Celia Lipton was born in 1923 in Edinburgh. Her film debut was “Calling Paul Temple” in 1948 and “The Tall Headlines”. By 1954 she was in the U.S. mainly appearing on television. She died in 2011 at the age of 87.

“MailOnline” article on Celia Lipton:

On a summer night in 1955, an attractive young British actress, finding the lift out of order in a Manhattan apartment building, arrived panting at her friend’s front door on the top floor. It was like a scene straight out of the Hollywood classic, How To Marry A Millionaire.

She remembers: ‘I was breathing heavily and almost banged straight into a ladder standing right outside.

‘Looking up, I saw a man with black curly hair and the most expressive, brooding brown eyes that seemed to momentarily flash a sign of recognition, while he stood on top of the ladder.

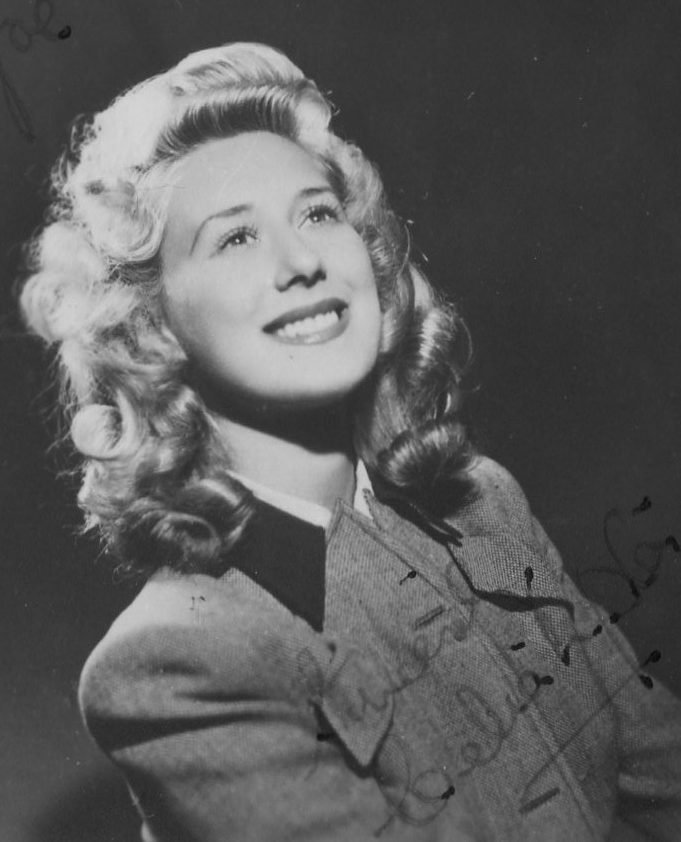

A life less ordinary: Celia Lipton as a young music star

‘He was in the midst of repairing the skylight, and, noting his rolled up shirtsleeves and open shirt, I thought to myself, “What a good-looking plumber”‘.

But to her surprise, the ‘good-looking plumber’ followed her into her friend’s apartment, and was introduced as Victor Farris, a name that meant nothing to Celia Lipton, the 31-year-old West End musical star, singer, actress and daughter of Mayfair’s celebrated Grosvenor House Hotel bandleader, Sydney Lipton.

After hesitantly accepting his offer to drive her home, in ‘the most awful-looking pale blue Cadillac I’d ever seen – it bore the scars, dents and scrapes of endless battles for limited parking space on Manhattan’s streets’ – he took her for coffee.

They sat at a table facing the men’s room. ‘Every time a man came out, Victor pretended he was knocking them off with a machine gun. He had me in convulsions. Our one cup of coffee seemed to last for hours, with much laughter. We both found a new camaraderie.’

By the time Farris, divorced and 12 years her senior, dropped her off at her apartment, she was convinced he was a Mafia Don.

She never dreamed that he owned 17 companies, was a millionaire many times over and the inventor of things the world came to take for granted, including the paper milk carton, the paper clip and Farris safety and relief valves.

