Bobby Henrey

Bobby Henrey gave one of the best performances by a child ever on film in Carol Reed’s classic “The Fallen Idol” in 1948. He was born in France in 1939. His mother was the author Madeleine Henrey and he was cast in the film after his photograph was noticed in one of his mother’s books. He went on to make “The Wonder Kid” in 1951. He did not pursue an acting career and went to live in the U.S. where be became a chaplain.

“Guardian” article from 2001 by : Claire Armitstead

Bobby Henrey was a lonely child. French was his first language, but he spent the second world war in a flat in Piccadilly, at the heart of a blitzed city emptied of other children. His parents were writers, and the cover of one of their books featured a picture of their pretty blond son looking out of their window on the ruins of London.

It might all have ended there, had the picture not been spotted by film producer Alexander Korda, who was looking for a little Francophone boy to star in an adaptation of Graham Greene’s short story The Basement Room.

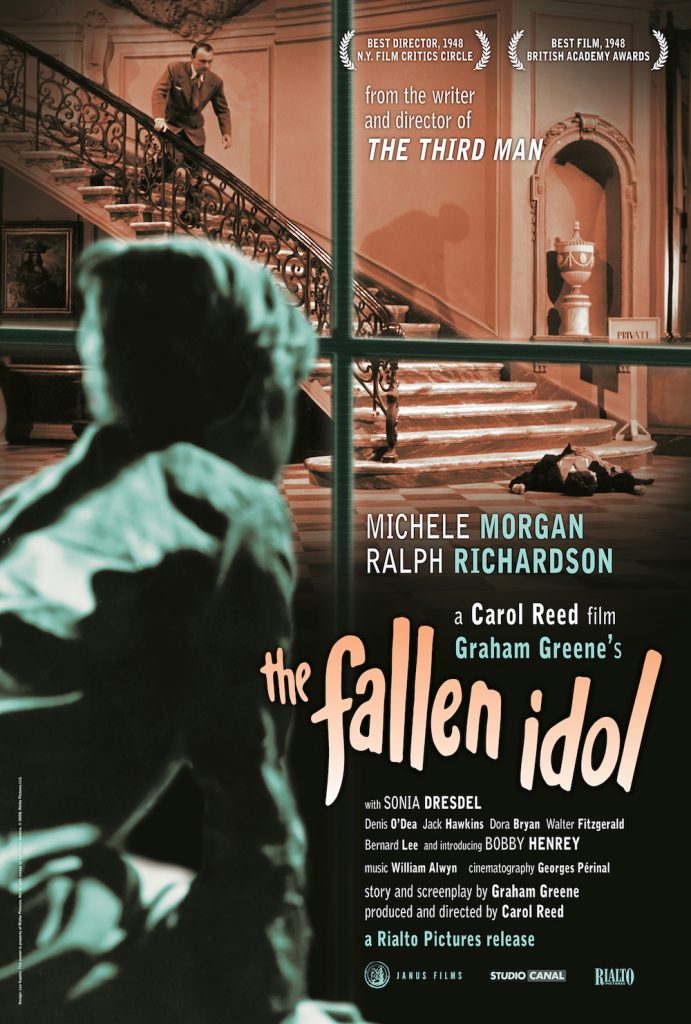

The film, retitled The Fallen Idol, was released in 1948, the first of three collaborations between Greene and director Carol Reed, and has just been restored by the British Film Institute. According to David Hare, one of the donors who helped finance the restoration, “It’s a great, overlooked masterpiece of the British cinema. The more you read about Reed, the more you realise that he is our William Wyler – the director who seems able effortlessly to go to the heart of his subject, without ever drawing attention to himself. He just knows where the story should go, and that’s the rarest gift of all in cinema.”

Reed and Korda are long dead, but gathered for the recent premiere of the new print were three people whose lives were indelibly marked by the film: Bobby, the actress Dora Bryan, and Reed’s assistant director Guy Hamilton, who was embarking on a career that would include a raft of Bond movies.

Part of Hamilton’s job was to coax a performance out of Bobby, who was more interested in watching what the electricians were up to than in playing to the camera. Bobby was not a stage school brat; he belonged to that other tradition of child actor most commonly associated with realist directors such as Bill Douglas or Ken Loach – where the film-maker’s art is to observe a child being a child.

