James Booth obituary in “The Guardian” in 2005.

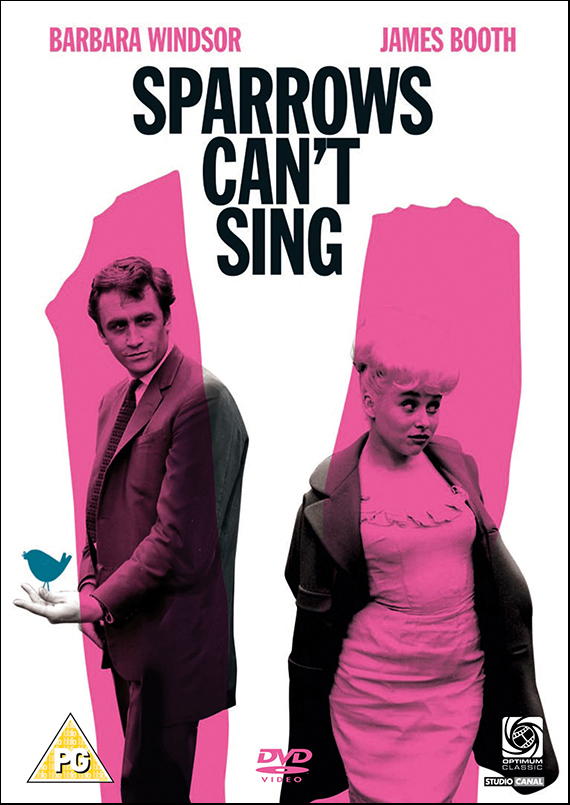

James Booth was born in 1927 in Croydon, Surrey. His movie debut came in 1956 in “The Narrowing Circle”. In 1960 he gained favourable reviews for his role in “The Trials of Oscar Wlde” as Alfred Wood. In 1963 he won the leading role opposite Barbara Windsor in Joan Littlewood’s “Sparrrows Can’t Sing”.

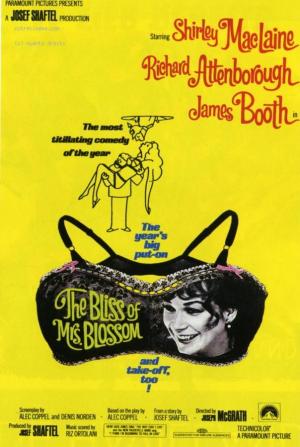

He then had a series of leading roles in such films as “Robbery” with Stanley Baker and “The Bliss of Mrs Blossom” with Shirley MacLaine. He went to Hollywood to continue his career. Towards the end of his life he returned to England. His last film was “Keeping Mum” in 2005, the year he died at the age of 78.

His “Guardian” obituary by Eric Shorter:

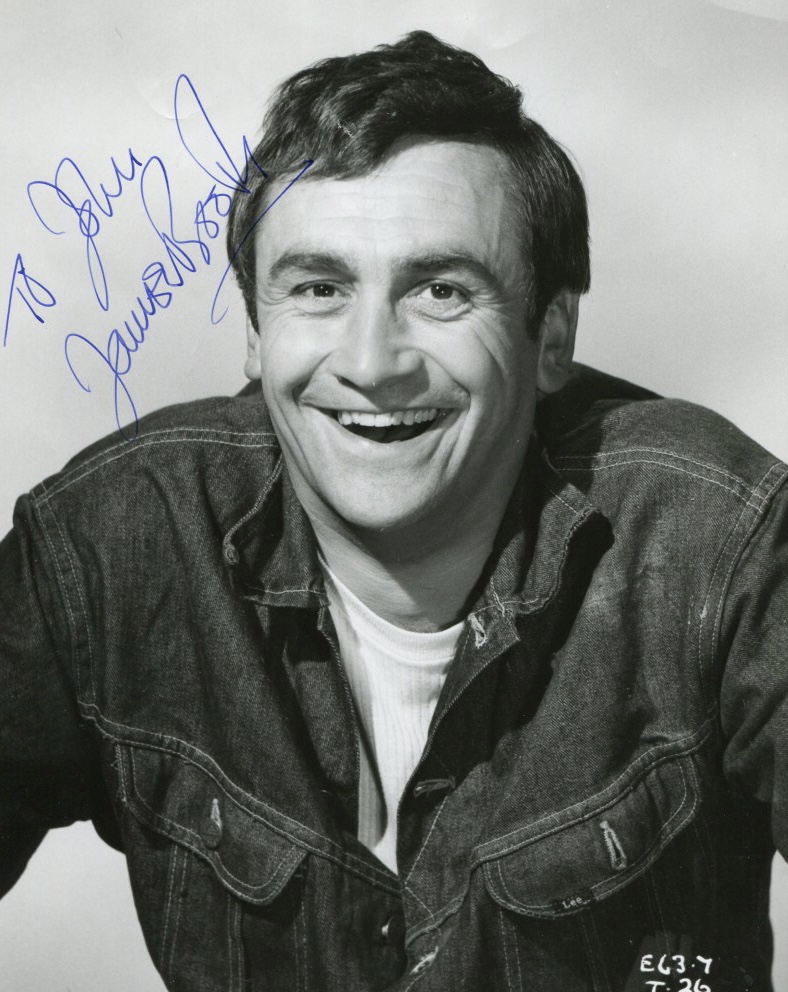

It was amid the social and political upheavals of the postwar British drama – Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop at Stratford East, George Devine at the Royal Court and Peter Hall in London and at Stratford-on-Avon – that James Booth, the character actor who has died at 77, burst on the scene.

Booth seemed to excite the theatre like a fountain of high spirits, with his cockney voice and his mischievous way of expressing himself, sometimes teasing, sometimes truly.

He appeared to conquer whatever he touched, and being at Theatre Workshop the plays could be difficult. Whether old Spanish marital discord in Celestina; Shavian argument (The Man Of Destiny), Irish high farce (Brendan Behan’s The Hostage), low English musical (Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be) or Dickens’ sentiment A Christmas Carol, they were a challenge to a small and largely untrained troupe.

But Booth’s manner with an audience, which he took into his confidence, was so personal. It proved the same in Royal Court revivals of the old British jokes, Box And Cox, or the European ironies of The Fire Raisers, or the call-up humour of Henry Livings’ Nil Carborundum at the Arts. The reason for Booth’s success lay simply with his personality.

His height also helped. He would loom over the footlights with a commandingly wide grin. And his unpretentious manner added to the ease with which these early performances were accepted.

Yet Booth was hardly experienced as an actor. After two years at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art he did eight Shakespeare plays as an Old Vic sword carrier before joining Theatre Workshop at Stratford East. And as Tosher, the lead, in Lionel Bart and Frank Norman’s cockney musical, Fings Ain’t Wot They Used T’Be (a Stratford transfer that had a long West End run), Booth landed one of his richest roles in 1959.

In 1962 he was in two plays at the Royal Shakespeare Company. Critic Kenneth Tynan reckoned that, for him, The Comedy Of Errors, directed by Clifford Williams, gave the company its first sign of “a house style”.

In Peter Brook’s production of King Lear, the arch-villain Edmund was perhaps literally beyond Booth’s technical reach in arguing the difference between Regan and Goneril. At any rate his treatment of Shakespeare’s verse defeated Tynan. His tangled liaisons struck the critic as handling the verse “with the finesse of a gloved pugilist picking up pins.”

Joan Littlewood remarked of Booth at the time: “At all hours you’d find him propping up the bar; a cynical, witty, impossible character, lanky and agile, with his own peculiar life, and acting.” Booth stood for the rebellious spirit of the age, its attitude to middle-class authority, and his nasal speech and clownish instinct usually put him on what he himself would have rated matey terms with his audience – if not the critics. And by failing to regard Shakespeare or Pinter, Behan or Livings, as cherished text, he was being himself.

