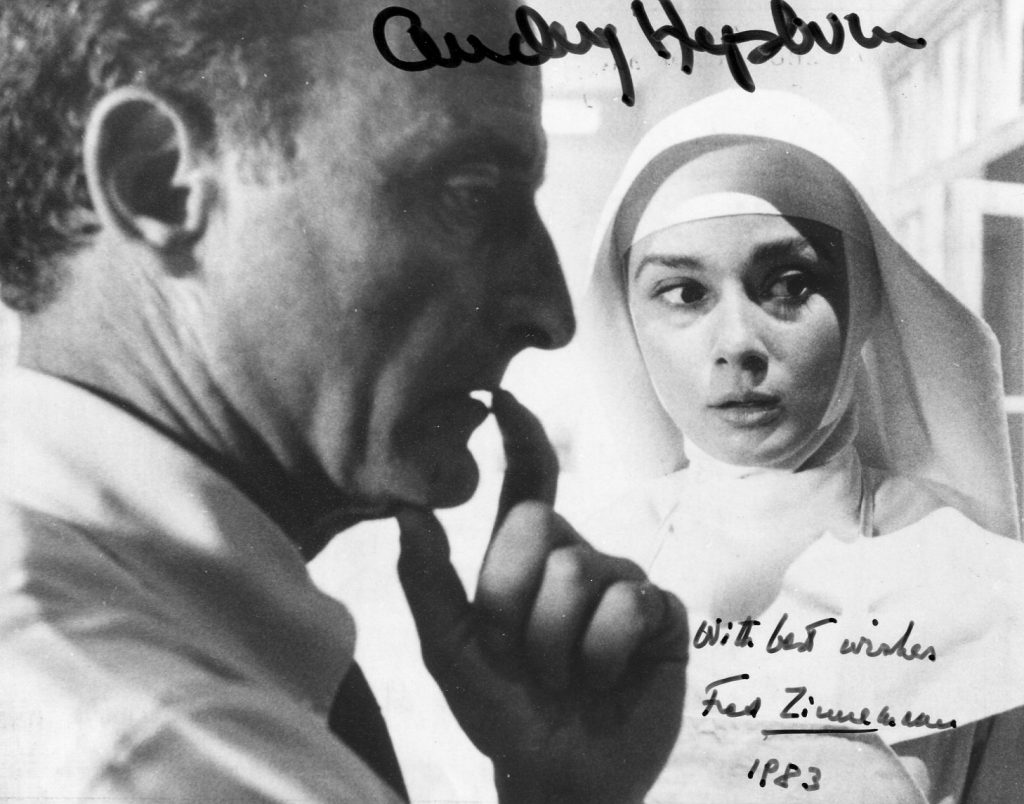

At the same time Hepburn accepted another difficult subject, with another fine director, The Nun’s Story, for Fred Zinnemann. Kathryn Hulme’s novel was also based on fact, about a novice who finds, in the end, that she doesn’t have enough faith to continue. The film remains Hollywood’s best attempt at playing Church, both because it regards it with respect and not piety, yet at the same time allowing us to make our own decisions about the dottiness of the convent system. She held her own against the formidable opposition of Edith Evans and Peggy Ashcroft, both playing Mothers Superior with closed minds – and that was partly because the gentle Zinnemann was nevertheless able to blend their different acting styles, and partly because of Hepburn’s innate instinct for what the camera would allow her to do. Despite her voice mannerisms, here at a minimum, Hepburn was the one star of her generation to suggest intelligence and dignity – which is to say qualities which people, as opposed to actresses, have. Grace, beauty and the sine qua non of stardom made her as rewarding to watch as Garbo, and she can’t disguise them in playing this ordinary girl; but she also has gravity.