“Bobby had the concentration of a demented flea,” says Hamilton. “Carol and I would play good cop, bad cop. I could shout at him, but Carol could never lose his temper, even though the sweat would be pouring down his face. He would film six or seven hundred feet of film just to get one line.”

Reed was also a very good observer. One day he watched Bobby playing with a piece of string, and encouraged him to do it again on film. This little, spontaneous action becomes a defining part of the character of the lonely boy.

In the Greene short story, the child is English: Philip, only son of rich absentee parents, betrays his beloved butler to the police for the murder of his shrewish wife, who goes beserk when she discovers he is having an affair. The story is narrated with the hindsight of 60 years, during which the boy has become a shrunken shadow of what he might have been had the twisted passions of the adult world not been forced on him so young.

In the film, there is no such hindsight. There is no murder either, but an accident, which the child – here the son of the French ambassador – misinterprets because he has been enlisted in adult deceptions but is too young to understand what he is being asked to cover up. In one of those alchemical transformations that marks out a great screen adaptation, it becomes a thriller of partial vision – of sight without understanding, fact without truth.

All these are embodied in the fidgety eight-year-old, who, quite literally in cinematic terms, belongs to a different world from the adults he tries to help. There is a dazzling moment when he looks through the distorting window panes of a tea shop at wasps on racks of iced cakes and pulls a face, as if he is trying to become one of them. Seconds later, he glimpses his mentor, played by Ralph Richardson, having tea with his lover in a corner and the deception begins.

For David Hare, “the scene between the lovers in the tea shop is the most painful image of repressed love in the British cinema – the way they fiddle with the cakes and stare into each other’s eyes is infinitely more moving than anything in Brief Encounter. Richardson’s desperate vulnerability and his desire not to let himself down in the child’s eyes is very profound. It’s Freud, of course – Graham Greene as lost child, lost believer, wanting to tell the truth and fearing its power.”

All this responsibility for a child actor who did not act – who was so clueless, in fact, that one weekend, in the middle of shooting a key scene, he went off for a haircut. That meant a two week delay in filming while his hair grew back, and some useful extra work for Bryan, who had been hired for a day’s work as a tart with a heart down at the local nick. The Fallen Idol was her second film – a promotion from “two giggling girls in phone box” and it gave her a show-stealing line, to the little boy clutched to her bosom: “Oh, I know your daddy.”

Bryan says she knew at the time that this wasn’t a “run-of-the-mill film”. But Reed was not so sure, Hamilton recalls: “He was very worried because he realised Bobby Henrey was the star, and if the audience didn’t warm to him, the whole thing would turn to seaweed. And Bobby was a very odd little boy, quite effeminate, French, not a little Anthony Newley.”

He invited Hamilton to watch an early cut: “I thought it was a disaster – a two hour, 25 minute pudding.” Only in the cutting room did what Hamilton describes as “this miraculous child performance” begin to emerge. Not that Henrey was aware of any of it. He went on to make one other “attrocious” film, Karl Hartl’s The Wonder Kid, before being sent off to boarding school.

His only subsequent brush with showbusiness was when, as a student at Oxford, he was invited to appear on Bryan’s This Is Your Life. He spent his career as an accountant in America, before retiring to work as a hospital chaplain in Greenwich Village. Now in his 60s, he is the same age as the older, ruefully retrospective Philip in the short story. It’s not lost on Henrey that there is a certain symmetry between Greene’s fiction and his life.

“There’s a little comment in a film book I once read describing the child as restless intelligence personified. I saw that as rather descriptive of how I am. I think the film also recognised the feelings of isolation that I had. When I went to school I was teased, of course. It continued to be quite a difficult thing to live with until quite recently. It wasn’t tragic, but it wasn’t fun.”

He didn’t know he was in at the birth of the tilting camera, and had no idea he was co-starring with one of postwar England’s most celebrated actors. Indeed, wherever possible, his scenes with Richardson were filmed with Hamilton padded up as a body double. But he does remember the cinematographer Georges Perinal, who was the Rembrandt of cinema lighting. “He used little fingers of cardboard to influence the way the light fell. They were on tripods, and I was fascinated by them. I haven’t thought about that for 50 years.”

The above “Guardian” article can also be accessed here.