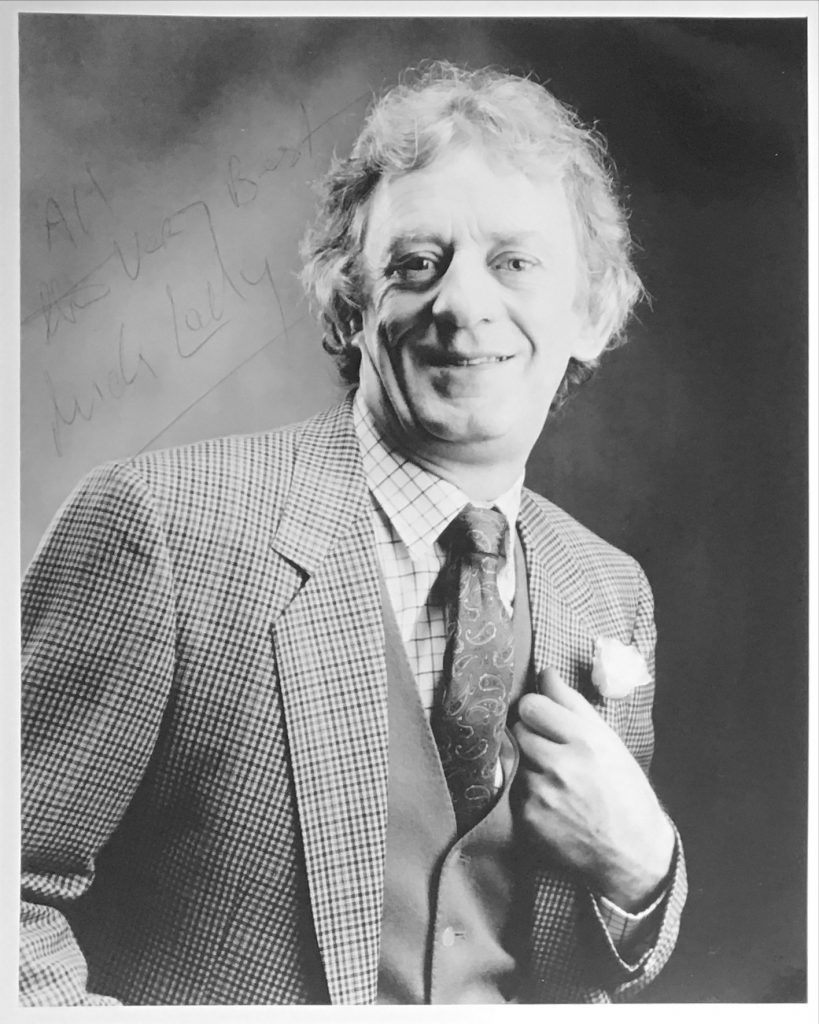

The great Irish actor Mick Lally was born in Tourmakeady, Co. Mayo in 1945. He originally trained to be a teacher and worked in that profession for six years. In 1975 he along with Garry Hynes and Marie Mullen formed the Druid Theatre in Galway. He was a leading actor in many of the Druid Productions. “He gave magnificent performances in The Wood of the Whispering” and “Famine” , He appeared with Gabriel Byrne and Dana Wynter in RTE;s “Bracken” and then went on to play the same character Miley Byrne in the long-running “Glenroe”. His films include “Alexander the Great”, “Circle of Friends” and “A Man of No Importance”. He gave an especially poignent performance in the television adaptation of William Trevor’s “The Ballroom of Romance”. Mick Lally died suddenly in Dublin in 2010. Mick Lally’s “Guardian” obituary by Richard Pine:

The Irish actor Mick Lally, who has died aged 64, succeeded in straddling the worlds of stage, television and film. In particular, he was a vital presence in the renaissance of Irish drama in the 1970s and 80s, while making himself a household name in Radio Telefís Éireann’s soap operas Bracken and Glenroe.

The eldest of seven children on a 30-acre hill farm in Tourmakeady, County Mayo, in the Gaelic-speaking west of Ireland, Lally, through the generosity of a grandfather, attended St Mary’s College in Galway and University College Galway, where he read Irish and history. In extra-curricular time, he acted in the Irish-language college drama society, and won the British and Irish intervarsity boxing championship. He would later comment that acting, even in ensemble, was not unlike being alone in the ring.

