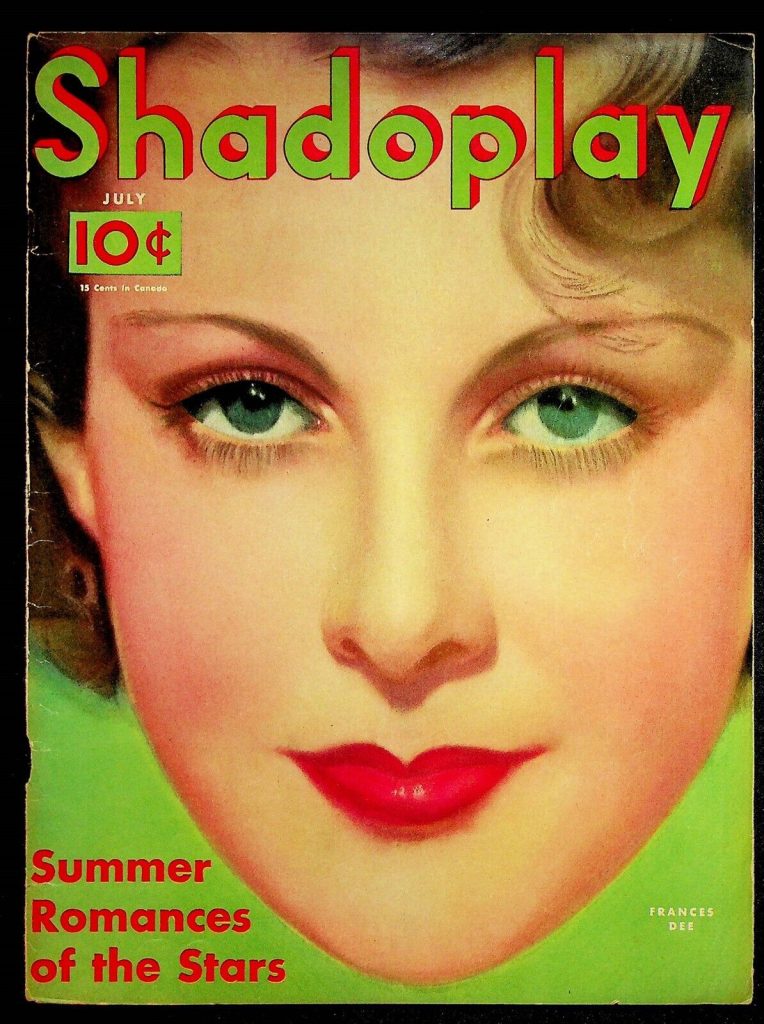

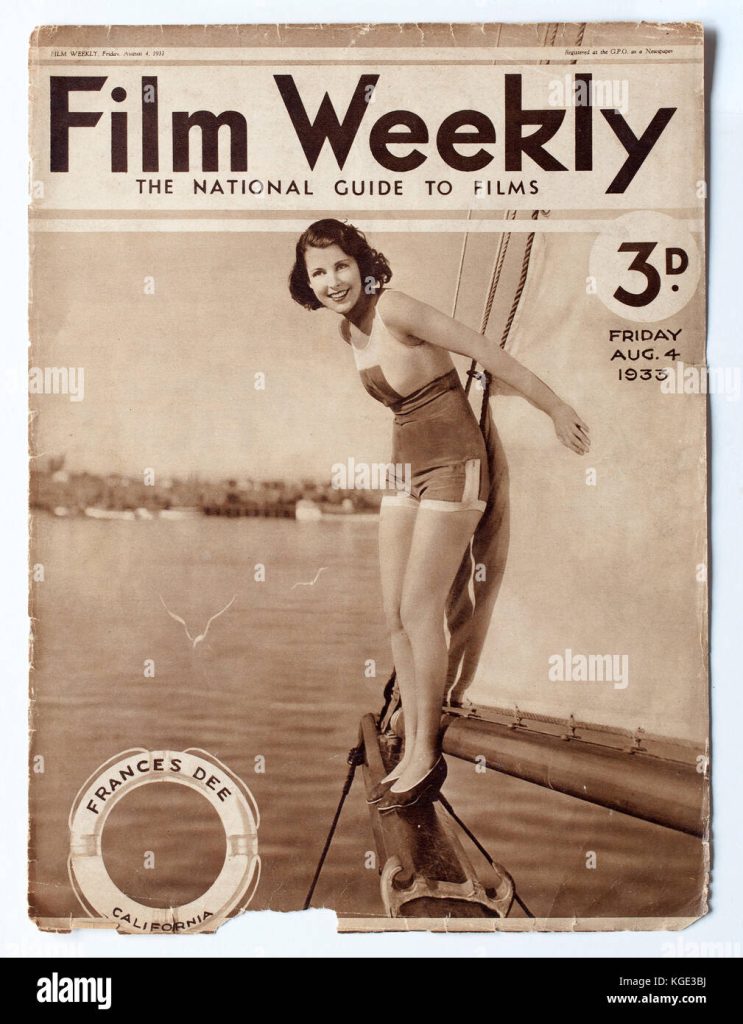

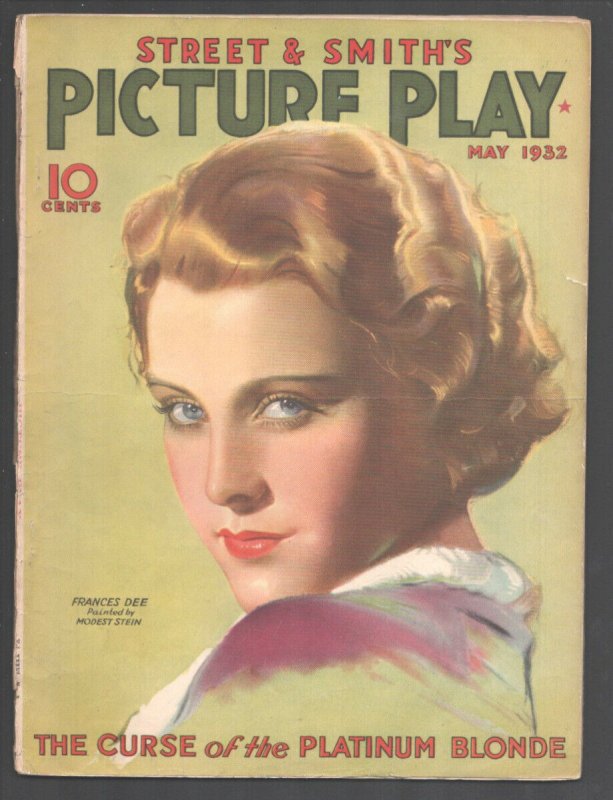

Luminous Frances Dee was a quiet, lovely presence in films in the 1930’s especially. She was born in 1909 in Los Angeles. She made an impact in 1931 in “An American Tragedy”. She went on to make “If I Were King”, “Little Women” and some films with her husband Joel McCrea. She retired from film in the mid 1950’s to concentrate on family life. Frances Dee died in 2004.

Her “Independent” obituary by Tom Vallance:

The critic James Agee said she was “one of the very few women in movies who had a face . . . and always used this translucent face with delicate and exciting talent”. A winsome brunette, whose suitors included the writer/director Joseph Mankiewicz, she was married for 57 years to one of her leading men, Joel McCrea.

The daughter of a civil engineer, she was born Jean Dee in Los Angeles, all reference books say in 1907, though her family aver it was 1909; and was educated at the University of Chicago, where her success in college plays prompted her to journey to Hollywood in the hope that the new sound era had created a need for performers who could handle dialogue:

When I dropped out to go to Hollywood, my father gave me an ultimatum. He told me that I had a year to find something more reliable in the picture business than extra work or else I had to come back.

As a contract player at Paramount, she was an extra in such films asWords and Music (1929), Follow Thru (1930), Manslaughter (1930) and Monte Carlo (1930). Then “almost a year to the day after my father’s ultimatum” she was spotted in the studio commissary by Maurice Chevalier. Lillian Roth, scheduled to play his leading lady inPlayboy of Paris (1930), which was about to start shooting, had been forced to drop out due to commitments in New York. Impressed by Dee’s fresh quality and beauty, Chevalier suggested that she be tested for the role.

Playboy of Paris, a musical remake of Max Linder’s silent comedy Le Petit Café (1920), featured Dee as a young girl who falls in love with a waiter (Chevalier) in her father’s café. When, having inherited a fortune, he samples the nocturnal delights of Paris, she jealously pursues him and gets into a cat-fight with his gold-digging girlfriend. The realisation that she is his true love leads to Chevalier’s rendition of the hit song “My Ideal”.

