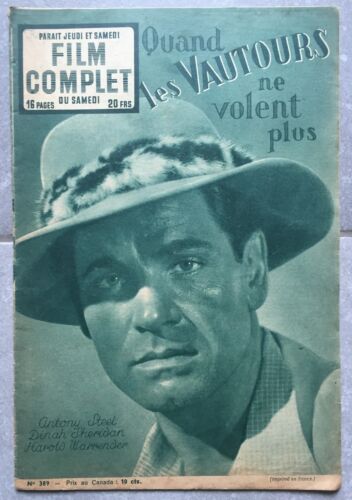

Anthony Steel obituary in “The Guardian” in 2001.

Anthony Steel was born in 1920 in London. He was the son of an Indian army officer and studied at Cambridge. He was a film favourite in Britian in the early 50’s and his films include “The Wooden Horse” in 1950 followed by “The Mudlark”, Malta Story” and “The Sea Shall Not Have Them”. In the mid 50’s he married Anita Ekberg and went to Hollywood, His stay in the U.S. was short and he returned to film making in the UK. He died in 2001 .

His “Guardian” obituary by Dennis Barker:

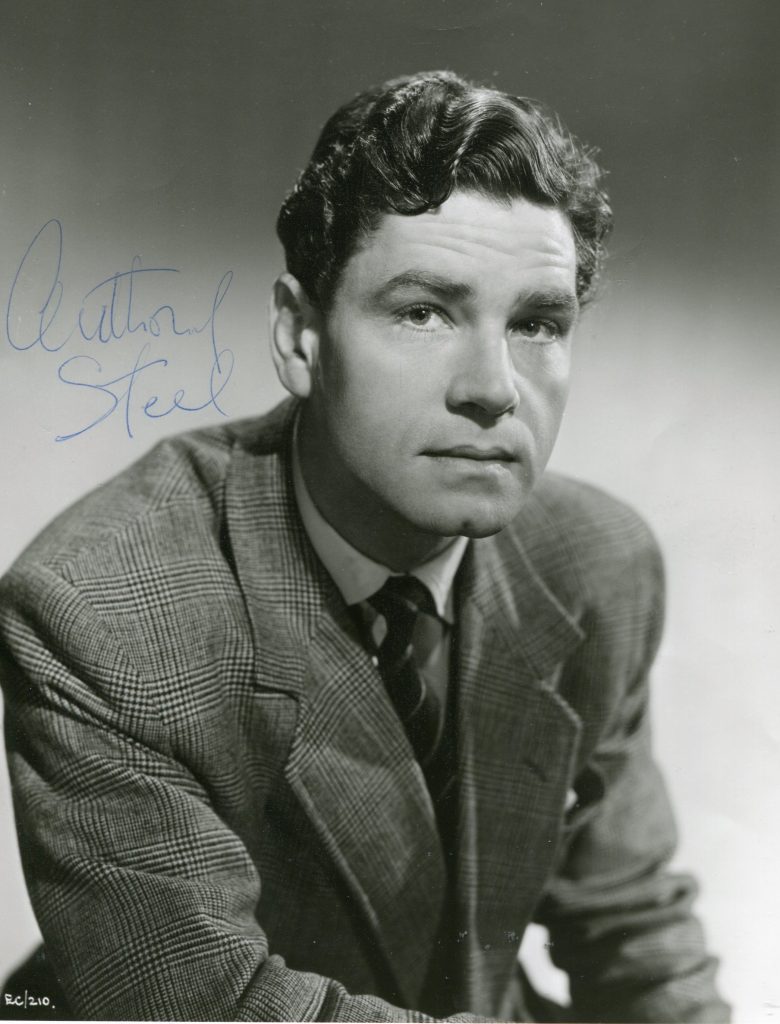

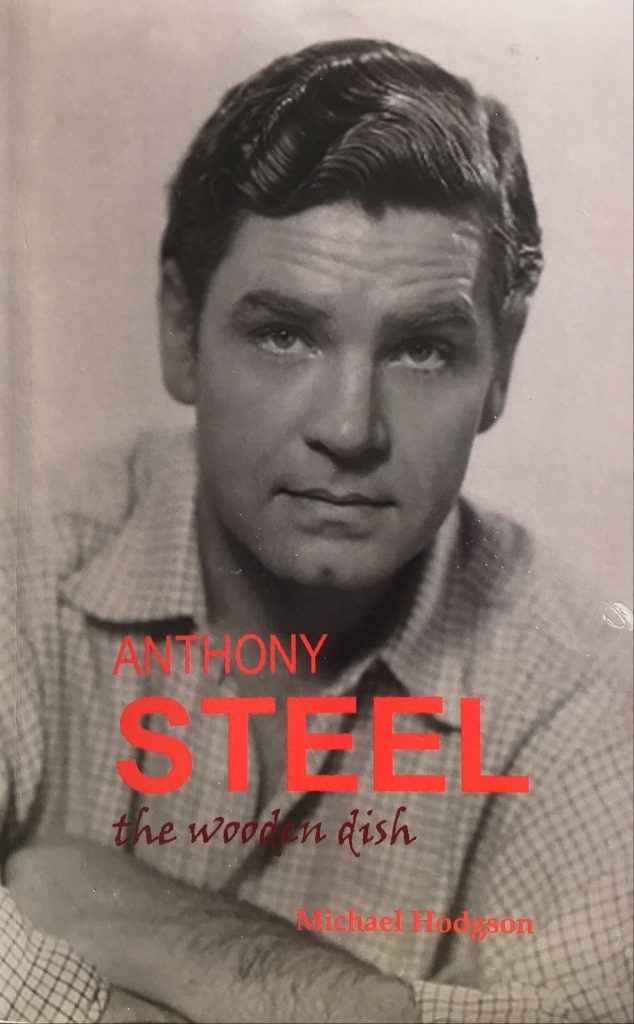

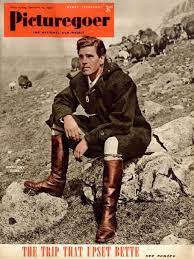

The life of Anthony Steel who, alongside Dirk Bogarde, was the highest-paid star in the great 1950s peak of the British film industry, was a sad story of riches to rags. Steel, who has died aged 80, was the stiff-upper-lipped star of many distinguished British war films, and seen by the Rank Organisation as someone who could be promoted as a heart-throb – the British answer to Gregory Peck and Rock Hudson

But at the height of his fame, Steel – tall, handsome, well-connected, and gentlemanly off the screen as well as on it – suddenly broke his contract with Rank to go in pursuit of the voluptuous Swedish actress Anita Ekberg in Hollywood. He was never forgiven by Sir John Davis, the bull-headed chief of Rank at that time.

His career in Hollywood died in comparison with Ekberg’s, and his marriage to her ended in bitter rows. His subsequent career was patchy, and, after stage tours in the 1980s, the next decade found him living, first in a seedy Earl’s Court hotel, then in sheltered accommodation in a tiny council flat in Northolt, west London, with graffiti on the walls. Almost totally cut off from his past, he would never tell friends where he was, and never contact his agent, David Daly.