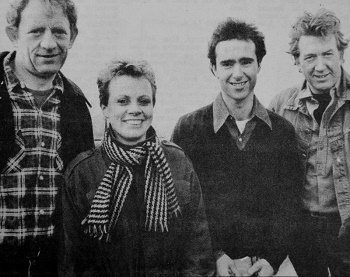

From 1969 Lally taught at a vocational school in Tuam, County Galway, meanwhile acting at Galway’s Irish-language theatre, An Taibhdhearc, until in 1975, with Garry Hynes and Marie Mullen, he founded Druid Theatre Company, which transformed the way in which Irish and international, audiences received both classic and contemporary plays. Their first production was a challenging, chthonic reappraisal of JM Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World, in which he played Christy Mahon, revisiting the play in 1979 as Old Mahon and again in 2005 in the DruidSynge celebration of the playwright’s entire canon on stage and film. Druid went on to lead the way in Irish theatre, and forged an international reputation for presenting new and classic works.

Lally was intimately at home in the western Irish world, its language, its mores, its inevitable decline. His visceral appreciation of rural life allowed him to give memorable performances of Manus O’Donnell in Brian Friel’s Translations (he created the role in the inaugural Field Day production in 1980); of Sanbatch Daly in MJ Molloy’s The Wood of the Whispering (1983); and John Connor in Tom Murphy’s Famine, which he also translated (as Gorta) and directed in 1975.

Parallel with his stage career, Lally was introduced to Irish television audiences in RTÉ’s rural soaps Bracken (1978-83) and its successor Glenroe (1983-2001), playing Miley Byrne, a gauche, innocent, bewildered farmer. Yet beneath the seemingly simple character was a wealth of native knowledge, shrewdness and genetic experience that deepened Lally’s portrayal of a man in a radically changing environment. Lally’s innate strength when impersonating rural characters – and this was his singular genius – came from the sophistication of his personal background. Education had heightened his ability to reach into his personal depths and offer his audiences a unique presence.

Film also claimed Lally’s attention. In 1978 he played opposite Cyril Cusack, Niall Toibin and Donal McCann in Bob Quinn’s Irish-language Poitín; in 1990 with Julie Christie, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio and Iain Glen in Pat O’Connor’s production of William Trevor’s Fools of Fortune; in 1994 with Albert Finney, Michael Gambon and Brenda Fricker in the Wilde-inspired A Man of No Importance; and in 2004 with Colin Farrell in Oliver Stone’s Alexander. These were cameo roles, complemented by similar TV appearances in James Plunkett’s Strumpet City and Thomas Flanagan’s The Year of the French. His TV portrayal of James Duffy, in Joyce’s story A Painful Case (1984), is regarded as a classic interpretation of a classic character.

Lally maintained a strict line between his private and public lives, but inevitably found it difficult to separate himself from, in particular, the persona of Miley Byrne. One wonders, for example, whether it was Lally or Byrne who made a political protest by joining the picket line in 1984, calling for a boycott of Irish shops that imported South African produce.

Lally was diffident about his professional talents, which on occasion could make him appear discourteous when trying to shrug off his many fans. In the rehearsal room and on camera, his stature encouraged younger colleagues to defer to his authority and to his judgment, not merely as a senior figure but as the purveyor of a wisdom, empathy and gravitas seldom encountered.

He is survived by his wife, Peige, their children Saileog, Darach and Maghnus, and by his parents, May and Tommy.

Garry Hynes writes: Mick Lally was a lion of a man. In the early 1970s, he strode through the streets of Galway with his tawny mane, beard, long coat and growing reputation as an actor and significant member of Galway’s arts/music/pubs/whatever you’re having yourself scene. Stories flourished round Mick. One of my favourites concerned a fallen tree which Mick and friends managed to feed through a window in their flat directly on to the fire, where it burned merrily for days.

He left Druid after the first few years, but he never stayed away for long. While his fame grew as Miley in Glenroe, he also created some of his most memorable roles on stage, notably Sanbatch in The Wood of the Whispering. It was an almost forgotten play from the 50s – Mick was not all that enthusiastic when I asked him to read it. But by the end of the first reading, his enthusiasm had shot up and Sanbatch, in this strange fable of a dying community centred round an old man living in the woods, became one of Mick’s greatest performances, with some of his greatest adlibs.

