“Guardian” obituary by Michael Coveney in 2010:

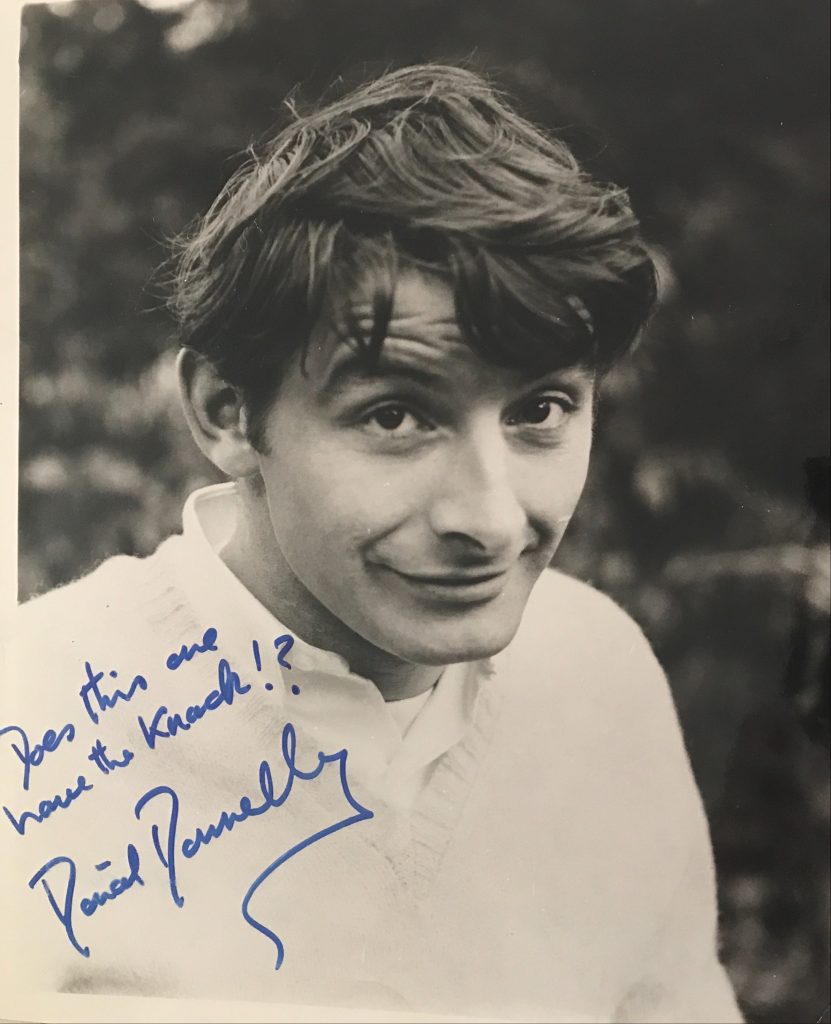

For an actor who worked with two of the greatest movie directors of the last century and appeared in the world premieres of plays by Brian Friel, Ireland’s leading contemporary dramatist, Donal Donnelly, who has died after a long illness, aged 78, was curiously unrecognised. Like so many prominent Irish actors in the diasporas of Hollywood, British television, the Westd and Broadway – all areas he conquered – Donnelly was a great talent and a private citizen, happily married for many years, and always seemed youthful. There was something mischievous, something larkish, about him, too. He twinkled. And he had a big nose. He had long lived in New York, although he died in Chicago, and had started out in Dublin, although born in England.