When he read of Steel’s plight in a tabloid newspaper in the middle 1990s, Daly had £1,500 due to the actor in television residual payments and other fees, but had no idea where to send it. The newspaper told him the address, and Daly drove there. At first, Steel refused to answer the door bell, which Daly did not find inexplicable in view of the environment, but later he opened a window and recognised his personal friend of 31 years’ standing.

Daly passed Steel £500 in cash, and told him he would find him somewhere better to live, ultimately getting him admitted to Denville Hall, the London home for retired theatrical people, and getting him a role as Dr Steven Hart, the guest lead in the television series The Brokers Man II.

But he was not entirely surprised to find that Steel had lived in the tiny council flat for seven or eight years, and had cut himself off from outside contact: “He was a very private man. He just decided that he would withdraw. He found a place to live and simply went into hiding. In some ways, it was not unlike him; if he decided that things weren’t right, he would withdraw into himself and not contact anybody.”

Such was the downbeat ending. In 1948, when Steel made his first film, Saraband For Dead Lovers, he was hailed as a more polished version of what was then thought of as the beefcake which would beat Hollywood idols at their own game. The following year, Marry Me was hailed as a principal showcase for his presence and, in 1950, when the wartime escape film, The Wooden Horse, appeared, he seemed to be well on his way to becoming an international icon.