Celia Lipton had felt an instantaneous attraction to this ‘macho man whose toughness co-existed with humour and sweetness’.

When she had reeled off her acting credits, he had silenced her, declaring that ‘anyone can act’, a statement that outraged her.

‘All night long,’ she writes, ‘my heart pounded, and I thought, “I’m falling for a gangster! What would my father say?”

‘All these thoughts were running through my mind when the phone rang at 3am. It was Victor “Mafia Don” Farris, solicitously enquiring how I was. He called me “Puppy”. I tried to be nonchalant and said: “I’m fine.”

There was a long pause while I wrestled with my head, which told me to slam the receiver down and never talk to this gangster again. But my heart melted at the very sound of his voice.

‘A chastened-sounding Victor told me softly that he was pulling my leg. He wasn’t a gangster at all. Victor wanted to prove to me that “anybody can act”. He certainly convinced me that he could act!’

Six months later, they were married. Lipton gave up her glittering stage and screen career to become his wife – and the acknowledged Queen of Palm Beach society.

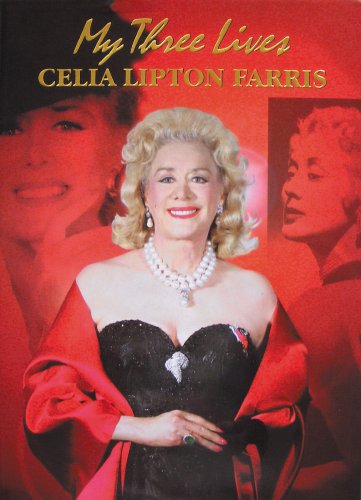

The story of their 29 turbulent, volatile, but deeply happy years together is engagingly told by Celia Lipton Farris, now one of the richest women in the world, in her new autobiography, My Three Lives.

It has to rank as one of the most extraordinary books that has ever come my way.

Lavishly produced in coffee-table format, in almost blinding Technicolor, its 344 pages feature no fewer than 408 photographs, 232 of them of herself.

We have Celia with the Queen, with Prince Philip, with the Prince of Wales, with Princess Diana, with Prince Edward, with Rose Kennedy (the mother of JFK), with Clint Eastwood, with Bob Hope, with a decidedly icy-looking Bette Davis – of whom Farris says: ‘I had the distinct impression that she was wishing I wasn’t with her on stage at all,’ – and of a legion of lesser luminaries who make up the candyfloss world of Palm Beach society.

The New York Post has described the book as ‘an ego trip that counts’. Others might describe it as an ego trip in which you count the pictures.

Yet nowhere in this strange book will you find the date on which its author was born, a matter she declines to countenance, claiming that in America, ‘if you are over 40, you are dead’.

This statement is bound to interest President Barack Obama, who is 47, not to mention Hillary Clinton, 61, and a whole roster of older star ladies such as Lauren Bacall, Dame Elizabeth Taylor, Shirley MacLaine and Debbie Reynolds.

The reality is that on Christmas Day, Celia Lipton Farris was 85, a fact that readers of her book will find impossible to believe after studying the hundreds of photographs in which she appears gleaming, glowing, dressed to the nines, magnificently coiffured and loaded down with jewels that look as if they might have come from the collection of Marie Antoinette.

Celia May Lipton, in fact, was born on December 25, 1923, in Edinburgh, the only child of an English violinist, Sidney John Lipton – as Sydney Lipton he would become one of Britain’s top bandleaders – and of a noted Scottish beauty, May Johnston Parker.

When Celia was eight, her father formed his own band and took it to London’s Grosvenor House Hotel in Park Lane, where he was to remain for 35 years.

Every week, millions of radio listeners tuned in to hear the words: ‘You are listening to Sydney Lipton’s Orchestra broadcasting from the Silver Room at the Grosvenor House Hotel.’