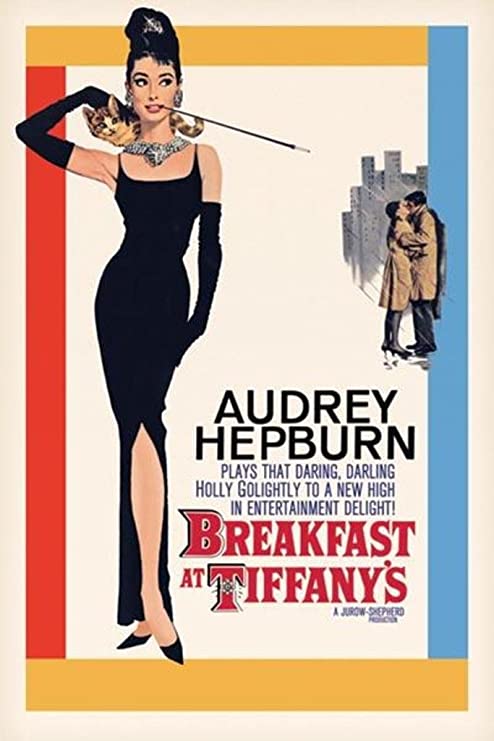

She was touching as Burt Lancaster’s half-breed sister in John Huston’s huge, vasty western The Unforgiven (1960), but Blake Edwards allowed the latent artifice of her screen persona to surface as Holly Golightly in his film of Truman Capote’s novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961). Capote described the result as ‘a mawkish Valentine to Audrey Hepburn’ and George Axelrod, who wrote the screenplay, criticised her for refusing to convey the fact that Holly was a tramp with no morals or principles. No one else seemed to mind.

She had committed herself to the film only after Marilyn Monroe had turned it down, and when there was an impasse with Alfred Hitchcock over No Bail for the Judge. He was desperate to work with her and had spent dollars 200,000 in preparation, when she had second thoughts about a scene in which she was dragged into a London park to be raped. Furious, Hitchcock abandoned the picture rather than go ahead with another actress.

Hepburn was a controversial choice to play Eliza in My Fair Lady (1964). Warners had paid a record sum of dollars 5.5m for the screen rights to the Lerner and Loewe musical version of Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion. Everyone agreed that its extraordinary success was due to the starring trio of Rex Harrison, Julie Andrews and Stanley Holloway. The last of these was the most expendable, but Jack Warner decided to go with Holloway when James Cagney wisely declined to come out of retirement to play Doolittle. No leading star was prepared to risk a comparison with Harrison’s definitive Higgins (‘Not only will I not play it,’ said Cary Grant, ‘I won’t even go and see it if you don’t put Rex Harrison in it’) which meant Andrews had to be replaced by a solid box-office attraction.

Warners had recently released The Music Man with its Broadway star Robert Preston, but the film’s reception was so spotty that they had not opened it in territories where he was an unknown quality. The irony of the My Fair Lady situation was that, as filming was under way, word was coming from the Disney studio that Andrews was sensational in Mary Poppins. She got an Oscar for it; Harrison got one for My Fair Lady, presented by Hepburn, and was thus photographed with his two Elizas. That Hepburn’s singing voice was dubbed did not help her performance (her non-singing voice had done charmingly by the songs in Funny Face), but she brought a street-wise cunning to the role that Andrews lacked. This may not have been what Shaw intended, but George Cukor, who directed, observed that at the end of the film Hepburn fitted Shaw’s own description of Eliza as ‘dangerously beautiful’.

She made only two more successful films: Donen’s Two for the Road (1967), with Albert Finney, a study of a disintegrating marriage written by Frederic Raphael, and Terence Young’s Wait Until Dark (1967), a thriller about a blind girl terrorised by some thugs because they thought there were some drugs stashed away in her apartment. Mention should be made of two other movies, because they were directed by Wyler: How to Steal a Million (1966), a comedy with Peter O’Toole, and The Children’s Hour (1962), a remake of his own These Three. The original Broadway play hinged on a lie told by a child, that two of her teachers have an unnatural affection for each other. The censor would not permit that in 1936, so the plot of the film depended on the child accusing one teacher of filching the other’s fiance. Wyler’s decision to remake the picture was to restore the lesbian element, but the result was flat, despite the fact that Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine were infinitely better actresses than Miriam Hopkins and Merle Oberon, the stars of the 1936 version.

