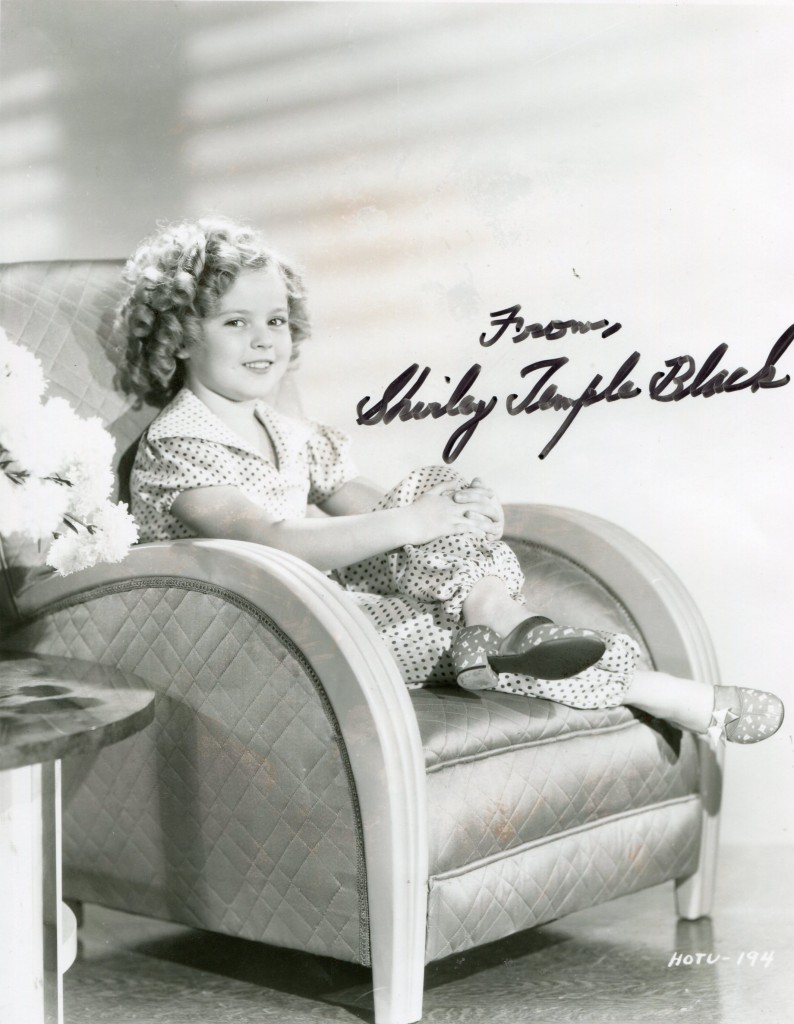

Shirley Temple is regarded as the most popular child actress ever on film. Her films during the Depression in the 1930’s provided light relief to a weary public. Maybe we need her again to-day. She was born in 1928 in Santa Monica, California. Among her best remembered films are “Heidi”, “Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm”, “Little Miss Broaday” and “A Little Princess”. As she matured she film roles became more infrequent although she was very effective in “Since You Went Away” as one of the daughters of Claudette Colbert on the home front. Jennifer Jones was the other. She also starred in John ord’s “Fort Apache” with Henry Fonda. After retiring from film, she entered the world of politics and joined the Republican party. She served as U.S. Ambassador to Ghana from 1974 until 1976 and Ambassador to Czechoslovakia from 1989 till 1992. She died in 2014.

Her obituary in “The Economist”:

THERE had to be a dark side to Shirley Temple’s life. Biographers and interviewers scrabbled around to find it. The adorable dancing, singing, curly-haired moppet, the world’s top-earning star from 1935 to 1938, surely shed tears once the cameras were off. Her little feet surely ached. Perhaps, like the heroine of “Curly Top”, she was marched upstairs to bed afterwards by some thin-lipped harridan, and the lights turned resolutely off.