Adlibs were a Lally specialty. While rehearsing a scene where Sanbatch drives the old man, Stephen, dying of cancer, home from the pub in a wheelbarrow, the barrow tipped over, depositing Stephen on the ground. Without losing a beat, Mick said “Ah Jesus, who threw poor Stephen out of the barrow?” The line stayed in.

Mick and Peige made a contented home for themselves and their children in Dublin. Irish was and is the language of the house, and the feasts around their table, starring a revolving cast of family and friends, went on into the early hours with debate, discussion and raucous laughter.

Mick always had a new book, poem, music or something he had read in the paper to share with you. He was a good and cultured man. I’ll miss him to the end of my days.

• Michael Lally, actor, born 10 November 1945; died 31 August 2010

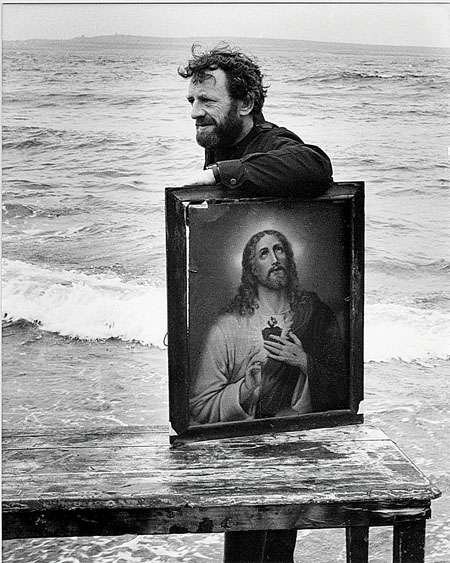

• This article was amended on 14 September 2010. The original named Lally’s character in Tom Murphy’s Famine as John Connell and said that Lally’s education was funded by an uncle. The picture illustrating the obituary was incorrectly captioned as a production of The Well of the Saints.

The “Guardian” website can also be accessed here.

Dictionary of Irish Biography:

Contributed by

Lally, Mick (1945–2010), actor, was born on 10 November 1945 in Tourmakeady, Co. Mayo, the eldest of seven children (two sons and five daughters) of Thomas Lally, a hill farmer with thirty acres, and his wife May (née McGing). The district was bilingual and Lally grew up as a native speaker of Irish. He later recalled the role of radio broadcasts of GAA matches in promoting demand for rural electrification, and traced his interest in the plays of John B. Keane (qv) to a childhood memory of a radio broadcast of Sive.

Educated through Irish at the local national school (walking six miles daily to attend and taking part in school drama productions), Lally then received his secondary education at St Mary’s College, Galway (1960–65). (His fees were paid by his maternal grandfather, who had emigrated to America and strongly believed in education.) Lally had no interest in the prospect of inheriting the family farm – though his parents later offered it to him – and recalled that while boarding school raised his ambitions beyond simple emigration, in many other respects it left him naïve. From 1965 he studied Irish, sociology and history at UCG with the aim of becoming a teacher. He captained the university boxing team, twice winning the British and Irish intervarsity championship, and later remarked that the experience of boxing in a ring was not unlike that of an actor onstage.

Lally’s university years and participation in Galway’s developing bohemian subculture, including the burgeoning folk-music scene, brought general radicalisation. He came to see himself as part of a new generation determined to break with the restrictions of the past, and became a left-wing Labour party supporter, participating in a sit-in at Galway social welfare offices in protest against reduction in small farmers’ benefits. He acted with the UCG drama society, particularly in Irish-language productions. Although Lally’s extensive extracurricular activities led to his being obliged to repeat his final BA exams after failing in 1969, the growing demand for teachers following the implementation of free secondary education enabled him to secure a job even before he graduated BA and H.Dip.Ed. (1970).

He taught in Tuam Vocational School (1969–75), and later recalled that he had tried to make teaching fun, encouraging his students to act out Irish-language stories and appear in feiseanna. At the same time, he acted with the Galway-based Irish-language theatre company An Taibhdhearc, appearing in up to eight productions per year; his height and craggy features made him a well-known figure on the Galway scene. He was also noted throughout his career for vocal flexibility and love of language. He described himself as an instinctive actor who, like most of his theatre contemporaries, received little or no training and learned by experience.

