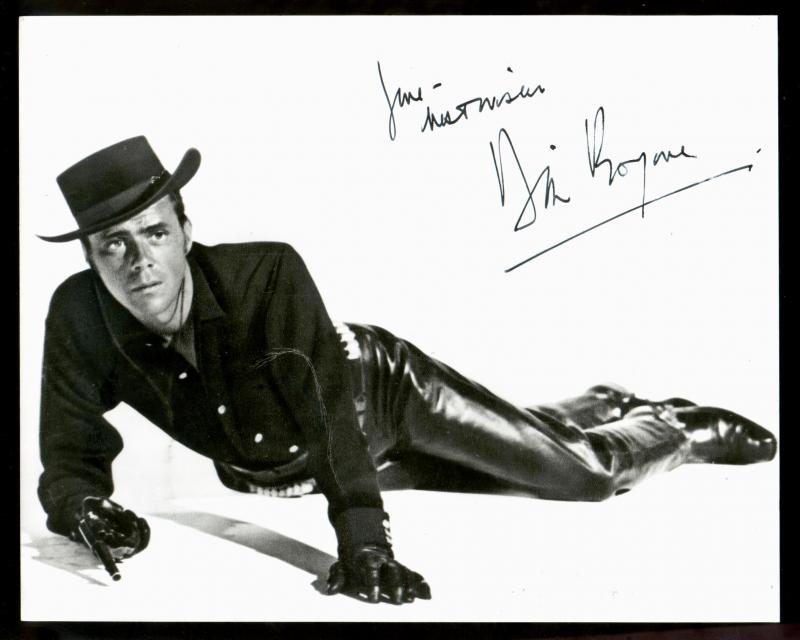

Dirk Bogarde obituary in “The Independent” in 1999.

His “Independent” obituary:

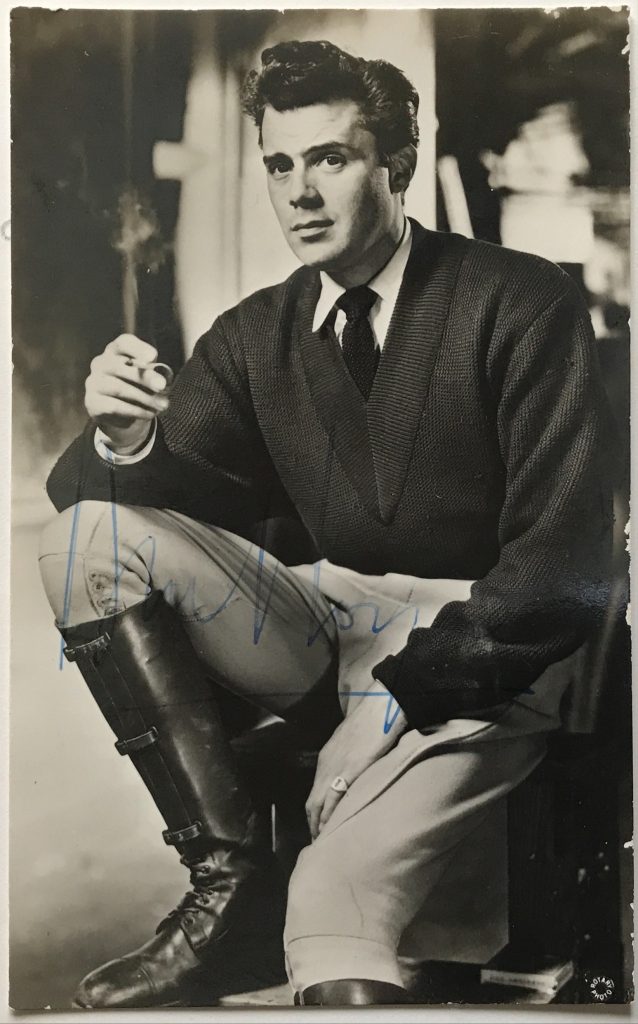

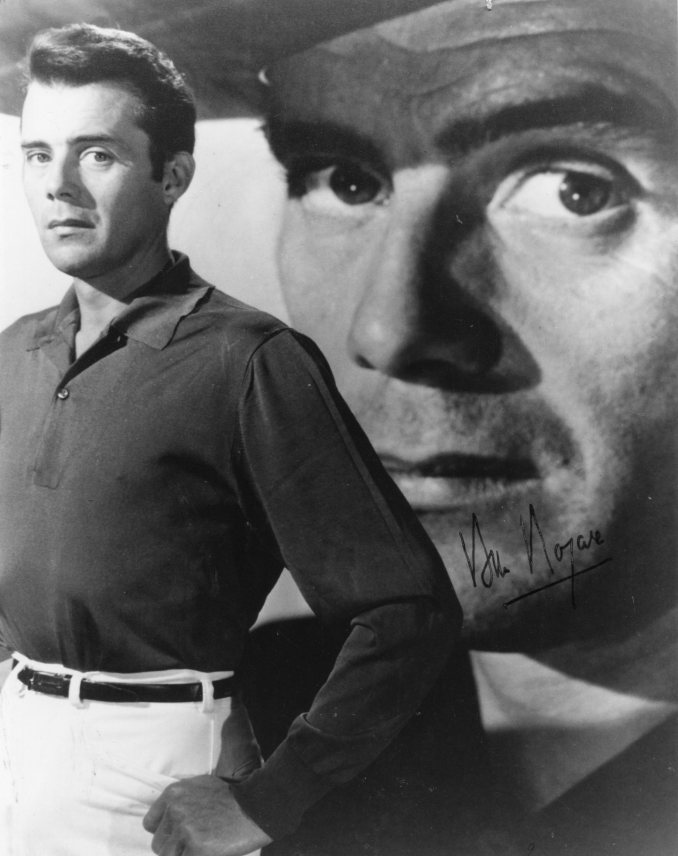

LIKE GARBO before him, Dirk Bogarde mysteriously exceeded the sum of his parts. Many of his 63 films were forever banal, while others initially thrilling and controversial were tamed or stultified by time. In a career spanning almost 60 years he willingly switched disguise, but neither wigs nor breeches, the officer’s khaki nor the doctor’s white coat, could long conceal his limitations of range. When he offered subtlety and suggestiveness instead of versatility those limitations appeared almost a virtue; but with the failure of that exchange in the mid-1970s his acting became almost intolerably arch and repetitive.