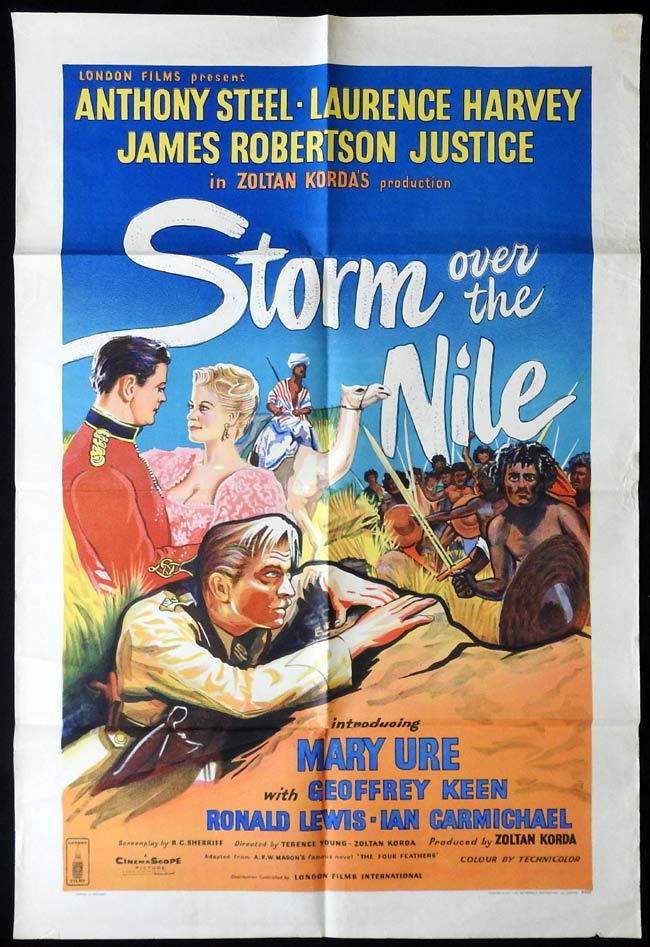

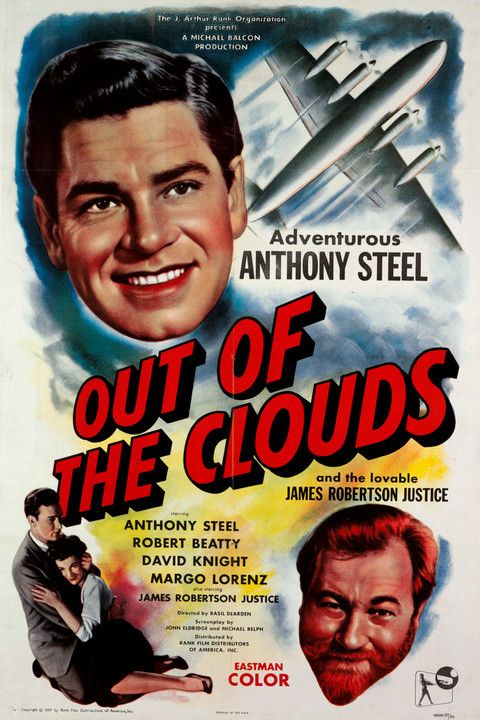

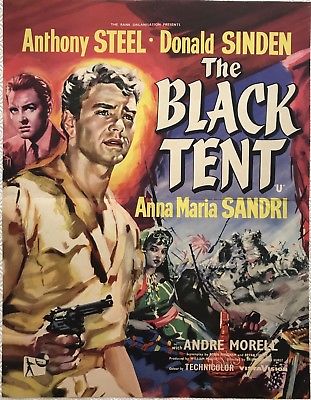

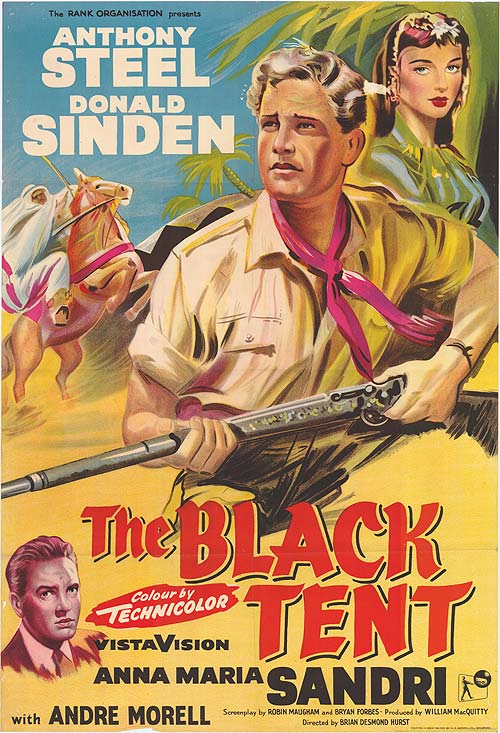

For the next few years, Steel was continuously busy, making, among others, the comedy Laughter In Paradise (1951), Another Man’s Poison, and the war stories, The Malta Story (1952) and Albert RN (1953). In 1955, it was The Sea Shall Not Have Them and, in 1956, Storm Over the Nile, The Black Tent and Checkpoint.

