Gabrielle Drake is a very talented and attractive actress who starred in some of the more popular televsion series in Britain in the 70’s ioncluding “The Brothers”. She was born in India in 1944 and lived in other countries in the East before moving to England. Her film credits include is “Connecting Rooms” with Bette Davis, “There’s a Girl in my Soup” with Peter Sellers, Goldie Hawn and Diana Dors and “The Steal”. Recently she has appeared on television as the mother of Lynley in “The Inspector Lynley Mysteries”. She is the sister of the late cult songwriter and singer Nick Drake.

“Telegraph” interview with Gabrielle Drake from 2004:

“Wikipedia” entry

Drake was born in Lahore, British India, the daughter of Rodney Drake and amateur songwriter Molly Drake. Her father was an engineer working for the Bombay Burmah Trading Corporation. As a child she lived in several Far Eastern countries. In 1942 her family had to flee Burma for Britain to escape advancing Japanese forces. She later commented that,

Until then, life was fairly easy out east. There were lots of servants … not that I remember having a spoilt childhood. Then suddenly we were back in England and in the grips of rationing. And yet, we were lucky in a way. We came back with my nanny who knew far more about England than mummy did. I remember the two of them standing over the Aga with a recipe book trying to work out how to roast beef, that sort of thing

On the ship travelling to Britain she appeared in children’s theatrical productions, later saying of herself “I was a dreadful exhibitionist.”[2] She attended Edgbaston College for Girls in Birmingham, Wycombe Abbey School, Buckinghamshire and the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) in London. She has had a long stage career beginning in the mid-1960s, and has regularly appeared in television dramas.

Drake first gained wide attention for her portrayal of Lieutenant Gay Ellis in the 1970 science fiction television series UFO, in which her costume consisted of a silver suit and a purple wig.[3] In the series, the character of Lt Ellis is the commander of Moonbase, which is Earth’s first line of defence against invading flying saucers. Drake appeared in roughly half the 26 episodes produced, leaving the series during a break in the production to pursue other acting opportunities.

In 1971 Drake appeared in a short film entitled Crash!, based on a chapter in J. G. Ballard‘s book The Atrocity Exhibition. The film, directed by Harley Cokeliss, featured Ballard talking about the ideas in his book. Drake appeared as a passenger and car-crash victim. Ballard later developed the idea into his 1973 novel Crash.[4] In his draft of the novel he mentioned Drake by name, but references to her were removed from the published version.[4] In 2009, Ballard appeared on the BBC documentary series Synth Britannia and played Gary Numan‘s song Cars. He interspersed clips of Drake from Crash! with Numan’s 1979 video. A reviewer in The Scotsman commented that the presence of Drake “brought serious glamour to urban alienation”.

In the early 1970s Drake was associated with the boom in British sexploitation movies, repeatedly appearing nude or topless. She played a nude artist’s model in the 1970 filmConnecting Rooms, and was one of Peter Sellers‘ conquests in the film There’s a Girl in My Soup. She also played one of the lead roles in the sex comedy Au Pair Girls (1972) and appeared in two Derek Ford films, Suburban Wives (1972) and its sequel Commuter Husbands (1973), in which she played the narrator who links the disparate episodes together.

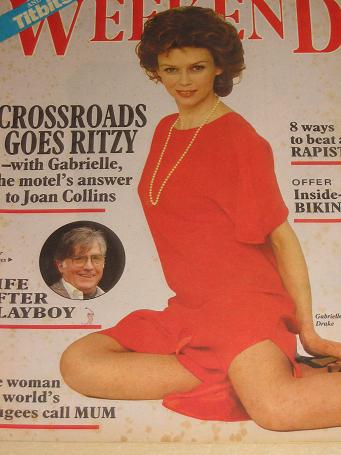

Her early television appearances include The Avengers (1967), Coronation Street (as Inga Olsen in 1967) and The Saint (1968). In 1970, she auditioned for the part of Jo Grantin Doctor Who, reaching the final shortlist of three, but did not get the part. She had roles in The Brothers (1972–74, in a regular leading role), She also appeared in an episode of Brian Clemens’ ’70s series Thriller, in The Kelly Monteith Show (as Monteith’s wife 1979–80), a television version of The Importance of Being Earnest (1985, for LWT/PBS),Crossroads (1985–87, as motel boss Nicola Freeman) and returned to Coronation Street in 2009 as Vanessa. In The Inspector Lynley Mysteries (2003–05) she played the protagonist’s mother.