Not a bit of it. She loved it all, both then and years later, when the cuteness had gone but the dimples remained. Hadn’t her mother pushed her into it? No, just encouraged her, and wrapped her round with affection, including fixing her 56 ringlets every night and gently making her repeat her next day’s lines until sleep crept up on her. Hadn’t she been punished cruelly while making her “Baby Burlesks”, when she was three? Well, she had been sent several times to the punishment box, which was dark and had only a block of ice to sit on. But that taught her discipline so that, by the age of four, she would “always hit the mark”—and, by the age of six, be able to match the great Bill “Bojangles” Robinson tap-for-tap down the grand staircase in “The Little Colonel”.

To some it seemed a stolen childhood, with eight feature films to her name in 1934, her breakthrough year, alone. Not to her, when Twentieth-Century Fox (born out of struggling Fox Studios that year on her glittering name alone) built her a little bungalow on the lot, with a rabbit pen and a swing in a tree. She had a bodyguard and a secretary, who by 1934 had to answer 4,000 fan-letters a week. But whenever she wanted to be a tomboy, she was. In the presidential garden at Hyde Park she hit Eleanor Roosevelt on the rump with her catapult, for which her father spanked her.

The studios were full of friends: Orson Welles, with whom she played croquet, Gary Cooper, who did colouring with her, and the kind camera crews. She loved the strong hands that passed her round like a mascot, and the soft laps on which she was plumped down (J. Edgar Hoover’s being the softest). The miniature costumes thrilled her, especially her sailor outfit in “Captain January”, in which she could sashay and jump even better; as did her miniature Oscar in 1935, the only one ever awarded to somebody so young. Grouchy Graham Greene mocked her as “a complete totsy”, but no one watching her five different expressions while eating a forkful of spinach in “Poor Little Rich Girl” doubted that she could act. She did pathos and fierce determination (jutting out that little chin!), just as well as she did smiles.

Her face was on the Wheaties box. It was also on the special Wheaties blue bowl and pitcher, greeting people at breakfast like a ray of morning sunshine. Advertisers adored her, from General Electric to Lux soap to Packard cars. After “Stand up and Cheer!” in 1934 dolls appeared wearing her polka-dot dress, and after “Bright Eyes” the music for “The Good Ship Lollipop” was on every piano, as well as everyone’s brains: “Where bon-bons play/ On the sunny beach of Peppermint Bay.”

Her parents did not tell her there was a Depression on. They mentioned only good things to her. Franklin Roosevelt declared more than once that “America’s Little Darling” made the country feel better, and that pleased her, because she loved to make people happy. She had no idea why they should be otherwise. Her films were all about the sweet waif bringing grown-ups back together, emptying misers’ pockets and melting frozen hearts. Like the dog star Rin Tin Tin, to whom she gaily compared herself, she was the bounding, unwitting antidote to the bleakness of the times.

A toss of curls

She was as vague about money as any child would, and should, be. Her earnings by 1935 were more than $1,000 (now $17,000) a week—from which she was allowed about $13 a month in pocket money—and by the end of her career had sailed past $3m (now $29m). But when she found out later that her father had taken bad financial advice, and that only $44,000 was left in the trusts, she did not blame him. She remembered the motto about spilt milk, and got on with her life.

Things appeared to dive sharply after 1939, when her teenage face—the darker, straighter hair, the troubled look—failed to be a box-office draw. She missed the lead in “The Wizard of Oz”, too. She shrugged it off; it meant she could go to a proper school for the first time, at Westlake, which was just as exciting as making movies. By 1950 she had stopped making films altogether; well, it was time. She couldn’t do innocence any more, and that was what the world still wanted. Her first husband was a drunk and a disaster, but the marriage brought her “something beautiful”, her daughter Susan. The second marriage, anyway, lasted 55 years. She lost a race for Congress in 1967: but when that door closed another opened, as an ambassador to Ghana and Czechoslovakia. Breast cancer was a low point, but she learned to cope with it, and helped others to cope. “I don’t like to do negatives,” she told Michael Parkinson. “There are always pluses to things.”

In the films, her sparkling eyes and chubby open arms included everyone; one toss of her shiny curls was an invitation to fun. Her trademark was, it turned out, that rare thing in the world, and rarer still in Hollywood: a genuine smile of delight.

“The Economist” can also be accessed online here.