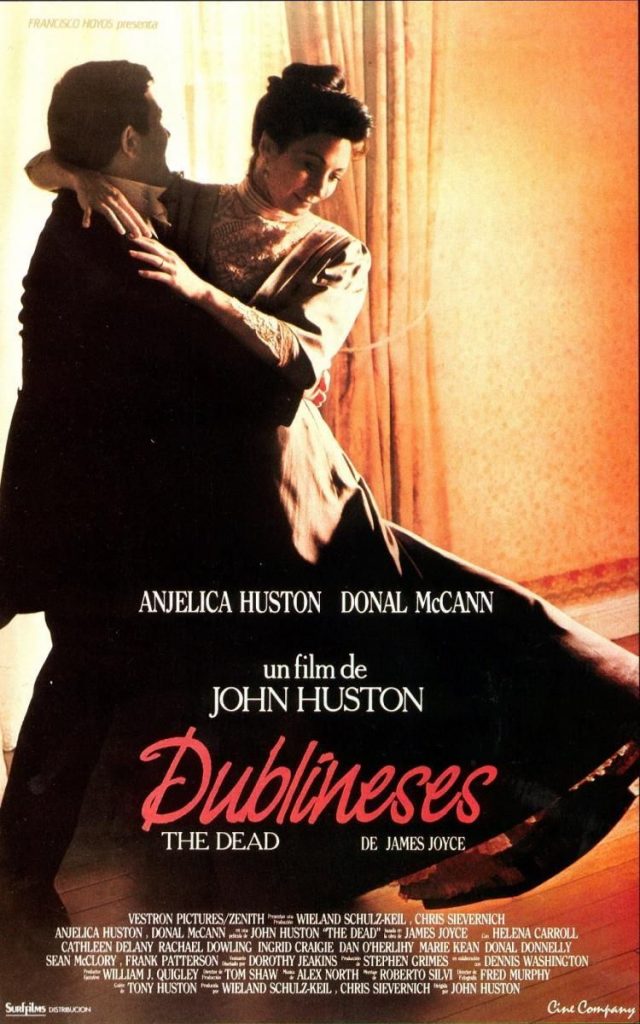

In John Huston’s swansong movie The Dead (1987), the best screen transcription of a James Joyce fiction, he played the drunken party guest Freddy Malins with such wholesome charm, sly wit and nasal authority, that one would never have thought the character himself was a terrible bore. It is a treat of comic timing when Donnelly, having sat patiently through a high-flown debate about the merits of a big-deal production of La Bohème, innocently enquires if anyone’s been to the pantomime at the Gaiety. Set in Dublin in 1904, Huston’s film, possibly the greatest last movie ever made by a director, magically melds today and yesterday in the performances of his daughter Anjelica, Donal McCann and many others.

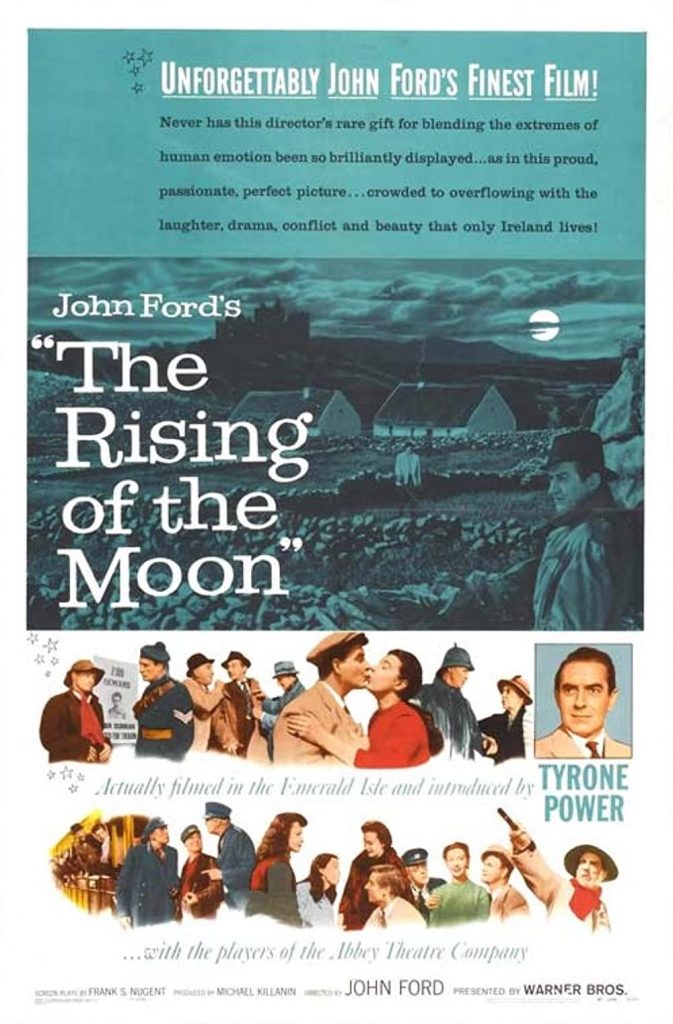

Early in his career, Donnelly brushed with John Ford, another legendary Hollywood director visiting Irish ancestral roots, in The Rising of the Moon (1957), an anthology of three stories by Frank O’Connor, Martin McHugh and Lady Gregory, founder of the Abbey Theatre. Ford was irascible and drunk on the shoot, forcing Donnelly to display his gap teeth to the British crew as evidence and consequence of imperial oppression and the potato famine. Donnelly always said he was considered for a time by Ford to play the lead, Sean O’Casey, in Young Cassidy (1965), but the role went, weirdly, to the Australian Rod Taylor, and Donal made do with a supporting role – literally, since he played a pallbearer. He played a private with a penchant for pigs in Sergei Bondarchuk’s disastrous movie Waterloo (1970), with Rod Steiger as Napoleon Bonaparte. But after that, his film career never really developed, with the possible exceptions of his appearance as a strange archbishop in The Godfather: Part III (1990) and a bemused foster parent entangled in a routine love story in This Is My Father (1999) with James Caan.

