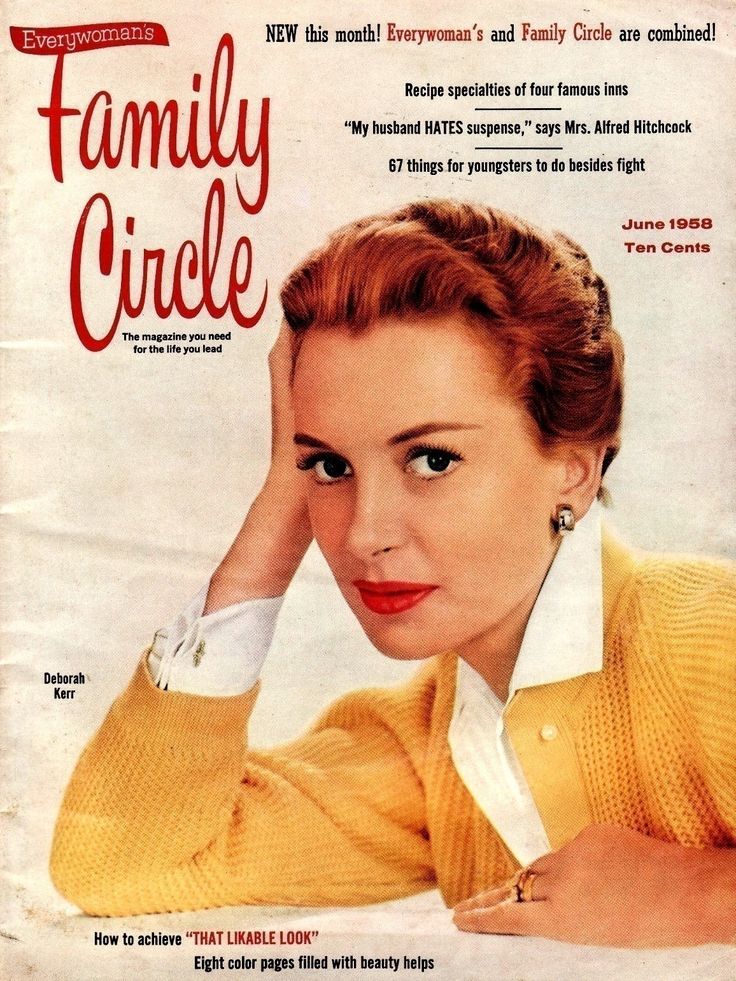

Deborak Kerr is rightly regarded as one of the most foremost of British actresses to reach true international stardom. Her CV of both British and U.S. films is extremely impressive. She was born in Glasgow in 1921. She originally trained as a ballet dancer with the Sadler Well’s Ballet Company. However she changed careers and in 1940 made her first film “Contraband” when she 19. She was soon in major roles in such films as “Major Barbara”, “Hatter’s Castle”, “The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp” and “Black Narcissus” in 1947. She then went to Hollywood and had to wait a few years before she obtained topflight roles. This was achieved with “From Here to Eternity” in 1953 and for the next eight years she gave some terrific performances e.g. “Tea and Sympathy”, “The King and I”, “An Affair to Remember”, “Seperate Tables” and “The Sundowners”. In the late 60’s her cinema career was waning and she returned with great success to the stage. She did though in the 80’s return to film with “The Assam Garden”. Sadly illness curtailed her later career and she died in 2007.

Her “Independent” obituary:

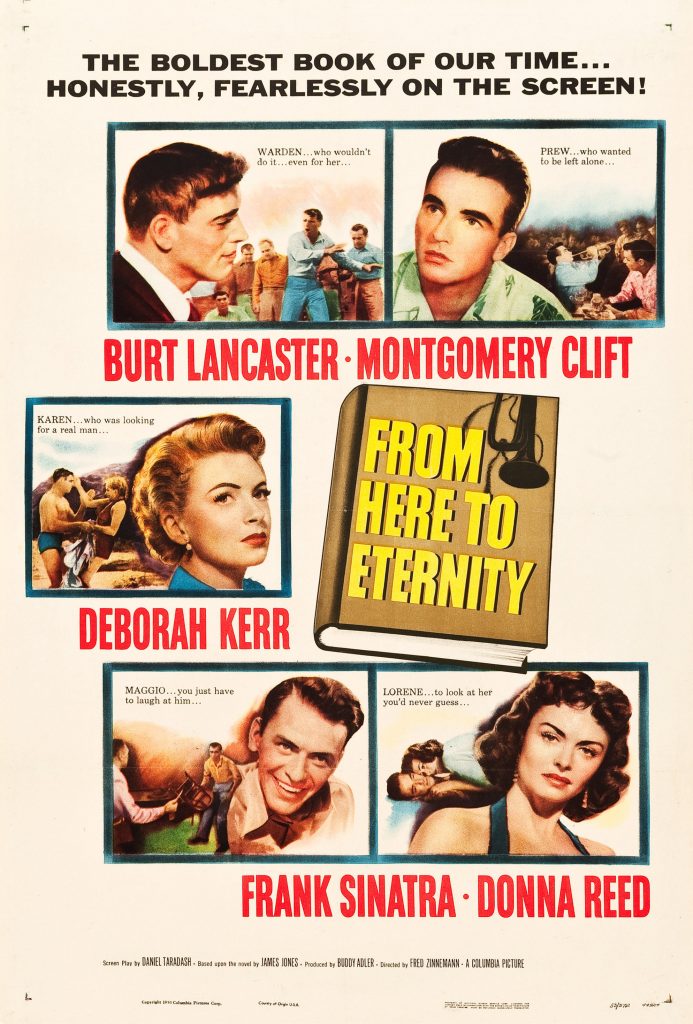

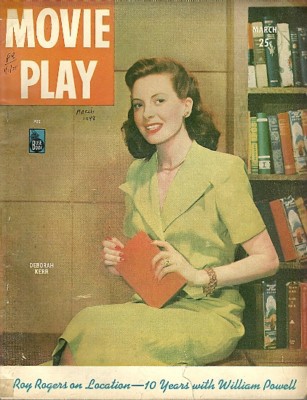

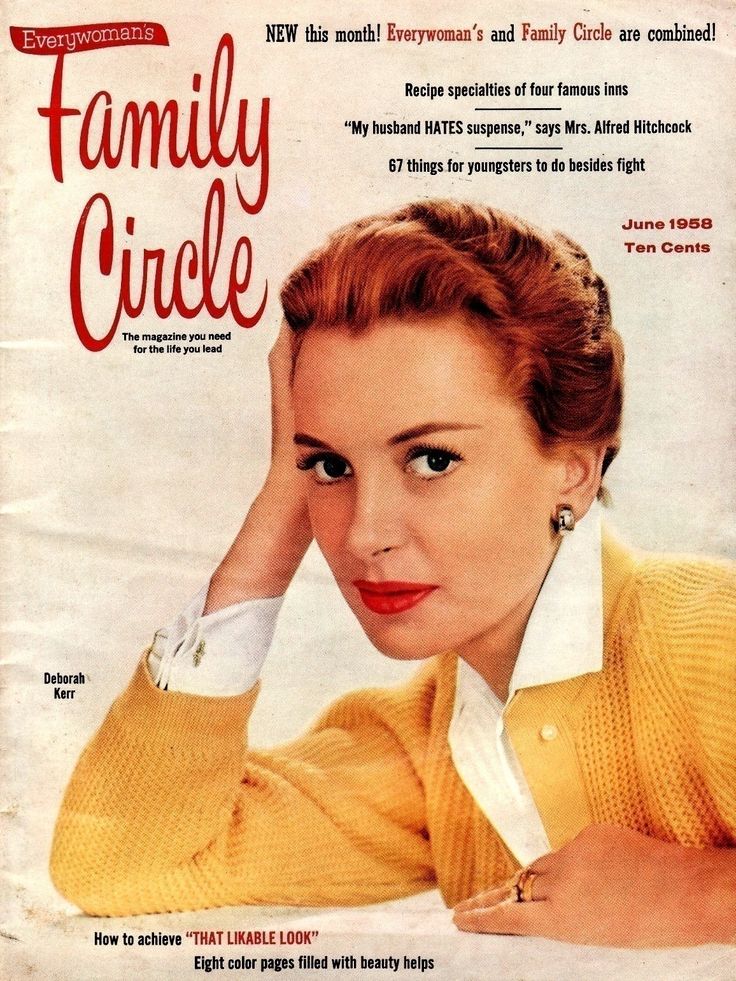

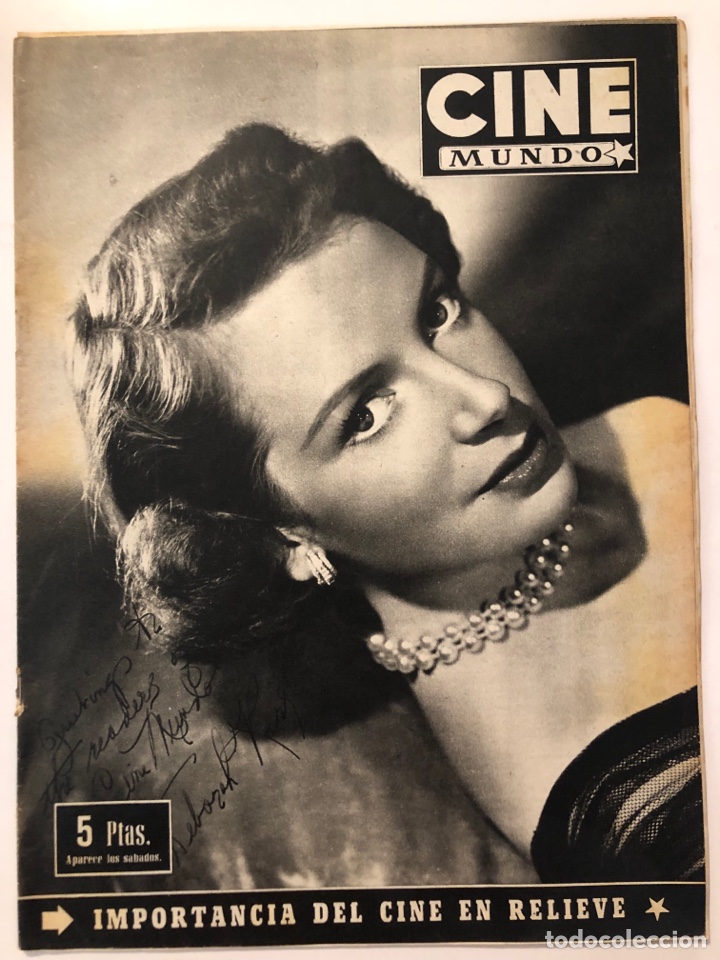

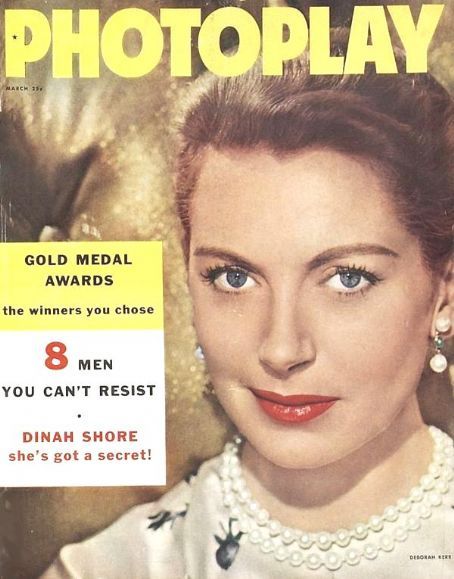

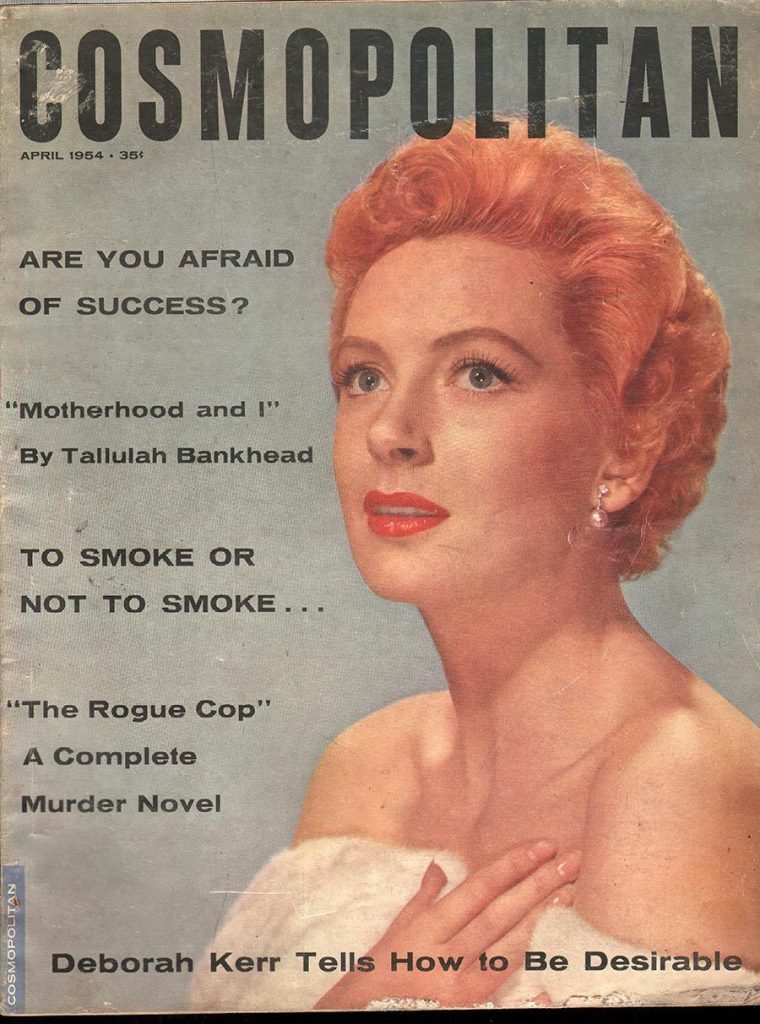

One of the few British actresses to become an internationally successful film star, in 1957 Deborah Kerr was named “The world’s most famous actress” by Photoplay magazine. She had had a highly successful career in British cinema before being poached by Hollywood. There she was regarded as little more than classy, patrician decoration before she famously shocked the town – and many of her admirers – with a steamy performance as the unfaithful wife of an army captain in From Here to Eternity (1953).

Her beach scene with Burt Lancaster, in which they make love as the raging surf envelops them, has become an iconic screen sequence, imitated and parodied as well as celebrated. Kerr’s accomplished skill and versatility resulted in six Oscar nominations (the most for any star in the Best Actress category who has not actually won).

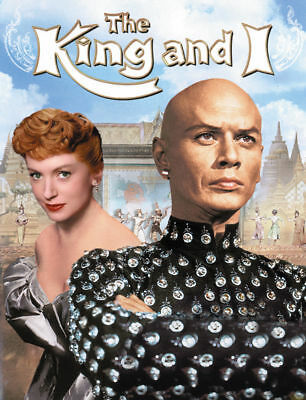

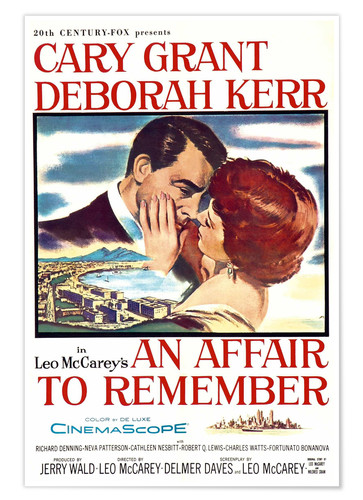

Her many memorable performances included the bewitchingly determined Irish spy of I See a Dark Stranger (1946), the repressed nun of Black Narcissus (1947), the downtrodden sheep-drover’s wife in The Sundowners (1960) and the ambiguous governess in The Innocents (1961). Perhaps best of all she is remembered for her work in two perennial classics of romantic cinema, the musical The King and I (1956), and the tear-jerker supreme, An Affair to Remember (1957). “I adore not being me,” she once said. “I’m not very good at being me. That’s why I adore acting so much.”

The daughter of a civil engineer, she was born Deborah Jane Kerr-Trimmer in 1921 in Helensburgh, overlooking the Firth of Clyde. As a child, she studied dance at a drama school in Bristol run by her aunt, winning a scholarship to Ninette de Valois’s Sadler’s Wells ballet group, with whom she made her London stage début at the age of 17.

Watching the progress of her fellow pupils Margot Fonteyn and Beryl Grey convinced Kerr that she would never be a great ballerina, so she concentrated on developing her acting skills and in 1939 did walk-on roles in several Shakespearean productions at the open-air theatre in Regent’s Park. She was spotted there by the powerful film agent John Gliddon, who signed her to a five-year contract.

Michael Powell’s lively thriller Contraband (1940) would have marked her screen début, but her role was excised from the final print. “The film was full of restaurants and night-clubs,” Powell wrote, “in one of which was an adorable little cigarette girl, all lovely liquid eyes and nice long legs, who had a tiny scene with Conrad Veidt that ended up on the cutting room floor.” Kerr was acting with the Oxford Repertory Players when spotted while dining at the Mayfair Hotel by a producer, Gabriel Pascal. Kerr recalled,

He came over to me and said, “Sweet virgin, are you an actress?” I said, “Yes,” and he said, “Then take down your hair, you look like a tart!”

Publicising her as “The Botticelli Blonde”, Pascal cast her as a Salvation Army officer, Jenny Hill, in Major Barbara (1940), based on Bernard Shaw’s play and starring Wendy Hiller and Rex Harrison. Kerr’s Jenny was described by her biographer Eric Braun as “a signpost to the kind of part in which she would excel – moral fortitude concealed by a frail appearance”. Her impressive performance led to her being given the leading role of Sally Hardcastle in a screen adaptation (much delayed by British censors) of Walter Greenwood’s bleak story of the working-class, Love on the Dole (1941), directed by John Baxter. Kerr’s spirited yet touching performance as a girl who becomes the mistress of a wealthy bookie to escape poverty established that a major British star had arrived.

Leading roles in Penn of Pennsylvania (1941), Hatter’s Castle (1941) and The Day will Dawn (1942) followed, before the first of her film classics, Powell and Pressburger’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943). When Wendy Hiller, originally cast, became pregnant and had to drop out, Powell gave to Kerr the challenging assignment of the colonel’s ideal woman, who comes into his life in three separate incarnations over a 40-year period. Each incarnation was given individuality by her incisive playing. During the filming, she and Powell became lovers. “I realised,” said Powell, “that Deborah was both the ideal and the flesh-and-blood woman whom I had been searching for.” The film was controversial (Churchill thought it would ruin wartime morale, and the British army refused co-operation), but it proved an artistic and commercial triumph.

Powell had hoped to reunite Kerr and Roger Livesey, who had played Blimp, in his next film, A Canterbury Tale (1944), but Gabriel Pascal had sold her contract to MGM. According to Powell, his affair with Kerr ended when she made it clear to him that she would acccept an offer to go to Hollywood if one was made.

Her first film for MGM paired her with Robert Donat in the British production Perfect Strangers (1945), about a dull couple whose personalities are changed by their wartime experiences. Stewart Granger, who was filming Caesar and Cleopatra at the time, recounts in his autobiography Sparks Fly Upward (1981) that during this period Kerr (whom he described as “devastatingly beautiful”) seduced him in the back of a taxi. Whenever this was mentioned to Kerr by interviewers, she would smile wryly and reply, “What a gallant man!”