Dee then starred with Phillips Holmes and Sylvia Sidney in Josef von Sternberg’s An American Tragedy (1931), based on Theodore Dreiser’s novel. The story of a young social climber who murders his pregnant girlfriend when he falls in love with the socialite daughter of his employer, it proved too sordid for popular acceptance (and was banned in Britain), but Dee touchingly conveyed her hopeless love in the role of the socialite later played by Elizabeth Taylor in George Stevens’s 1951 version of the same story, A Place in the Sun.

Joseph Mankiewicz was one of the writers of June Moon (1931), adapted from the Broadway comedy by Ring Lardner and George S. Kaufman, in which Dee was the supportive girl-friend of a small-town simpleton (Jack Oakie) who travels to New York with aspirations to be a song lyricist. Mankiewicz began a romance with Dee, who also starred in This Reckless Age (1932), scripted by him, as the spoiled flapper daughter of self-sacrificing parents.

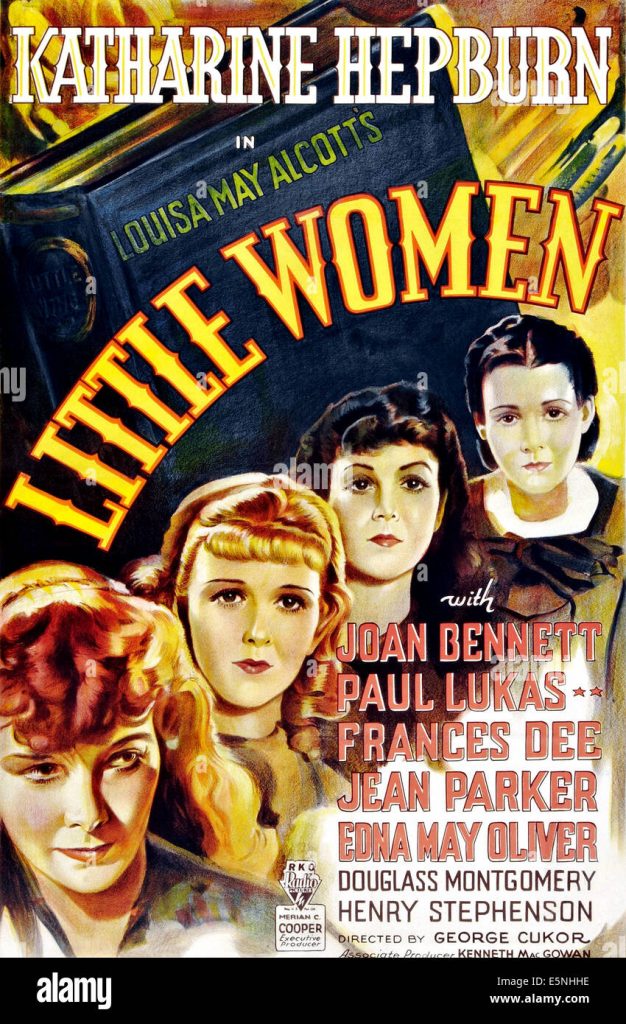

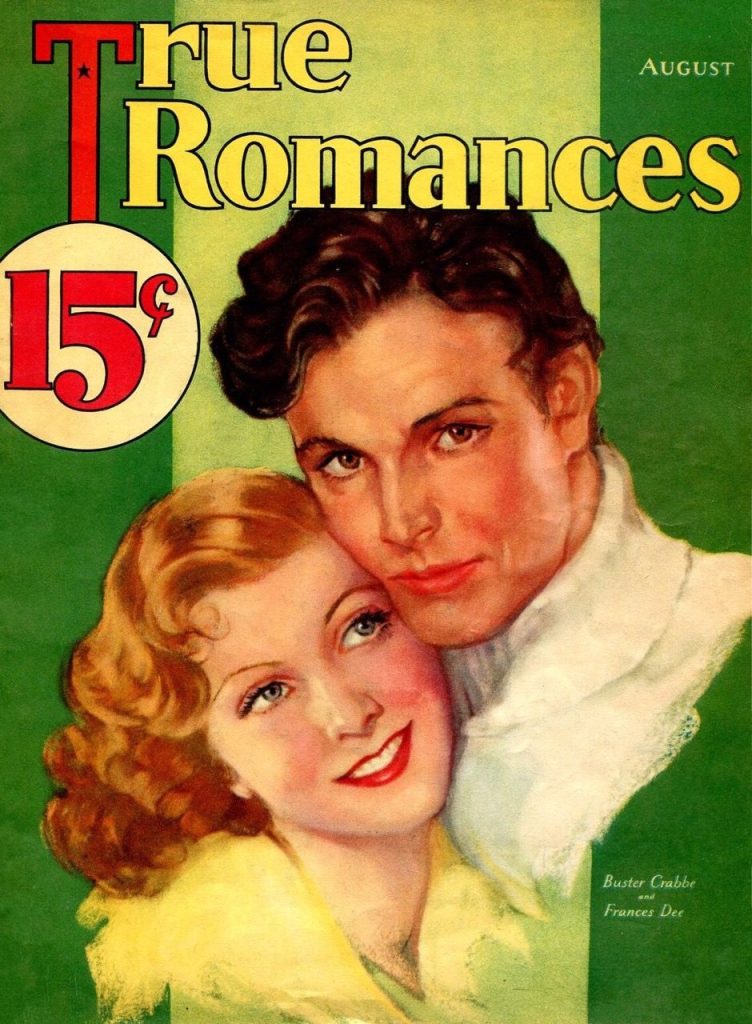

Making five or six films a year at this time, she starred in such vehicles as William Wellman’s Love is a Racket (1932), as a flighty actress loved by a reporter (Douglas Fairbanks Jnr), the omnibus film If I Had a Million (1932), as the wife of a condemned man ironically unable to save himself from the electric chair despite receiving a million dollars, King of the Jungle (1933), in which she falls in love with, and teaches English to, a primitive man (Buster Crabbe) raised by lions in Africa, and George Cukor’s version of Little Women (1933), in which she was sensible Meg to Katharine Hepburn’s Jo, Joan Bennett’s Amy and Jean Parker’s Beth.

Cukor later wanted Dee to play Melanie in Gone With the Wind, but the producer David O. Selznick overruled him, allegedly because he considered her too beautiful and liable to overshadow his Scarlett (Vivien Leigh).

One of Dee’s more notable roles was in a gangster movie, Rowland Brown’s Blood Money (1933), that was a lost film for nearly 40 years before resurfacing to be hailed as a 66-minute gem. Cast against type, Dee played a thrill-seeking rich girl, described by the actress herself as “a masochistic nymphomaniacal kleptomaniac”.