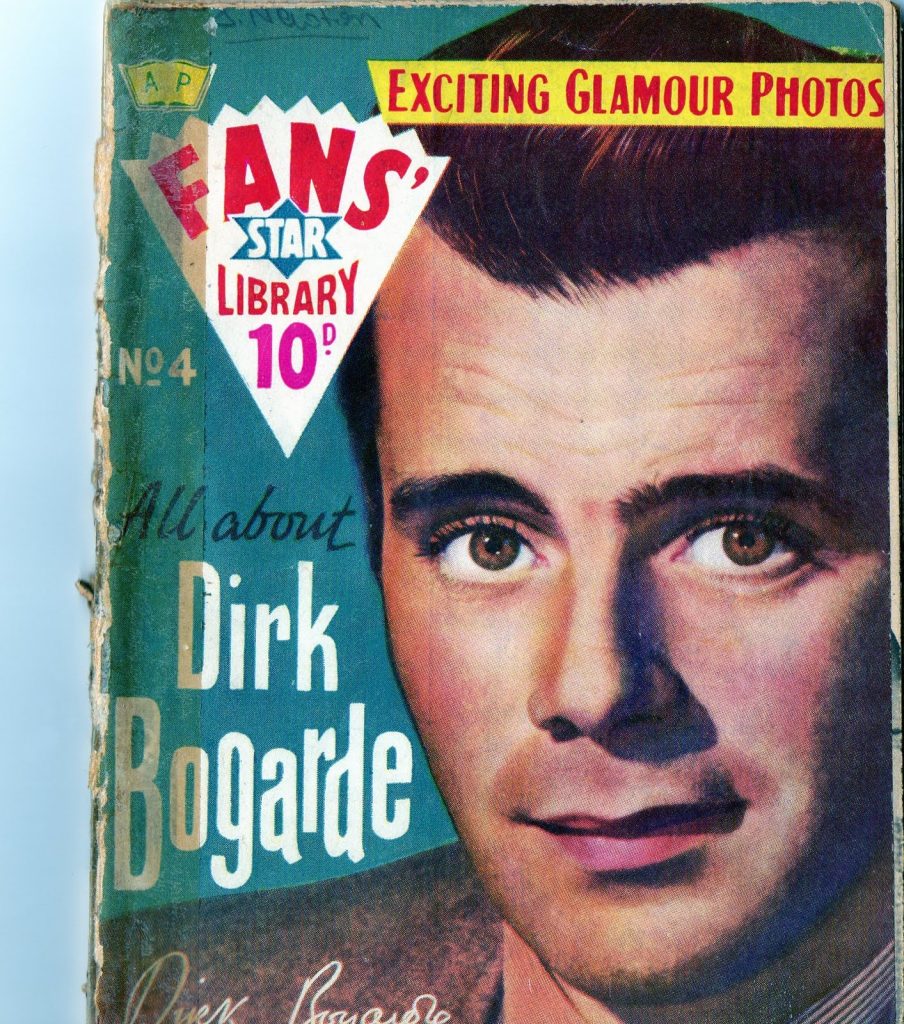

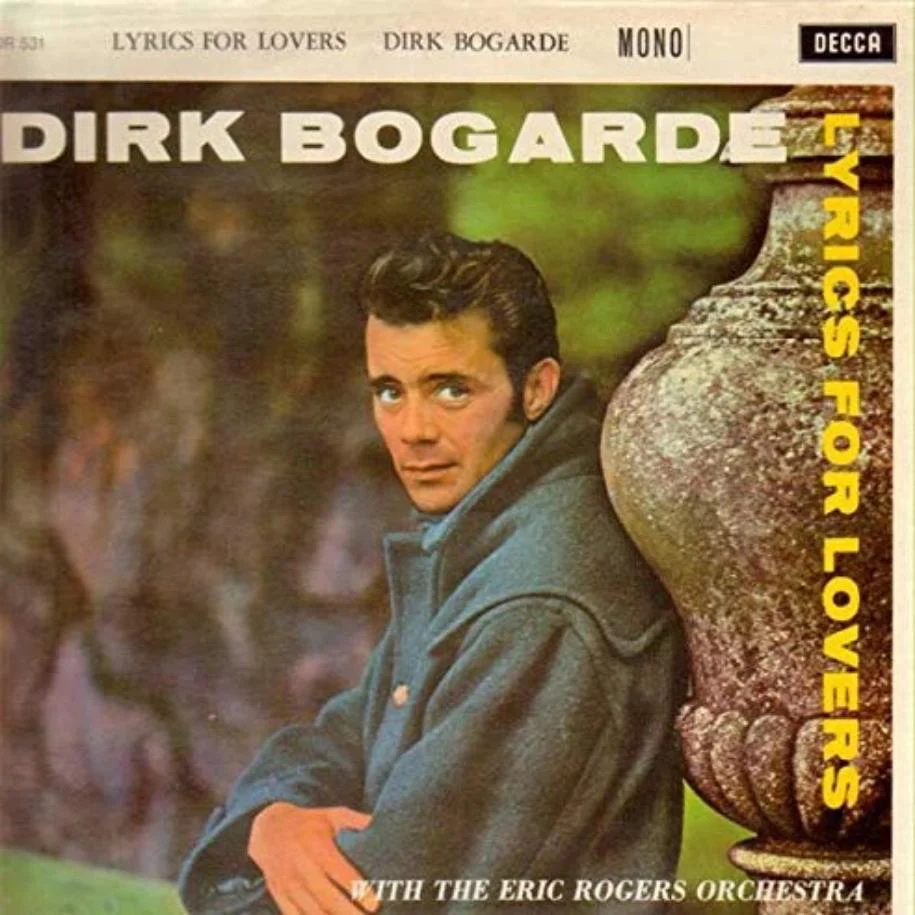

Yet he could never be dismissed – and his stature involved something more than the fact that to critics and colleagues he suggested stylish professionalism, or that in 1955 and 1957 his popularity made him Britain’s principal box-office attraction, or that he rejected formulaic heroism in Hollywood and Pinewood to redeem himself in the European cinema he found more inquisitive.