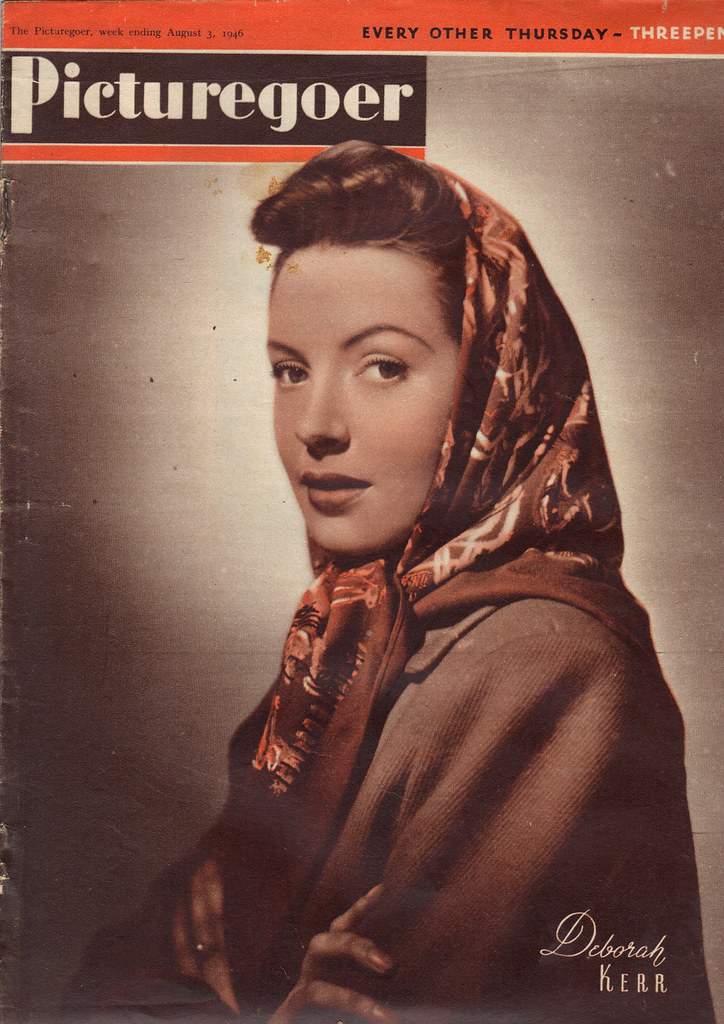

In 1945 she and Granger made an eight-week tour of theatres of war in Belgium, Holland and France starring in Patrick Hamilton’s thriller Gaslight. During the tour Granger introduced her to the Battle of Britain pilot Anthony Bartley, who became her first husband. Kerr’s next film was Launder and Gilliatt’s thriller I See a Dark Stranger (1946), in which she was Bridie Quilty, a high-spirited Irish lass. With Kerr and her co-players Trevor Howard and Raymond Huntley all making the most of the witty script, it was a delight.

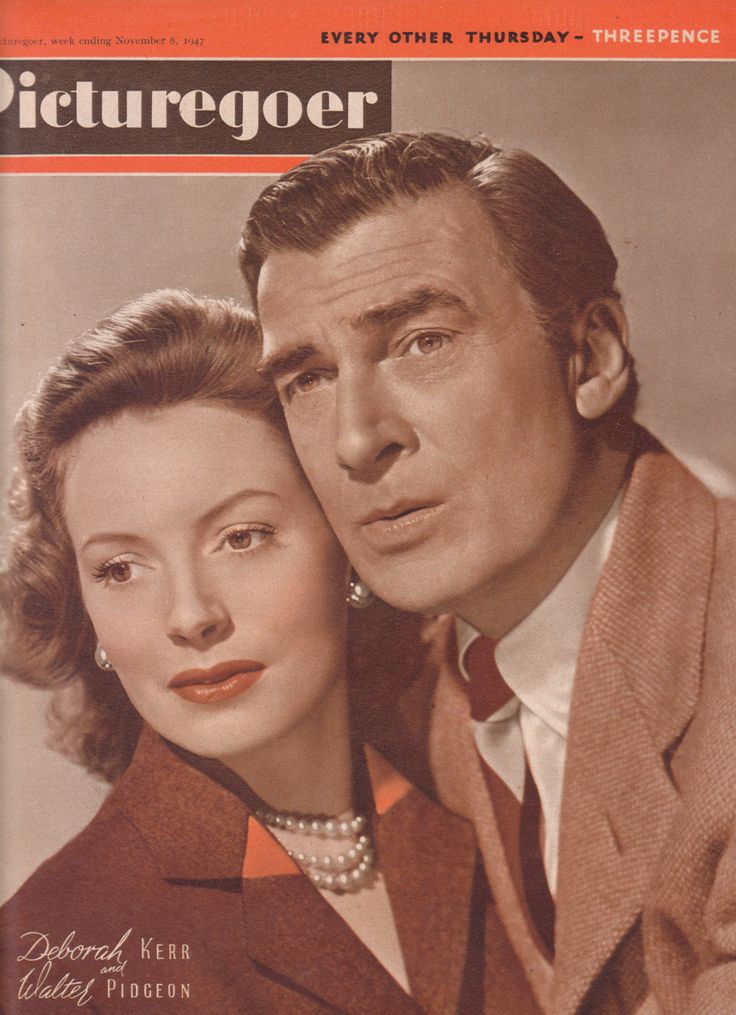

MGM then loaned her to Powell to star in Black Narcissus (1947). He had initially thought of trying to lure Greta Garbo out of retirement to play the part of troubled Sister Superior, in charge of a group of nuns who try to establish a community from a dilapidated palace in a remote part of the high Himalayas (created entirely at Pinewood). Black Narcissus was a hit in the US as well as the UK, and Kerr won the New York Film Critics’ Award as Actress of the Year. MGM was now ready to launch her American career, and she departed for Hollywood with her husband.

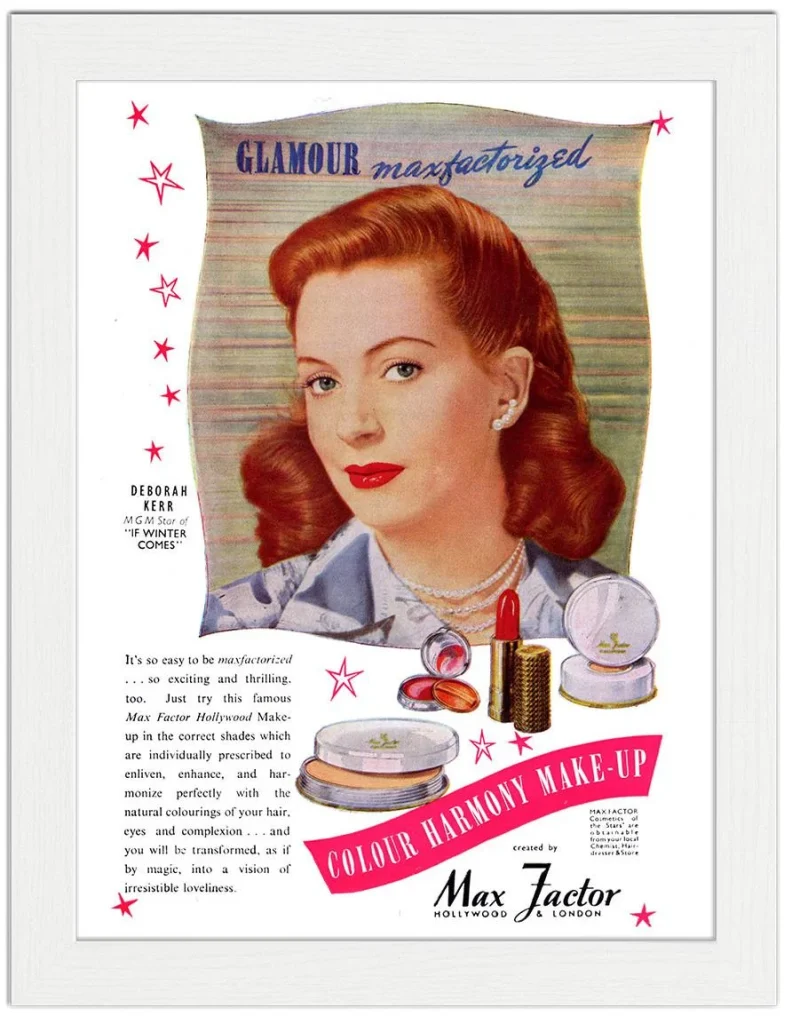

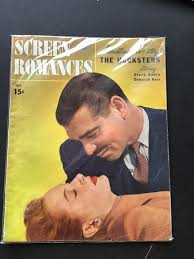

Advertisements for her first film, The Hucksters (1948), proclaimed her as “Deborah Kerr (rhymes with star)” and her photograph was on the cover of Time magazine, tellingly set against a background of English roses. The screenwriter Luther Davis recalled, “The studio were rather in awe of Deborah, treating her like this great legitimate actress who’d deigned to join MGM.” The Hucksters, a satire on radio advertising, was a moderate success, but it was followed by If Winter Comes (1949), a clumsily told melodrama that received limited release.

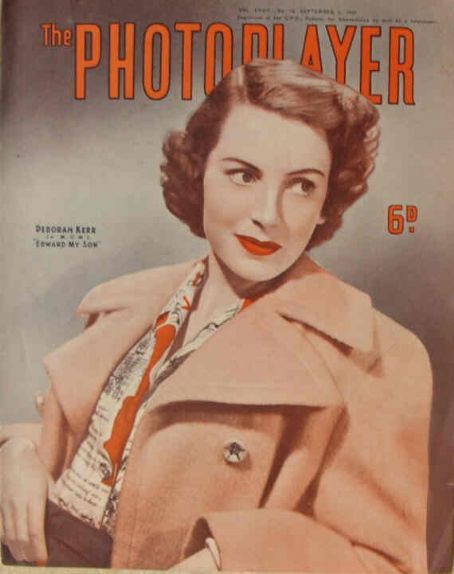

Kerr had the meaty role of a wife who descends into alcoholism in the screen version of Robert Morley’s play Edward, My Son (1949), and her uncompromising performance won her an Oscar nomination, but the downbeat tale, co-starring Spencer Tracy, did not attract large audiences. Her next film, Please Believe Me (1949), was a minor comedy with Peter Lawford and, unhappy, she told the studio head Dore Schary that there was a story she would love to do, The African Queen.

