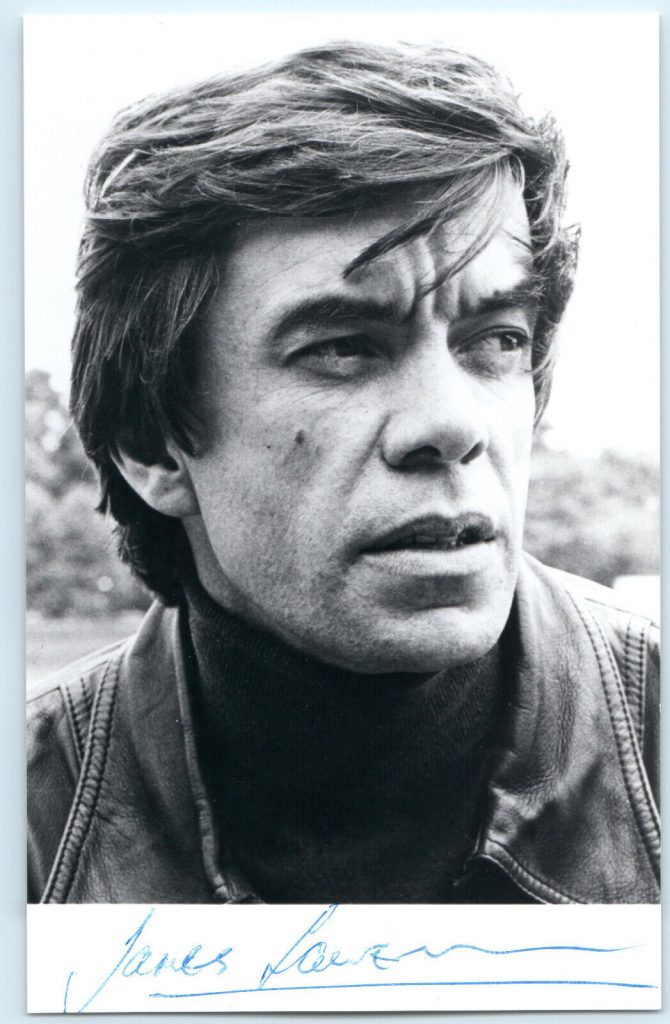

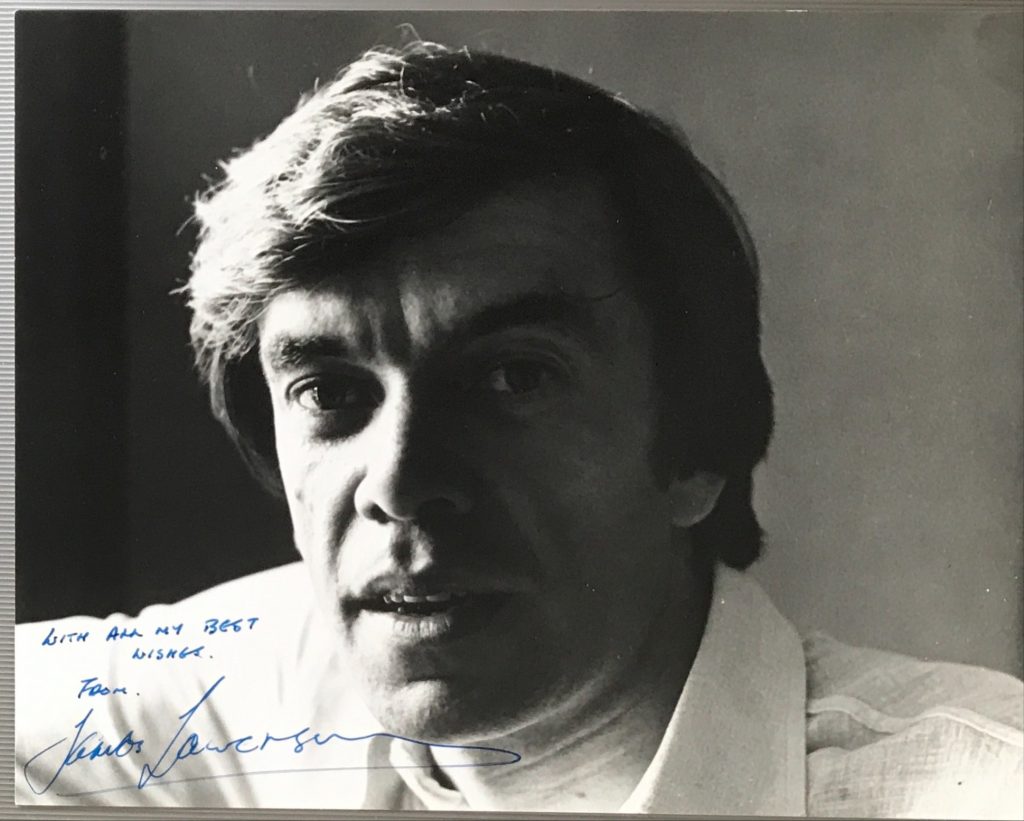

James Laurenson was born in Marton, New Zealand in 1940. He came to Britain in his early twenties. “Women in Love” in 1969 was his first film. Among his other films are “The Magic Christian”, “Assault”, “Pink Floyd: The Wall” .

TCM Overview:

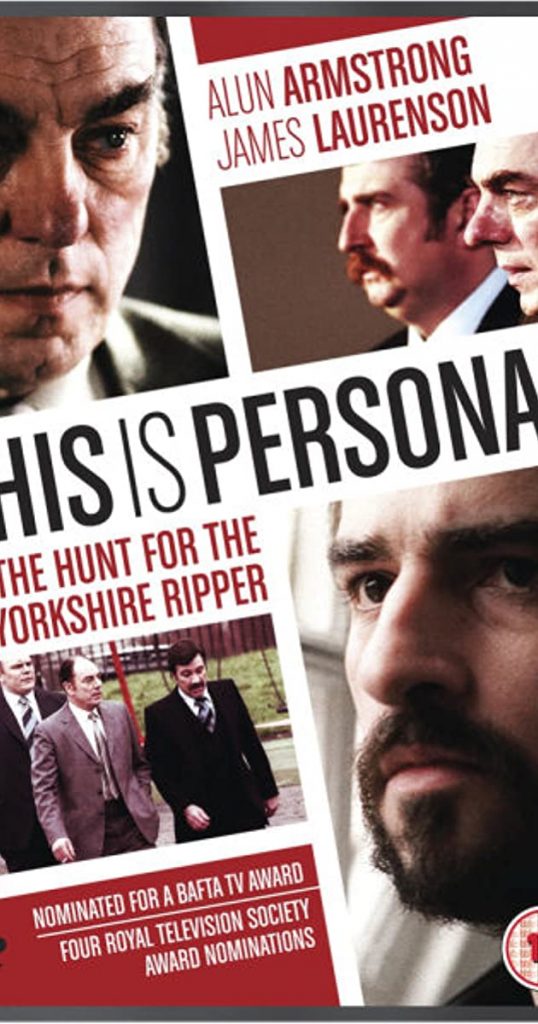

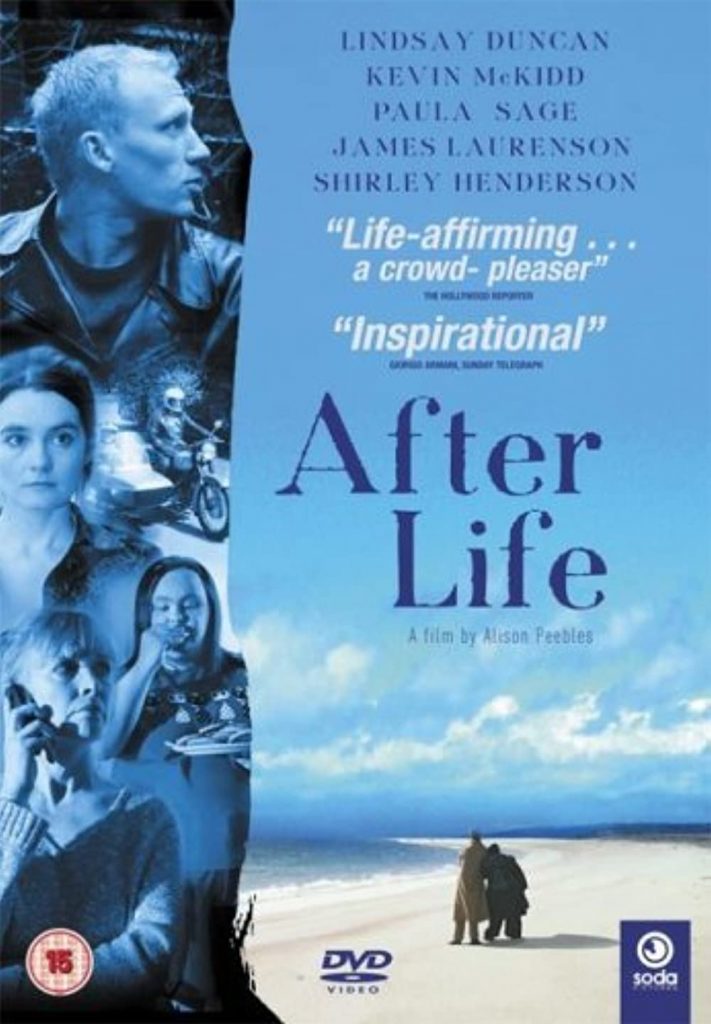

James Laurenson was a prolific actor who created a name for himself largely on the big screen. Laurenson’s acting career began mostly with his roles in various films, such as the Alan Bates dramatic adaptation “Women in Love” (1969), the crime picture “Assault” (1971) with Suzy Kendall and “Pink Floyd The Wall” (1982) with Bob Geldof. He also appeared in “Heartbreakers” (1984). He also was featured in the miniseries “Turn of the Screw” (1973-74). His film career continued throughout the eighties and the nineties in productions like “The Man Inside” (1990) and the thriller “A House in the Hills” (1993) with Michael Madsen. He also landed a role in the miniseries “The Bourne Identity” (1987-88). He also appeared in the TV special “Project: Tin Man” (ABC, 1989-1990). Recently, he tackled roles in the thriller “Three Blind Mice” (2003) with Edward Furlong, the Kevin McKidd drama “AfterLife” (2004) and the Anne Hathaway dramatic adaptation “One Day” (2011). He also appeared in the Sam Claflin drama “The Riot Club” (2015). He also had a part in the TV miniseries “The Hollow Crown” (2012-). Most recently, Laurenson acted on “The Widower” (PBS, 2015-).

The above TCM Overview can also be accessed online here.

Daily telegraph obituary in 2024

James Laurenson, the actor who has died aged 84, arrived in Britain from his native New Zealand in the early 1960s and enjoyed a varied career in theatre, television and film.

