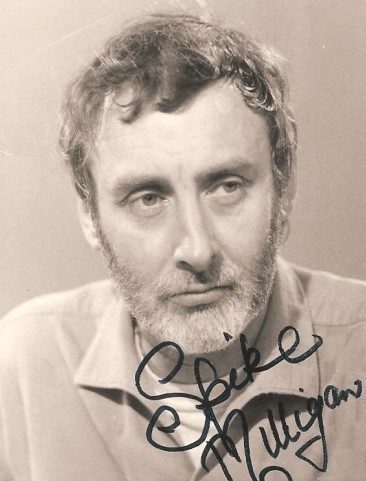

The great comedian and write Spike Milligan was born in India in 1918. The majority of his career was spent in British radio, television and film. He was part of the famous radio quartet “The Goons” which included Michael Bentine, Peter Sellers and Harry Secombe. His films include “The Bed-sitting Room”, “Adolf Hitler, My Part in His Downfall” and “Digby, the Biggest Dog in the World”. Spike Milligan was an Irish citizen. He died in 2002.

“Guardian” obituary by Stephen Dixon:

Spike Milligan, who has died aged 83 of kidney failure, was once talking about Eccles, his favourite Goon Show character. “Eccles represents the permanency of man, his ability to go through anything and survive. They are trying to get off a ship on the Amazon and lower a boat. When they get to the shore Eccles is already there.”‘How did you get ashore?'”‘Ho hum, I came across on that log.’

“‘Log… that’s an alligator!’

“‘Ooh. I wondered why I kept getting shorter.'”

That brief exchange, recognisable instantly as something only Milligan could have written, does tell us something about this troubled, gifted man, with his unique mind and puzzled pity for humanity.

Jimmy Grafton, who co-wrote many of the early shows, maintained that Eccles was the nearest thing to Milligan’s own id – a very simple, uncomplicated creature who doesn’t want to be burdened with any responsibility and just wants to be happy and enjoy himself. Grafton added: “Spike achieved a reputation for eccentricity and has become, by his own choice, a sort of court jester. You begin to wonder to what extent in some circumstances the eccentricity is involuntary and to what extent it is deliberate. He can always get out of trouble by going a little mad.”

Milligan never achieved Eccles’s simple dream of happiness, and comedy is richer for his failure. He lived his life at the end of his mind’s tether and was always a man of seemingly irreconcilable contradictions: an anarchist with a passion for conservation, a vulnerable and acutely sensitive exhibitionist, a sophisticated person who preferred to retain a vision of childlike purity.

He was often distinctly unsettling, both offstage and as a writer/performer. The writer and jazz singer George Melly, while admitting that Milligan was not the sunniest person all the time, added that his was “the greatest mind in what is loosely called comedy”.

George Orwell’s assertion that “whatever is funny is subversive” was never truer than in the case of Milligan. He didn’t invent surrealistic radio comedy – nor did he ever claim to – but he opened up the medium with his uncluttered anarchic vision, and his influence since the early 1950s has been vast. It took its toll: “I was trying to shake the BBC out of its apathy. I had to fight like mad and people didn’t like me for it. I had to bang and rage and crash. I got it right in the end, and it paid off, but it drove me mad in the process… I’m unbalanced. I’m not a normal person, and that’s a very hard thing to have placed upon you in life.”

Milligan was born in Poona, India. He was the son of an Irish captain in the Royal Artillery, and Irishness, represented by his contempt for authority and his free-wheeling humour – one thinks of the novelist Flann O’Brien – always ran through his work. His father was a frustrated entertainer who did impressions of GH Elliott, the “Chocolate-Coloured Coon” at camp concerts, but never had the confidence to turn professional, and Milligan appeared at such concerts from an early age.

“I wasn’t consciously aware of it,” he said, “but I had had enough of the British empire. The Goons gave me a chance to knock people my father and I had to call ‘Sir’. Colonels. Chaps like Gritpipe-Thynne with educated voices who were really bloody scoundrels.”

Milligan was educated at the Convent of Jesus and Mary, Poona, and, after his father was posted to Rangoon in 1929, at the Brothers de La Salle; the family stayed in Burma until 1933, when they returned to England to what Milligan described as a fairly impoverished life and where his education continued at the South East London Polytechnic in Lewisham. He worked in a nuts and bolts factory, but had already decided to become an entertainer, and learned to play the ukulele, guitar and trumpet. At one point he won a Bing Crosby crooning competition at the Lewisham Hippodrome.

