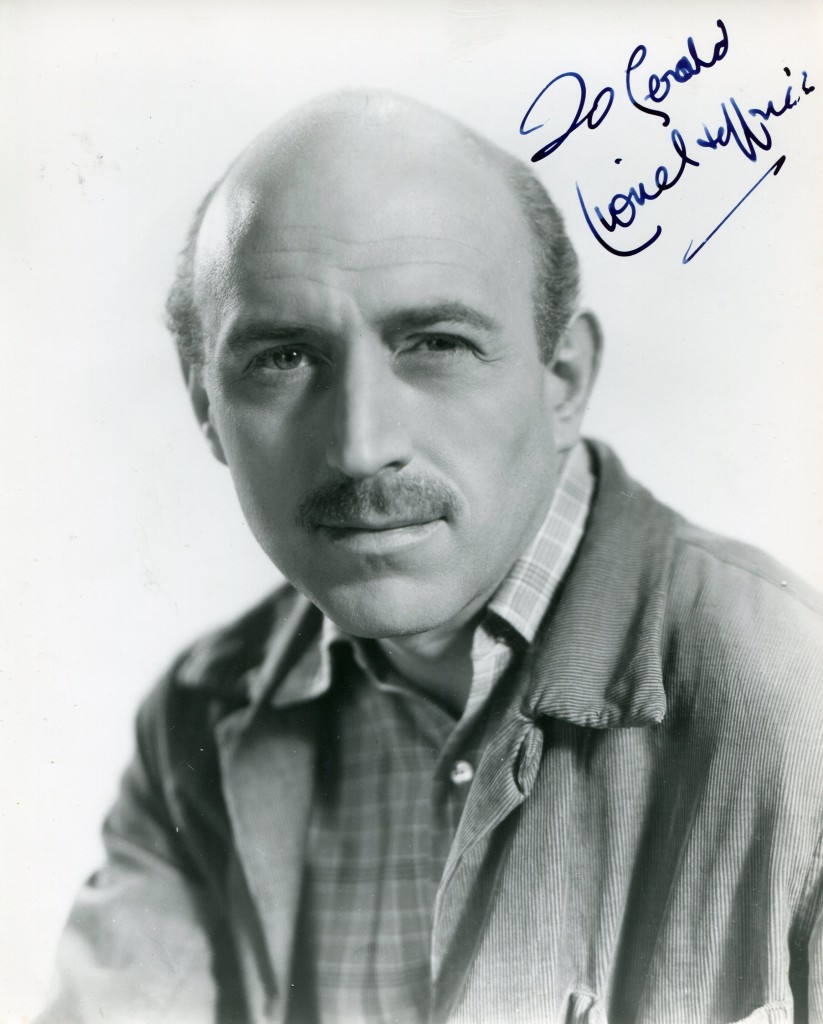

Lionerl Jeffries was born in Poole, Dorset in 1926. He served in the Brtish military during World War Two. He started acting on film around 1950. He can be seen in the Alfred Hitchcock film “Stage Fright” which starred Jane Wyman and Marlene Dietrich. He had a prominent role in “Bhowani Junction” in 1956 and from then onwards was a stalwart of many films during the late 50’s and through much of the sixties. He ventured to Hollywood in 1966 to make “Camelot ” with Richard Harris and Vanessa Redgrave. He played Dick Van Dyke’s father in “Chitty Chitty Bang Banf” even though he was less than two years older than Van Dyke. In 1970 he directed the much loved classic “The Railway Children” with Jenny Agutter as Bobby. He retired from acting in 2001 and died in Dorset in 2010.

His “Guardian” obituary:

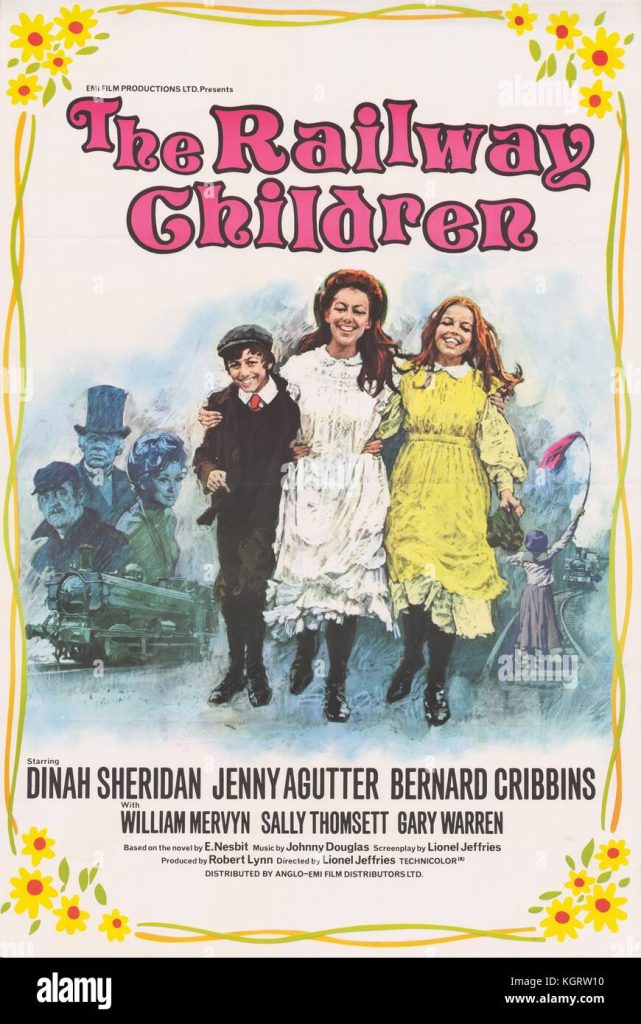

As an actor Lionel Jeffries, who has died aged 83, was a master of comic unease. This was perhaps fuelled by the personal unease he felt in a sex-and-violence era which overtook the gentler sensibilities he sometimes brought to his acting. But he was able to bring these sensibilities fully to bear in his scriptwriting and film directing, particularly in his much-loved adaptation of the classic children’s novel The Railway Children. With the latter, he left an indelible mark on the British film industry and generations of teary-eyed viewers.

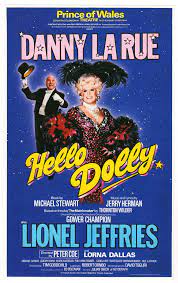

The son of two devoted workers for the Salvation Army, Jeffries disliked personal publicity and was a zealot when preparing a role (he ran two miles every morning before appearing in the musical Hello Dolly! after an absence from the London stage of 26 years). He deplored permissivism, and was not frightened of being quoted to that effect; he was a member of the British Catholic Stage Guild, and served as its vice-president for some time. In a profession sometimes characterised by the loucheness of its morals, he had only one wife, the former actor Eileen Walsh, with whom he had one son and two daughters.