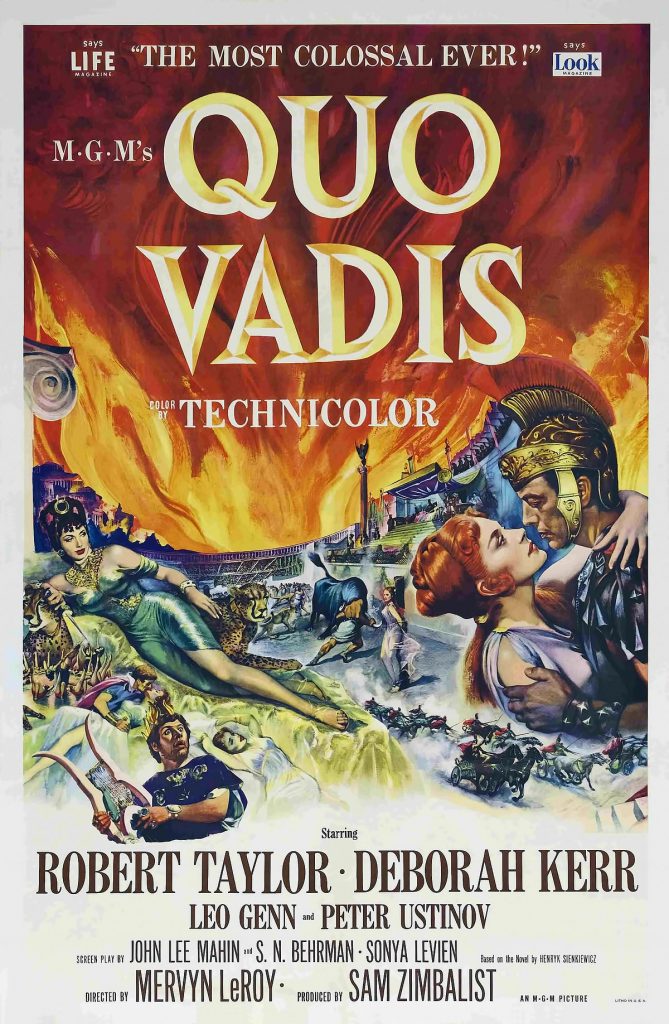

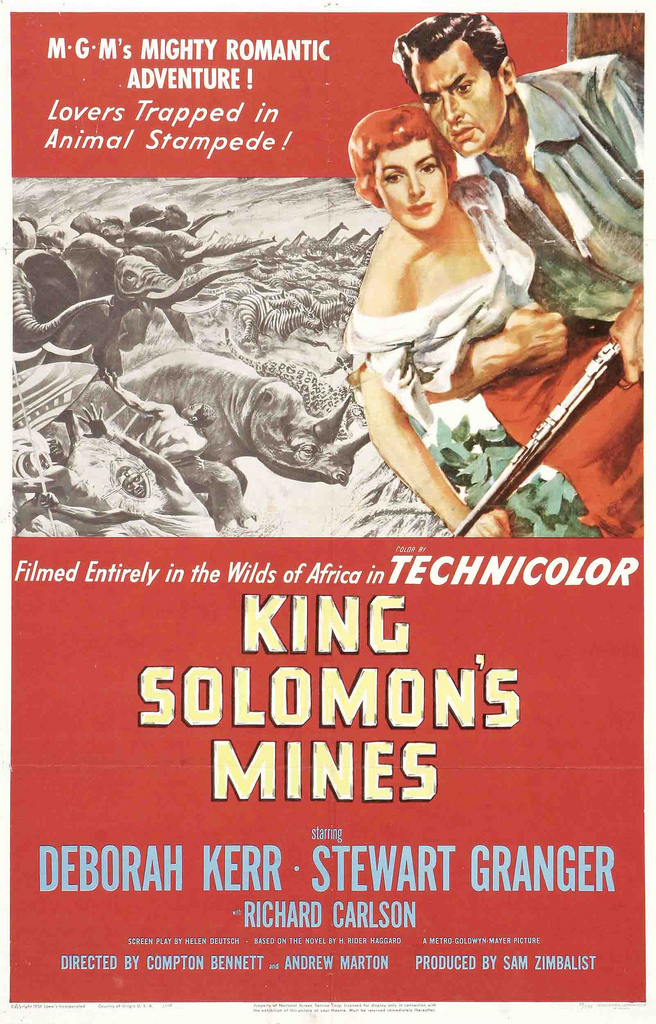

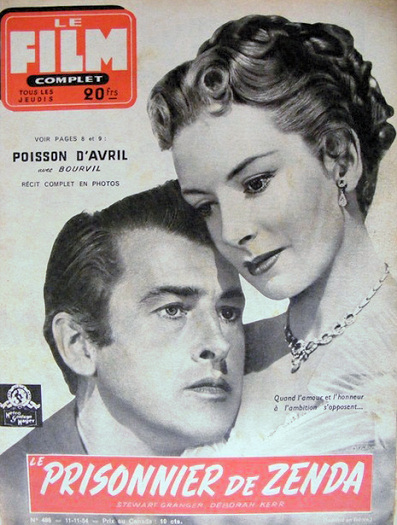

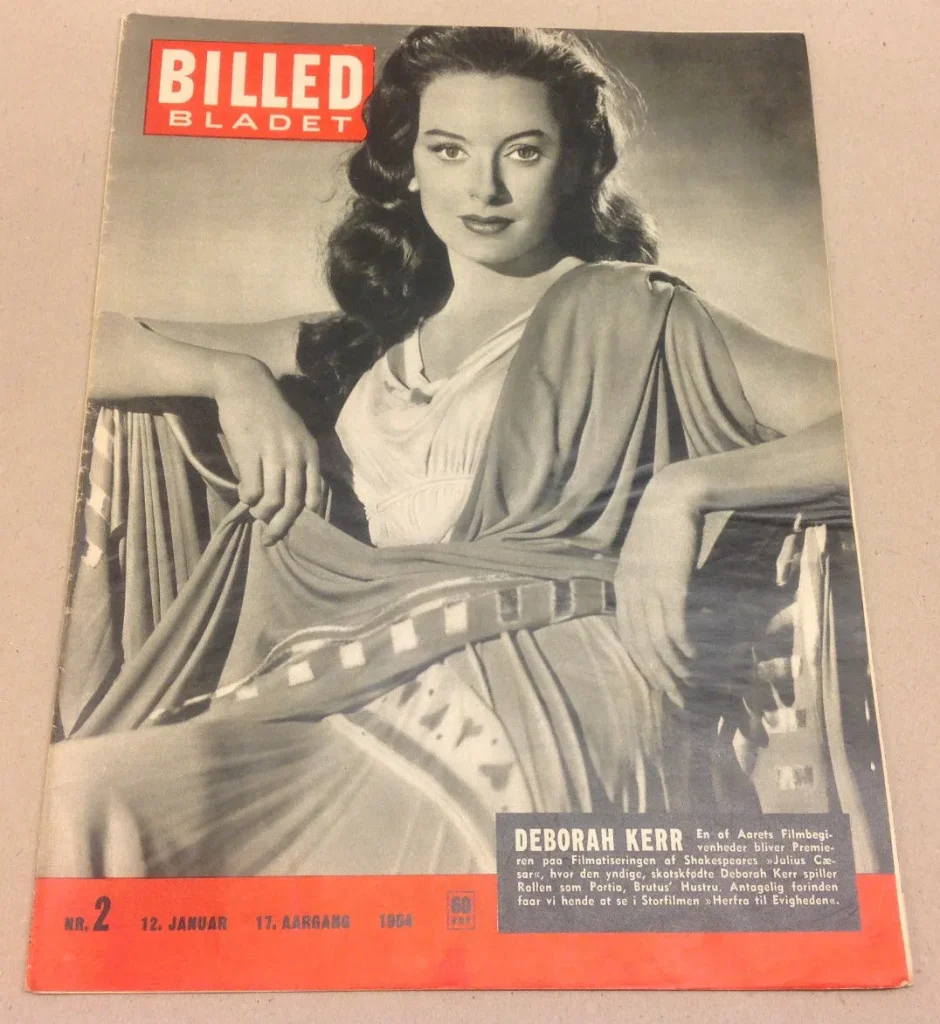

He replied that the property was owned by Warners, but that he had another African tale, King Solomon’s Mines (1950). “The next thing I knew I was on location 25,000 miles into darkest Africa.” Co-starring Stewart Granger, the film was a great success, and was followed by another blockbuster, the big-budget epic Quo Vadis? (1951), to which she brought her best patrician nobility as Lygia, the Christian slave girl. She was stoic again in Richard Thorpe’s excellent remake of The Prisoner of Zenda (1952).

She was happy to play the small role of Portia in Julius Caesar (1953), but was then given the role of Catherine Parr in Young Bess (1953), in which both she and Stewart Granger played second fiddle to the performances of Jean Simmons (as Bess) and Charles Laughton (as Henry VIII). “I came over to act,” she said, “but it turned out all I had to do was to be high-minded, long-suffering, white-gloved and decorative.”

After asking for MGM to let her freelance between assignments, she was delighted when a new agent, Bert Allenberg, persuaded the Columbia chief Harry Cohn to cast her as Karen Holmes in From Here to Eternity when Joan Crawford, originally given the part, walked out after requesting her own cameraman. Under Fred Zinnemann’s direction, Kerr effectively conveyed the sad, quiet desperation of her character, an alcoholic nymphomaniac. Said Kerr, “I studied voice for three months to get rid of my accent and I changed my hair to blonde. I knew I could be sexy if I had to.”