After another spell with Littlewood as a cheery cockney Robin Hood in her ill-fated staging of a West End musical, Twang!, Booth returned to the classics, though he seemed a far from classical actor. He played Face in Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist at Chichester, Osip in Gogol’s The Government Inspector for the Welsh Drama Company and Archie Rice in John Osborne’s The Entertainer.

In 1974, he played Chief Supt Craddock in Ken Hill’s Gentleman Prefer Anything, the last of his shows at Stratford East. He returned to the RSC the following year, and appeared in Measure For Measure and David Rudkin’s Afore Night Come. He then went to the United States, and was James Joyce in the Broadway production of the RSC’s Travesties by Tom Stoppard. Booth then stayed in the US, writing film and television scripts.

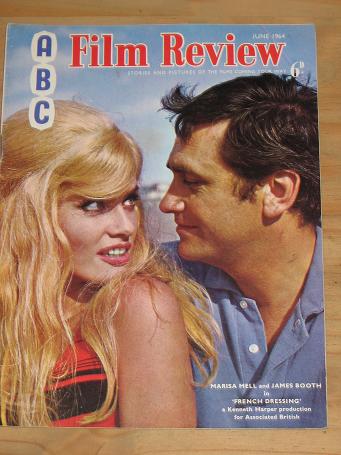

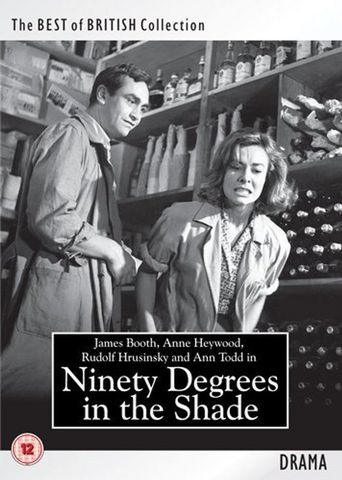

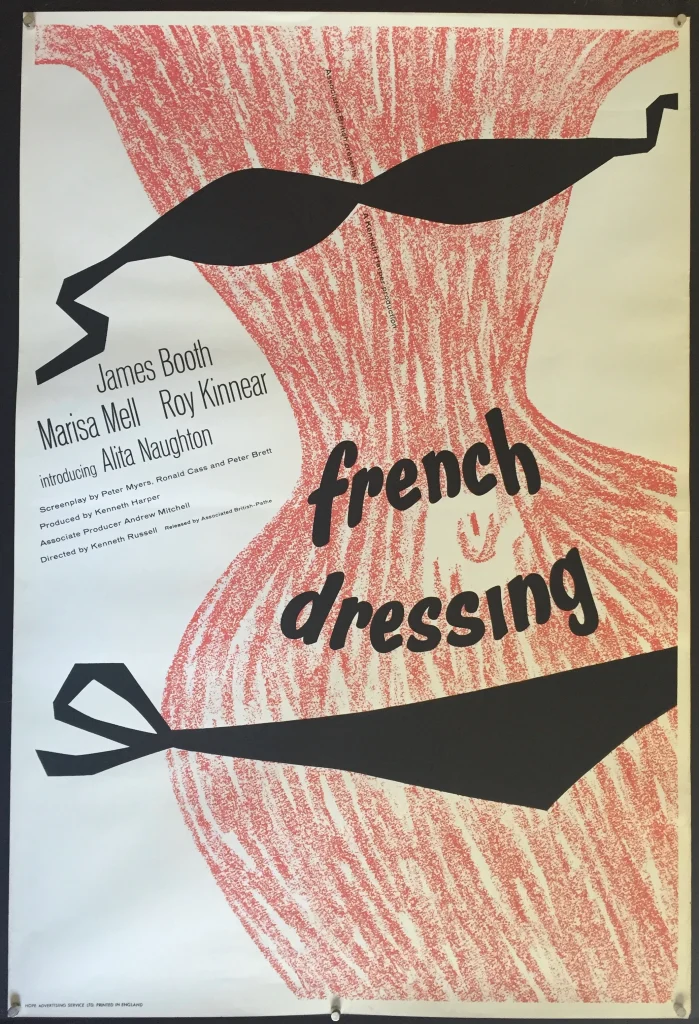

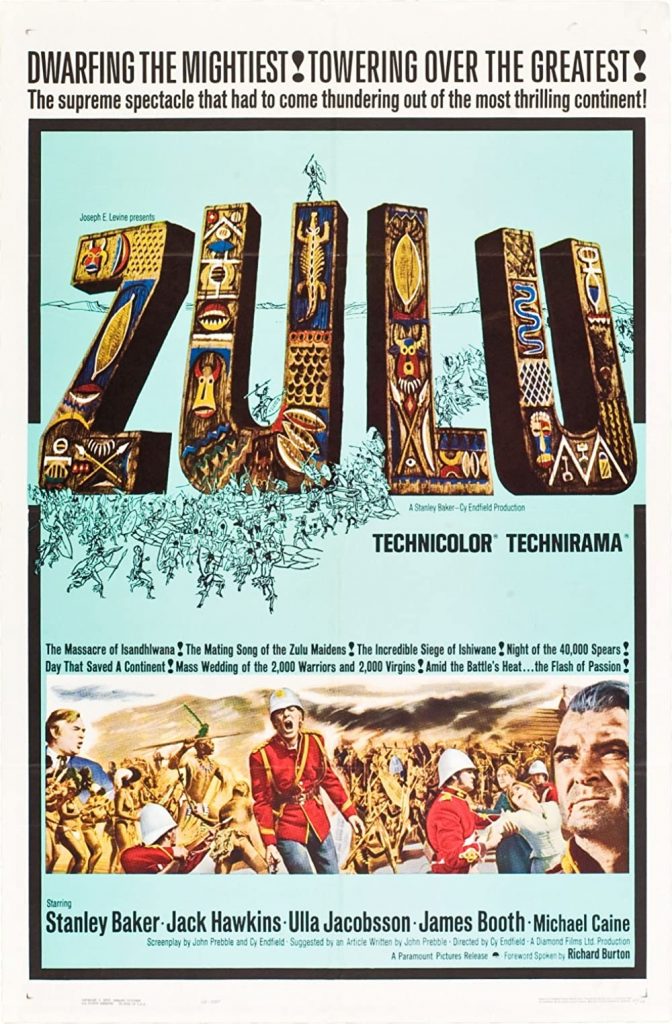

Booth’s films included Littlewood’s screen version of Stephen Lewis’s Sparrers Can’t Sing (1962), opposite Barbara Windsor, Alfred Wood in The Trials Of Oscar Wilde (1960); Ken Russell’s French Dressing and, playing Private Henry Hook, Zulu (both 1964). He was a Scotland Yard inspector in Robbery (1967) and Shirley MacLaine’s secret lover in The Bliss Of Mrs Blossom (1968).

On television he featured in such shows as Minder (1985), Auf Wiedersehen, Pet (1986) and Bergerac (1990), he also played the ex-convict Ernie Niles in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks (1990).

Born David Geeves-Booth at Croydon, Surrey the son of a probation officer, Booth quit Southend Grammar School at 17 and joined the army, and left with the rank of captain. He was interested in amateur dramatics and, while working for a mining company, he won a place at RADA at 24. Albert Finney, Peter O’Toole, Alan Bates and Richard Harris were his fellow students.

· Booth married Paula Delaney in 1960. They had two sons and two daughters. James Booth (David Geeves-Booth), actor, born December 19 1927; died August 11 2005The avove “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.