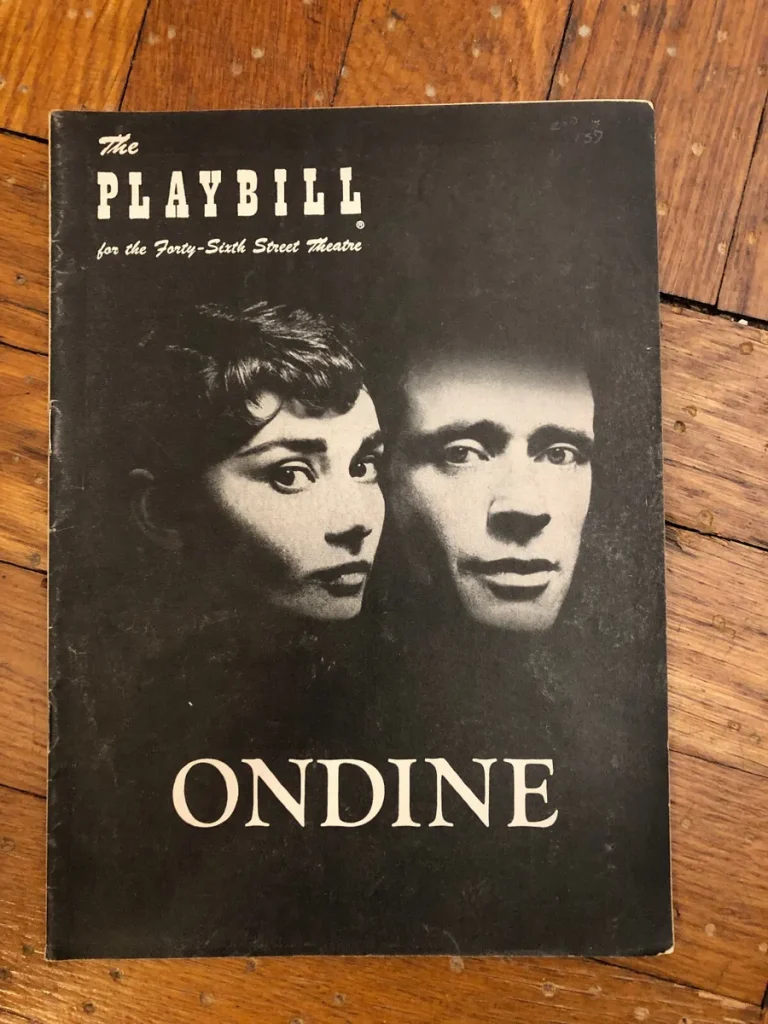

At the height of her career Hepburn made only one out-and-out stinker, Green Mansions, with Anthony Perkins. It may be that WH Hudson’s novel about Rima the Bird Girl is unfilmable (MGM had started shooting one a few years earlier before giving up), but matters here were made worse by the stodgy direction by Mel Ferrer, at that time married to Hepburn. They had met while appearing in Giraudoux’s Ondine in New York in 1954, and he accompanied her to Italy, to play Prince Andrei in War and Peace. When the marriage broke up in 1968 she married an Italian psychiatrist, Andrea Dotti, and announced that a career and marriage were incompatible; so she only intended to film again if she could do so near her homes in Rome and Switzerland.

She came out of retirement five times, and only the first time was worthwhile: to play an ageing Maid Marian to Sean Connery’s Robin in Richard Lester’s Robin and Marian (1976). She was an industrial heiress in Sidney Sheldon’s Bloodline, which was so badly received that she admitted that she had done it because she liked the director, Terence Young. She added that she wanted to go out on a good one – and Peter Bogdanovich’s They All Laughed certainly didn’t provide it. Nobody laughed, including Time-Life, who financed it and dropped it after a few test showings. In 1987 she made a telemovie, Love Among Thieves, and although she herself was praised the press liked neither it nor her co-star, Robert Wagner. In 1989 she played a small role in Always, Steven Spielberg’s remake of A Guy Named Joe, in the role done in the original by Lionel Barrymore as an emissary of the Almighty. She was realistic enough to recognise that there were few meaty roles for actresses of her age – and with Spielberg’s box-office record she hoped to be in a success. She was wrong again.