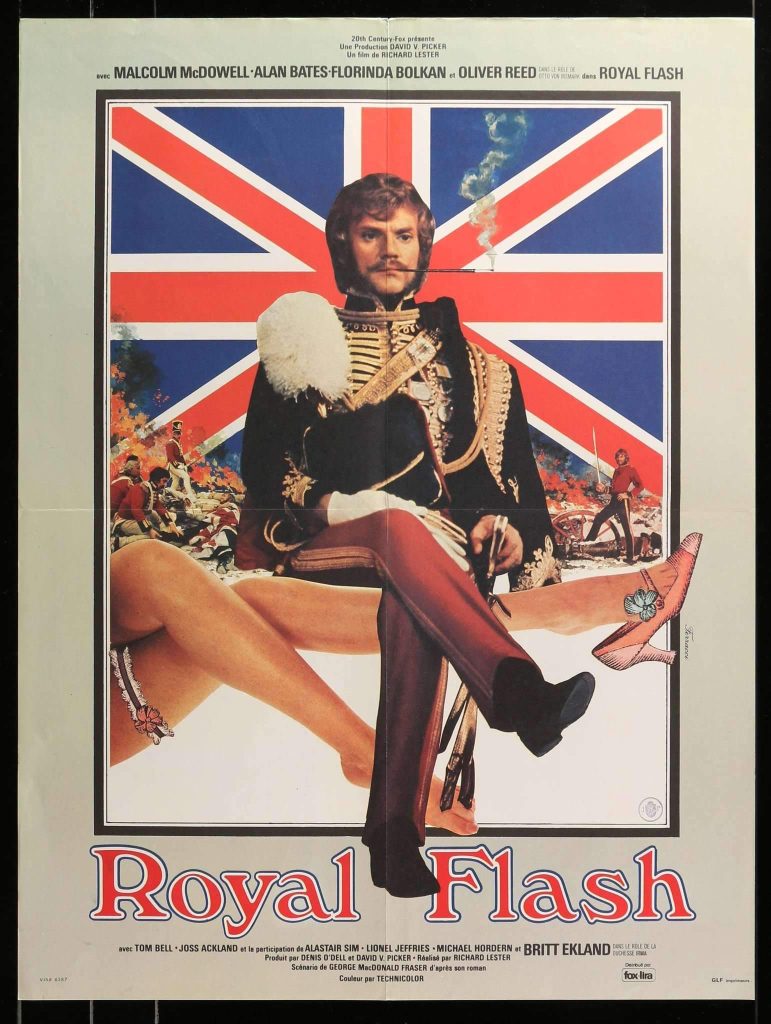

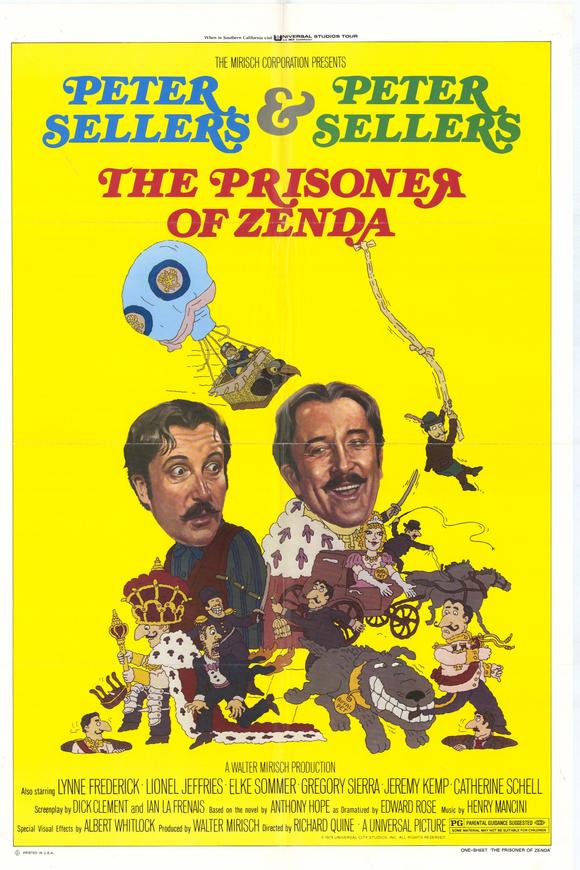

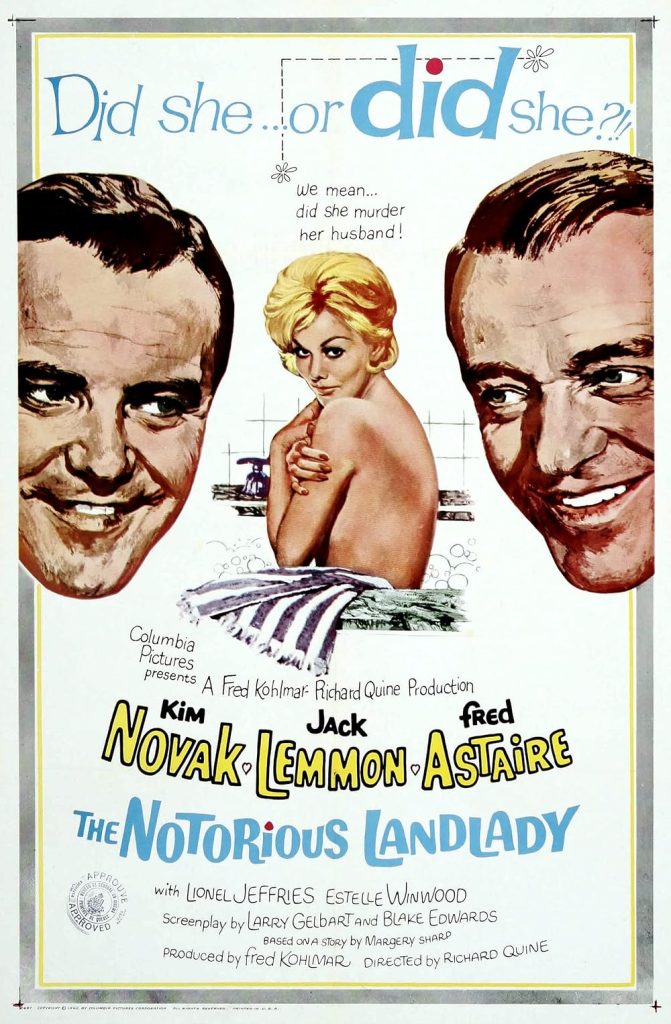

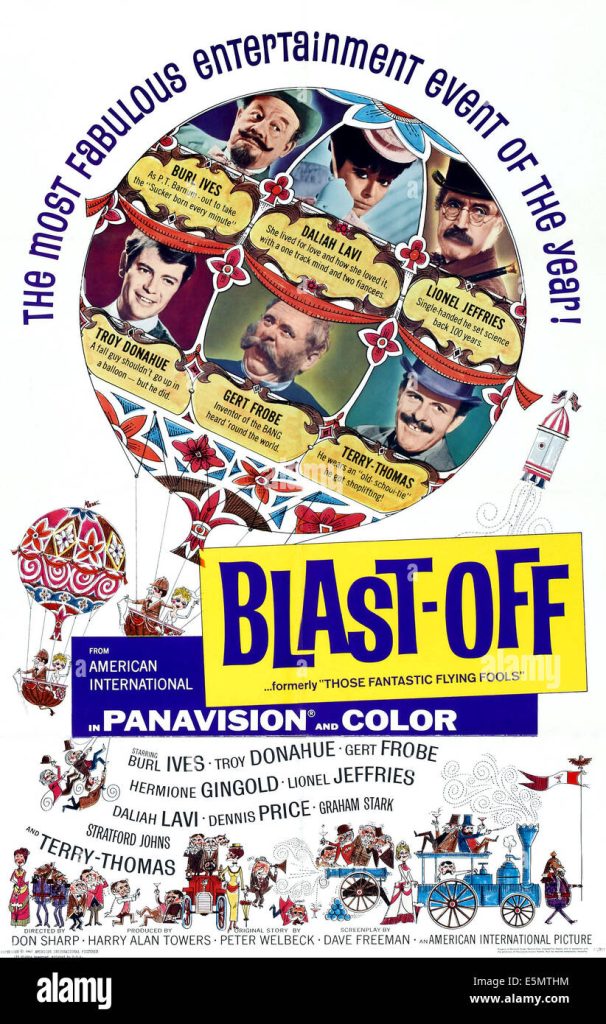

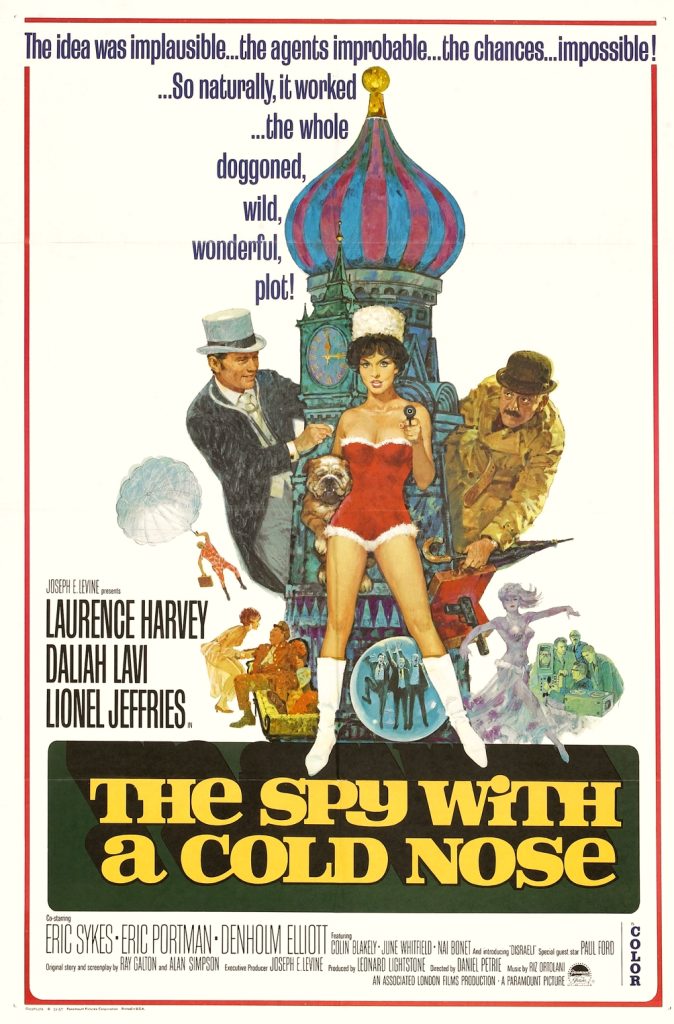

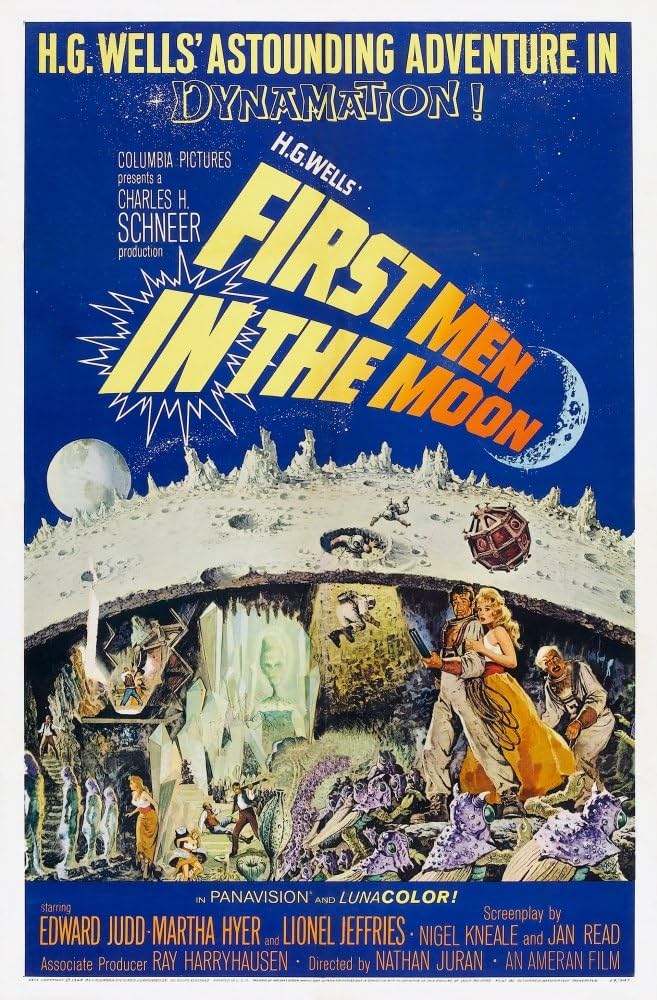

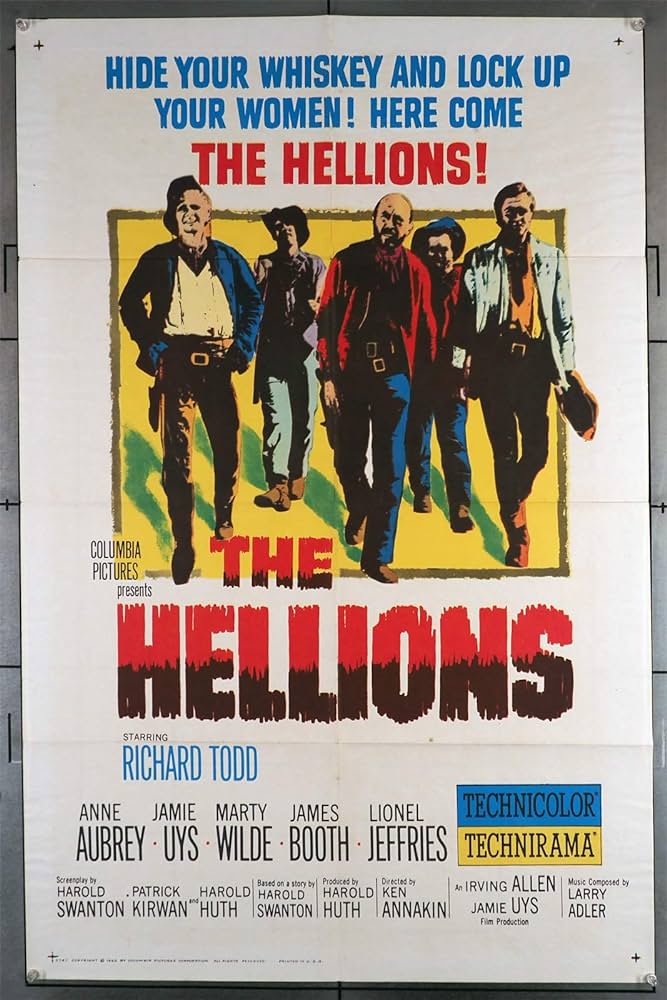

With his hard-boiled egg of a head, barking voice, interrogator’s nose, demented moustache and apprehensive eyes, he was the British film industry’s archetypal officious policeman or half-unhinged bungling crook. For Hollywood, which he called “Shepherd’s Bush wrapped in cellophane”, and the domestic industry he adapted the act in more than 100 films to roles