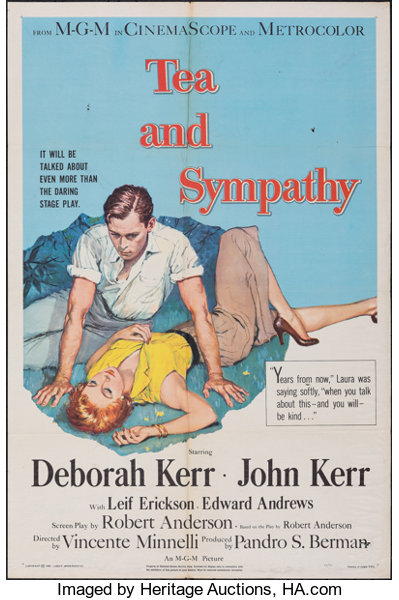

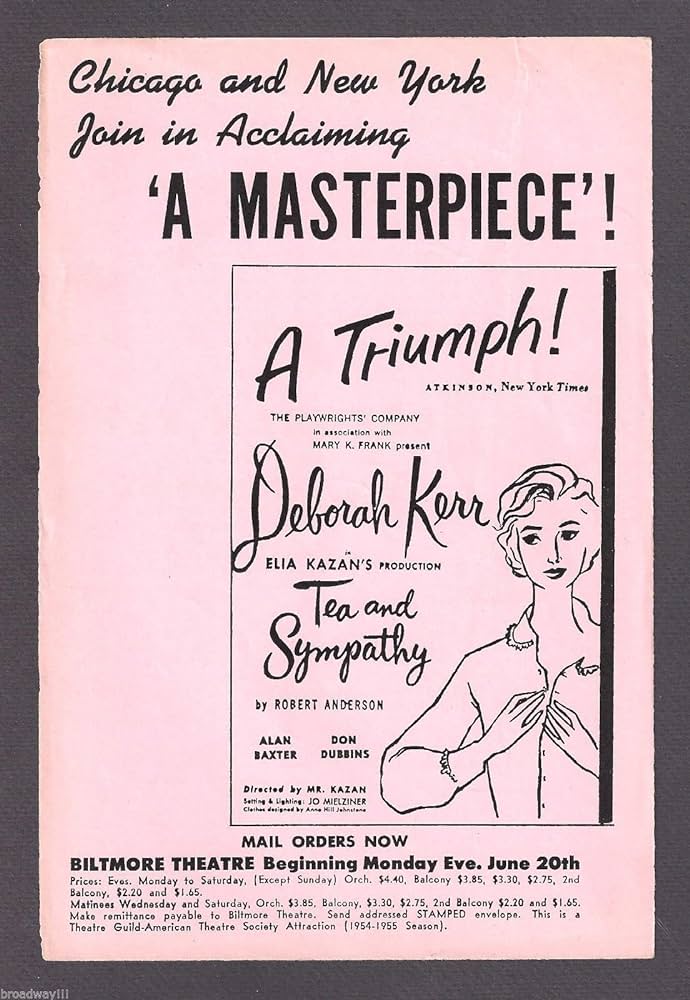

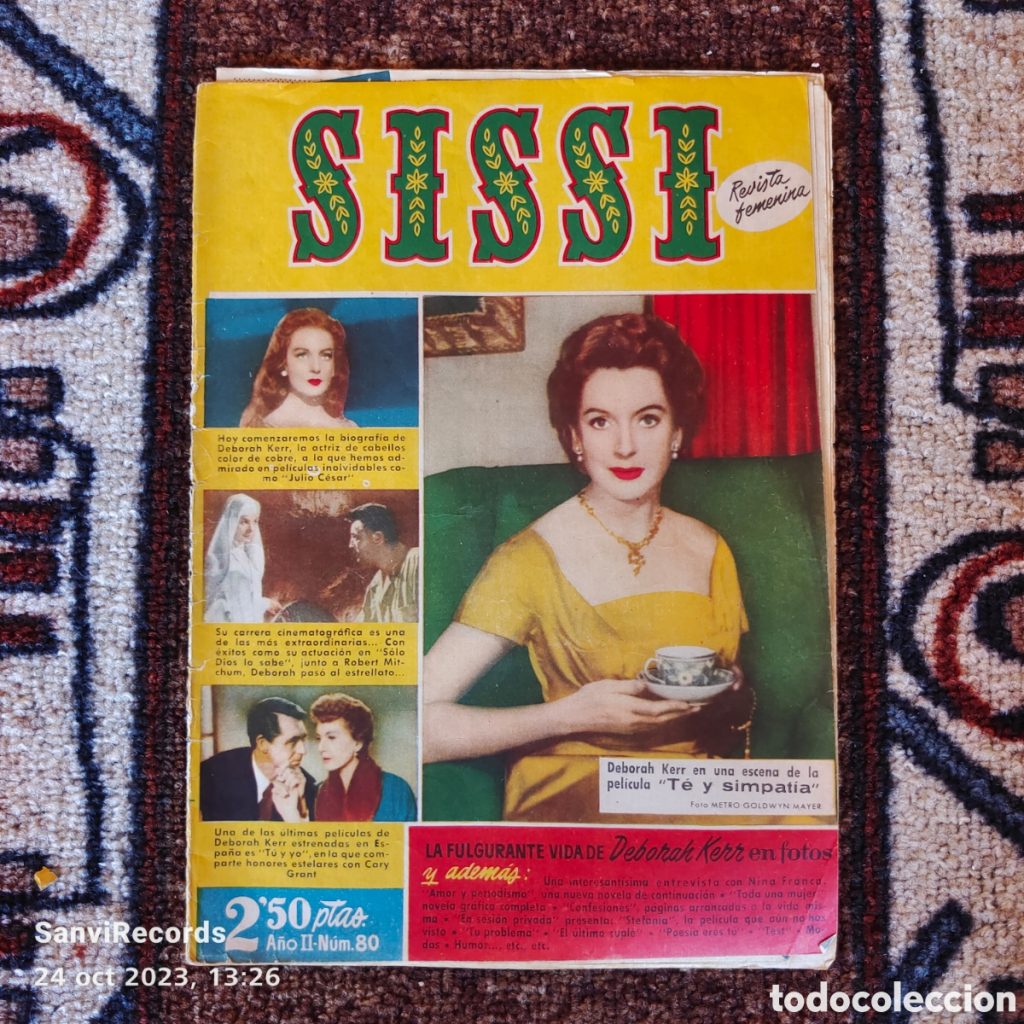

A third Oscar nomination resulted, and she consolidated her new status with her début on the Broadway stage in Robert Anderson’s Tea and Sympathy (1953), as Laura Reynolds, the schoolmaster’s wife who offers compassion to a troubled pupil suspected of homosexuality. In the controversial closing scene, she seduces the boy for his own good, and has one of the most famous closing lines in modern drama, “Years from now, when you talk about this – and you will – be kind.” The performance earned her two Donaldson Awards, (Best Actress and Best Début), the Variety Drama Critics’ Poll, and when she toured in the play she won Chicago’s Sarah Siddons Award.