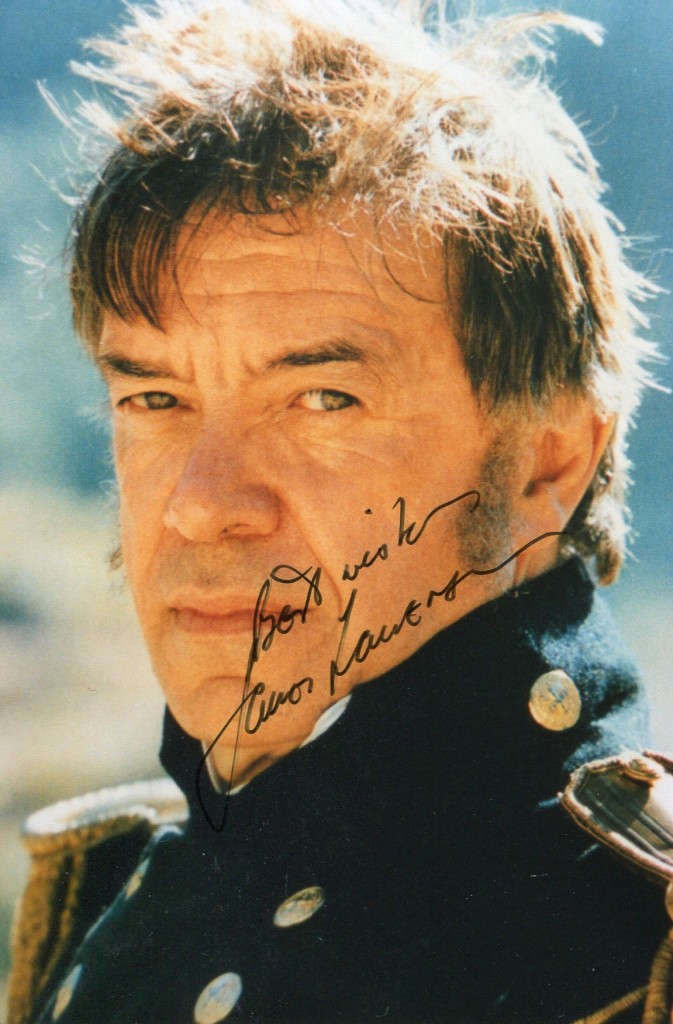

He made his film debut in 1969 with a small part in Ken Russell’s Women in Love and his other screen roles ranged from Major General Ross in the Sharpe television series to Pink’s Father in Alan Parker’s Pink Floyd: The Wall.

On stage he played leading roles for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre and became a regular in productions by the Peter Hall Company after its foundation in 1998. Hall described him as “a great actor, because he had that Everyman quality. All great actors carry with them this quality: when they walk on the stage they do it for us.

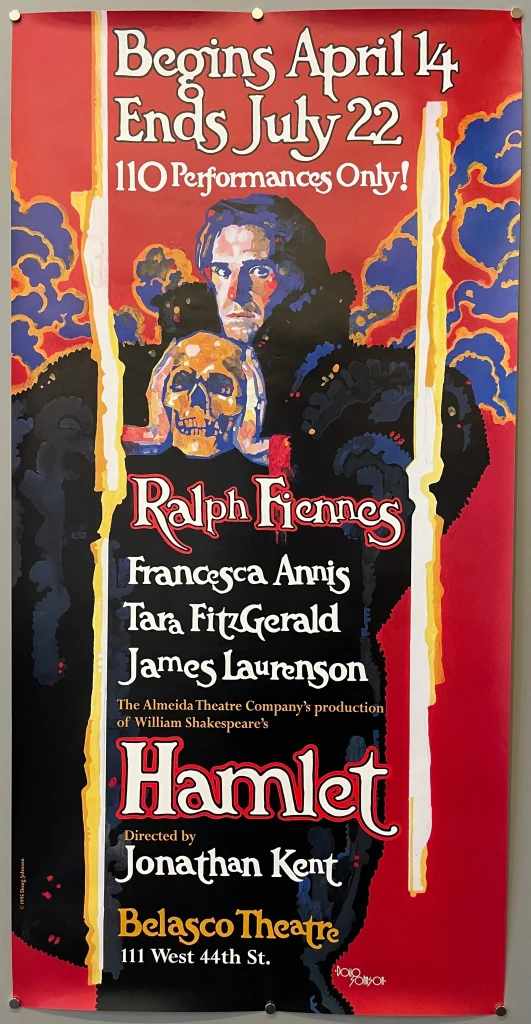

In 2011 he was nominated for an Olivier award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for his portrayal of the Ghost and the Player King in Nicholas Hytner’s acclaimed production of Hamlet, one reviewer noting that as the Player King, normally an ornately speechy role, Laurenson helped to make “the play-within-a-play into a moving tragedy-within-the-tragedy”.

Hytner later forwarded to the cast an ecstatic email he had received from Stephen Sondheim in which he singled out Laurenson’s performance: “When I found myself crying at the Ghost scene, I knew that something special was happening to me (Mr Laurenson gets my gold medal).”

In 1970 Laurenson helped to make television history in a Prospect Theatre Company production of Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II as Piers Gaveston consolidating his relationship with Ian McKellen’s king in television’s first gay kiss. Despite the fact that the BBC Two broadcast came only three years after the decriminalisation of homosexuality, it caused remarkably little commotion

The production had opened at the 1969 Edinburgh Festival before moving to the West End, McKellen recalling that kissing Laurenson (who was not gay) “was a bonus throughout the run”.

Meanwhile, Laurenson became a stalwart of television. In 1968 he took a guest role in Coronation Street as the Reverend Peter Hope of St Mary’s Church. Later on, he had significant roles in both State of Play and Spooks, and his numerous British credits included the usual suspects, among them the first Inspector Morse drama, “The Dead of Jericho” (1987) as well as Bergerac, Lovejoy, Taggart, Prime Suspect and Midsomer Murders. In the US he was seen in Cagney and Lacey and Remington Steele.