such as the Roundhead colonel in the British civil-war epic The Scarlet Blade (1963), the perfidious Inspector Fred “Nosey” Parker in The Wrong Arm of the Law (1962), and as Stanley Farquhar, the spy who was as inefficient as the dog in The Spy With a Cold Nose (1966).

Such broad comedy roles obscured his more thoughtful and intelligent side. He was a good-natured man who combined a formality of manner sometimes evocative of the constipated behaviour of his comic creations with an instinct for the warm and life-enhancing aspects of writing and direction. When first introduced to the actor and film director Bryan Forbes, on the set of the wartime escape film The Colditz Story (1957), he surprised him by addressing him as “sir”.

The two men and their wives, Eileen and Nanette Newman, became friends. In his polite way, in the 1950s a nd 60s, Jeffries also socialised at The Wick, the handsome Richmond Hill home of the actor Sir John Mills, where he and his wife mixed with the Oliviers, the Nivens, the Attenboroughs, Noël Coward, Deborah Kerr and the playwright Emlyn Williams. His friendship with Forbes was later to launch his own career as a film director.

Born in Forest Hill, south London in 1926, Jeffries attended Queen Elizabeth’s grammar school in Wimborne, Dorset. He grew up just in time to step into wartime service with the Oxford and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and the Royal West African Frontier Force in Burma, and rose to the rank of captain. After the war, he won the Kendal award at Rada — the first of many prizes for his acting and writing — and made his first London stage appearance in Carrington VC at the Westminster Theatre in 1949.

His West End appearances dried up in the early 1950s when his lucrative work for the British film industry took over; it did not resume until 1984, when he played Horace Vandergelder in Hello Dolly! at Birmingham Rep and the Prince of Wales theatre in London.