Drake made her stage debut in 1964, during the inaugural season of the Everyman Theatre, Liverpool, playing Cecily in The Importance of Being Earnest. In 1966, she joined the Birmingham Repertory Company and played Queen Isabella in Marlowe’s Edward II. She also had roles in Private Lives (with Renee Asherson), The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles (with Linda Marlowe and Patrick Mower), Twelfth Night and Inadmissible Evidence.[ The following year, she was Roxanne in Cyrano de Bergerac at the Open Air Theatre, Regent’s Park.] In the 1974-5 season at the Bristol Old Vic, she played in Cowardy Custard, a devised entertainment featuring the words and music of Noël Coward In 1975, she appeared as Madeline Bassett in the original London cast of the Andrew Lloyd Webber and Alan Ayckbourn musical Jeeves. She also appeared in French Without Tears at the Little Theatre, Bristol.[9] In 1978, she played Lavinia, opposite Simon Callow in the title role, in Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, directed by Adrian Noble, at the New Vic, Bristol. She also appeared at the Bristol Old Vic in that year, in Vanbrugh‘s The Provok’d Wife.

She was directed by Mike Ockrent in Look, No Hans!, alongside David Jason, during the 83-84 season at the Theatre Royal, Bath. She made a second appearance in The Importance of Being Earnest at the Royalty Theatre, London, in a production directed by Donald Sinden, which also starred Wendy Hiller, Clive Francis, Phyllida Law and Denis Lawson (87-88).[10] In 1988, she played Fiona Foster in a revival of Ayckbourn’s How the Other Half Loves, first at the Greenwich Theatre, then at the Duke of York’s Theatre.[11]During the 1990-91 season at the Theatre Royal, Bath, she played in Risky Kisses with Ian Lavender.[12] She was in the Mobil Touring Theatre’s official centenary production ofCharley’s Aunt in 1991, with Frank Windsor, Patrick Cargill and Mark Curry.[13] In 1993, she was Monica in Coward’s Present Laughter at the Globe Theatre, London, in a revival directed by and starring Tom Conti.[14] She co-starred with Jeremy Clyde in the 1995 King’s Head Theatre tour of Cavalcade, directed by Dan Crawford.[15] In 1999, she was Vittoria in Paul Kerryson’s production of The White Devil at the Haymarket Theatre, Leicester.[16] She also toured with the Oxford Stage Company in that year, as Hester Bellboys in John Whiting‘s A Penny for a Song, alongside Julian Glover, Jeremy Clyde, and Charles Kay.[17] She played Mrs Malaprop in the 2002 touring production of The Rivals with the British Actors’ Theatre Company, whose artistic director, Kate O’Mara, was Drake’s co-star in the TV series The Brothers.[18]

She has made regular appearances at the Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester, since her debut there in a non-pantomime version of Cinderella, written by Trevor Peacock, in 1979.[ That same year, she co-starred with Sorcha Cusack and Susan Penhaligon in Caspar Wrede’s production of The Cherry Orchard. In 1986, she was Madame Gobette in the British premiere of Maurice Hennequin‘s Court in the Act, which subsequently played at the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre, Guildford, and the Theatre Royal, Bath, before transferring to the Phoenix Theatre in London (1987). Other roles at the Royal Exchange include Mrs Erlynne in Lady Windermere’s Fan (1996);[ Anna in The Ghost Train Tattoo (2000);[ Fay in Loot (2001);[25] Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest (2004);[26] and The Comtesse de la Briere in What Every Woman Knows (2006). At the same theatre in 2001, Drake replaced Patricia Routledge as Mrs Conway during the rehearsal period for J. B. Priestley‘s Time and the Conways, when Routledge was forced to withdraw from the production due to illness.

Elsewhere, she has appeared in her one-woman show, Dear Scheherazade, as the 19th century writer Elizabeth Gaskell (2005, 2007, 2010). At the Chipping Campden Literature Festival in 2011, she and Martin Jarvis read extracts from the letters and diaries of Robert and Clara Schumann in the recital, Beloved Clara. She had appeared in the same piece the previous year, again with Jarvis and the pianist Lucy Parham, at the Wigmore Hall in London.

Drake has helped to ensure the public renown of her brother Nick Drake and her mother Molly Drake. She can be heard accompanying her brother Nick on a number of songs that he recorded privately, and which have since been released on the album Family Tree. After the release of songs written and performed by her mother, she said “Her creativity was a personal thing, and she was lucky to be able to develop it in an environment where that side of her was totally accepted. Indeed, my father encouraged it. He was so proud of her. On one occasion, he even made the 20 mile drive to Birmingham to get four songs pressed onto a disc.”[ In 2004 she published Nick Drake: Remembered for a While, a memoir of her brother.[2]

She lives in Wenlock Abbey in Much Wenlock, Shropshire with her husband of over 40 years the South African-born artist Louis de Wet. The couple bought the house in 1983. She and her husband have renovated their home over several years as an artistic project. In 2004 he described it as “the most beautiful building site in the world”. Drake was the producer of In the Gaze of the Medusa, a 2013 film by Gavin Bush about the renovation project and her husband’s designs for the house.

