John Hurt obituary in “The Guardian” in 2017

Few British actors of recent years have been held in as much affection as Sir John Hurt, who has died aged 77. That affection is not just because of his unruly lifestyle – he was a hell-raising chum of Oliver Reed, Peter O’Toole and Richard Harris, and was married four times – or even his string of performances as damaged, frail or vulnerable characters, though that was certainly a factor. There was something about his innocence, open-heartedness and his beautiful speaking voice that made him instantly attractive.

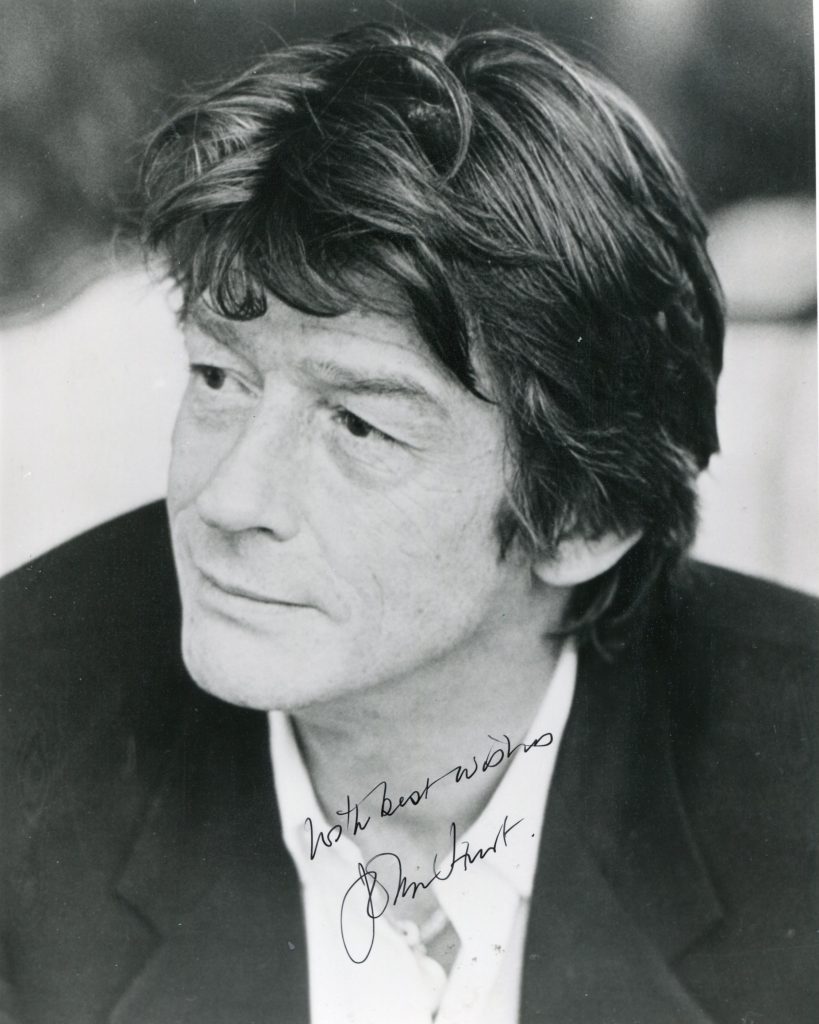

As he aged, his face developed more creases and folds than the old map of the Indies, inviting comparisons with the famous “lived-in” faces of WH Auden and Samuel Beckett, in whose reminiscent Krapp’s Last Tape he gave a definitive solo performance towards the end of his career. One critic said he could pack a whole emotional universe into the twitch of an eyebrow, a sardonic slackening of the mouth. Hurt himself said: “What I am now, the man, the actor, is a blend of all that has happened.”