On one occasion in the Fifties, when Lipton and his orchestra played for the Queen at Buckingham Palace, Celia’s mother danced with Group Captain Peter Townsend, the lover of Princess Margaret.

Deeply happy: With Victor Farris on their wedding day in 1956

Both parents attempted to veto Celia’s ambitions to be a performer. But unknown to them, she auditioned for another bandleader, Jack Harris.

When her father heard, he said: ‘I thought, to hell with it. If she’s going to sing with a band, she’ll sing with my band and I can keep an eye on her.’

So, in 1939, at the age of 15, she made her debut at the London Palladium with her father’s orchestra.

At 17, she was back at the Palladium in the revue, Apple Sauce, and four months later, she won her first raves in the West End revue, Get A Load Of This, in which, dressed by the royal couturier Norman Hartnell, she stopped the show every night, singing You’re In My Arms (And A Million Miles Away).

At 20, she played the title role in Peter Pan. The turning-point for Celia came in 1944, when superstar Jessie Matthews walked out of the leading role in the West End revival of The Quaker Girl.

Lipton stepped in at only ten days’ notice, and when the production reached the West End, she took 16 curtain calls and one critic hailed her as ‘the brightest of new stars’.

On the French Riviera, she rubbed shoulders with the young Prince Philip of Greece, before his marriage. ‘He said he’d like to give me a lift to the casino in Cannes,’ she said.

‘I asked him how we were going to get there and he said he’d borrowed a man’s bike and he put me on the back of it. My dress kept catching in the back of the bike – it was really a scream. I got lucky as I danced with him. He was a very good dancer.’

After several more leading roles on the West End stage, and appearances in a number of films, Celia Lipton left Britain in 1952 to try her luck in New York. And there, after two appearances on the Broadway stage, two American TV roles, and some success in cabaret, she met Victor Farris.

They were married at his home in Tenafly, New Jersey. ‘Even though Victor never once suggested that I give up my career, I knew our marriage wouldn’t work if I continued.

‘He wanted a traditional wife, actually the kind my mother was. I wanted to be that for him.’

But their first child, a girl, lived only a day. Their second, a son, was premature and died after a few hours. She suffered, in all, ten miscarriages.

‘My heart was broken,’ she writes. ‘This was a time in my life where I felt useless and inadequate’.

Fortune: Farris left her more than £100million

When, at last, she succeeded in giving birth to two daughters, Marian and Cecile (‘Ce Ce’ for short), Farris was ‘not that enamoured’, and she ‘soon learned that it’s the attention that a child requires that can make a husband irritable. Victor liked to be the centre of attention at all times’.

Although it is clear that their 29-year marriage was not always easy, her account of it, and of Farris’s death in 1985, when she fought desperately to get the paramedics to their Palm Beach mansion, is the one section where her book blazes vividly into authentic literary life.

‘I walked out of the hospital, got into my car, put my head on the steering wheel and sobbed. Finally, after what seemed like hours, I started the car and drove into the bleak, dark night across the Intracoastal Bridge, back to Palm Beach. That five-minute drive home seemed like 500 miles.’

Farris left her a fortune in excess of £100 million. By shrewd investment, she has doubled it, making her one of the wealthiest women on the planet. In widowhood, she started to display her formidable organising abilities.

She became Executive Producer of the American Cinema Awards in Hollywood, sang before the Queen at the 50th anniversary of V.E. Day in Hyde Park, made a brief screen comeback with Burt Reynolds in B.L. Stryker, and released a series of her own, self-financed, nostalgic CDs.

In 2003, she was delighted to learn that her recording of Maybe It’s Because I’m A Londoner was being played to the troops in Iraq. However, the song’s composer, Hubert Gregg, was less delighted.

‘Hers is the worst version of my song I have ever heard,’ he told me, ‘and that includes the Omsk-Siberian Choir – in Russian!’