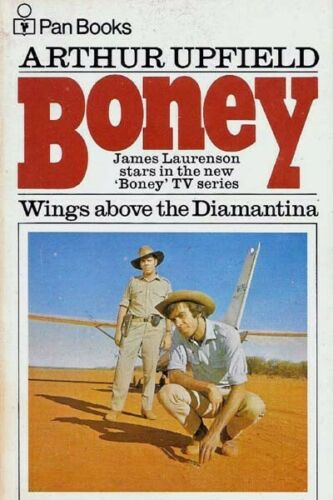

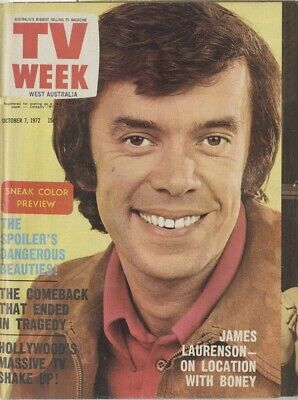

His most significant small-screen appearance, however, was the title role in Boney (1971-2), an Australian detective series centred on the half-Aboriginal Detective Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte, created by the novelist Arthur Upfield.

The casting caused anger, not just because Laurenson, who wore dark make-up for the role, was white, but because he was a Kiwi to boot. However, his performance won admiring reviews, a critic in Australia’s The Age opining that his “tall frame and dark, rugged good looks … should make him Australia’s newest TV sex symbol”, while the Sydney Morning Herald predicted that he would have “half the women of Australia drooling over their sets”.

The series was well received in Britain, where it aired late at night on ITV, though it was not screened in the US, as the distributors said the public would not believe in a lawman who did not carry a gun

James Laurenson was born at Marton on New Zealand’s North Island on February 17 1940. His earliest memory was “seeing a Lockheed Hudson flying over our house and being told that my father was in it”.

His father was also a keen amateur actor and at Canterbury University College, Christchurch, James was directed by the bestselling crime writer Ngaio (later Dame Ngaio) Marsh in several student productions, including the title role in Macbeth. She would dedicate her final novel, Light Thickens, centred on a stage production of Macbeth, to Laurenson.

When he arrived in London in the early 1960s Laurenson recalled that “the first thing I learnt is that it is really hard to find work and be offered scripts. You have to have a passion for acting – Hollywood might come knocking but on the other hand you may spend vast amounts of the time unemployed.” That this was less of a problem for Laurenson than for others soon became obvious, however.

In 1974, he took the lead role in the TV film The Prison, based on a novel by Georges Simenon. In 1984 he took the lead role of Julian Marsh in the West End production of Gower Champion’s musical 42nd Street at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane.

He was Vladimir in Peter Hall’s production of Waiting For Godot and appeared in numerous Shakespeare productions on stage and television, including as the Earl of Westmoreland in adaptations of Henry IV Parts 1 and 2 in The Hollow Crown series on BBC Two (2012)

In the late 1990s Laurenson moved from London to Frome in Somerset and enjoyed some of his busiest years as a regular in the Peter Hall Company summer festival productions at the Theatre Royal, Bath, and on tour.

In 2004 he starred as Roebuck Ramsden and Statue in Man and Superman, Don Luis in Don Juan and Pope Urban in Galileo’s Daughter, and among other roles went on to play Duke Vincentio in Measure for Measure, the blustering prime minister in Shaw’s The Apple Cart, Henry Higgins in Pygmalion, Sir Peter Teazle in Sheridan’s The School for Scandal and Dr Frobisher, the pompously evasive headmaster in Rattigan’s The Browning Version. He also played in company productions of As You Like It in Los Angeles, New York, San Francisco and London

Laurenson did a lot of radio work, including the role of the Squire of Altarnun in Radio 4’s 1991 adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s Jamaica Inn. In 2016, he played the role of the royal physician Sir John Weir in the Netflix series The Crown.

Laurenson relaxed, he told the Western Daily Press in 2012, by “walking our dog, Maisie, down by the River Mells” and was happiest “tucked up with my lady listening to Oscar Peterson and Dizzie Gillespie playing If I Were a Bell”.

His first marriage to the actress Carol Macready ended in 1997. He is survived by his second wife, Cari Haysom, and by his son Jamie from his first marriage.

James Laurenson, born February 17 1940, died April 18 2024