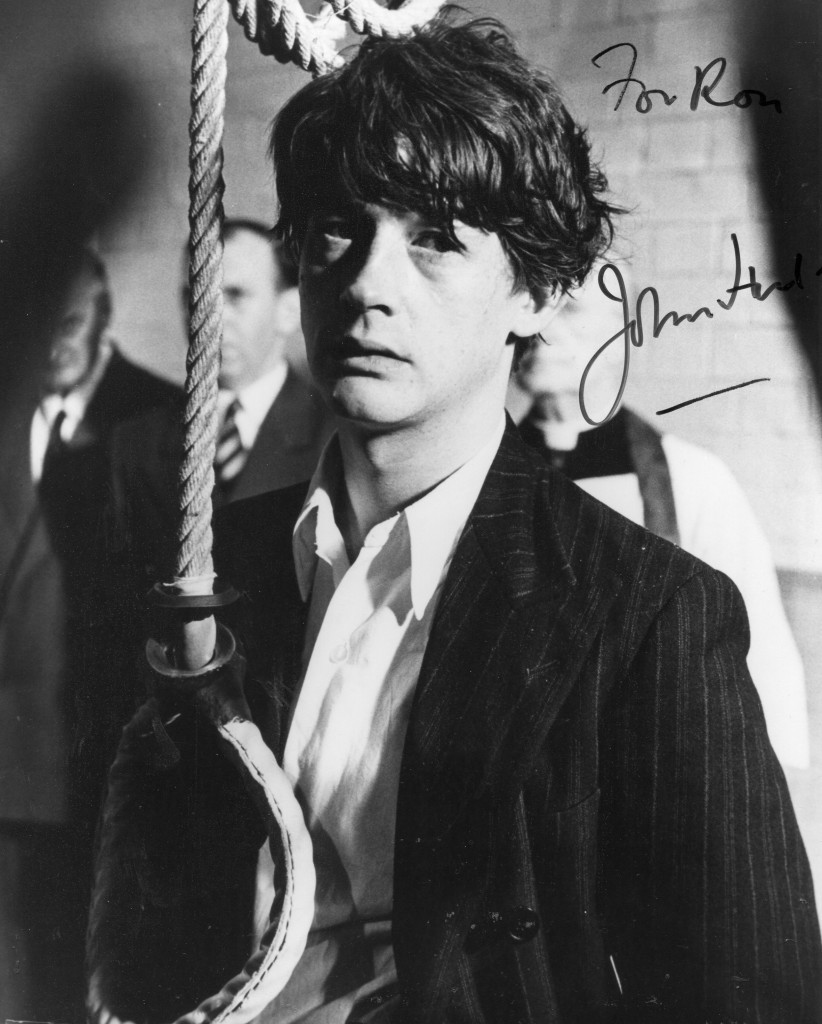

For theatregoers of my generation, his pulverising, hysterically funny performance as Malcolm Scrawdyke, leader of the Party of Dynamic Erection at a Yorkshire art college, in David Halliwell’s Little Malcolm and His Struggle Against the Eunuchs, was a totemic performance of the mid-1960s; another was David Warner’s Hamlet, and both actors appeared in the 1974 film version of Little Malcolm. The play lasted only two weeks at the Garrick Theatre (I saw the final Saturday matinée), but Hurt’s performance was already a minor cult, and one collected by the Beatles and Laurence Olivier.

He became an overnight sensation with the public at large as Quentin Crisp – the self-confessed “stately homo of England” – in the 1975 television film The Naked Civil Servant, directed by Jack Gold, playing the outrageous, original and defiant aesthete whom Hurt had first encountered as a nude model in his painting classes at St Martin’s School of Art, before he trained as an actor.

Crisp called Hurt “my representative here on Earth”, ironically claiming a divinity at odds with his low-life louche-ness and poverty. But Hurt, a radiant vision of ginger quiffs and curls, with a voice kippered in gin and as studiously inflected as a deadpan mix of Noël Coward, Coral Browne and Julian Clary, in a way propelled Crisp to the stars, and certainly to his transatlantic fame, a journey summarised when Hurt recapped Crisp’s life in An Englishman in New York (2009), 10 years after his death.

Hurt said some people had advised him that playing Crisp would end his career. Instead, it made everything possible. Within five years he had appeared in four of the most extraordinary films of the late 1970s: Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), the brilliantly acted sci-fi horror movie in which Hurt – from whose stomach the creature exploded – was the first victim; Alan Parker’s Midnight Express, for which he won his first Bafta award as a drug-addicted convict in a Turkish torture prison; Michael Cimino’s controversial western Heaven’s Gate (1980), now a cult classic in its fully restored format; and David Lynch’s The Elephant Man (1980), with Anthony Hopkins and Anne Bancroft.

In the last-named, as John Merrick, the deformed circus attraction who becomes a celebrity in Victorian society and medicine, Hurt won a second Bafta award and Lynch’s opinion that he was “the greatest actor in the world”. He infused a hideous outer appearance – there were 27 moving pieces in his face mask; he spent nine hours a day in make-up – with a deeply moving, humane quality. He followed up with a small role – Jesus – in Mel Brooks’s History of the World: Part 1 (1981), the movie where the waiter at the Last Supper says, “Are you all together, or is it separate checks?”

Hurt was an actor freed of all convention in his choice of roles, and he lived his life accordingly. Born in Chesterfield, Derbyshire, he was the youngest of three children of a Church of England vicar and mathematician, the Reverend Arnould Herbert Hurt, and his wife, Phyllis (née Massey), an engineer with an enthusiasm for amateur dramatics.

After a miserable schooling at St Michael’s in Sevenoaks, Kent (where he said he was sexually abused), and the Lincoln grammar school (where he played Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest), he rebelled as an art student, first at the Grimsby art school where, in 1959, he won a scholarship to St Martin’s, before training at Rada for two years from 1960.