When the war broke out he joined his father’s old regiment and served in north Africa, where he first met Harry Secombe. He began to organise music and comedy shows for the armed forces entertainment organisation Ensa with Secombe and others, and was wounded in Italy. His war experiences later formed the basis for a number of bestsellers, including Adolf Hitler, My Part In His Downfall (1971), Monty, My Part In His Victory (1976) and Mussolini, His Part In My Downfall (1978).

Back in civvies in 1946, he formed a trio and started the weary round of agents and audition rooms. The act failed to generate any enthusiasm, and when it broke up Milligan “sort of wandered around”. It was during these wanderings that he renewed his friendship with Secombe, who had been struggling along as a comic at the Windmill Theatre in London’s West End which, in a pre-strip club era, provided static nude tableaux. He also made the acquaintance of another young hopeful, Peter Sellers, and the wild-haired and equally anarchic Michael Bentine.

All gravitated to Jimmy Grafton’s pub in Westminster, where they would do turns in the back room to entertain each other. And it was there that the seeds of the Goon Show were sown.

Grafton was writing jokes for the radio comedian Derek Roy and, impressed by Milligan’s unique view of the world, asked him to co-write some material. In this way Milligan wrote for several top comics of the day – Bill Kerr, Alfred Marks and even Frankie Howerd. He also wrote for Secombe and Sellers, who had started to become established, in a modest way, as radio performers. Sellers had the best contacts and first put the idea for the Goon Show to the BBC (“Goon” came from a strange being in the Popeye cartoons which Milligan loved).

The corporation was lukewarm, but agreed to give the show – starring Sellers, Milligan, Bentine and Secombe – a trial run under the title Crazy People. Thus it began in May 1951, swiftly changing its title and losing Bentine, whose surreal style clashed with Milligan’s. It ran, with 26 shows a year, for nine years. It toured the variety theatres as a stage show in the early 1950s, and it was on this tour that Milligan’s emotional imbalance began to assert itself. In Coventry his solo spot went badly and he strode to the footlights and raged at the audience: “You hate me, don’t you?”

Receiving an affirmative, he threw his trumpet to the stage and stamped on it, and when this was greeted with appreciative applause, left the stage and locked himself in his dressing room. Knowing about their friend’s mental instability, Secombe and Sellers broke down the door, fearing that he had tried to kill himself. He hadn’t, but it was an omen of unhappy times to come.

Milligan, with or without Grafton or Larry Stephens, wrote all the shows, with Eric Sykes drafted in to help on occasion. Although the show could hardly have existed without Milligan’s participation, his difficult behaviour kept him at constant loggerheads with the BBC. However, it was when the programmes ended – at Milligan’s instigation – in 1960 that his personal demons started to dominate his private and professional life. “When the Goons broke up I was out of work,” he said. “My marriage ended because I’d had a terrible nervous breakdown – two, three, four, five nervous breakdowns, one after other. The Goon Show did it. That’s why they were so good.”

Because of the “difficult” label, he almost had to beg for work, and the first to respond was the actor/manager Bernard Miles, who asked him to play Ben Gunn in Treasure Island at the Mermaid Theatre on the edge of the City of London. It was during its successful run that Milligan and John Antrobus wrote the bleak comedy The Bed-Sitting Room, which was set in the aftermath of the third world war. It, too, opened at the Mermaid, in 1963, with Milligan appearing as a sort of disruptive “chorus”, and then went to the Duke of York’s Theatre and the Comedy Theatre. In 1970 the play was made into a film.

His next piece, Oblomov, was just as successful, opening at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, in 1964. It was based on the Russian classic by Ivan Goncharov, and gave Milligan the opportunity to play most of the title role in bed. Unsure of his material, on the opening night he improvised a great deal, treating the audience as part of the plot almost, and he continued in this diverting manner for the rest of the run, and on tour as Son Of Oblomo