Born in Bradford, West Yorkshire, Donnelly was the son of a doctor. The family soon moved to Dublin. He was educated at the Synge Street Christian Brothers school, where he acted in plays with contemporaries such as Milo O’Shea, Eamonn Andrews, Jack MacGowran (with whom he later shared a London flat) and Jimmy FitzSimons, the brother of Maureen O’Hara. He toured with the actor-manager Anew McMaster – an Irish equivalent of Donald Wolfit – so Donnelly was no novice when he made his London debut at the Royal Court in 1959 in Lindsay Anderson’s production of John Arden’s brilliantly provocative anti-military drama, Serjeant Musgrave’s Dance. But his career really took off when he played Christy Mahon, the title role in The Playboy of the Western World, opposite Siobhan McKenna as Pegeen Mike, in the West End in 1960, followed by a lead role in O’Casey’s Red Roses for Me, opposite Leonard Rossiter at the Mermaid Theatre.

He returned to Dublin for the biggest break in his life – Friel’s first play, Philadelphia, Here I Come! at the Gaiety in 1964, presented by the Hilton Edwards and Micheál MacLiammóir partnership of the Gate Theatre, the major artistic rival of the Abbey Theatre, with Edwards directing. Donnelly played the private voice of Gareth O’Donnell (Patrick Bedford was the “public” Gar), a man with a split personality leaving his homeland for America. He and the cast were a huge hit in Dublin and New York. Donnelly later played the sharp-witted cockney agent opposite James Mason’s titanic mystic in the world premiere of Friel’s masterpiece Faith Healer (1979) in New York, and the old missionary priest Jack in the Broadway premiere of Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa.

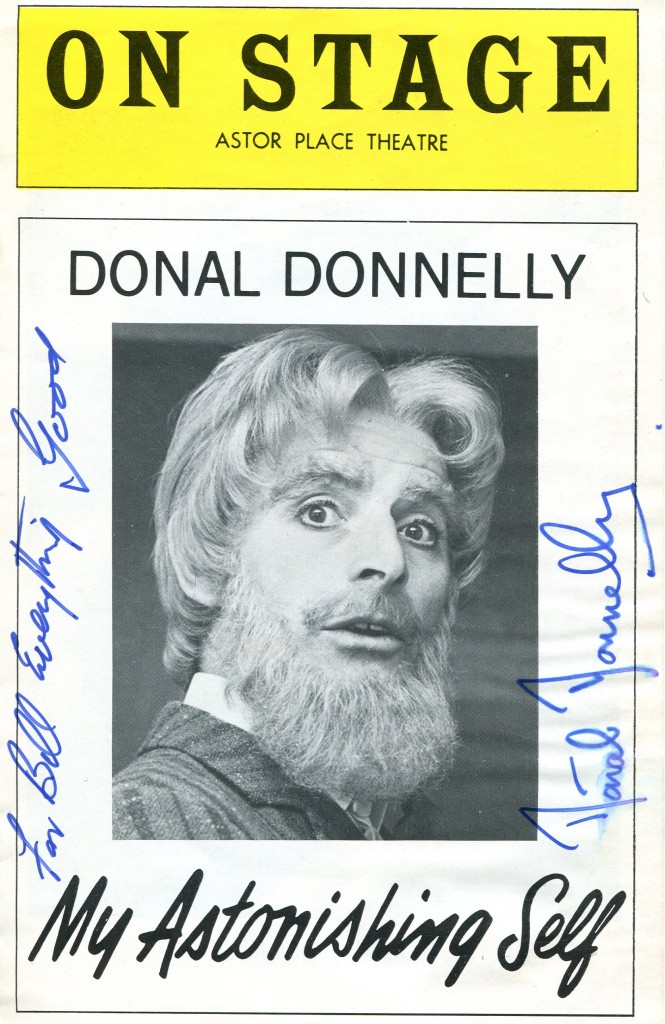

He was perhaps best known in Britain as the struggling songwriter Matthew Browne in the television sitcom Yes, Honestly (1976-77), co-starring Liza Goddard, but he will be remembered, too, as a splendid impersonator of George Bernard Shaw in his one-man show My Astonishing Self, which he introduced at the Dublin festival in 1976, and also in Jerome Kilty’s correspondence “drama” with Ellen Terry, Dear Liar, with which he bowed out on Broadway in 1999. Donnelly, much loved by his peers and contemporaries in the Dublin theatre – although he was never associated with the Abbey – is survived by his wife, Patsy, and their two sons.