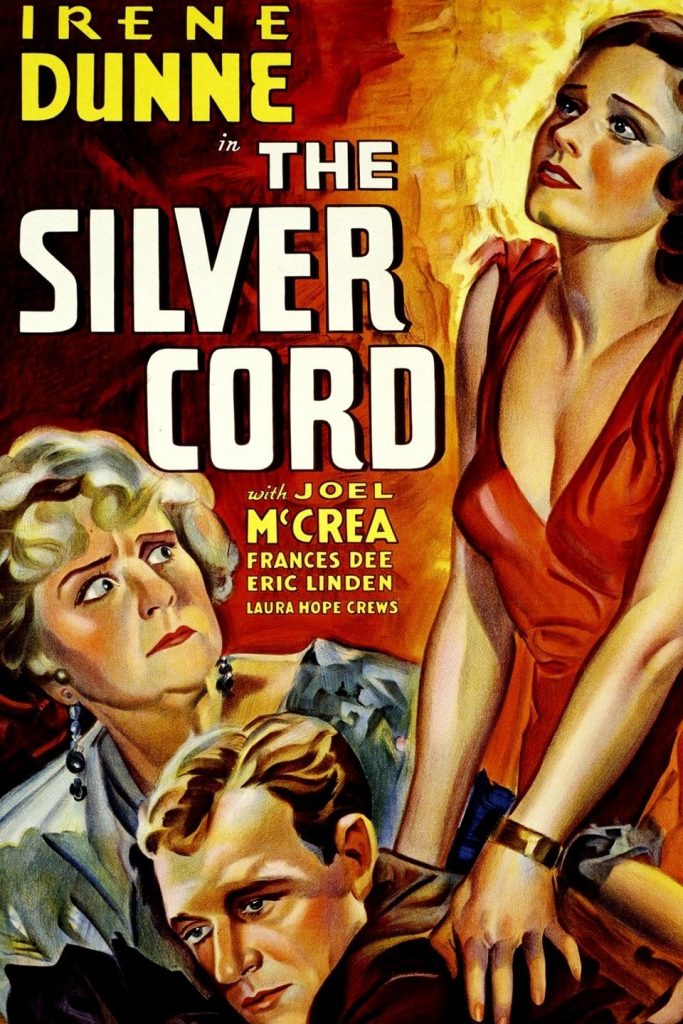

She was then fatefully cast opposite Joel McCrea in an adaptation of the Broadway drama of possessive motherhood, The Silver Cord(1933). Directed by John Cromwell, the gripping tale featured Laura Hope Crews as the tenacious mother with two sons. A married one (McCrea) has a wife (Irene Dunne) who is strong enough to wrench him from his mother’s machinations (including a fake heart attack). The younger son (Eric Linden) is more susceptible to his mother’s tricks, and Dee was extremely touching as his fiancée who finds herself powerless in the struggle and is ultimately abandoned.

Before she started the film, Dee had been enjoying a long-term affair with Mankiewicz, and the couple had planned a summer wedding with a honeymoon tour of New England already mapped out. When Mankiewicz learned that Dee had become engaged to McCrea he was hospitalised with a partial nervous breakdown. Later he claimed that Dee was “the love of my life”, and friends said that the incident was to trigger the pattern that the director later followed of making sure that he was the first to end relationships (as he did with Judy Garland, Linda Darnell and others).

David O. Selznick stated that Dee told him McCrea had made her realise that her attraction to Mankiewicz was purely physical, while McCrea appealed to her intellectually. Married in October 1933, the couple settled on McCrea’s ranch in Ventura County, California. Their first of three sons, Jody (later to become an actor), was born the following year.

Dee’s other films included the lively Headline Shooter (1933), in which she was the girlfriend of an ambitious newspaper photographer, and John Cromwell’s Of Human Bondage (1934), in which she played the girl who finally wins Leslie Howard after his infatuation with a destructive waitress (Bette Davis) ends. She was top-billed in Finishing School (1934) as an unhappy rich girl, but the film was stolen by Ginger Rogers as the school’s prime rebel.