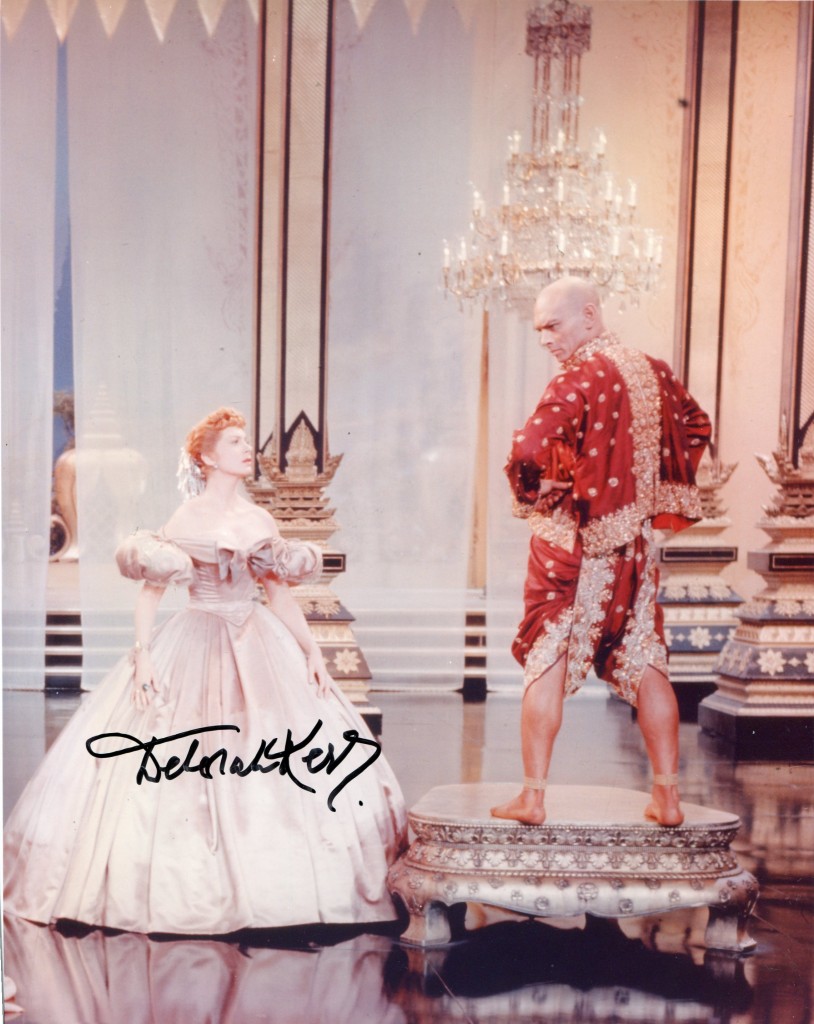

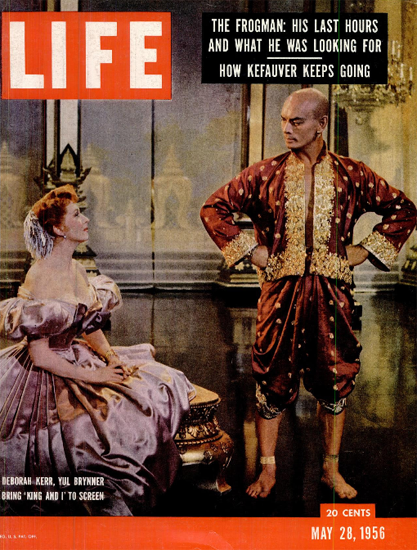

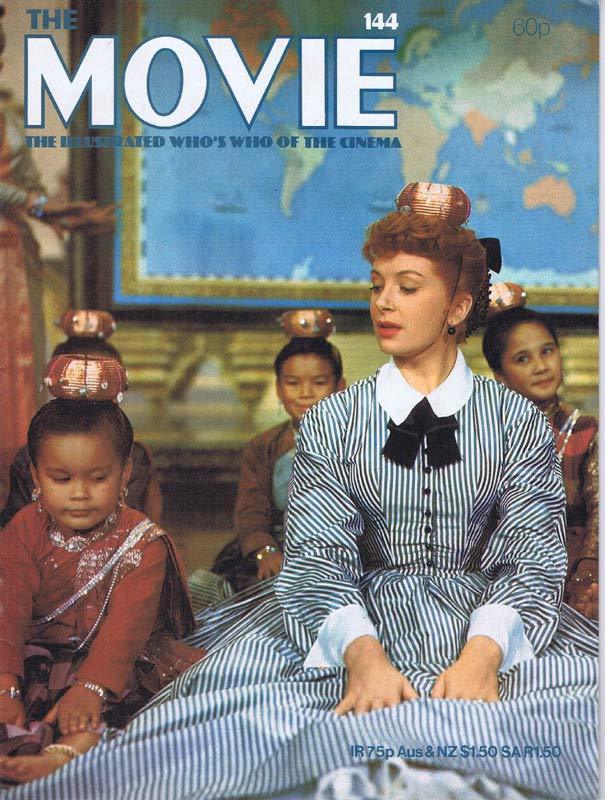

She returned to the screen in Edward Dmytryk’s British-made The End of the Affair (1955), and followed this with one of her greatest triumphs, as Anna Leonowens, the governess who travels to Siam to teach the King’s many children, in The King and I, Walter Lang’s screen version of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. Victorian determination sparked her spirited exchanges with the King (Yul Brynner), genteel warmth pervaded her scenes with the children, and the voice of Marni Nixon blended seamlessly with Kerr’s own recitative introductions to the songs, resulting in one of Hollywood’s finest dubbing achievements. Kerr was nominated for an Oscar, and Brynner won one for his forceful portrayal.

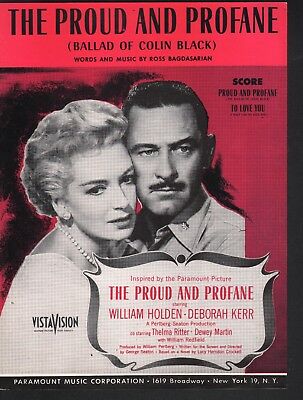

In 1957 Kerr was seen in the screen version of Tea and Sympathy. Although stylishly directed by Vincente Minnelli, the project inevitably suffered from the screen censorship of the time. Kerr’s Hollywood career was now at its peak. She starred with William Holden in The Proud and Profane (1956), Holden describing her as “the most no-problem star I ever worked with, and she has a salty sense of humour which surprises everyone”. She played a nun again, teamed with Robert Mitchum (“Such a wonderful actor”) in Heaven Knows, Mr Allison (1956), for which she received her fourth Oscar nomination, then starred with Cary Grant in An Affair to Remember (1957), one of her best-loved films. As a couple who fall in love during an ocean trip, and promise to meet in six months if they feel the same, Grant and Kerr merge a delightfully light bantering touch with suggestions of genuine passion.

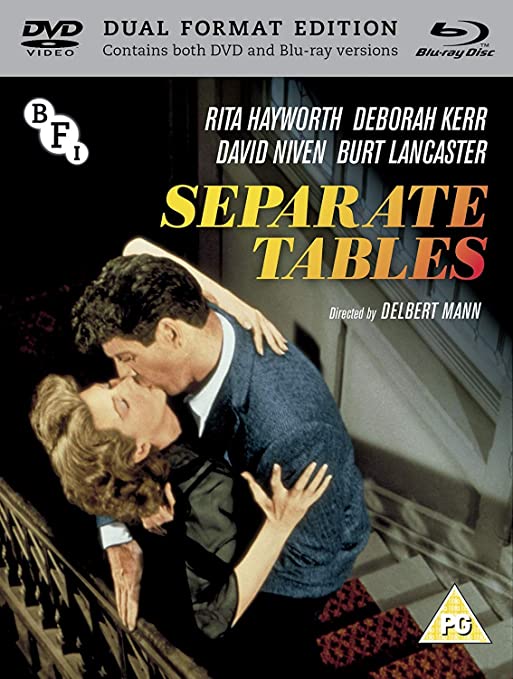

The following year Kerr won her fifth Oscar nomination, for her depiction in Separate Tables of a dowdy spinster cowed by a domineering mother. It is one of the actress’s most debated performances, detractors finding it too studied, though few will deny the frisson of the moment when she finally defies her mother and consorts with the disgraced, phony major (David Niven, in another instance where Kerr’s co-star won a statuette but she did not). She had an entirely different role with Niven in Otto Preminger’s under-rated version of Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse (1958), playing the glamorous widow Anne, whom Niven’s daughter (Jean Seberg) sees as a threat to the life-style she enjoys with her father.