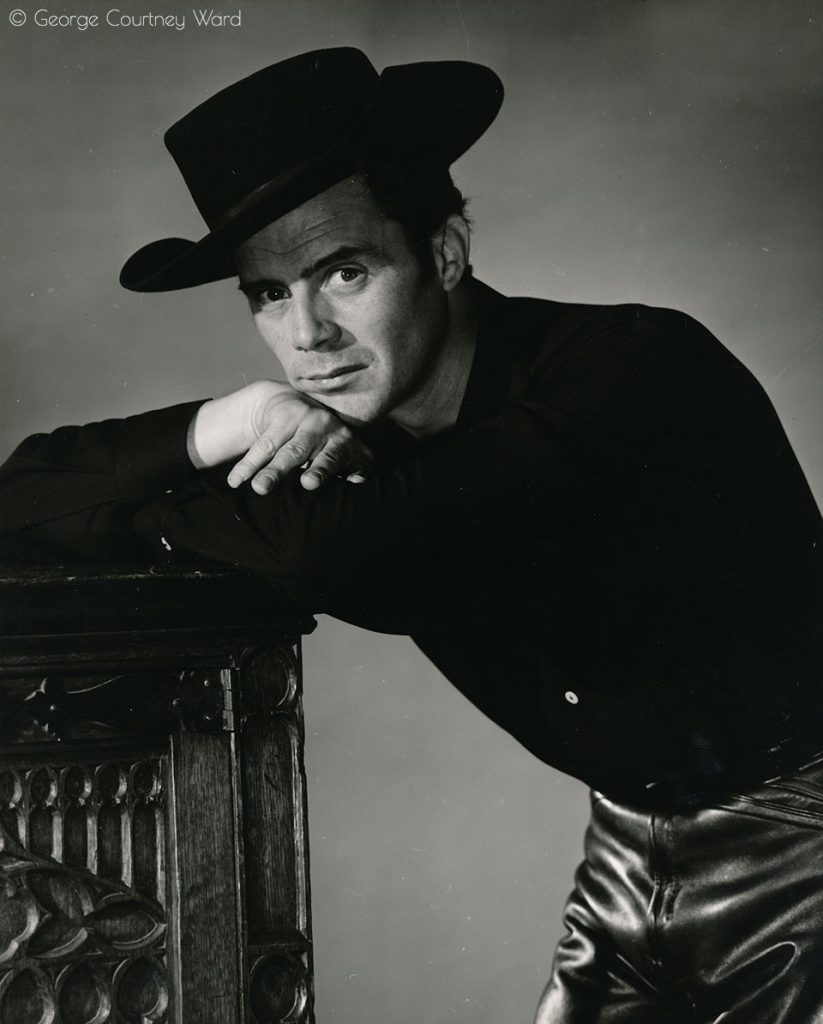

Dirk Bogarde was a major figure because, wherever they were made, his finest films are all somehow about him. He was a great self- portraitist and the screen persona he fashioned, a stylisation of his private being, not only dominated its surroundings but spoke subliminally and powerfully to British audiences about the tensions of the time, about the connivances and cruel respectabilities of England in the Fifties and Sixties.

By the time he renounced acting for writing his numerous renditions of acquiescers, outsiders, self-doubters and repressors of secrets constituted a poetic enquiry into the dramas of pragmatic dishonesty and subterranean emotion and had made Bogarde emblematic, a man who might have been born to play exiles from happiness.

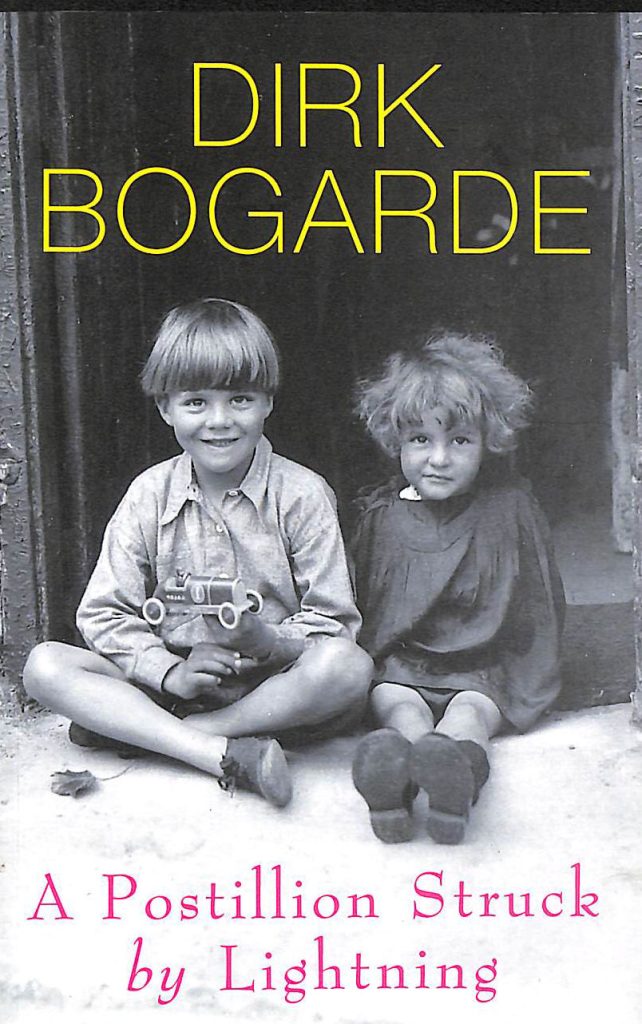

Indeed when he took to writing in his fifties Derek Jules Ulric Niven van den Bogaerde’s first impulse, in A Postillion Struck By Lightning, was to depict his childhood as a lost paradise, only later conceding that despite its contentment he had learnt before adolescence “every lesson needed to get through adult life, from courage, to control, to determination and deceit”.

His Scottish mother, Margaret Niven, daughter of Forrest Niven, actor and painter, was compelled by her husband to abandon acting, despite her Haymarket appearance in Bunty Pulls The Strings and despite an invitation from Hollywood to join the Lasky Players. Her regret was lifelong and she looked to alcohol for the mitigation three children could not always provide. Besides, her half-Dutch husband, art editor of The Times, worked too hard; soon Dirk and sister Elizabeth sought amusement in nursery theatricals.

While still a schoolboy, and perhaps with encouragement from his actress godmother Yvonne Arnaud, Dirk appeared in an amateur production of Alf’s Button and every summer, when the family retreated to a cottage in Sussex, he and his sister animated the enchanted countryside with make-believe.