In 1975 Lally was considering emigrating to London for the summer (to combine work on building sites with inquiries about the possibility of entering the city’s theatrical scene) when he accepted the invitation of Garry Hynes and Marie Mullen to join them as a co-founder of the Druid theatre company, based in Galway city. In the company’s production that August of ‘The playboy of the western world’ by J. M. Synge (qv), Lally played Christy Mahon. (In a 1982 Druid touring production he played Christy’s father, Old Mahon, a part he revisited in the filmed DruidSynge version of 2005.) Druid’s most frequent early performing venue was the Fo’csle, a tiny studio auditorium seating little more than forty; Lally later joked that the Fo’csle’s small scale made it ideal training for television acting. Initially without government funding, Druid developed into the only professional theatre company in Ireland outside Dublin, touring widely to provincial theatres and community halls. Lally participated in the company’s tour to Australia in 1987 to participate in celebrations of the bicentenary of European settlement; appearing in the ‘Playboy’, he took the opportunity to join a protest demonstration of Aboriginal Australians.

Moving to Dublin late in 1977 (although he continued to appear in Druid productions throughout the 1980s), Lally began to get parts on the Dublin stage. During his career he appeared in twenty-three Abbey Theatre productions, including a 1991 adaptation by John McGahern (qv) of Tolstoy’s ‘The power of darkness’. Lally’s performance as a blind fiddler in ‘Eejits’ by Ron Hutchinson, a 1978 Project Theatre production, brought him to the attention of the RTÉ head of drama, Louis Lentin (qv), and led to his being cast as a religious maniac in Eugene McCabe’s television play Roma(1979). This role, along with his performance in the series Bracken, won him a Jacob’s television award. Lally later delivered one of four monologues in McCabe’s television drama Tales from the poorhouse (1998), filmed separately in both English and Irish.

By 1979 Lally had secured the role for which he became best known: Miley Byrne in the RTÉ soap operas Bracken (1978–82) and Glenroe (1983–2001). The naïve Miley and his conniving hill-farmer father Dinny (played by Joe Lynch (qv)) were initially introduced as comic relief offsetting the stormy activities of the protagonist of Bracken, Pat Barry (introduced as a character in later seasons of The Riordans, and played by Gabriel Byrne). When Bracken was discontinued, Dinny and Miley were portrayed as selling their land and moving to a new farm in the Wicklow lowlands closer to an urban area, where they became market gardeners (later operating an ‘open farm’ for urban visitors) and were made somewhat more sympathetic figures. Their subsequent activities became the basis of Glenroe.

Lally later admitted that he only expected Glenroe to last for a year or two, and was surprised at the extent of its success. His portrayal of Miley combined an overlay of innocent naïveté (his catchphrase, ‘Well, holy God’, became proverbial) with an underlying body of inarticulate knowledge and fundamental common sense. Lally drew on his own knowledge and youthful experience of farming life, combined with his subsequent training and reflection, to considerable effect; it was often remarked that although Lally differed from Miley in many respects, he consciously refused to condescend to the character or to those who lived such a life or who identified with Miley. The character attracted tremendous popular affection, notably in his courtship of and subsequent marriage to Biddy McDermott (played by Mary McEvoy). Lally was often addressed as ‘Miley’ by people who met him in the street: ‘Even the punks at the top of Grafton Street will stop me and ask how are the carrots and the mushrooms doing’ (Irish Farmers’ Journal, 8 March 1986). In 1990 Lally remarked that many members of the audiences for his theatre productions came expecting to see Miley and left with the impression that they had seen Miley – rather than Lally – playing a part.

To some extent Lally played up this identification with Miley (though they shared certain personal qualities; posthumous tributes from Lally’s co-stars emphasised his gentleness and humility, which were conspicuous sources of Miley’s appeal to audiences). In 1985 Lally participated in an April Fool’s Day joke, announcing on the radio news programme Morning Ireland that he was resigning from Glenroe because RTÉ wished to introduce nude scenes. (Such an objection would have been more in character for the pious Miley than for Lally. Some years before his death Lally publicly revealed that he was a longstanding atheist, believing the suffering and cruelty in the world incompatible with the concept of a benevolent God.) In 1985, when Lally joined a picket line in support of Dunnes Stores workers who had been dismissed for refusing to handle goods imported from apartheid South Africa, it was suggested that it was unclear whether he was appearing as himself or as Miley. (Other activities associated with his left-wing political commitments, such as fund-raising events in support of the beleaguered leftist Sandinista regime in Nicaragua and canvassing for the far-left political activist Joe Higgins in Dáil Éireann elections, were more clearly undertaken in propria persona.) In 1990 Lally as Miley even had an Irish chart hit with ‘The by-road to Glenroe’. Lally filmed the series every season from August to April, and engaged in travelling theatre productions during the summer hiatus.