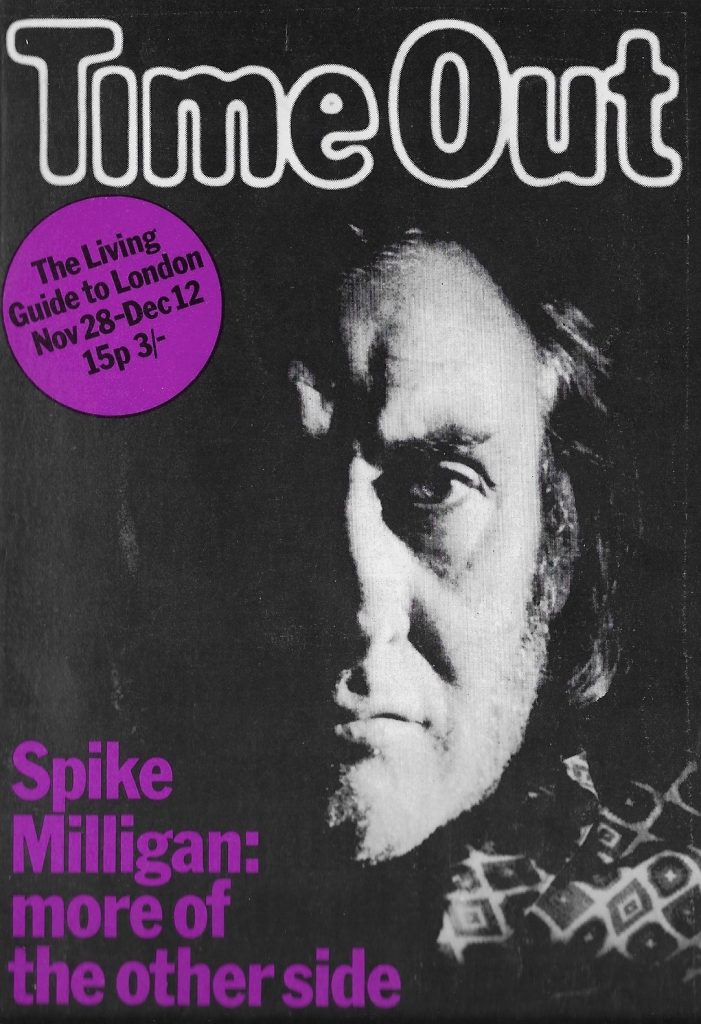

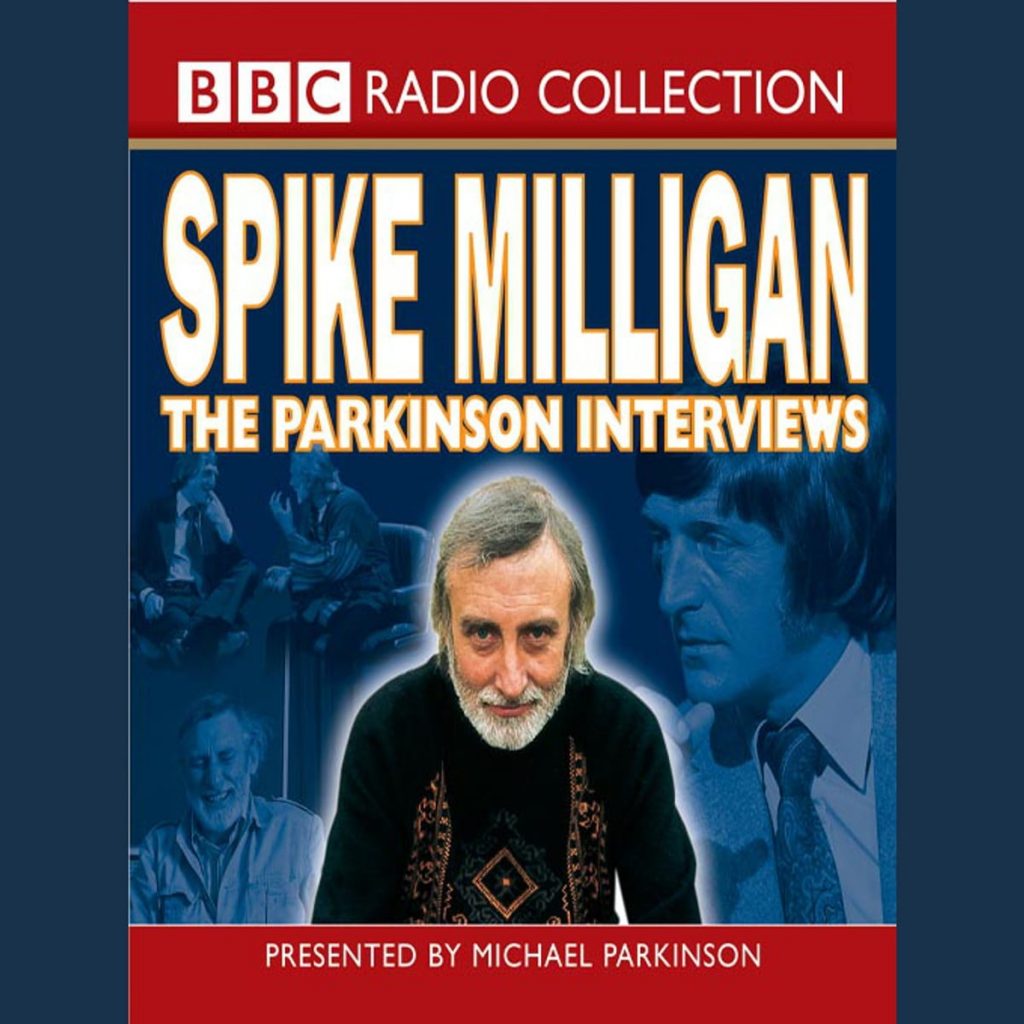

In the late 1960s he did a number of television series, notably the World Of Beachcomber and Q5. He also became a favourite on TV chat shows, although it was with some trepidation that the host – be he Michael Parkinson, Eamonn Andrews or Terry Wogan – would introduce him. Milligan rarely had much of an inkling of what he was going to do, even at far more formal, scripted occasions. “I turn up on the day,” he said. “They point me at the audience and I do it.”

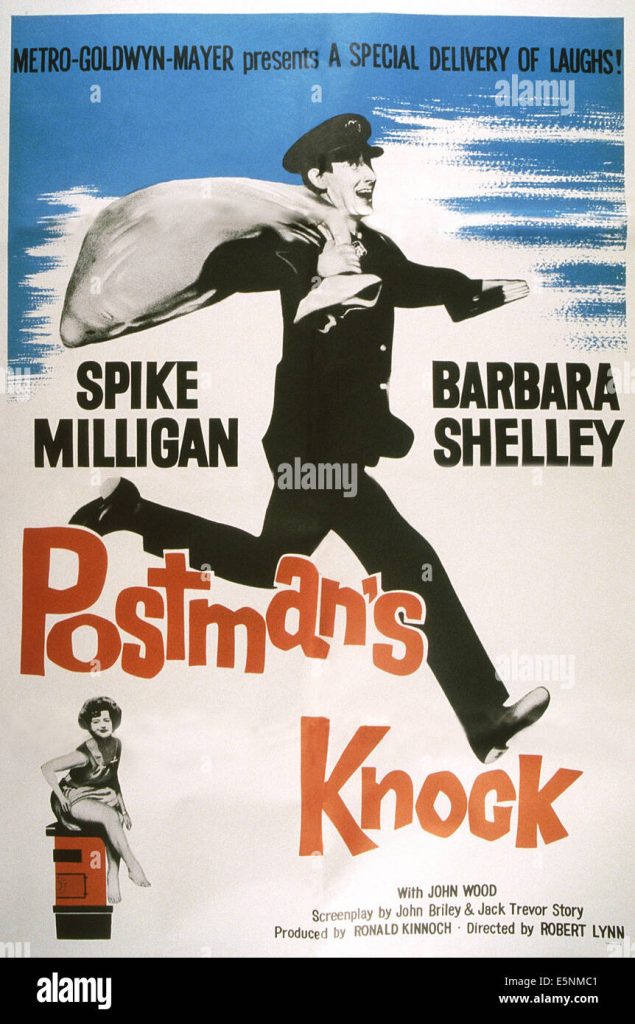

He also turned his attention to the cinema. His films included The Magic Christian (1971), The Devils (1971), The Three Musketeers (1973), The Last Remake of Beau Geste (1977) and Monty Python’s Life Of Brian (1978). On the the big screen there was not marked success, for it was impossible to get near the essence of Milligan in short, carefully rehearsed takes.

He worked harder than almost any entertainer one can think of, but seemed to have an imperfect grasp of what was good and what was dashed-off self-indulgence in his prolific output – a Private Eye cartoon in 1984 had a bookshop with a sign in the window: “Spike Milligan will be here to write his latest book at three o’ clock.” Novels, memoirs, verse – words gushed from him in a torrent.

He seemed to mellow in later years, but there was always a hint of the dangerous spark that had brought him to the brink of despair so many times and lit beacons of laughter to cleanse us all. In 2000, to a clutch of awards was added an honorary knighthood. It was honorary because – and earlier the cause of considerable furore – his father’s Irish background meant that he was denied automatic British citizenship and thus the official title.

His first marriage, to June Marlowe, ended in divorce. His second wife, Patricia Ridgeway, died in 1978. He is survived by his third wife, Shelagh Sinclair; they were married in 1983. He leaves two daughters and a son from his first marriage, and a daughter from his second.

· Terence Alan (Spike) Milligan, writer and performer, born April 16 1918; died February 27 2002.ccessed

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.