He made a stage debut that same year with the Royal Shakespeare Company at the Arts, playing a semi-psychotic teenage thug in Fred Watson’s Infanticide in the House of Fred Ginger and then joined the cast of Arnold Wesker’s national service play, Chips With Everything, at the Vaudeville. Still at the Arts, he was Len in Harold Pinter’s The Dwarfs (1963) before playing the title role in John Wilson’s Hamp (1964) at the Edinburgh Festival, where the critic Caryl Brahms noted his unusual ability and “blessed quality of simplicity”.

This was a more relaxed, free-spirited time in the theatre. Hurt recalled rehearsing with Pinter when silver salvers stacked with gins and tonics, ice and lemon, would arrive at 11.30 each morning as part of the stage management routine. On receiving a rude notice from the distinguished Daily Mail critic Peter Lewis, he wrote, “Dear Mr Lewis, Whooooops! Yours sincerely, John Hurt” and received the reply, “Dear Mr Hurt, Thank you for short but tedious letter. Yours sincerely, Peter Lewis.”

After Little Malcolm, he played leading roles with the RSC at the Aldwych – notably in David Mercer’s Belcher’s Luck (1966) and as the madcap dadaist Tristan Tzara in Tom Stoppard’s Travesties (1974) – as well as Octavius in Shaw’s Man and Superman in Dublin in 1969 and an important 1972 revival of Pinter’s The Caretaker at the Mermaid. But his stage work over the next 10 years was virtually non-existent as he followed The Naked Civil Servant with another pyrotechnical television performance as Caligula in I, Claudius; Raskolnikov in Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment and the Fool to Olivier’s King Lear in Michael Elliott’s 1983 television film.

His first big movie had been Fred Zinnemann’s A Man for All Seasons (1966) with Paul Scofield (Hurt played Richard Rich), but his first big screen performance was an unforgettable Timothy Evans, the innocent framed victim in Richard Fleischer’s 10 Rillington Place (1970), with Richard Attenborough as the sinister landlord and killer John Christie. He claimed to have made 150 movies and persisted in playing those he called “the unloved … people like us, the inside-out people, who live their lives as an experiment, not as a formula”. Even his Ben Gunn-like professor in Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008) fitted into this category, though not as resoundingly, perhaps, as his quivering Winston Smith in Michael Radford’s terrific Nineteen Eighty-Four (1984); or as a prissy weakling, Stephen Ward, in Michael Caton-Jones’s Scandal (1989), about the Profumo affair; or again as the lonely writer Giles De’Ath in Richard Kwietniowski’s Love and Death on Long Island.Advertisement

His later, sporadic theatre performances included a wonderful Trigorin in Chekhov’s The Seagull at the Lyric, Hammersmith, in 1985 (with Natasha Richardson as Nina); Turgenev’s incandescent idler Rakitin in a 1994 West End production by Bill Bryden of A Month in the Country, playing a superb duet with Helen Mirren’s Natalya Petrovna; and another memorable match with Penelope Wilton in Brian Friel’s exquisite 70-minute doodle Afterplay (2002), in which two lonely Chekhov characters – Andrei from Three Sisters, Sonya from Uncle Vanya – find mutual consolation in a Moscow café in the 1920s. The play originated, as did that late Krapp’s Last Tape, at the Gate theatre in Dublin.

His last screen work included, in the Harry Potter franchise, the first, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001), and last two, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Parts One and Two (2010, 2011), as the kindly wand-maker Mr Ollivander; Rowan Joffé’s 1960s remake of Brighton Rock (2010); and the 50th anniversary television edition of Dr Who (2013), playing a forgotten incarnation of the title character.

Because of his distinctive, virtuosic vocal attributes – was that what a brandy-injected fruitcake sounds like, or peanut butter spread thickly with a serrated knife? – he was always in demand for voiceover gigs in animated movies: the heroic rabbit leader, Hazel, in Watership Down (1978), Aragorn/Strider in Lord of the Rings (1978) and the Narrator in Lars von Trier’s Dogville (2004). In 2015 he took the Peter O’Toole stage role in Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell for BBC Radio 4. He had foresworn alcohol for a few years – not for health reasons, he said, but because he was bored with it.

Hurt’s sister was a teacher in Australia, his brother a convert to Roman Catholicism and a monk and writer. After his first marriage to the actor Annette Robinson (1960, divorced 1962) he lived for 15 years in London with the French model Marie-Lise Volpeliere Pierrot. She died in a riding accident in 1983.

In 1984 he married, secondly, a Texan, Donna Peacock, living with her for a time in Nairobi until the relationship came under strain from his drinking: they divorced in 1990. With his third wife, Jo Dalton, whom he married in the same year, he had two sons, Nick and Alexander (“Sasha”); they divorced in 1995. In 2005 he married the actor and producer Anwen Rees-Myers, with whom he lived in Cromer, Norfolk. Hurt was made CBE in 2004, given a Bafta lifetime achievement award in 2012 and knighted in the New Year’s honours list of 2015.

He is survived by Anwen and his sons.