Innocence, inevitably, was doomed. A new-born brother Gareth usurped attention and Dirk, installed at the Allan Glen’s School in Glasgow, was bullied into chronic self-doubt. Further patchy schooling in London culminated in a course of commercial art at Chelsea Polytechnic, where he was taught by Henry Moore and Graham Sutherland (who later found his features too anodyne to merit portraiture).

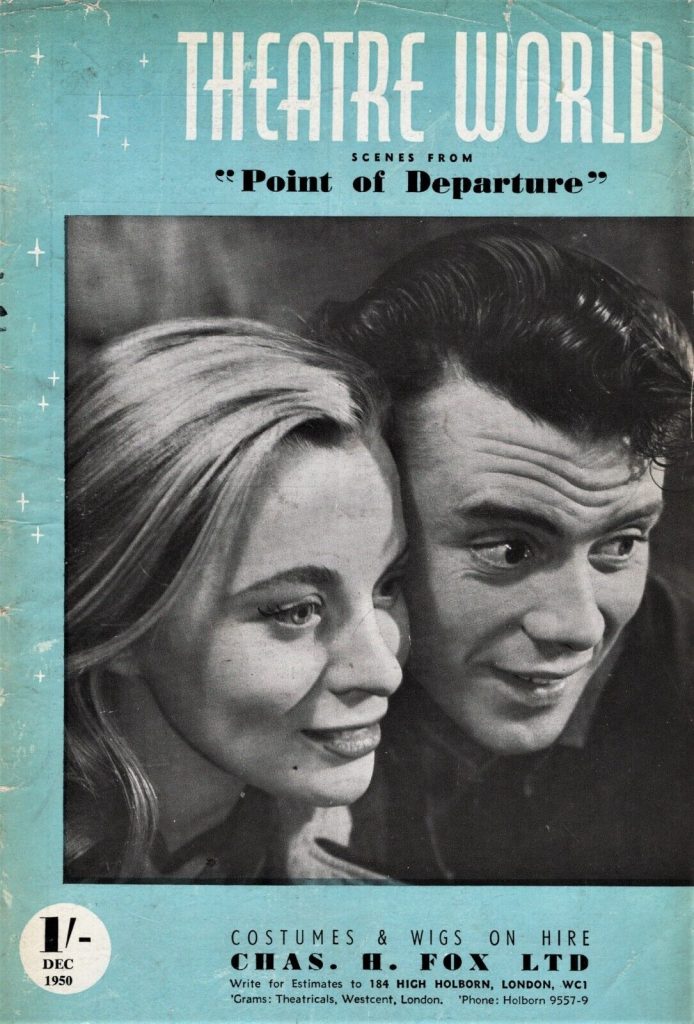

Despite Ulric’s hopes that his son would pursue a career in art or diplomacy Dirk wanted to act: in 1939 he was an extra in the George Formby comedy Come On, George and months later, when he made his West End debut in J.B. Priestley’s Cornelius, The Stage praised his “sulky true-to-life office boy”.

Engagement to the actress Annie Deans quickly failed and following conscription into Ensa he was called to war at Catterick army camp. He proved an inept signaller, but eventually became a major in Intelligence; he was in Normandy for D-Day, was decorated, and demobbed in Singapore. Distinction notwithstanding, military life taught advanced disenchantment: off-duty war paintings (some of which now belong to the Imperial War Museum) helped channel distress but many experiences registered anguish too great for anything but later flippancy. As for witnessing the liberation of Belsen, “We never spoke of it again to anyone”.

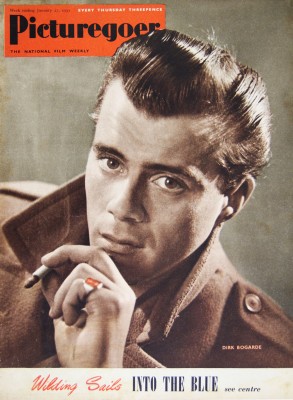

He returned to civilian life without much hope or many credentials, yet within two years he had anglicised his name, acquired a first agent, won Noel Coward’s admiration for his proletarian murderer in Power Without Glory at the New Lindsay Theatre and appeared in a television adaptation of Rope, playing the first of many homosexuals.

Coward urged that the beginner’s destiny lay on stage but events swiftly confounded him. Wessex Films offered Bogarde a part in Esther Waters (1947); then with Stewart Granger’s defection the leading role was thrust upon him; then J. Arthur Rank, which distributed Wessex Films, proffered a contract, despite anxieties about its new recruit’s skinny neck, uneven leg length and asymmetrical head.