• Donal Donnelly, actor, born 6 July 1931; died 4 January 2010

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

.

Dictionary of Irish biography:

Donnelly, Donal (1931–2010), actor, was born on 6 July 1931 in Bradford, Yorkshire, the third son among seven children of James Donnelly (d. 1964), a general practitioner, and his wife Nora (née O’Connor). Dr Donnelly was originally from Tyrone and Nora from Kerry, and the family moved to Ireland when Donal was five. They lived in Victoria Road, Rathgar, Dublin, and Donal was sent to Synge Street CBS, where an inspiring teacher, Frank MacManus (qv), encouraged the boys to appreciate drama and put on their own plays. The school’s alumni included figures such as Jack MacGowran (qv), Eamonn Andrews (qv) and Milo O’Shea(qv). Donal appeared in some school plays with O’Shea, and they became friends.

Donnelly worked for a short time in a saddlery and outfitters’ business, but devoted most of his spare time to amateur drama after joining the Bernadette Players from Rathmines, first appearing with them in a satirical review in 1950. Edward Pakenham (qv), Lord Longford, gave him a job as an assistant stage manager in the Gate Theatre, and he first acted at the Gate in 1952. After that, he opted for an acting career, spent some time touring in Ireland with the actor-manager Anew McMaster (qv), and joined the Dublin Globe Theatre Company, with which he appeared in a number of avant-garde productions in a room above the gas company showroom in Dún Laoghaire.

In 1957 he appeared with Jack MacGowran in ‘The shadow of a gunman’ at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, London, and then in other plays in London. He achieved considerable success in several productions of ‘The playboy of the western world’ (by John Millington Synge (qv)), as Christy Mahon; one critic later remembered him as the best Christy he had ever seen, in a 1960 West End performance opposite Siobhán McKenna (qv) as Pegeen Mike. Donnelly followed this with the lead role in ‘Red roses for me’, by Sean O’Casey (qv), playing opposite Leonard Rossiter at the Mermaid Theatre in London.

Donnelly was lightly built, with great energy and vitality, and a notable ability to inhabit characters fully. A natural mischievousness enabled him to play comedy with ease, but he was immensely versatile and could give a vulnerable or sinister edge to his roles as required. From the mid 1950s onwards, he was omnipresent on the stage, both in Dublin and London. A major triumph was his role as Gar Private in the premiere production of ‘Philadelphia, here I come!’, by Brian Friel (1929–2015), in 1964 at the Gaiety, Dublin. He got equally good reviews in New York when the play was produced on Broadway in 1966. He was nominated for a Tony award jointly with Patrick Bedford, who played Gar Public. Donnelly appeared to acclaim in other Friel plays, notably in ‘Faith healer’ (1979; world premiere in New York), and in the Broadway premieres of ‘Dancing at Lughnasa’ (1991), defining for American audiences the role of the old missionary priest, and ‘Translations’ (1995). In 1969 at Dublin’s Olympia Theatre, Donnelly directed his first play, another by Friel, ‘The Mundy scheme’.

He became something of an expert on George Bernard Shaw (qv), collecting Shaw memorabilia and appearing during the 1970s in a number of productions in Dublin, Boston and Hong Kong of a one-man show, ‘My astonishing self’, that he wrote based on the dramatist’s life and writings, and appearing in the play as Shaw in youth and also in fully-bearded old age.

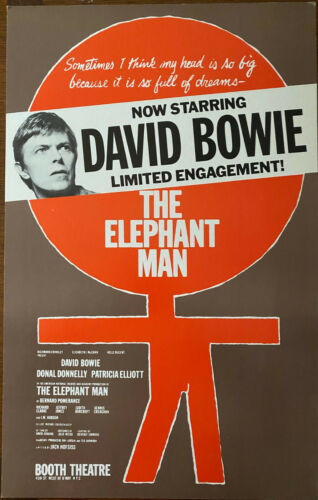

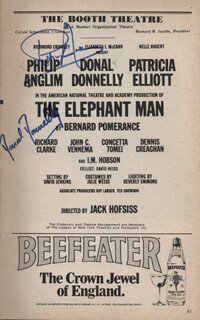

Though Donnelly was most familiar in plays by Irish authors, especially Friel, O’Casey and Samuel Beckett (qv), his versatility enabled him to appear in a wide variety of roles. From 1973, he appeared 860 times in Anthony Shaffer’s ‘Sleuth’ in Dublin, London and New York, including a record-breaking run in the Olympia, playing opposite his close friend T. P. McKenna (qv). Another notable role was as the surgeon Sir Frederick Treves as a replacement actor during the two-year Broadway run of Bernard Pomerance’s ‘The Elephant Man’, opposite David Bowie’s John Merrick (1980–81). In the Broadway production of Peter Nichols’s ‘A day in the death of Joe Egg’, Donnelly replaced Albert Finney in April 1968; his characterisation of a father struggling with a child with disabilities was described as a ‘compassionate vaudeville of despair’ (New York magazine, 6 May 1968).