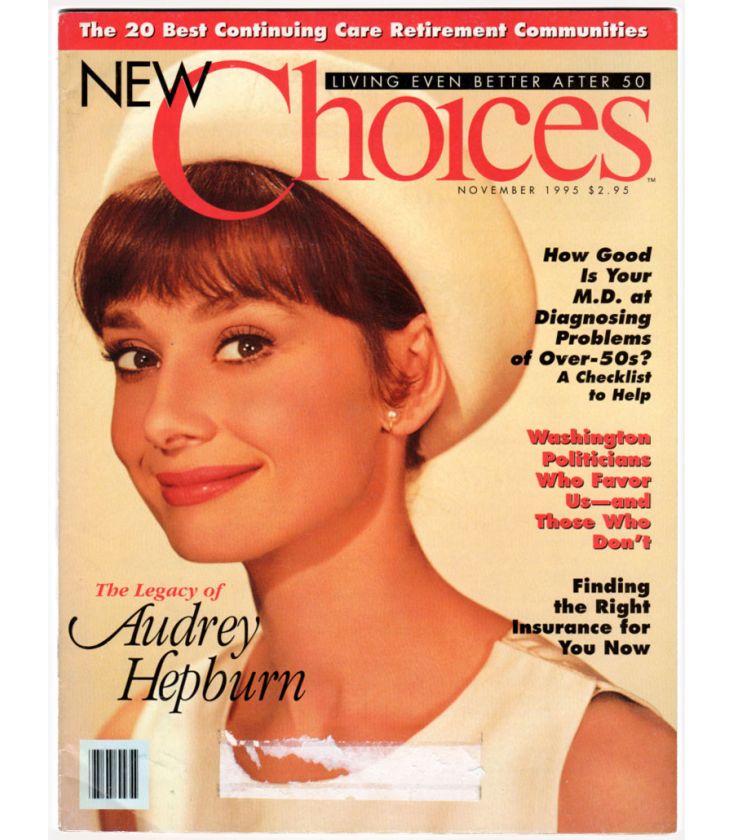

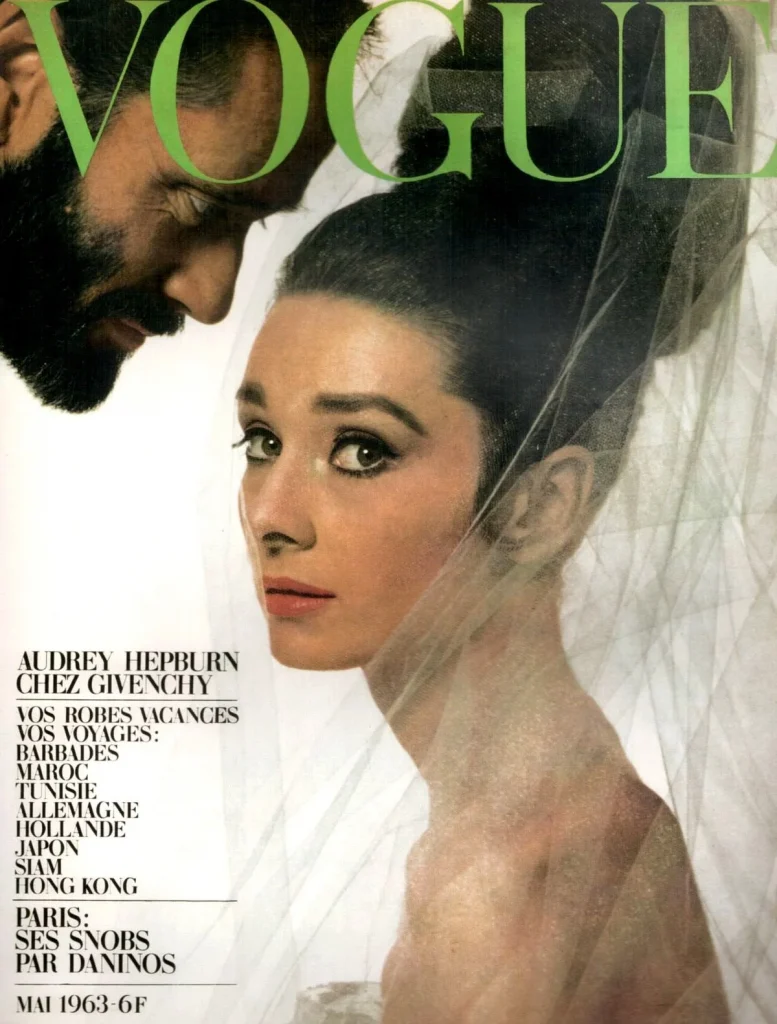

She was by now spending most of her time working voluntarily for Unicef and giving interviews to explain what she was doing and what was needed. Unlike some stars whose identification with charities always looked suspicious, as if they wanted to advance their careers, it was clear that in this case there was no career and she wanted to find something useful to do. She also appeared frequently at movie functions, to be awarded lifetime achievement awards or make the special presentation at the end of the evening. Many people had expected her to age badly, because she had been so scrawny as a young woman. The reverse was the case – for she still possessed in middle age what she had always had: radiance, dignity and, above all, style. This last quality may be summed up by a famous exchange of the 1950s, when her clothes were designed by one of the most celebrated couturiers in Paris. ‘Just think what Givenchy has done for Audrey Hepburn.’ ‘No, just think what Audrey Hepburn has done for Givenchy.’