It might have continued like that, but Steel was accident prone – the worst being meeting Anita Ekberg in December 1955, though he had previously been run through the hand by Errol Flynn’s sword in The Master Of Ballantrae and injured his leg, requiring an operation on his knee, after colliding with a tree while making Where no Vultures Fly, in which he played a game warden in east Africa.

Steel met Ekberg after making Storm Over The Nile, a remake of The Four Feathers, in which an apparent coward turns out to be a hero. After their initial encounter, at a film premiere, he called her the most beautiful woman he had ever met. They married in Florence in 1956.

But while Steel was reserved and not at all stagey, Ekberg liked displaying herself, and there were soon rumours of drink-fuelled rows. Steel became prone to what was called “hellraising”; he hit photographers who pursued his wife, and was twice arrested for drink driving.

It all seemed to be out of character. He had been born into genteel circles in Chelsea, the son of an Indian army officer, and gone to school in Ireland before Cambridge. When the second world war broke out, he joined the Grenadier Guards, all of which sat perfectly with the reputation he was to make in the Britain of the postwar years.

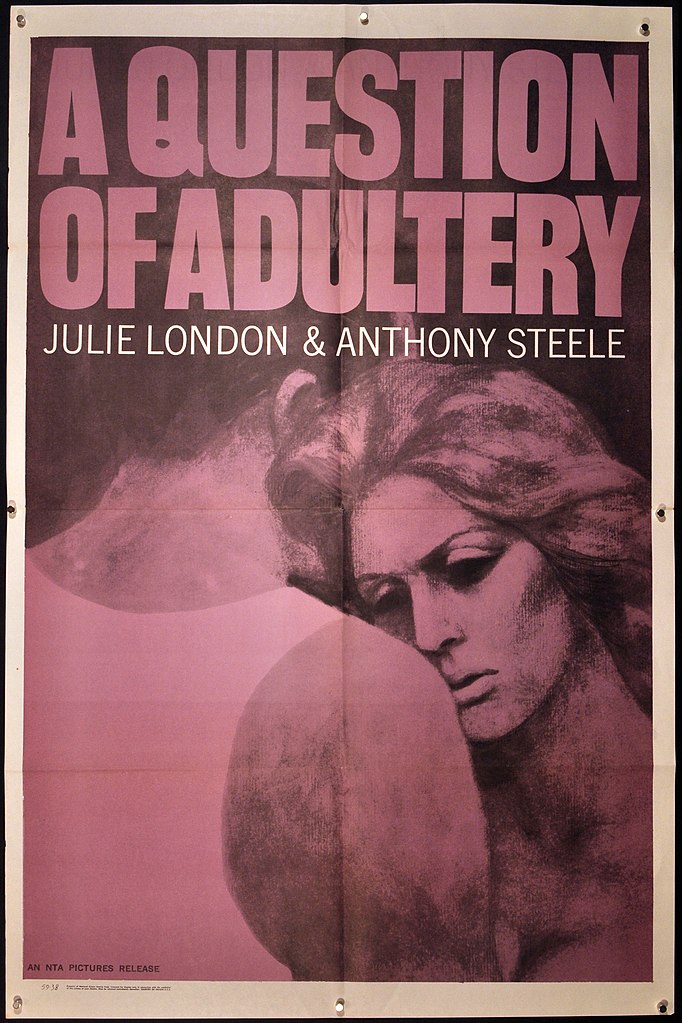

Some of his friends believe the collapse of his marriage to Ekberg was a disaster from which he never recovered emotionally; he had previously been married to Juanita Forbes and, after Ekberg, married Johanna Melcher, a former Miss Austria, in 1964. It is certainly arguable that he never recovered professionally, for when he returned to Britain at the end of the 1950s, the affronted British film industry showed little interest. His later films included Hard Core (1977), The Racing Game (1979) and the Swords Of Wayland (1986), none of them notable.

Apart from the stage tours of the 1980s, Steel’s last assignments were polished guest appearances in pop-ular television series such as Bergerac, The Professionals, Tales Of The Unexpected, Robin Of Sherwood and Jemima Shaw Investigates.

He leaves two daughters and a son.

Anthony Maitland Steel, actor, born May 21 1920; died March 21 2001 “The Guardian” obituary can also be accessed on-line here.

.