Donnelly had a small part in The rising of the moon (1957; dir. John Ford (qv)), and another in the first film made in Ardmore Studios, Bray, Michael Anderson’s Shake hands with the devil (1959), which starred James Cagney. Donnelly claimed that Ford had considered him for the lead role in Young Cassidy (1965), a biographical drama based on the life of Sean O’Casey, but eventually he had to make do with a supporting role as a hearseman. He was successful with Rita Tushingham and Michael Crawford in the risqué British comedy, The knack … and how to get it (1965), directed by Richard Lester, which won the Palme d’or at the Cannes film festival. Modest and unassuming, Donnelly saw himself primarily as a stage actor and had little interest in being a film star, but had several other film roles, including a notable part in The godfather: part 3 (1990) as the shifty, chain-smoking Archbishop Gilday in charge of the Vatican bank. He disliked the long periods of waiting about involved in film-making, and spent three trying months in the Ukraine for a small part as an Irish soldier in a the Soviet–Italian epic Waterloo (1970). Perhaps his most successful film role was as the drunken, sentimental Freddie Malins in The dead (1987), an acclaimed version of the story by James Joyce (qv) and the last film made by John Huston (qv). Donnelly’s charm and conviction redeems his character from the annoying mediocrity suggested in the story.

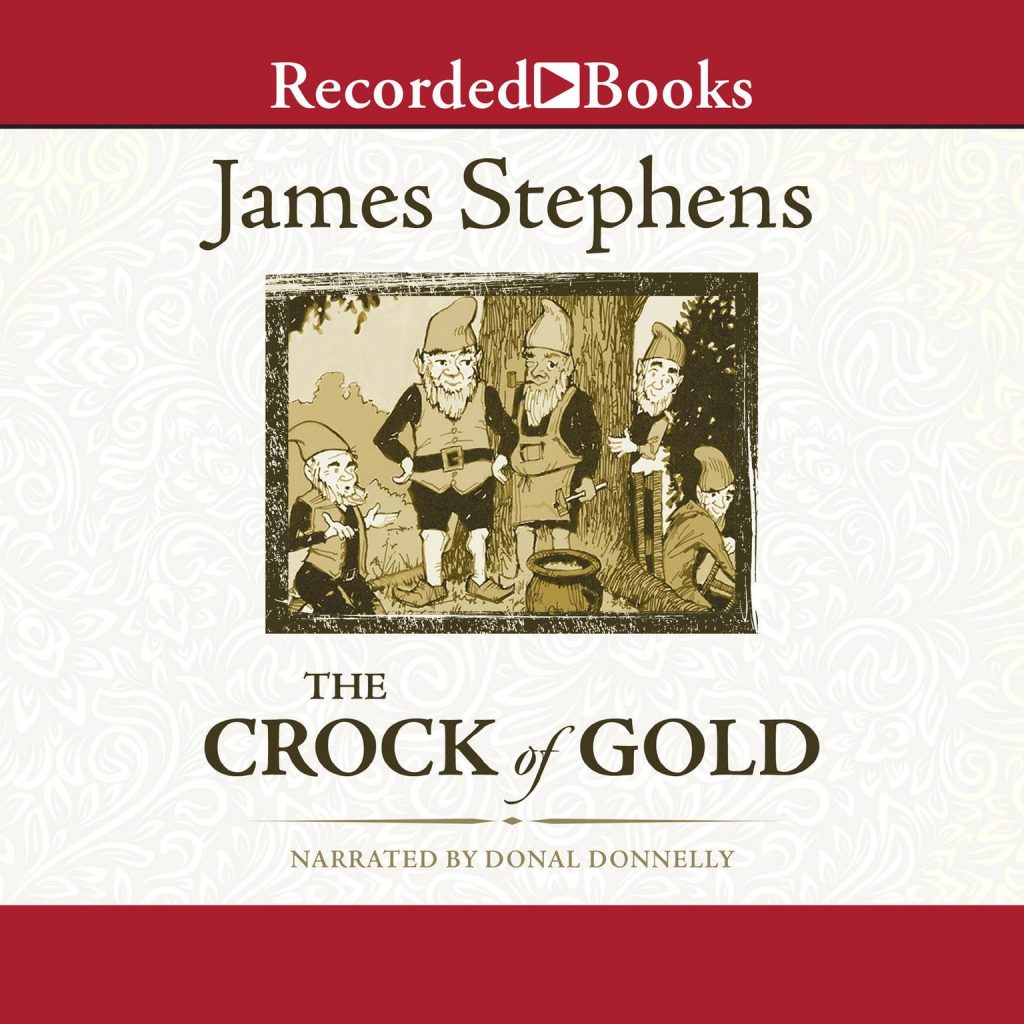

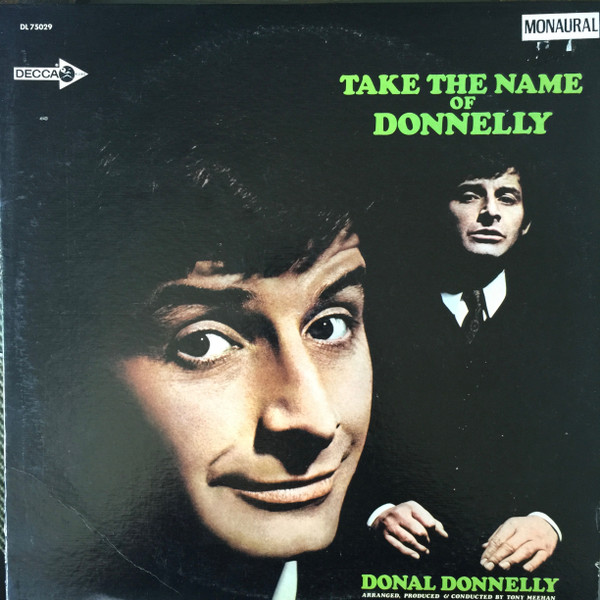

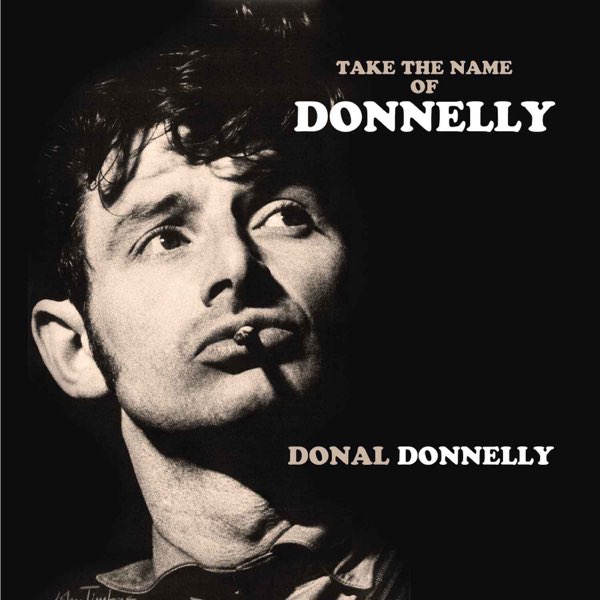

Donnelly kept busy in between theatrical appearances. He appeared in widely varying television programmes in Britain and America, including Z cars, the British sitcom Yes, honestly (1976–7), and the American crime series Law and order, but turned down the lucrative option of a regular part in Z cars to pursue more varied roles. Always prepared to try something new, in 1968 he collaborated with Tony Meehan (1943–2005), former drummer with the Shadows and, like Donnelly, born in England to Irish parents, on the music album Take the name of Donnelly, in which they explored traditional Irish songs. The following year Donnelly released the single ‘Dream things that never were’, which he wrote after the assassination of Robert Kennedy, and performed at a St Patrick’s Day festival show in the Royal Albert Hall, London. His protean and expressive voice made him an ideal reader for audiobooks, and he made at least thirteen such recordings, which ranged from Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio (1991) to a forty-two-hour unabridged version of Joyce’s Ulysses (1995).