Her philanthropy has become legendary. She has funded two hospital wings in her husband’s name, has worked devotedly for Aids sufferers, spearheaded a Salvation Army appeal that raised $10 million, and has given huge sums to numerous causes, sometimes with money raised from exhibitions of her own brilliantly coloured impressionist oil paintings.

The American Cancer Society has named a lifetime achievement award after her in honour of her 30 years of charitable work.

Occasionally, her judgment has failed her. Towards the end of her book, she relates that she was ‘honoured to receive a letter informing me that Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth had appointed me a Dame’.

This conveys the impression that she had been created a Dame of the British Empire. Not so. In 2004, she was named a Dame of Grace of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, which entitles her to place the letters, D. St. J, after her name.

Yet she now heads her personal notepaper, Dame Celia Lipton Farris, and is announced by that style on all social occasions. But then, in the neverland kingdom of Florida’s Palm Beach, such distinctions are apt to become blurred.

Is Farris’s book the story of ‘an incredible woman who has led an inspiring life’, as one of its more gushing reviews insists?

Sadly, it could have been, had it not been written with one eye on the calendar, and the other on her socialite neighbours.

Despite that, one feels this is one genuine gutsy dame who doesn’t need a cardboard title from some venerable order of which most people have never even heard.

Nor does she need to fib about her age or assume a status she does not possess merely to impress the rich bitches of Palm Beach.

If her book proves anything at all, it is that Celia Lipton Farris is a real-life heroine who has built her own pedestal.

The above “Mail Online” article can also be accessed here.

The Telegraph obituary in 2011.

Celia Lipton, who died on March 11 aged 87, was a child star, known as the “British Judy Garland”, who went on to become a Forces sweetheart in the Second World War; later she gave up a successful stage career to marry the American inventor and industrialist Victor Farris and became the acknowledged ‘Queen of Palm Beach society’.

22 April 2011 • 6:17pm

Like any society hostess and former actress Celia Lipton was always vague about her age and was furious when a magazine obtained a copy of her birth certificate, showing that Celia May Lipton was born on Christmas Day 1923, at 73 Leamington Terrace, Edinburgh. Her father was an English violinist, Sidney John Lipton — as Sydney Lipton he would become one of Britain’s top bandleaders; her mother was May Johnston Parker, a dancer, singer and noted Scottish beauty.

When Celia was eight, her father formed his own band and took it to the Grosvenor House Hotel in Park Lane, where he was to remain for 35 years. Enthralled by watching the singers and chorus girls at the hotel putting on their make-up and diamonds to go on stage, Celia determined to go into showbusiness. Her chance came when, aged about 10, she spotted an advertisement asking for a Judy Garland sound-alike to play the lead in a BBC radio production of Babes In the Wood. Determined to get the part, she perfected Garland’s lisp and breathy singing style. When her parents refused to let her audition, she set off on her own and secured the part.

She went on to record more radio plays and albums and, aged only 15, appeared at the London Palladium. “My father was leading the orchestra,” she recalled. “He didn’t tell the audience who I was, he just said: ‘There’s a little girl coming out, her name is Celia.’ I sang I’m Just In Between. It didn’t faze me. Everyone cheered, and then my father said: ‘That was my daughter.’ It was thrilling.”

When the Second World War broke out, her father joined up as a private and was away from the family for seven years. As a result Celia became the family breadwinner. She sang to 2,000 troops at the Albert Hall, to severely disfigured men at the burns unit in East Grinstead, to the forces on the European front and at RAF hangars across the country, becoming known for Maybe It’s Because I’m A Londoner and You’ve Got Your Own Life To Live. With her mother as chaperone she toured Britain.

Her greatest triumphs, though, were her appearances as Peter Pan at the Scala Theatre, Tottenham Court Road, in 1943 and 1944 (the “best ever seen in a London theatre” according to one critic), and in Lionel Monckton’s 1944 revival of the light opera, The Quaker Girl, when she stepped in for Jessie Matthews at the last moment and received a dozen curtain calls on opening night at the Coliseum.