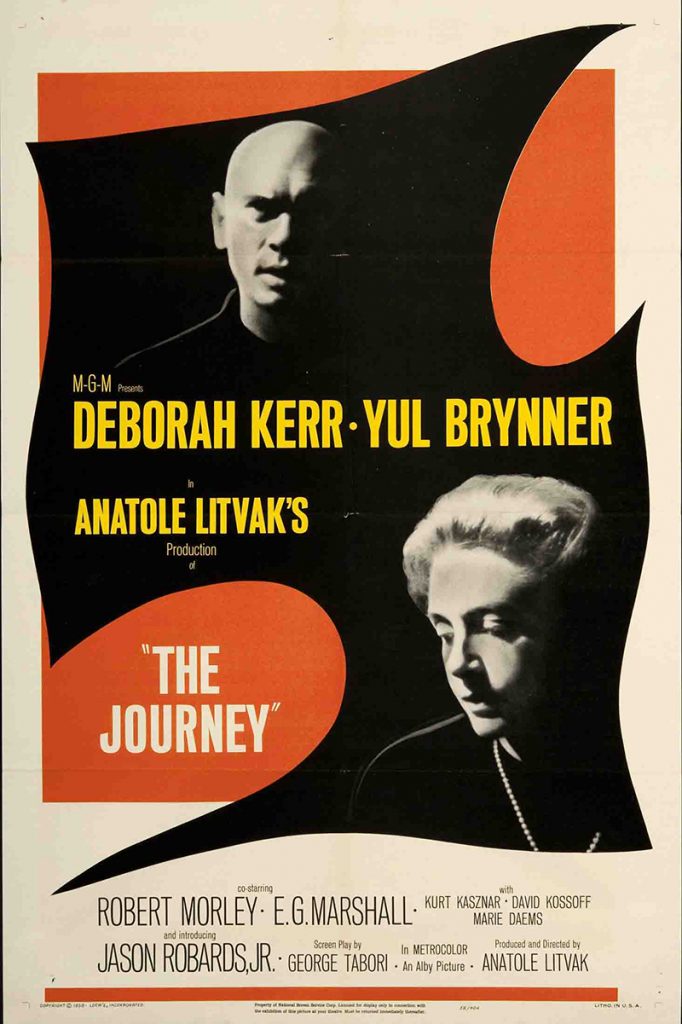

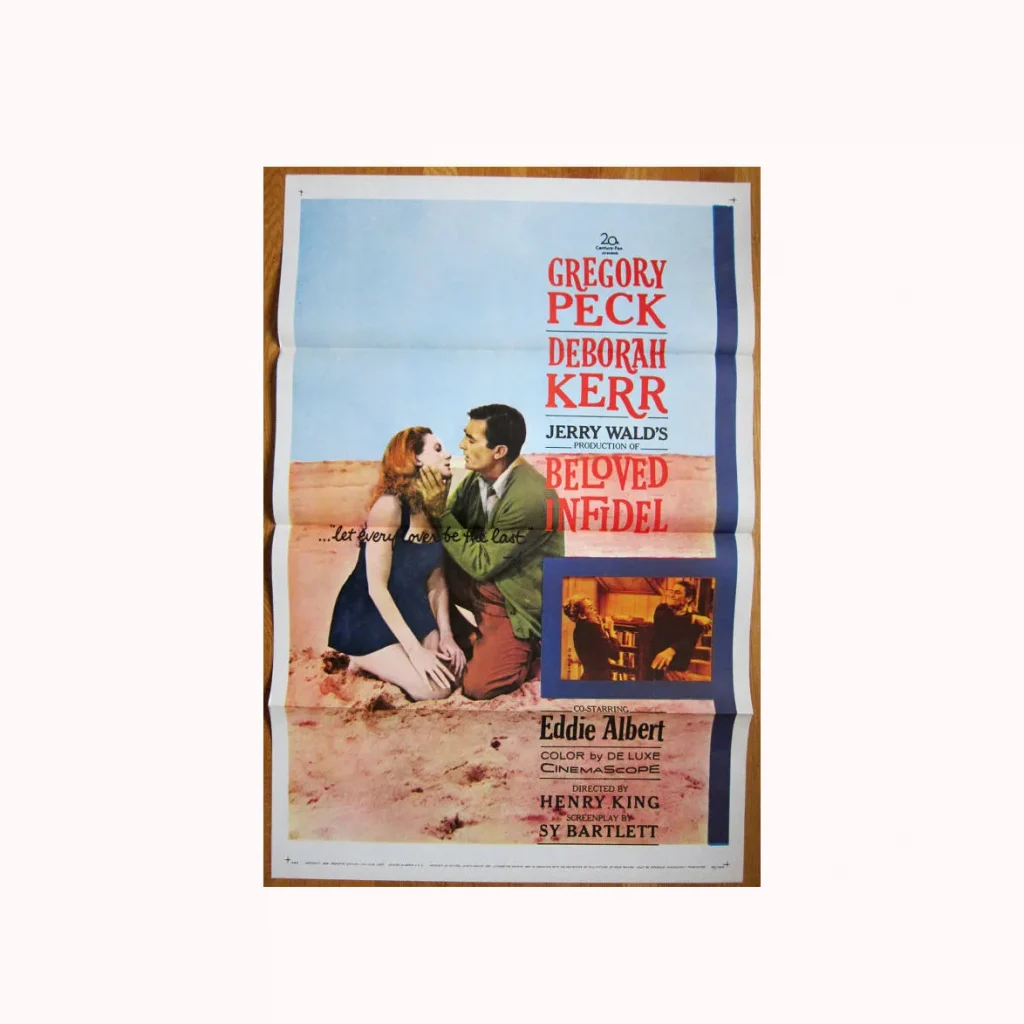

She partnered Brynner again in the cold war thriller The Journey (1958), co-written by Peter Viertel, who was to become her second husband. She played the columnist Sheilah Graham in Beloved Infidel (1959), based on Graham’s account of her tempestuous love affair with the writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, but the film was diluted when Gregory Peck agreed to play Fitzgerald only on condition that the first part of the script, dealing with Graham’s fascinating rise to fame, was excised.

In 1960 Kerr submerged completely any trace of her patrician persona with an immensely moving depiction of a downtrodden sheep-drover’s wife in Fred Zinnemann’s The Sundowners. It features one of the most memorable moments in Kerr’s career, as her weatherbeaten Ida, sitting on a station platform, sees an elegant woman adjusting her make-up in a train compartment, and the ladies’ eyes meet in mutual rapport.

It is the performance which many think should at last have won her the Oscar – it was the year Elizabeth Taylor won for Butterfield 8. “I should have won that year,” she told the writer Christopher Frayling, “I should’ve!” It is an undoubted miscarriage of justice that Kerr was not made a Dame, though she was appointed CBE in 1997. She won the New York Critics’ Awards for her performances in Heaven Knows, Mr Allison and Separate Tables, was given a British Film Institute Fellowship in 1986, and received a Bafta Special Award in 1991.

In 1961 Kerr made Jack Clayton’s The Innocents, arguably (with Robert Wise’s The Haunting) one of the two best ghost stories of the Sixties. She was superb as the enigmatic governess who comes to believe that her two charges are possessed by an evil spirit in this superb transcription of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw. Although she was fine as the mysterious Miss Madrigal, a governess with a criminal past, in The Chalk Garden (1963), and particularly as the kind and gentle artist in The Night of the Iguana (1964), based on Tennessee Williams’s play, a string of second-rate movies caused her career to dim in the mid-Sixties.

Marriage on the Rocks (1965), Eye of the Devil (1966), in which she replaced Kim Novak, Casino Royale (1967) and Prudence and the Pill (1968) were all poorly received, and John Frankenheimer’s The Gypsy Moths (1969) pleased critics more than audiences. It was her last film for 13 years, Kerr announcing her retirement from films and stating afterwards, “I didn’t want to do disaster movies, ending up in an airplane at the bottom of the sea.”