On 6 June 1964 he married Patricia (‘Patsy’) Porter, a dancer from Yorkshire whom he met on a production of ‘Finian’s rainbow’ in London. As Donnelly’s career on Broadway took off, he and his family moved to America and lived in Westport, Connecticut, from 1979 to 2008. They experienced a tragic loss when their only daughter, Maryanne, aged 21, was killed in a riding accident. Donal Donnelly, who had been a heavy smoker all his life, died of lung cancer on 4 January 2010 in hospital in Chicago, where he had spent his last years, close to his two sons, Jonathan and Damian; he was survived by them and his wife (d. 2013). A brother, Michael Donnelly, was a Fianna Fáil senator and councillor, and lord mayor of Dublin (1990–91).

by Pete Stampede

Dark-haired, sharp-featured and with a (shall we say) generous-sized nose, Donal Donnelly is primarily a man of the theatre, coming into the business during a rich period in Irish drama, and later extending into Britain, America and other media. For reasons too complicated to go into, he was actually born in Bradford, in Yorkshire in the North of England (in 1931); it hardly makes him alone among Irish actors though, it’s amazing how many were actually born in Britain (and for years, the whisper has been that Peter O’Toole was born in Yorkshire too, not Connemara as is usually claimed). Donnelly was raised in County Tyrone, and by the 1950’s had gained experience at both of Dublin’s premier theatres, the Abbey, which W.B. Yeats had been involved with the founding of and which made a policy of presenting plays set in and reflecting Ireland, and the Gate, founded later by actor-directors Micheal MacLiammoir and Hilton Edwards (both actually English, but let’s not go into that), whose brief was more internationalist, although they would later promote an outstanding native playwright in Brian Friel.

Breaking into films around this time, Donnelly got to work for the legendary John Ford in The Rising Of The Moon (1957), a trilogy of tales largely cast from the Abbey ensemble, also including Jack MacGowran. However, interviewed for a recent biography, Print The Legend; The Life And Times Of John Ford by Scott Eyman, Donnelly recalled that the director was by now more than slightly irascible and reliant on alcohol, and insisting on taunting the British crew on the film; on noticing Donnelly had a gap in his teeth, Ford instructed him to display it to the crew and tell them they were directly responsible, as a result of the Potato Famine! “Amazing bull——”, the actor remembered. He went on to state that Ford had considered him for the lead in a long-planned biopic of Sean O’Casey; however, he only had a supporting role in the resulting Young Cassidy (1965), which was in any case fictionalised as the title suggests, completed by leading cinematographer Jack Cardiff after Ford was taken ill, and starred Australia’s own Rod Taylor, possibly the least convincing playwright on celluloid. Similarly perhaps, Shake Hands With The Devil (1959), an IRA-themed drama set in the 1930’s, had James Cagney heading a curious mix of American and British actors in the leads, with the likes of Donnelly, Richard Harris, Cyril Cusack, Ray McAnally and Noel Purcell—from “A Surfeit of H2O” reduced to supporting roles.

Coming to Britain (where he shared a flat with Jack MacGowran for a while), Donnelly can be spotted in the biased if entertaining I’m All Right Jack (1959) as one of shop steward Peter Sellers’ sheep-like acolytes, along with Victor Maddern—seen in “The Thirteenth Hole“—Cardew Robinson and bit-part king Sam Kydd, unwillingly welcoming upper-class twit Ian Carmichael to the workforce. His best film role was probably in Dick Lester’s The Knack… And How To Get It (1965), as a mate of irritating weed Michael Crawford and cockney Casanova Ray Brooks (seen in “Noon Doomsday“); this was well-praised at the time, although Lester’s self-consciously wacky comic devices and the rather sexist attitudes throughout have definitely dated it, the best thing was John Barry’s music (the CD is playing as I write this)—would any 60’s diehards want to kill me if I say Help! is probably Lester’s best film, better than A Hard Day’s Night? Donnelly also supported in The Mind Of Mr. Soames (1970), a little-seen fantasy with Terence Stamp as a savant and Robert Vaughn as a doctor, and in Sergei Bondarchuk’s commercially disastrous but at least unarguably epic-scale Waterloo (1970), with Rod Steiger as Napoleon, and Donnelly as a private with a fondness for pigs.

On the London stage, he did Sean O’Casey’s Red Roses For Me at Bernard Miles’ Mermaid Theatre in 1962, alongside Leonard Rossiter; there’s a picture from this, showing both of them, at the Rossiter personal site. “Dead On Course” was one of Donnelly’s first sightings on British TV. It was followed by THE Sentimental Agent, “May The Saints Preserve Us” (ATV/ITC, 1963), one of the earliest and least-known ITC series, here with Carol Cleveland also guesting, as a Texan heiress who’s taken a fancy to an Irish castle; Thirty-Minute Theatre, “Application Form” (BBC, 1965), with Denholm Elliott, one of the then-constant anthology series; Department S, “Les Fleurs de Mal” (ATV/ITC, 1969), as a gangster’s intended target, when Peter Wyngarde and chums are baffled by a shoot-out over the flowers of the title—and despite that title, it was partly set in Italy; and the well-rated fantasy anthology Out Of The Unknown, “Get Off My Cloud” (BBC, 1969), starring Peter Jeffrey, for once not as a diabolical mastermind, as an SF writer who suffers a major breakdown and whose thoughts become telepathically linked to Donnelly, playing “the most level-headed person he knows”, a sports journalist. This was made in colour, but has since been wiped (judging by publicity photos of the time, both actors were required to wear some pretty silly costumes).