After the war Celia Lipton travelled to Paris and then the French Riviera where, on one occasion, she met the young Prince Philip of Greece, who offered to escort her to the casino in Cannes. “I asked him how we were going to get there and he said he’d borrowed a man’s bike and he put me on the back of it,” she recalled in 2004. “My dress kept catching in the back of the bike. I was lucky since I got to dance with him. He was an exceptionally good dancer.”

She also launched herself on a film career. After making her debut supporting John Bentley and Dinah Sheridan in Calling Paul Temple (1948), she appeared opposite Sonia Dresdel and Walter Fitzgerald in the adaptation of Joan Morgan’s novel, This Was A Woman (1948) and played Sandra in Terrence Young’s melodrama The Frightened Bride (1952).

In 1952 Celia Lipton moved to New York, where she joined the all-star revue, John Murray Anderson’s Almanac (1953-54) at the Imperial Theatre, Broadway, and appeared as Esmeralda to Robert Ellenstein’s Quasimodo in a television version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1954).

While in New York, she met Victor Farris. “I was returning some books to a friend and there was a man up on a ladder fixing a fan – my future husband,” she recalled. At first she thought he was a plumber and then, maybe, a member of the Mafia. In fact he owned 17 companies, was the inventor of the paper milk carton, the paper clip and the Farris Safety and Relief Valve, still used in shipping, oil and chemical industries. He was also a millionaire many times over. The couple wed in 1956, with Celia giving up showbusiness to devote herself to married life in New Jersey and, later, Florida.

Although the marriage was not without its difficulties — her relationship with her husband was sometimes volatile and Celia suffered ten miscarriages and gave birth prematurely to two babies who both died within a week — it was a happy one. At their sumptuous mansion in Palm Beach, once owned by the Vanderbilts, Celia became a leading society hostess.

When Victor Farris died of a heart attack in 1985, closely followed by her parents, Celia’s life altered dramatically again. Her husband had left her his £100 million fortune (an amount she more than doubled through shrewd investments over subsequent years), and she embarked on a new phase of her life as a philanthropist and charity fundraiser. “There are a lot of silly, socially competitive, frivolous women in this town who gossip, go out to lunch every day and dinner every night and that’s it,” she observed. “I’m delighted that I know what hard work is and proud of my Scottish mother and the good Scottish common sense she taught me.”

A convert to Catholicism, she raised large sums for the Salvation Army, the American Heart Association and cancer research charities. At a time when the disease was taboo she was one of the first big private benefactors of Aids research. Other beneficiaries included the National Trust for Scotland, the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital, the American Red Cross, the Prince’s Trust and the Duke of Edinburgh Trust.

In addition she became Executive Producer of the American Cinema Awards in Hollywood (which raises funds for actors who have fallen on hard times); sang before the Queen at the 50th anniversary of VE Day in Hyde Park, made a brief screen comeback with Burt Reynolds in BL Stryker (1989-1990), and released a series of her own, self-financed, CDs. In 2008, she published her autobiography My Three Lives.

With her big stack of silvery-blonde hair, pillar-box red lipstick and tailored white suits, Celia Lipton retained the looks of a 1940s star. She lived surrounded by framed — often signed — thank you letters and photographs featuring Elizabeth Taylor, Sophia Loren, Bob Hope, Douglas Fairbanks Jr, Frank Sinatra, Whitney Houston, Pope John Paul II, Diana, Princess of Wales, and even John Major.

In her autobiography Celia Lipton related that she was “honoured to receive a letter informing me that Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth had appointed me a Dame”, conveying the impression that she had been created DBE. In fact, in 2004 she was named a Dame of Grace of the Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem, entitling her to place the letters D St J after her name. Nonetheless she headed her personal notepaper, Dame Celia Lipton Farris, and, in America, was announced by that style on social occasions.

She is survived by two adopted daughters