“There are many different ways of being frightening.” Gabrielle Drake says this in a low, menacing purr, leaning slightly forward and then slightly to one side, like a spinning-top about to keel over. “The obvious way, she says, is the gorgon, the battleaxe, the ugly old boot. “We’ve all seen that.” Her Lady Bracknell will be different: the gorgon with charm. “A woman can be more frightening if she is superbly turned out, superb looking and immaculately polite. You know what her values are and it is very unlikely that you are going to come up to scratch.”

Even as herself, Drake sounds very grand and cut-glass, as if she is about to tick one off for not having the right gloves. Very few actresses talk like this any more and the ones who do would never admit, as she does, that they hate the way they speak. “I think my accent is particularly horrible,” she says, with a shudder. Her voice is actually quite seductive – breathy, conspiratorial and deep. It’s not surprising that she was once invited to read the Kama Sutra on an audiotape of erotic literature. But she has a quaint repertoire of archaic phrases like “thereby reduced” and “raised the ire” – expressions that make her sound like her heroine, Mrs Gaskell, rather than a luvvie having a chat over a cup of tea at the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester.

Still, with her mane of chestnut hair and sparky form, Drake is a cheerful advertisement for the alluring possibilities of middle age. Braham Murray, director of The Importance of Being Earnest at the Exchange, says he chose her to play Lady B because he wanted a spirited, attractive woman and not some “dried up old prune”.

He first met her in 1978 when she was playing Lavinia in Titus Andronicus at Bristol Old Vic and was swept away. “Gaby was stunningly beautiful – still is – but people didn’t take her seriously as an actress. I thought: this is a great, great lady and I used her for some heavy roles such as Time and the Conways.”

Since her debut – as Cecily in The Importance of Being Earnest at Liverpool’s new Everyman Theatre in the Sixties – Gabrielle Drake has deployed her fine vowels in a huge range of modern classic comedies, period drama and minor films (including Suburban Wives and Steal). Her television credits are a catalogue of old faithfuls – The Brothers, Coronation Street, Crossroads, UFO.

Recently, she played Lady Asherton in The Inspector Lynley Mysteries. Last year, she was Mrs Malaprop in Kate O’Mara’s touring production of The Rivals, and now Lady B, a part she was born for. “It’s good fun to be coming into the great comic roles for older women,” she says gamely, though the competition is stiff.

As well as all this, Drake has a non-theatrical role that is only now becoming apparent. Listed in one of her web biographies under the heading “Trivia”, it is “Sister of the late singer-songwriter Nick Drake”. Her younger brother died from an overdose of anti-depressants at the age of 26 in 1974, and she has been the guardian of his reputation and his estate ever since.

At first, this was not too onerous. Nick had a pitifully brief career. Unappreciated in his lifetime, he recorded only three albums – gently melancholic folk-rock songs with an unusually pure guitar accompaniment. His fan base was tiny, though a persistent trickle of followers would turn up at their family home in Warwickshire on the anniversaries of his birth and death.

“Young people would just show up on the doorstep and we would have to be there with tea and cakes. One or two said that if it had not been for his music, they would have ended up as he did.

“His music was an enormous comfort to them. My mum was receiving people at her house almost up to the day of her death. She used to love that.”

In his depression at what he saw as the world’s rejection of his music, Nick seemed to move beyond the reach of family and friends. His parents felt they had failed him. “Other people have had businesses and hobbies,” said his bereaved father. “We’ve had Nick.”

Then, in 1995, something puzzling happened. Nick Drake’s reputation started to take off and has been rising ever since. Gabrielle is suddenly very busy indeed. Recently, she was in London for two days to promote an album of rare and previously unreleased songs to mark the 30th anniversary of his death.

“Wretched boy!” she says, in mock annoyance. “Here I am, still doing his publicity. One of the most difficult things is trying to work out what he would have wanted.

“If I meet him again, I will probably get into terrible trouble. I will have to say to him: ‘Listen, I did my best.’ My deepest sorrow is that he’s not here to do it himself.”

Contemporary musicians such as Paul Weller, Travis, Beth Orton, David Gray and REM are falling over themselves to acknowledge Nick Drake’s influence.