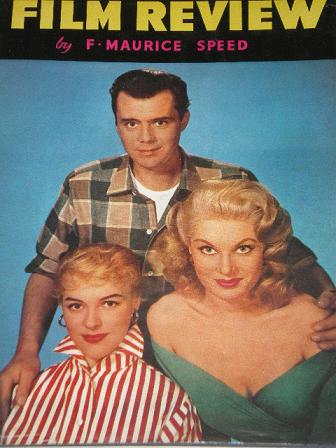

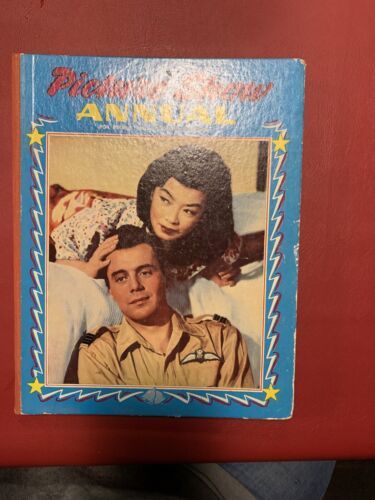

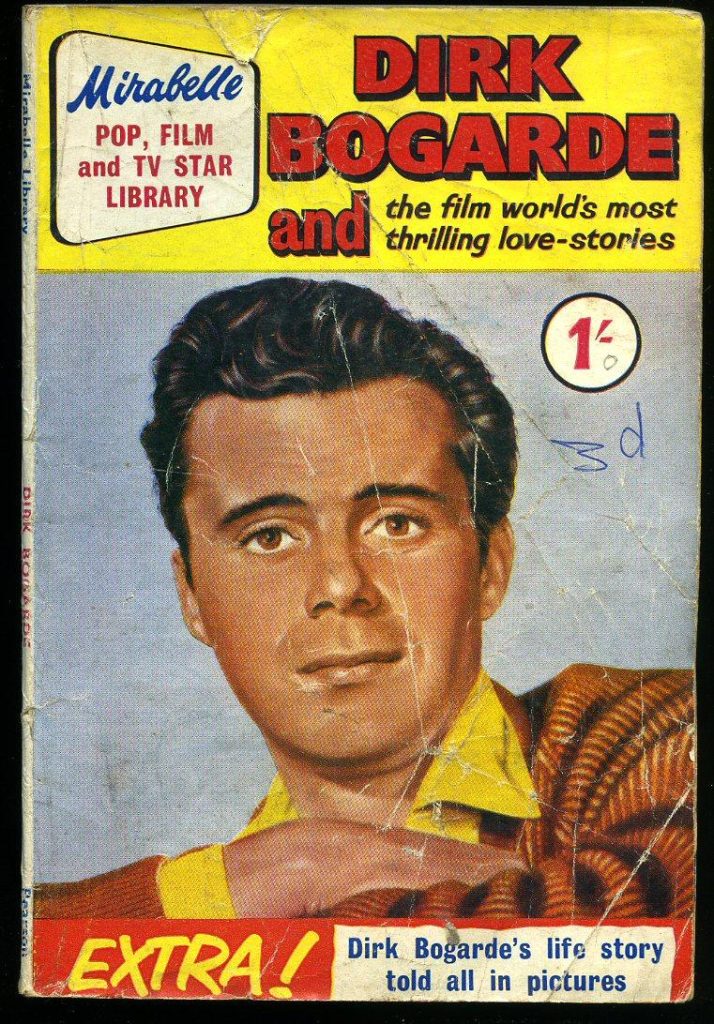

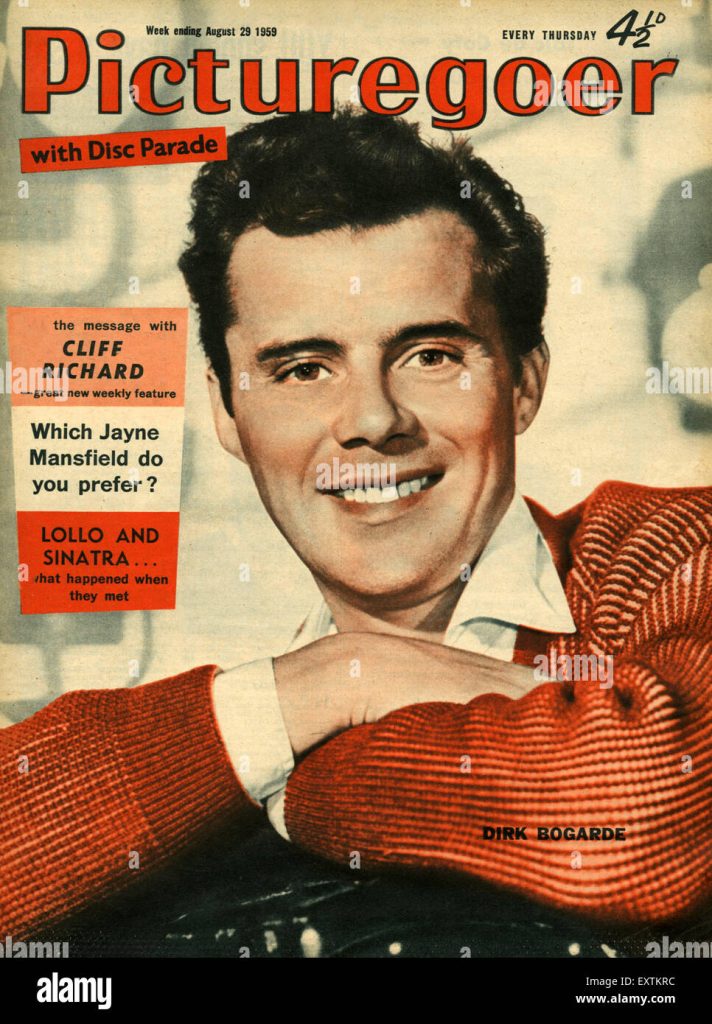

His 14 years with Rank proved a glamorous apprenticeship. Beginning in 1947 on pounds 30 a week, he emerged a decade later as Britain’s principal star: each film gained him about pounds 10,000, his off-set publicity involved the land-owning accessories of dogs, Bentleys and big houses and Rank appointed the actresses he dated.