In tandem with the last season of Glenroe (2000–01), Lally appeared in the sixth and last season of the BBC drama Ballykissangel (also filmed in Wicklow) as Louis Dargan, a solitary, inarticulate and economically marginal hill farmer. After the demise of both serials, Lally mainly engaged in touring theatre productions, although he continued to do television and film work. In 2008–09 he played a businessman in the Irish-language soap opera Ros na Rún, on TG4.

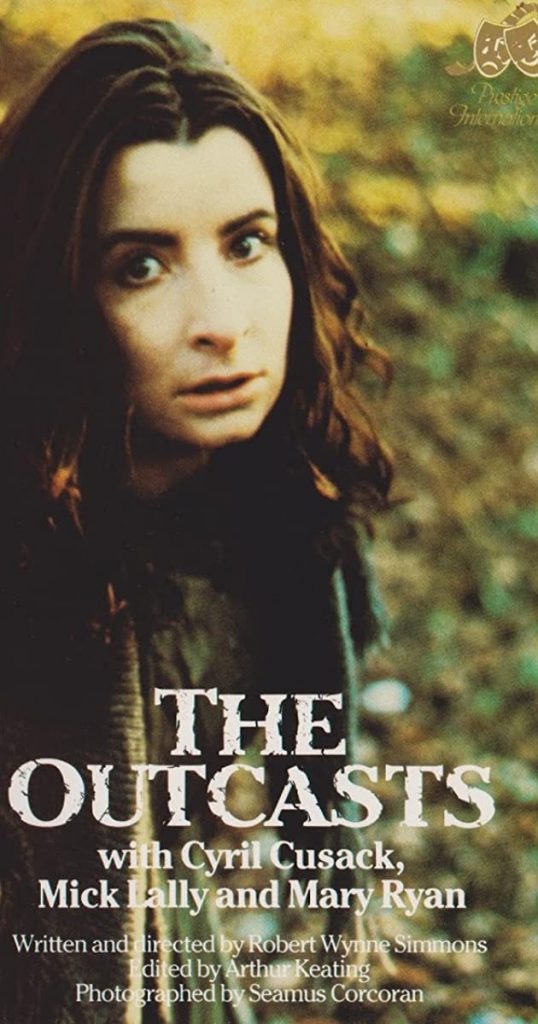

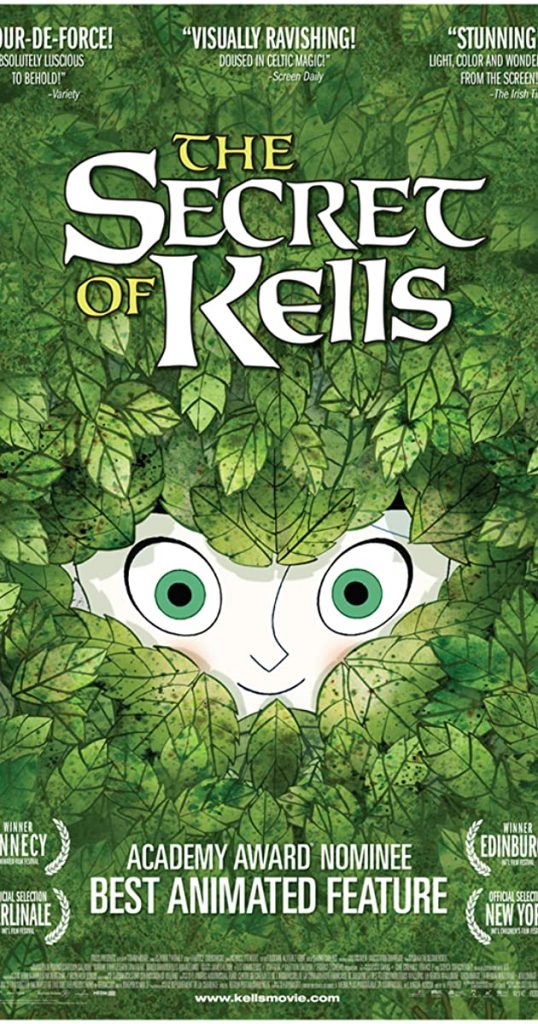

Lally appeared as a garda sergeant in Poitín (1978; dir. Bob Quinn), the first feature film made entirely in Irish, and his performance as the charismatic and sinister wandering shaman-fiddler Scarf Michael in The outcasts (1982; dir. Robert Wynne-Simmons), a horror film set in pre-famine Ireland, was critically praised. Other film appearances (mostly cameos) included The ballroom of romance (1982; dir. Pat O’Connor), Fools of fortune (1990; dir. Pat O’Connor), The secret of Roan Inish (1994; dir. John Sayles), as a horse seller in Alexander (2004; dir. Oliver Stone), and in the animated The secret of Kells (2009; dir. Tomm Moore) as the voice of the illuminator Brother Aidan. Lally declared, however, that he was primarily a theatre actor who saw film and television as stimulating variations on his true vocation.

On stage and in television plays Lally frequently played Irish countrymen and culturally conservative individuals in works by such authors as Keane, McCabe and Tom Murphy, though these were often isolated or deranged figures contrasting sharply with Miley’s benignity and deliberately intended to counter idealised images of the peasant as archetypal Irishman. Such roles included the lonely Sanbatch Daly, trying to hold a declining community together, in the 1983 Druid production of ‘The wood of the whispering’ by M. J. Molloy (qv); John Connor, the morally disintegrating O’Connellite village leader in the 1984 Druid production of Murphy’s ‘Famine’ (which Lally had translated into Irish, and performed, as ‘Gorta’, in 1975); the violent, pseudo-aristocratic fantasist Cornelius Melody in ‘A touch of the poet’ by Eugene O’Neill (1987 Druid production); the embattled conservative teacher Raphael Bell in the 1990 Macnas adaptation of ‘The dead school’ by Patrick McCabe; and the gravedigger suspected of murdering his wife in Martin McDonagh’s ‘A skull in Connemara’ (1997).