In the middle of all this, Donnelly returned to Dublin for Brian Friel’s first stage play Philadelphia, Here I Come!, first staged at the Gaiety Theatre in 1964, with Hilton Edwards directing. The character of a young Irishman on the eve of his emigration to the US was split into two; Patrick Bedford, an actor who was groomed by MacLiammoir and Edwards to follow in their footsteps, but didn’t quite, played the man’s public face, all optimistic about starting a new life, while Donnelly was the “Private Gar”, the side of him that sentimentally and conservatively is terrified to break away, a role he reputedly gave a slyly malicious charm to. Friel’s examination of national character and contradiction was enthusiastically received by critics and audiences; still with Donnelly and Bedford in the leads, it ran for 326 performances on Broadway in 1966, gaining Donnelly a Tony nomination for Best Actor in a Play, with a West End production following in 1967. Later, Friel’s Faith Healer, which had its premiere on Broadway in 1979 and starred James Mason, in a rare stage excursion in the title role, featured Donnelly as the unworldly sage’s sharp-witted, exploitative agent. Interestingly, Friel’s stage directions specify that this role must be played “in the Cockney dialect.” More recently, a Boston revival of Friel’s Translations, in 1995 (which Ray McAnally, again, had starred in the original production of), saw Donnelly as a lovable, incorrigible old drunk called Jimmy Jack.

Donnelly’s most visible mainstream role was in a British sitcom, Yes, Honestly (LWT, 1976-77) a follow-on from No, Honestly which had starred real-life husband and wife John Alderton and Pauline Collins. This had Donnelly as a largely unsuccessful songwriter called Matt Browne (where would British sitcoms be without puns!), partnered by perky blonde sitcom regular Liza Goddard; co-writer Terence Brady had, in a former life, appeared in “Fog“. After years on stage, increasingly in the US, Donnelly made a sardonic contribution to John Huston’s last film The Dead (1987), as one of the party guests in this finely measured adaptation of the last story in James Joyce’s Dubliners; this had a largely Irish cast, but the interiors were actually shot in California, with Karel Reisz on standby to direct in case Huston became too ill. Surprisingly perhaps, Donnelly, by now grey-haired and looking somewhat professorial, turned up in Francis Ford Coppola’s delayed sequel, The Godfather Part III (1990), playing a less than saintly Archbishop; however, Coppola in his early years was a big fan of Dick Lester’s, and so had probably seen Donnelly in The Knack.

Occasional guest roles on American TV have included Spenser; For Hire, “One if by Land, Two if by Sea” (ABC/Warner Bros., 1986), and Law And Order, “The Troubles” (NBC/Universal, 1991), unfortunately inevitably cast in an IRA-themed episode, in a scene where a fundraising party is being held for a villain the cops are holding. His more recent films, however, have generally been back in Ireland; Words Upon The Window Pane (1994), from a one-act play by W.B. Yeats; Korea (1995), in what sounds like a very strong role as an angry father, but which doesn’t seem to have been shown outside of film festivals; This Is My Father (1998), as a bemused foster father in what was basically a straightforward Irish love story, but weakened by an unnecessary modern-day US framing with James Caan; and Love and Rage (1998), with that star of the 80’s Greta Scacchi, which (like most of her post-80’s films) has had trouble getting released. He has added recitals and performing Irish songs to his stage work, which has also included a one-man show as George Bernard Shaw, My Astonishing Self, and still for new Irish writers, the American premiere of Martin McDonagh’s The Cripple Of Inishmaan, in 1998. He played Shaw again in Dear Liar, a revival of a 1960 two-hander drawn from Shaw’s correspondence with Mrs Patrick Campbell, at the Irish Repertory Theater on Broadway in 1999. (Years earlier, there had been a BBC TV version of this in the mid-60’s, with James Maxwell as GBS.) Donnelly has voiced more than a few talking books on audio tape, including full versions of Joyce’s Ulysses and Dubliners, recently also participating in a multi-voice version of the latter, with a different reader for each chapter. On the whole, he’s done very well for himself, considering that, in the 60’s at least, he had to labour under the considerable drawback of looking rather like me.