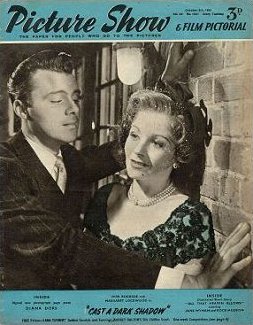

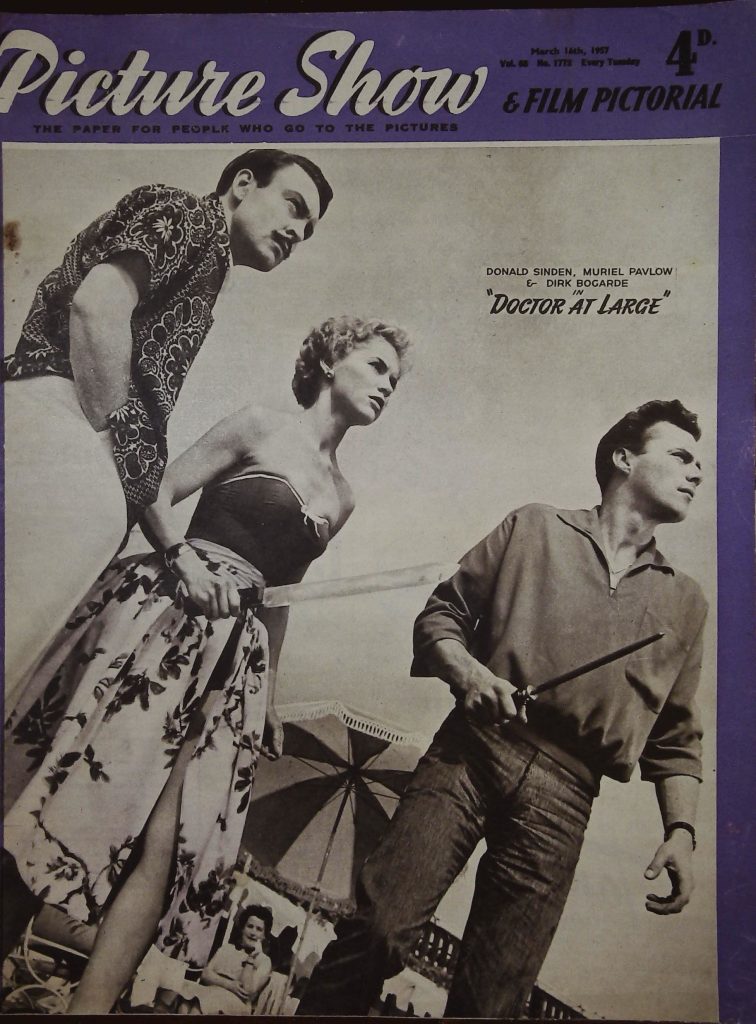

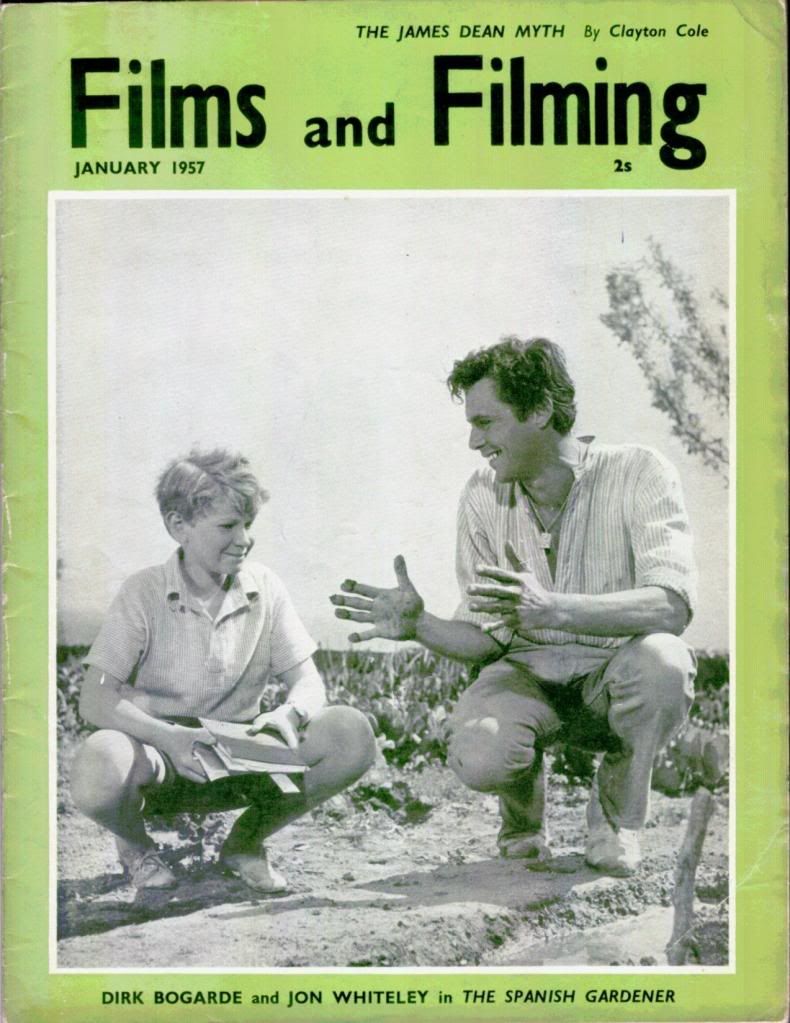

Of the 36 films he made with the studio few merited his or his audience’s attention: The Blue Lamp (1949), paean to the British bobby, made his name; Doctor in the House (1954), based on Richard Gordon’s novels about medical students, his fortune; and Victim (1961) his reputation, as an actor prepared to venture his popularity in a film which at the dawn of the Sixties appeared almost self-destructively controversial and conscientious.

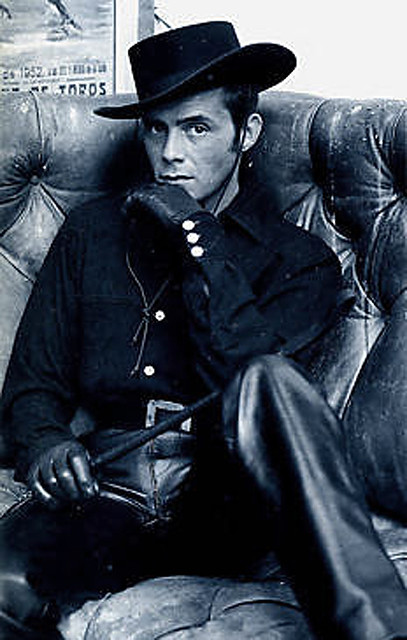

Nevertheless he learnt the technicalities of filming and understood why whole sets rose around his gentler left profile. He developed a confidant intimacy with the camera and enriched every film he made with his exotic prettiness, his thoroughness and his tense, truculent style.