In 1980 Lally went to Derry city to create the role of the lame, frustrated schoolteacher Manus O’Donnell in ‘Translations’ by Brian Friel (qv), the first production of the Field Day company, and was depressed by seeing the Northern Ireland troubles at first hand. In the 1990s and 2000s he participated in the generally successful project of the director Ben Barnes to rehabilitate Keane’s image as a serious dramatist by staging innovative productions of major Keane plays involving revised texts developed in collaboration with the playwright. Lally drew particular attention for his portrayal of a lost, isolated and anguished Bull McCabe in ‘The field’ (as distinct from earlier renderings, notably by Ray McAnally (qv), which played up the character’s demonic violence), of the title character in ‘The year of the hiker’ (who returns years after abandoning his family to become a tramp), and of the frustrated bachelor John Bosco Hogan in ‘The chastitute’.

Lally married Peige (1979), a nurse from Inis Meáin; they had a daughter and two sons, and lived on the South Circular Road, Dublin, where Lally became a familiar sight on his bicycle. Irish was the language of the household; in later life Lally expressed dismay that the language-teaching methods his children experienced in school were fundamentally unchanged from what he had experienced in his own teaching career. Despite his atheism, his children received a Roman catholic education as he did not wish them to be isolated from their classmates. Lally died in a Dublin hospital on 31 August 2010 of a heart condition brought on by the emphysema that affected him in the last years of his life, and received a humanist funeral ceremony. In 2014 the Druid theatre’s auditorium in Galway city was renamed the Mick Lally Theatre. This was particularly fitting; for while Lally will be primarily remembered as Miley Byrne, his role in bringing modern literary stage drama to provincial Ireland was more fugitive but quite possibly more important.

Sources

Ir. Farmers’ Journal, 8 Mar. 1986; Ir. Times, 27 June, 21 Nov. 1987; 9 July 1988; 16 July 1990; 16 Mar. 1993; 23 July 1998; 25 Oct. 2008; 1, 3, 4, 8 Sept. 2010; 9 Oct. 2013; Cork Examiner, 26 Aug. 1987; 4, 17 May 1999; 24 Feb., 18 Aug. 2001; Sunday Independent, 12 July 1988; 5 Sept. 2010; Southern Star, 28 July 1990; Connacht Tribune, 17 Sept. 2004; Ir. Independent, 2 Nov. 2006; Ir. Catholic, 2, 16 Sept. 2010; Guardian, 9 Sept. 2010; Independent (London), 11 Sept. 2010; Druid Theatre Company, www.druid.ie (accessed May 2016)