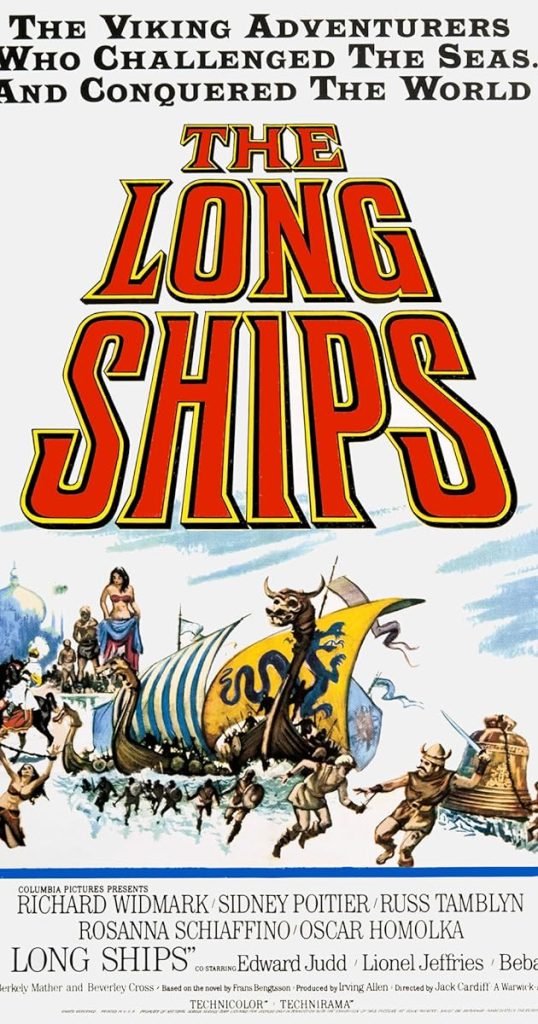

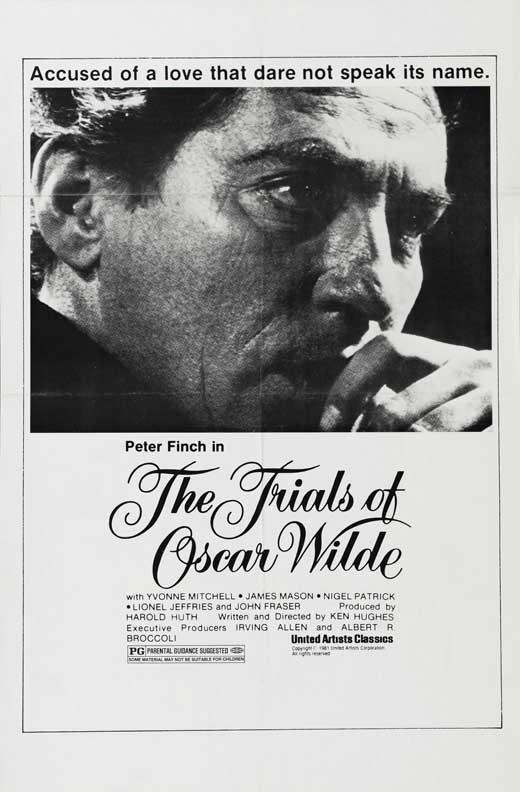

From 1954, he was in a stream of British and Hollywood films. Some roles, such as Lieutenant McDaniel in Bhowani Junction (1956), the Hollywood version of John Masters’s novel about India’s struggle for independence, were serious dramatic parts; others, such as Dr Hatchet in Rank’s Doctor at Large (1957), were slighter and more risible. He enhanced Blue Murder at St Trinian’s (1957), about the madcap girls’ school, and was Grandpa Potts in the successful children’s film Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968), alongside Dick Van Dyke. But he was far from comic as the splenetic Marquis of Queensberry, hounding Oscar Wilde to prison over his son’s liaison with the homosexual playwright, in The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960).

Three of Jeffries’s scripts were made into films. The first was based on E Nesbit’s novel The Railway Children, which Jeffries adapted in pursuit of his belief that there were more wise children than wise adults. When he took his script to Forbes, then head of production at Elstree, Forbes asked him who he visualised as the director. Jeffries replied: “I know it’s a crazy idea and not on, but I’ve always secretly harboured a longing to direct it myself.” The finished film impressed Forbes by its “great style and warmth” and was a financial and cult success, being shown year after year on television, especially at Christmas time.