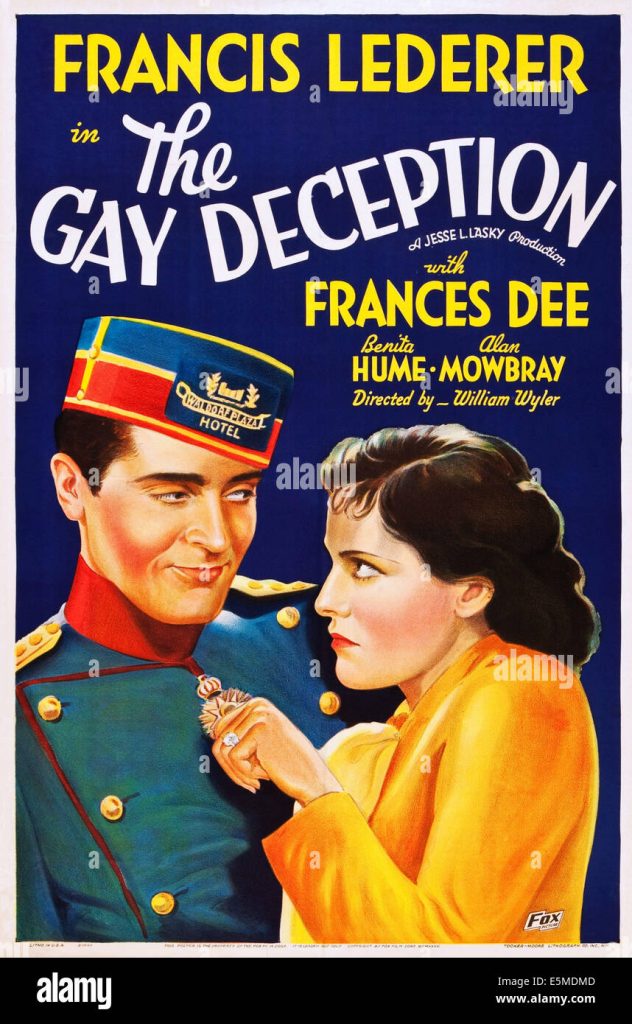

Rouben Mamoulian’s Becky Sharp (1936), based on Thackeray’sVanity Fair, was the first feature film in three-strip Technicolor. Miriam Hopkins played the eponymous gold-digger, with Dee as her friend Amelia Sedle. She had one of her most rewarding roles in William Wyler’s comedy The Gay Deception (1936), in which she played an office worker who wins a modest fortune in a lottery and splurges on a suite in a lavish New York hotel where she meets a prince (Francis Lederer) posing as a bellboy. She would always citeThe Gay Deception as her favourite film.

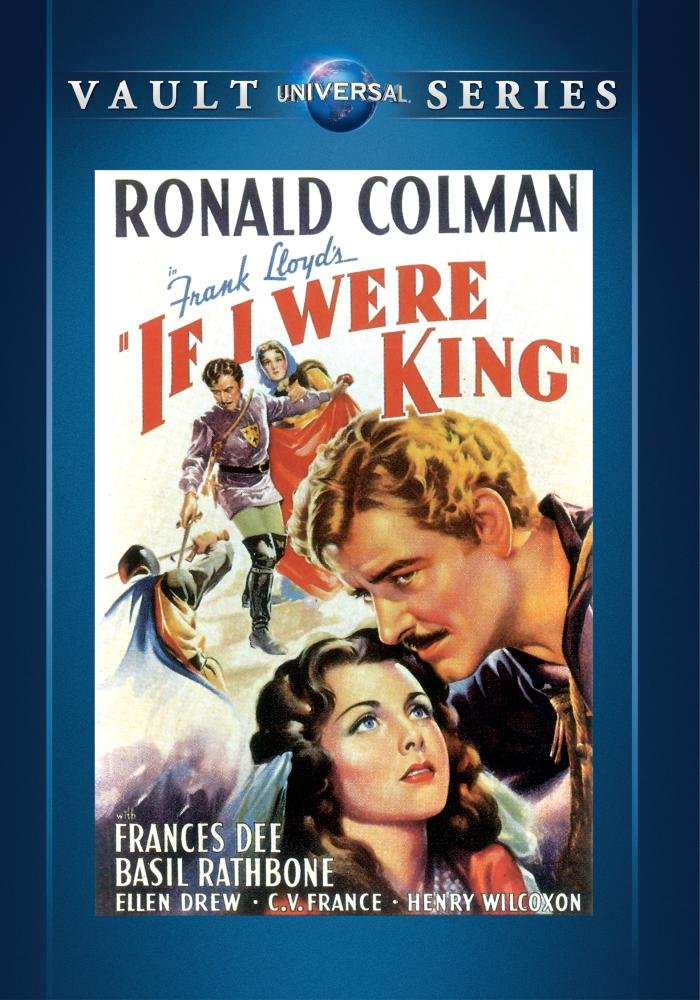

In Henry Hathaway’s popular seafaring tale Souls at Sea (1937), she starred alongside Gary Cooper and George Raft, and she co-starred with McCrea again in Frank Lloyd’s Wells Fargo (1937). In this ambitious history of the express company, McCrea played a loyal employee whose marriage breaks up when he and his wife (Dee) find themselves sympathising with opposite sides during the Civil War. In Lloyd’s If I Were King (1937), a romantic swashbuckler set in 15th-century France, Dee was the Queen’s lady-in-waiting who is wooed by the poet François Villon (Ronald Colman).

Around this time Dee, who now had two sons, decided to limit her films in order to give more time to her family. McCrea said, “There are four of us now. Frances has deliberately cut and maybe weakened her career.”

She worked with the director John Cromwell again on the anti-Nazi movie So Ends Our Night (1941) as the wife of an Austrian refugee (Fredric March). The critic Pauline Kael described a close-up of Dee’s face, as she sees but cannot speak to her fugitive husband, as comparable to that of Garbo at the end of Queen Christina.