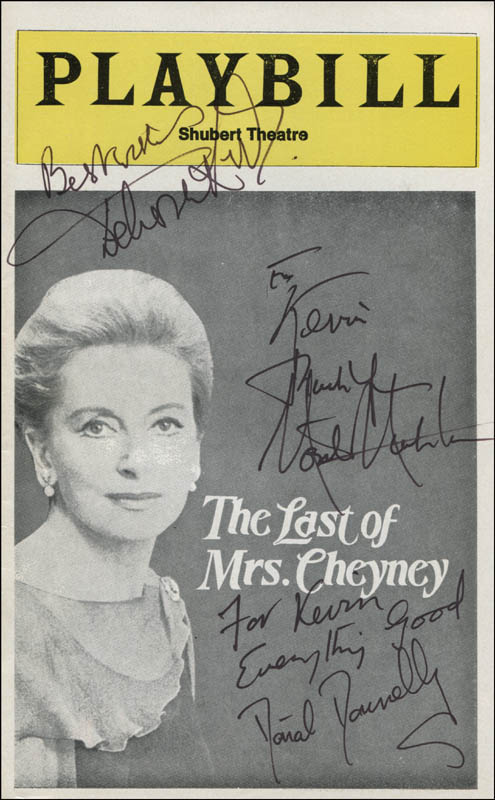

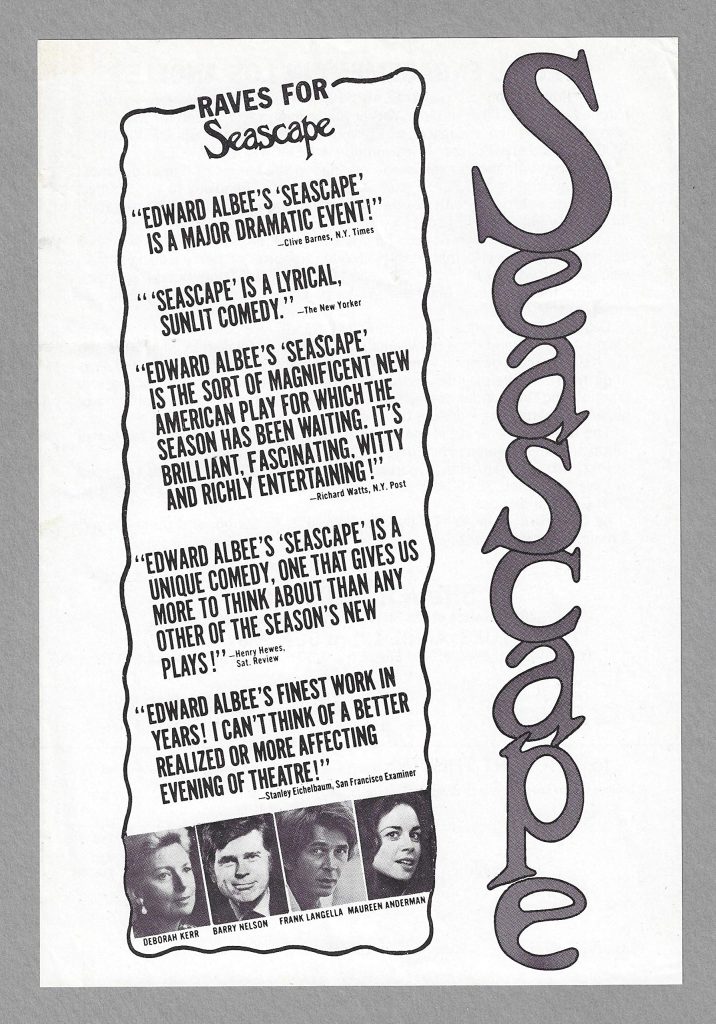

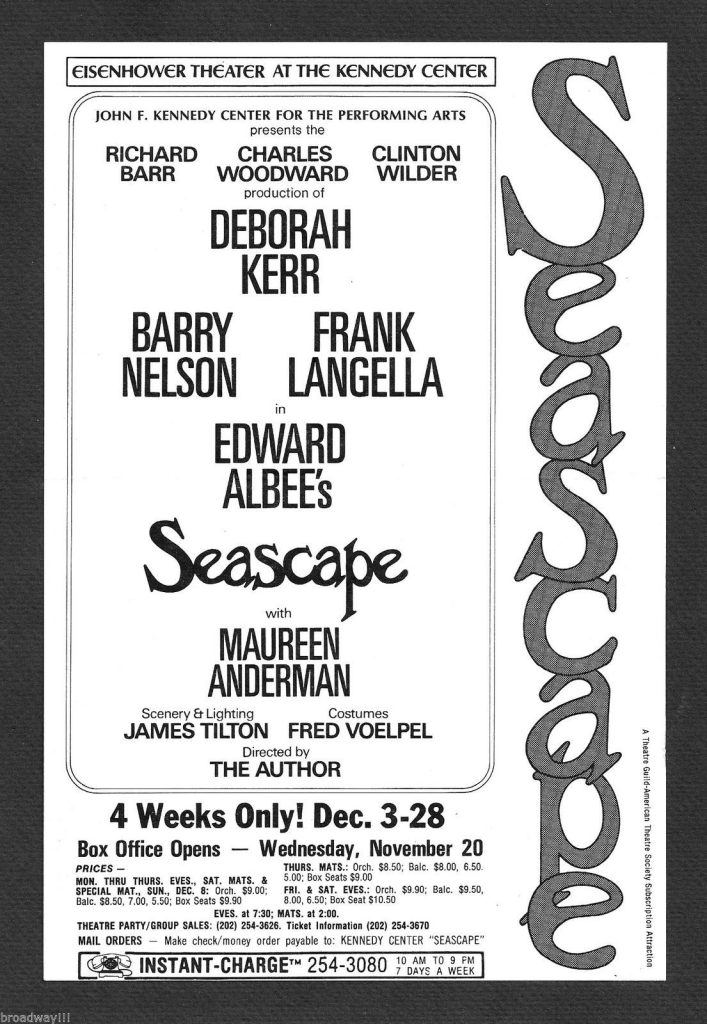

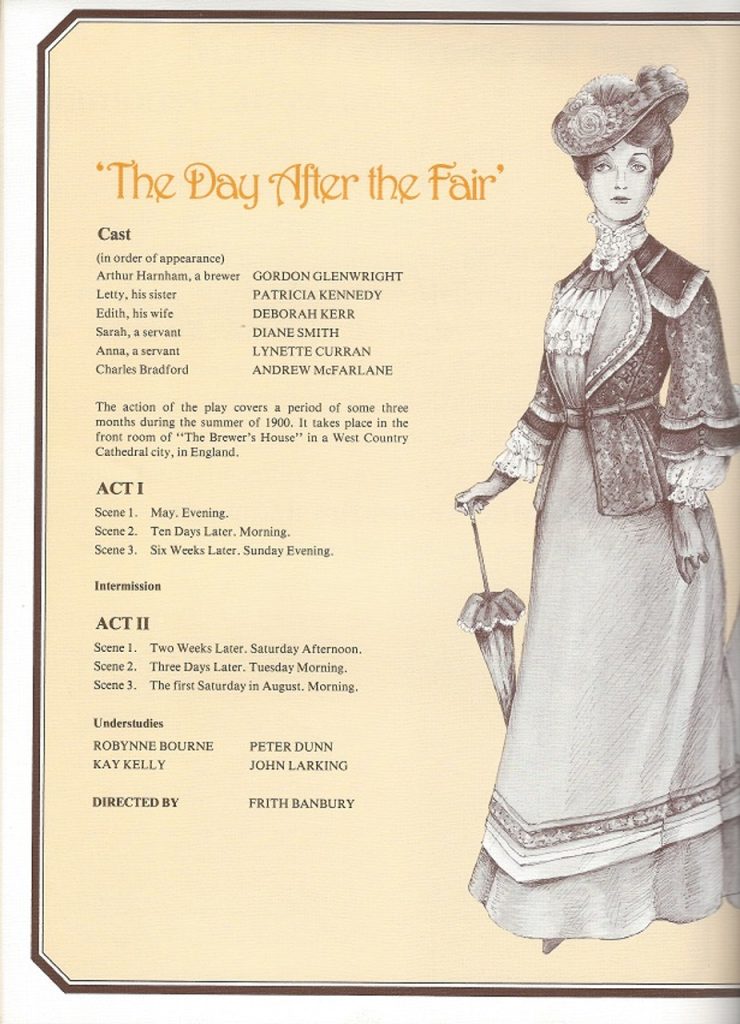

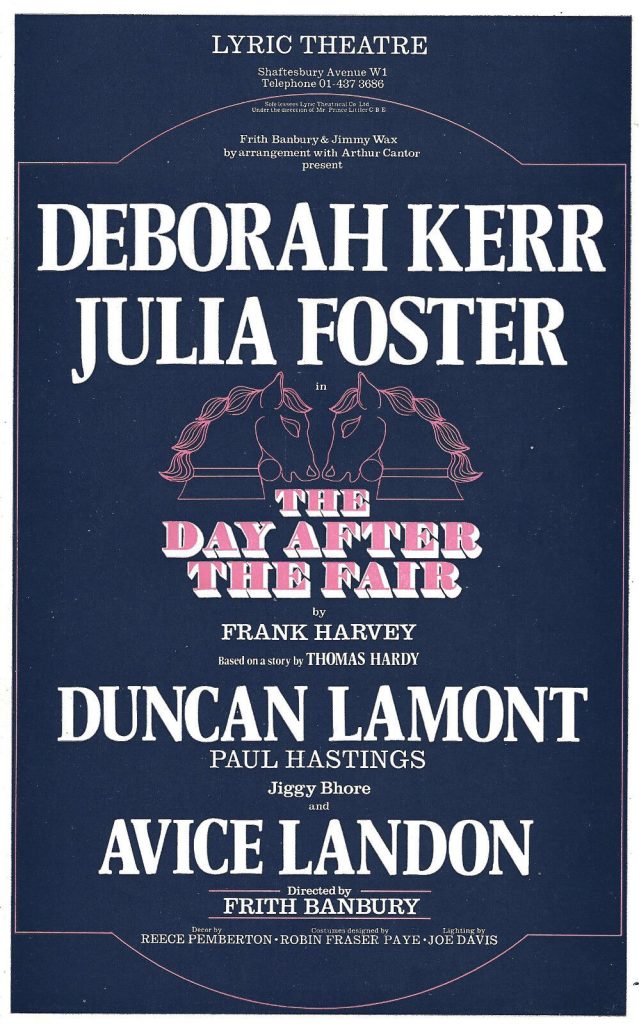

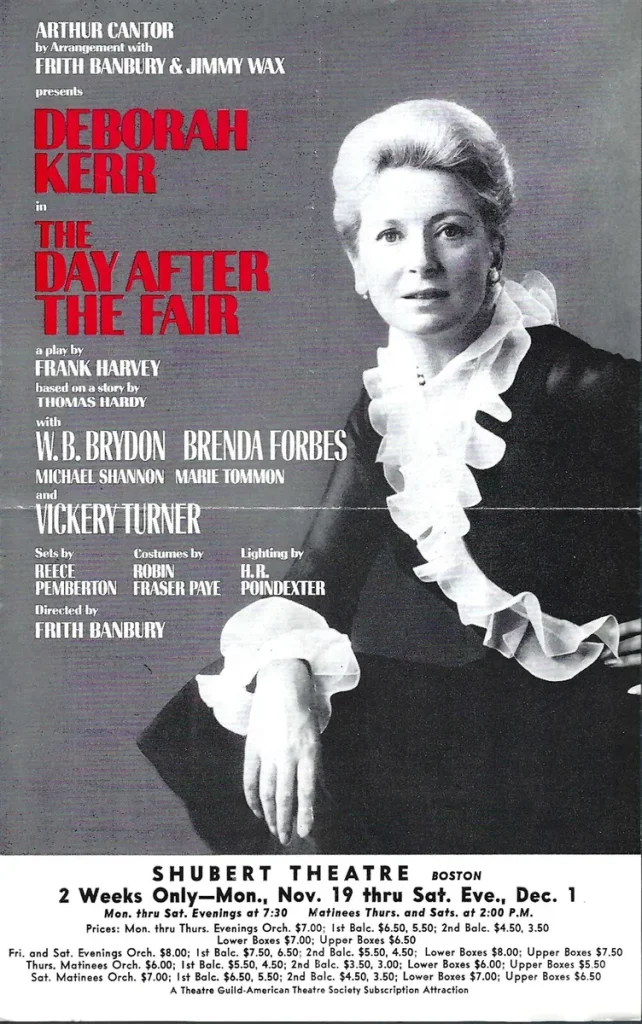

She returned to the theatre in 1972, recreating her role in Separate Tables in a one-performance Midnight Matinee in honour of Sir Terence Rattigan. Later that year she had a personal success in a West End production of The Day After the Fair, an adaptation of Thomas Hardy’s short story “On the Western Circuit”. The following year she toured the United States and Canada in the same play. In 1975 she starred on Broadway in Edward Albee’s short-lived Seascape, and in London she played the title role in Shaw’s Candida (1977). She returned to film in a television movie of Agatha Christie’s Witness for the Prosecution (1982).

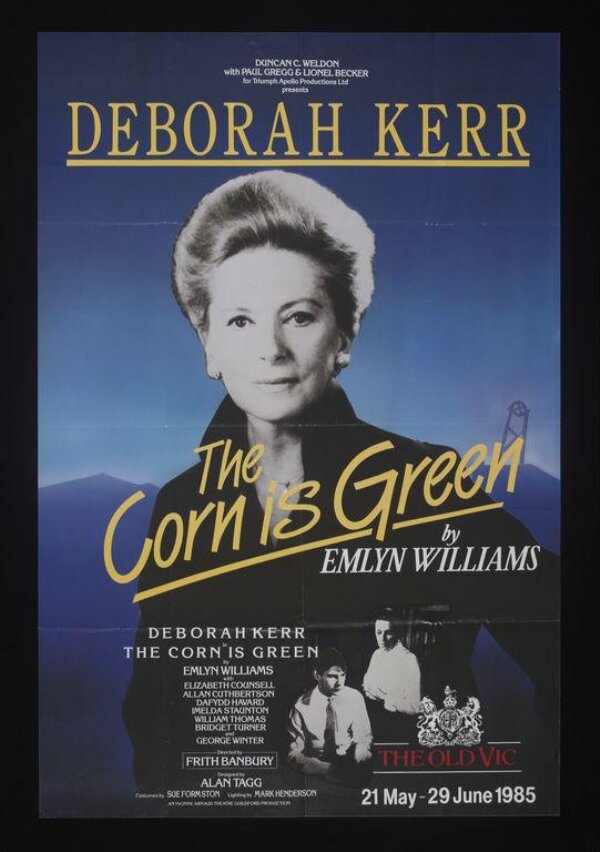

She was honoured by the Cannes Film Festival in 1984, and the following year she made her last feature film, The Assam Garden. In a revival of Emlyn Williams’s The Corn is Green (1985), she portrayed the admirable school-teacher Miss Moffat who recognises the talent in one of her miner pupils, but the run was marred by apparent nerves and fluffing of lines. On television she had particular success with the mini-series A Woman of Substance (1983), sharing with Jenny Seagrove the role of the founder of a department store dynasty.

In 1994 Kerr was finally awarded an honorary Oscar. Elia Kazan, who directed her on stage in Tea and Sympathy and on screen in The Arrangement (1968), said,

Deborah Kerr is a great lady. Let that stand by itself. She is also a fine actress, a joy to work with, devoted, understanding and gifted with a sense of humour. She is outstandingly fair to her fellow performers. She is regally handsome. That’s enough. If I say any more it might embarrass her or swell her head. And I wouldn’t want that.

Tom Vallance

This obituary can also be accessed on-line here.