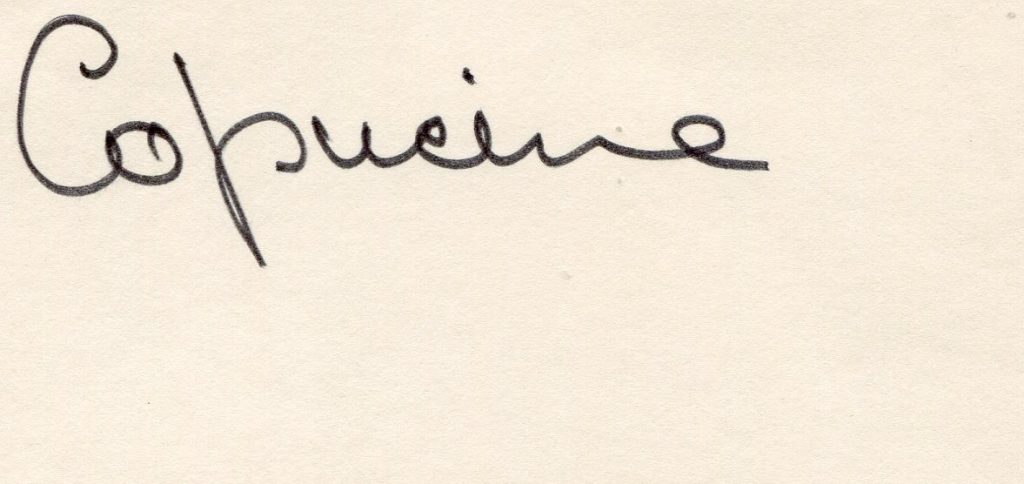

There have been some very famous mononymous persons – Cher, Sting, Björk, Plato – but of all of them, Capucine must have been the most beautiful. Blake Edwards, who directed her in The Pink Panther (1963), called her “part Mona Lisa. That smile”. Christian Dior, for whom she had modelled in Paris, was struck by her “old eyes, her eyes were impervious”.

These days, if you remember Capucine at all, it is probably from those Pink Panther films, in which she plays Inspector Clouseau’s wife, who can afford her conspicuous head-to-toe Yves Saint Laurent because she’s nicking jewels behind his back. (“On a police inspector’s salary! How many women could save enough out of the housekeeping to buy a mink coat?” asks the besotted Clouseau. “Well, it’s not easy!” she replies.)

The part of Madame Clouseau was also stolen, from Ava Gardner, who was dropped when she became too demanding. Capucine made a better mannequin for the outfits, not unexpectedly.

Born Germaine Lefebvre on the Côte d’Azur in 1928, she ran away to Paris as a teenager. There she became a couture model, discarded her dowdy name and met Audrey Hepburn, who would become her best friend. (She also once shared a cabin, as a cruise ship model in 1952, with a teenage nightclub dancer called Brigitte Bardot.)

Capucine is not thought a great actress – her co-star Laurence Harvey went so far as to call her “ghastly” – but she had a flair for physical comedy that was overlooked. Watch her in The Pink Panther strip off in the lift as her pursuers run up the stairs, so that she emerges (ding!) in total disguise, then grins with relief when she realises she’s fooled them. Capucine is good at switching from dignified to undignified and back again. The trouble is, she was very rarely required to.

Her point, as Hollywood saw it, was to fill the Grace Kelly slot after Kelly became actual royalty. In the words of William Goetz, the producer who gave Capucine her first lead, as the Russian princess Carolyne Wittgenstein, in a 1960 Dirk Bogarde vehicle: “You can teach a girl to act but nobody can teach her how to look like a princess. You’ve got to start with a girl who looks like a princess.”

This led to some frustrations. The press nicknamed her “the haughty heron”. In 1968, Capucine told an Italian magazine she wished she didn’t always have to be elegant, that she longed to play a “dishevelled woman”, but “since the directors know I was a model, it is obvious that they can’t see me as anything else.” In 1965, she told Time magazine: “Sometimes I feel I would like to cut loose and start throwing pies.”

For someone intended to fill Grace Kelly’s Cinderella slippers, Capucine’s own life turned out to be very uncharmed. Beauty was her great strength, but it was also a limiting factor. “Men look at me like I’m a suspicious-looking trunk, and they’re customs agents,” she once said.

As she aged, she felt unable to present the façade required, and stopped going out. The parts for countesses and princesses dried up. The director Luchino Visconti turned her down for Tadzio’s mother in Death in Venice (1971), a part Bogarde was angling for her, because: “She has a horrible voice and too many teeth. She looks like a horse, a beautiful horse, I know that, I was a trainer. I know all about horses, but I don’t want a horse.”

None of this might have mattered, but Capucine was also a suicidal depressive. Hepburn saved her life when she took an overdose of pills, but in 1990 she threw herself from the roof of her Lausanne apartment block. If she hadn’t, she would have been 90 today. She left $100,000 apiece to Unicef and the Red Cross, in honour of Hepburn; her ashes were scattered by Givenchy.

When Capucine died, little was known of her for sure. Her obituaries couldn’t even agree on the number of cats she left behind. Partly this was a symptom of her having been looked at all her life, rather than listened to; partly it was to do with her habit of gently fictionalising her life as she went along (arch in interviews, which she found dull, she invented new dates of birth); partly because she rarely bothered to correct misinformation printed about her.

Gossip columnists tied her up in various romances – to the producer Charles K Feldman, to her co-stars William Holden and Bogarde (who said she was the only woman he could ever have married) – but it isn’t clear whether any of these “love affairs” were real. “What is social, they want to make seem sexual,” she told Boze Hadleigh, the Hollywood historian.

The truth is that Capucine, who played Barbara Stanwyck’s love interest in Walk on the Wild Side (1962) and kissed Suzy Kendall on the lips – racy for the time – in Fräulein Doktor (1969), was bisexual off-screen, too. George Jacobs, Frank Sinatra’s valet, said she was one of the very few women who wouldn’t give Frank the time of day. Laurence Harvey, the male lead in Walk on the Wild Side, told her: “Kissing you is like kissing the side of a beer bottle.”

When Hadleigh interviewed Capucine for his book Hollywood Lesbians, she told him: “Most Americans think it’s either 100 per cent heterosexual or 100 per cent homosexual. It’s much more complex than that. Look at ancient Greece.” When asked if she would describe herself as heterosexual, she replied: “Oh, I wouldn’t. But if the publicity people would see a need to say that, I don’t care… most publicity is not true.”

Federico Fellini said of Capucine that “she had a face to launch a thousand ships… but she was born too late.” Perhaps. But would more recognition have made her happy? We will never know. Capucine was often described as “sphinx-like” in life, and now, in death, she really is