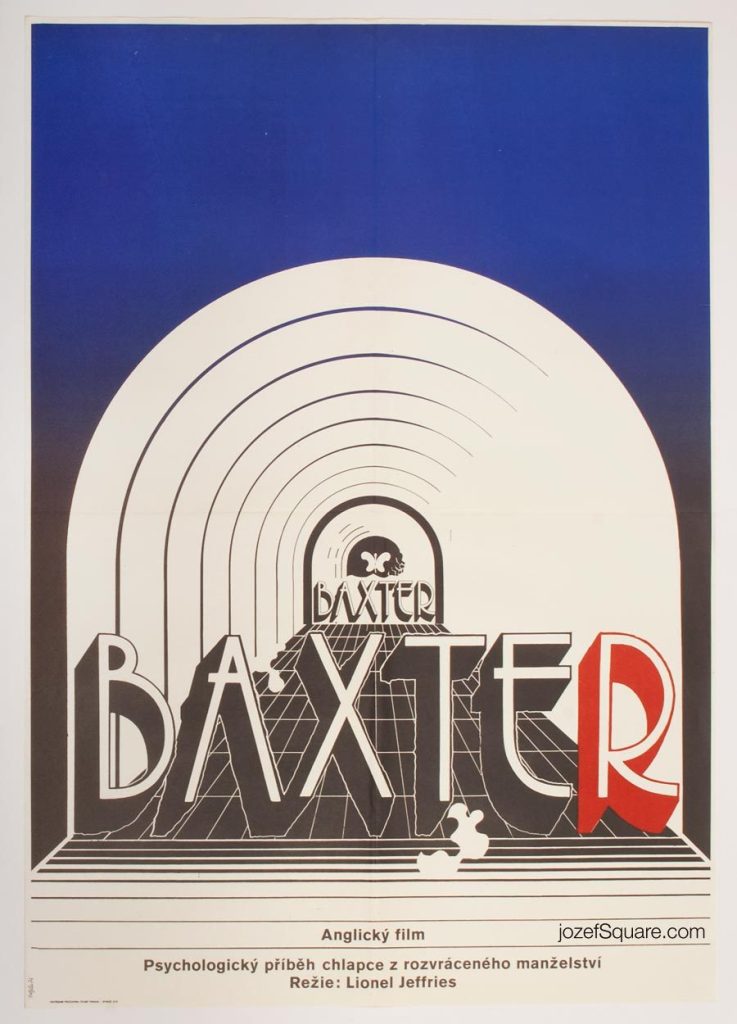

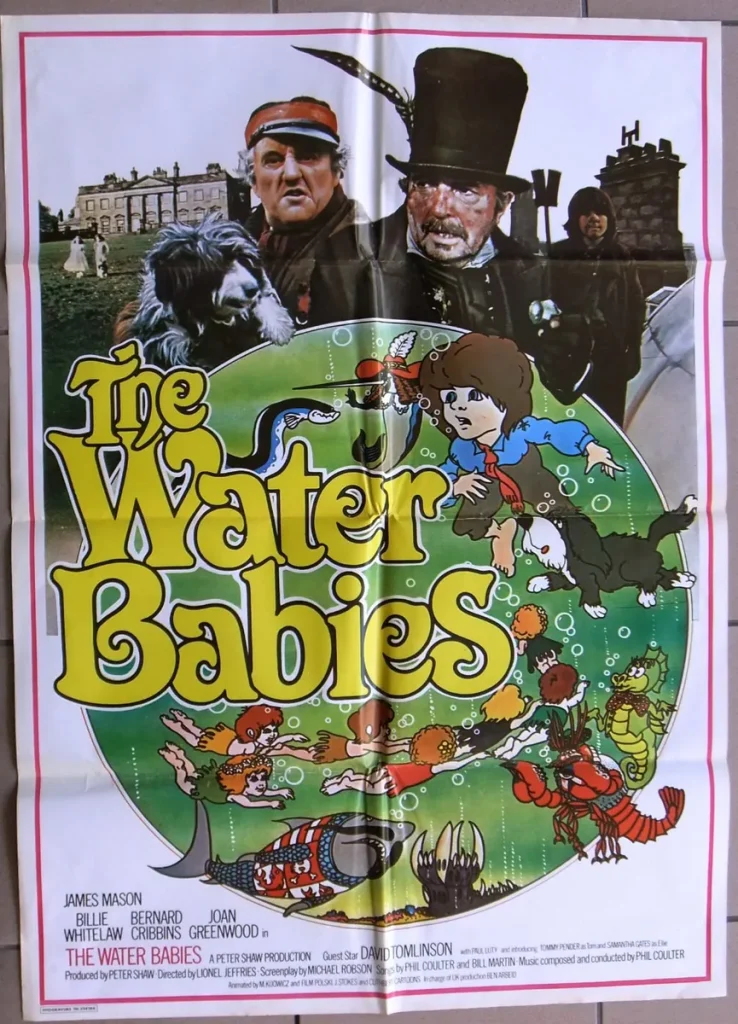

The Amazing Mr Blunden (1972), which he also directed, was a science-fiction film in which Diana Dors played against glamorous type as the repulsive Mrs Wickens. The film won him a gold medal for best screenplay at the International Science Fiction and Fantasy Festival in Paris in 1974. Wombling Free, which Rank made in 1977, was another children’s favourite. He also directed the films Baxter! (1973), and The Water Babies (1979), after Charles Kingsley.

He had many television roles, but his career never really took off in the medium. Although, among jobbing-actor roles in series such as Casualty, Lovejoy and Inspector Morse, he also appeared in the Dennis Potter drama Cream in My Coffee (1980), with Peggy Ashcroft; a TV version of Mr Jekyll and Hyde (1990) and Ending Up (1989), based on the Kingsley Amis novel about old buffers going grumbling to their doom. His constrained but explosive style of acting may not have been quite right for the domesticated small screen, added to which he tended to have bad luck, and twice sued TV companies: first Thames, for negligence, when he was nearly drowned on location; and second Harlech, when a comedy series was abruptly cancelled after the German backers pulled out. His gentlemanly manner did not mean he could not stand up for his rights.

Such an attitude was not the most comfortable one for an actor to have in the tiny world of British TV. But the fact that his directorial flair was so unused on TV, when many lesser talents were allowed to prosper, does not reflect at all well on the openness of that small world.

He is survived by Eileen and his children.

• Lionel Jeffries, actor, screenwriter and director, born 10 June 1926; died 19 February 2010

His “Guardian” obituary can be accessed here.