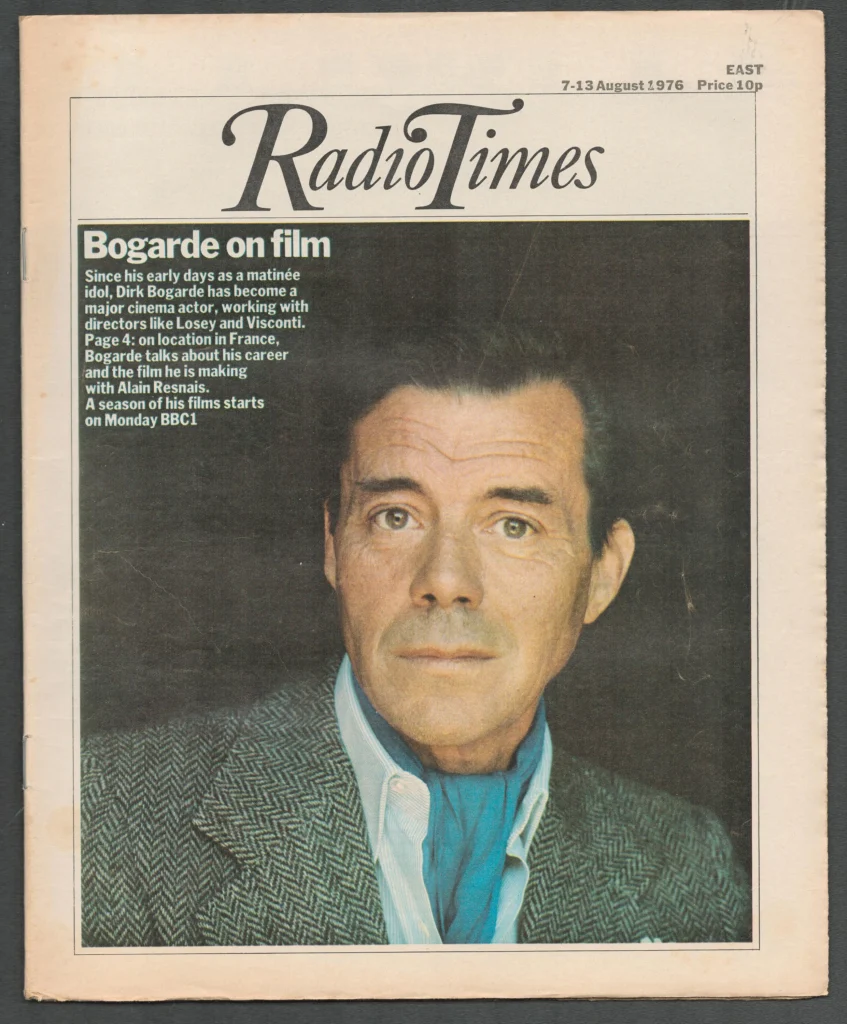

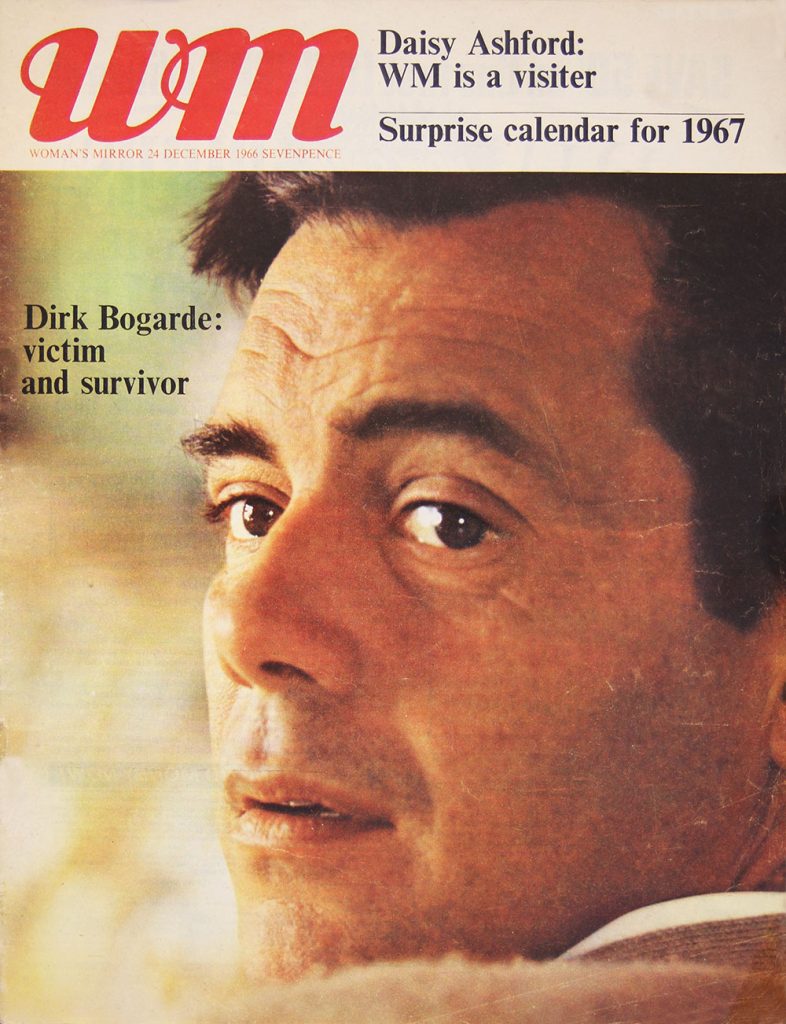

After Victim, which confronted homosexuality as a certainty and exposed the evils of its illegality, there was no returning to studio fantasias. Bogarde left Rank in 1961, and for the next 17 years devoted himself freelance to the films which brought him international fame, films which taxed his sensitivity of interpretation and showed him willing, in his forties and fifties, to address the controversial preoccupations of a youthful and liberal age.

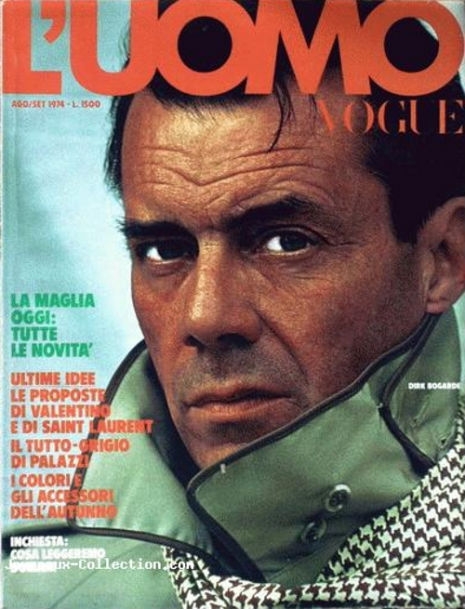

The social allegory of Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963) may now seem dated but Bogarde’s performance (which won him his first British Film Academy Award) retains its stealthy menace. Death in Venice (1971, directed by Luchino Visconti) has its longueurs but Bogarde’s Von Aschenbach remains a virtuoso rendition of almost wordless yearning. For all its flamboyance, The Night Porter (1973) is a determined investigation, structured around Bogarde’s Max, into the passions of sado-masochism.

Yet as his European prestige grew so, despite the direction of Losey, Visconti, Resnais and Fassbinder, did his mannerisms; and his celebrated facial inflexions, which began as disclaimers of involvement and passion, developed into an unwitting but almost declamatory spinsterishness.