Last month, his first single, Magic, was released and Brad Pitt narrated an hour-long radio documentary of his life, Lost Boy – In Search of Nick Drake. There has been tremendous excitement over the discovery of possibly his last song, Tow the Line, which was found at the end of a reel.

“I am sad,” says his sister, “that the whole Nick thing started after my mother died. She would so loved to have known about it.”

Gabrielle was born in 1944 in Lahore, where her father, an engineer, was building a sawmill. Nick arrived four years later. The family returned to England when Gabrielle was eight. On board the ship home, she loved taking the stage in children’s concerts.

“I was a dreadful exhibitionist,” she says. “My brother was far shyer.”

Their comfortable upbringing in Tanworth-in-Arden seems to have been without a tremor of angst or disharmony. Gabrielle went to Wycombe Abbey School for Girls; Nick to Marlborough College, where he was head boy and a champion sprinter.

She trained at Rada; he dropped out of Cambridge to pursue a musical career under the producer Joe Boyd. For a while, they shared a flat in Hampstead where he showed her his first album, Five Leaves Left.

She says she admired her brother for never trying to disguise his middle-class origins by sounding American or cockney in his songs. “He was what he was and that stood him in good stead with time.

“He was an unfashionable figure; we were both unfashionable figures. To be at Rada and speak with my sort of accent was almost synonymous with lack of talent. I understood his battle from my side.”

But Nick hated the self-exposure of touring and performing live as much as she thrived on it, and gradually he retreated into himself at the lack of public recognition.

“He was a funny combination of not wanting to compromise his work and go commercial, yet wanting his work to be well known. I can’t help but be pleased that it now is.”

She doesn’t subscribe to the theory that his songs in any way prefigured his early death.

“I don’t think The Fruit Tree was necessarily written about himself. After all, that is what happens to a lot of young poets: they don’t flourish till after their death.”

And she believes that although he may have committed suicide, it was not premeditated.

“He was in a pretty low state and I feel that he just threw a whole lot of pills into his mouth and thought: `Either I die or I come out of this and things will be different.’ I think he was always wanting new starts.”

With more sensitivity than most siblings would show, Gabrielle doesn’t lay claim to a special understanding of her brother or his work.

“I try not to talk too much about his music. It would be presumptuous of me and he can’t stand up and defend what I say. I am led by journalists at times to be more definite than I actually feel.”

In musical and business matters, she is happy to take the advice of Nick’s posthumous “manager”.

Besides, she has a career of her own to promote and, as Mrs de Wet, a medieval priory in Shropshire to keep up. Twenty years ago, she and her husband, the painter Louis de Wet, moved into what he described as “the most beautiful building site in the world”.

They have been labouring on it ever since. “It is a mad project and will probably never be finished. It is my husband’s vision to restore it and take it back to something of its medieval beauty – but it is also representative of the way he sees art and his work: making a new link in an old chain.” He is currently building a medieval library.

His wife, meanwhile, is safeguarding against lean times by compiling her own one-woman show about the novelist Elizabeth Gaskell. She tried it out at the Yvonne Arnaud theatre in Guildford and it went down “rather well”, so she will take it touring after her stint as Lady B.

“There are hardly any parts written for women of my age. Work was patchy, so I decided to construct something for myself,” she says, with Bracknellian determination. “Work breeds work.”

This “Telegraph” interview can also be accessed online here.

by Pete Stampede and David K. Smith

Born 30 March 1944 in Lahore, Pakistan, Gabrielle Drake had the distinction of being tested to play Emma Peel and Tara King. She was best known for The Brothers, a 70s BBC evening soap, and was a purple-wigged regular on Gerry Anderson’s UFO(1970). More recently she was a “consultant” on Medics (1995). Her guest turns on TV include The Saint, “The Best Laid Schemes” (1968), The Champions, “Full Circle” (1969) and The Professionals, “Close Quarters” (1978).

Although she usually had minor film parts, particularly sex dramas such as Derek Ford’s Suburban Wives (1971) and Commuter Husbands (1973), she also frequently and successfully played lead roles in the theatre, including Alan Ayckbourn’s How The Other Half Loves and most recently Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan. Whatever possessed her to make a full-frontal appearance as “Randi from Denmark” in Au Pair Girls (1972, with Norman Chappell, Ferdy Mayne and John Le Mesurier), an atrocious soft-core romp, goodness knows! The last credit on record for her is in the “documentary” A Skin Too Few: The Days of Nick Drake (2000) as herself, being Nick Drake‘s sister