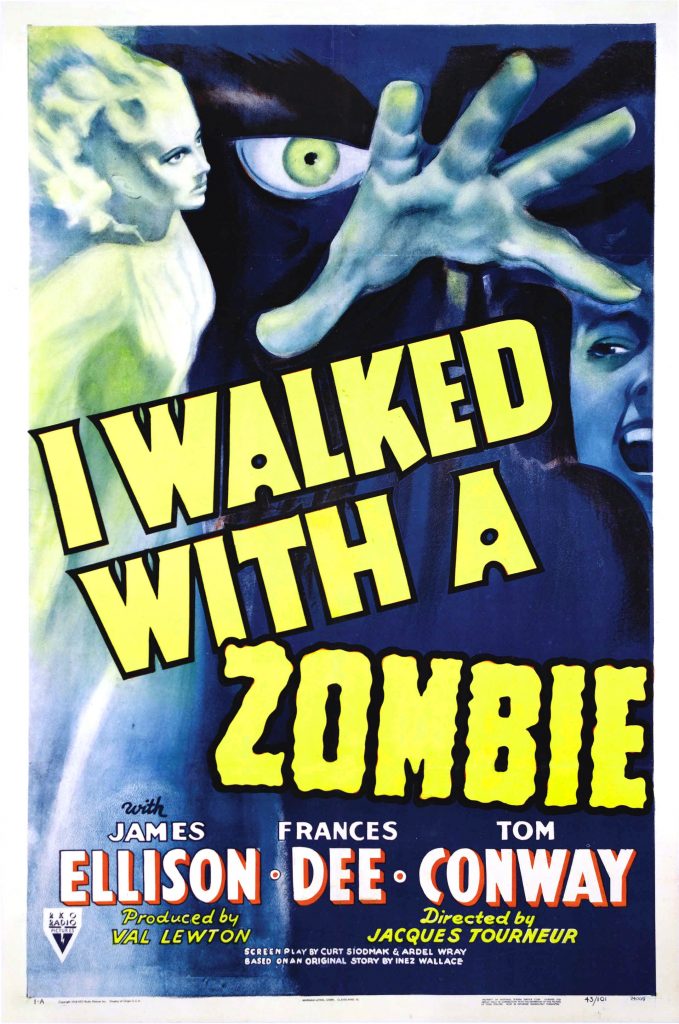

I Walked With a Zombie (1943) was a B movie, but is regarded now as highly as any of Dee’s major films. Produced by Val Lewton and directed by Jacques Tourneur, it was a chillingly atmospheric tale of a nurse (Dee) who goes to the West Indies to look after a catatonic patient and encounters rampant voodooism. In the film’s most celebrated sequence, Dee takes her mute patient on a prolonged and haunting walk through the cane fields, punctuated with native chants and shadowy low-key photography, to attend a voodoo ceremony. “People think of I Walked With a Zombie as a scary film”, said Dee,

and it is. But it was also scary to be in it. When I first read the script I couldn’t imagine anyone ever liking the movie. Yet, thanks to Lewton and Tourneur, it turned out very well.

In 1946 Dee made her Broadway début in the drama The Secret Room, directed by Moss Hart, but it ran for only 21 performances. On screen she was one of the women exploited by the unscrupulous hero (George Sanders) in The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (1947), and she starred with McCrea for the final time in Four Faces West(1948), an unusually gentle western in which not a shot is fired.

She was a schoolteacher who comforts Barry Sullivan when he separates from his wife (Bette Davis) in Payment on Demand (1950), and had her last role in the family film Gypsy Colt (1954), a loose adaptation of Lassie, Come Home with the homesick animal a horse instead of a dog.

In 1955, the year her third son was born, she announced her retirement, and the McCreas were considered one of the happiest families in Hollywood until 1966, when they announced the startling news that they were separating. Dee proclaimed that she found ranch life unfulfilling, and McCrea actually filed for divorce, but the couple reconciled and their union endured until McCrea’s death in 1990.

Over the years, McCrea expanded his ranch and bought up tracts of land in California, Nevada and New Mexico that made the couple one of the wealthiest in California, but after his death some disastrous speculation reduced the fortune considerably.

In recent years, Dee occasionally attended film conventions and tributes, such as a month-long festival of her films held in Hawthorne, New Jersey, in 1999. She had also been collaborating on a biography with the writer Andy Wentink.

Tom Vallance’s “Independent” obituary can also be accessed here.