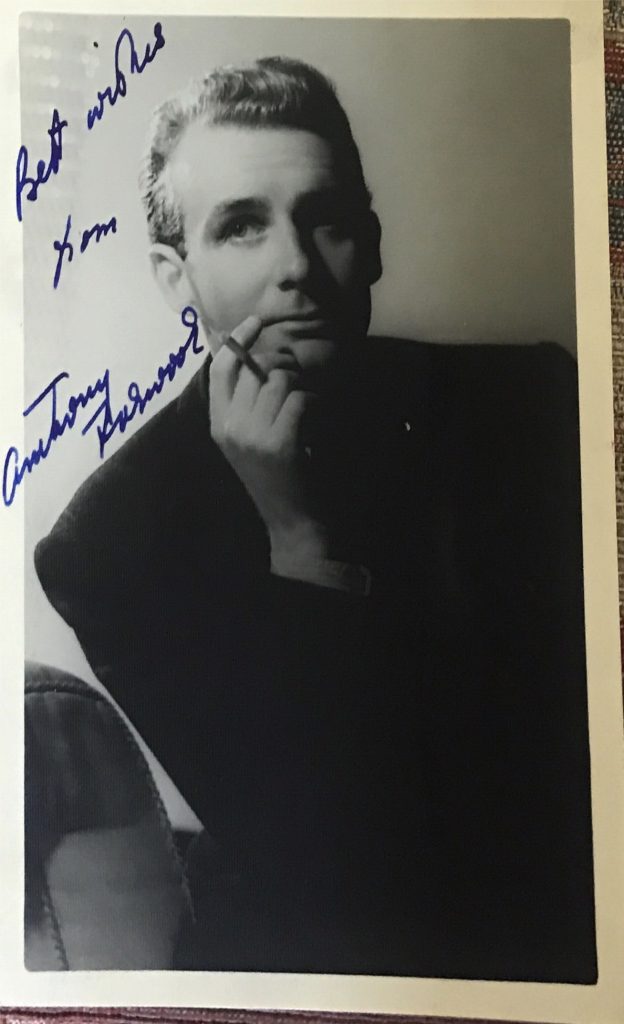

In any case, he was retreating – from England and from film. Along with Anthony Forwood, the former husband of Glynis Johns who became his manager and lifelong companion, he restored a 15th-century farmhouse near Grasse and recreated the paradise of distant Sussex; and in 1977 he began his successful career as an autobiographer and novelist with Postillion, his first volume of memoirs.

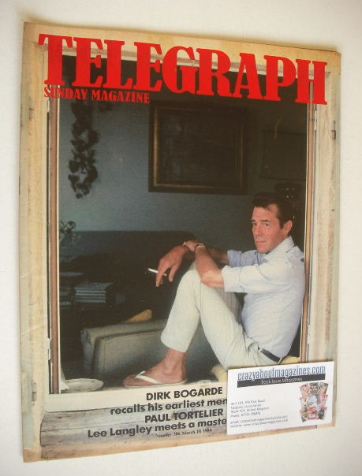

He was retreating also from people. He had never cultivated the common touch, never welcomed fame’s intrusions into privacy; and unscheduled digressions in later interviews revealed with what asperity he manned his fortress. But he was an illusionist by trade and he outmanoeuvred curiosity with dexterity.

His best-selling autobiographies won him a reputation for self- revelation when in fact they camouflage: Postillion (which merits survival) beautifully evokes his childhood, indeed is generous with its harmless secrets and sins; but the sequels, which could have explained the mature Bogarde’s inner workings and should have given some account of Tony Forwood, the most important figure in his life, are in varying degrees thespian anecdotage.

His excursions into the more revealing medium of fiction (inspired by experience) were smooth; but although the slickness of his novels is occasionally animated by accounts of female domination, male narcissism and male prostitution, their author’s true pleasures remained classified.

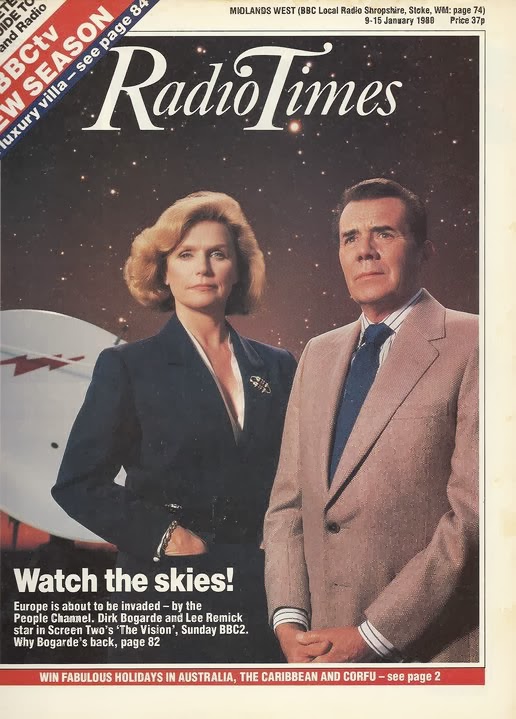

Even as he guarded it, Dirk Bogarde’s neat world crumbled. Having been ill since 1983 Forwood died in 1988, doubly stricken with cancer and Parkinson’s disease. The French house was sacrificed to medical bills and proximity to London hospitals and Bogarde’s last years passed in a flat in Chelsea. Planning ahead, he espoused euthanasia in 1991 and in 1992 he received a knighthood. He reviewed books for The Sunday Telegraph, contributed irritable, anglophobic articles elsewhere and testily reiterated his heterosexuality – but discreetly friends thought him unbearably embittered by Forwood’s death.

It was a grief he could not allow himself to acknowledge, a grief which united with his early and frequently reinterpreted disillusion to lend to his public appearances a great disenchantment. Off-duty, he seemed even more poignant – squeamishly skirting Sloane Square, his hair as black as the dying Von Aschenbach’s, his manner no less fussy, frail and furtive; and Chelsea’s pavements, like Visconti’s Lido, a lonely place for yearning.

Derek Jules Ulric Niven van den Bogaerde (Dirk Bogarde), actor and writer: born 28 March 1921; Kt 1992; died London 8 May 1999.

“The Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

.