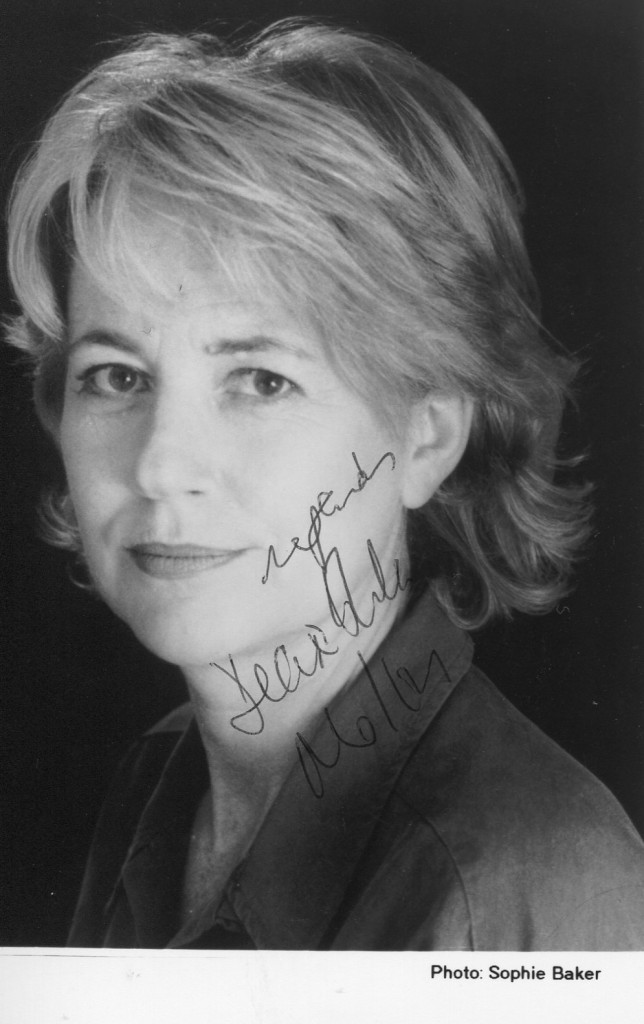

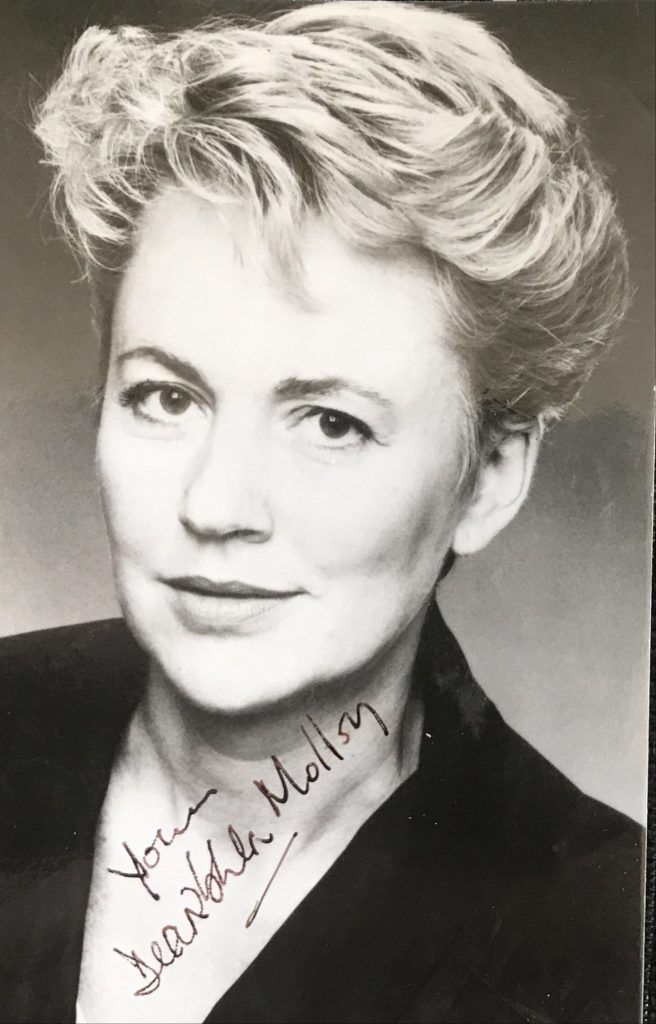

Dearbhla Molloy was born in 1946 in Dublin. She has acted on the London stage with the Royal Shakespeare Company. In 1991 she was part of the cast of Brian Friel’s play “Dancing at Lughnasa” which won rave reviews in Dublin, London and on Broadway. On “Coronation Street” she plasy the part of Michele Connor’s mother, Her films include “Tara Road”, “This is the Sea” and “The Blackwater Lightship” with Angela Lansbury. She has guest starred in British televison dramas like “Foyle’s War”, “New Tricks” and “Waking the Dead”.

Article in 2007 in “Independent.ie”:

It’s rare for an attractive single woman to admit to having examined her conscience to see if she had secretly been expecting some well-heeled suitor to turn up and take

care of her, but actress Dearbhla Molloy is searingly self-critical. She talks to Patricia Deevy about miracles, men, hair colour and financial meltdown.

AFTER Phaedra, Dearbhla Molloy swore she wouldn’t be back. “I’m a socialist meself and I’m quite happy to pay tax, but they used to take it off at super-rate on the piddly amount that the Gate paid you. I ended up paying for myself to do Phaedra. It took me about two years to get over it.”

She even swore off doing theatre. After she turned 50 she decided she must concentrate on earning a pension. But here she is, six months out of playing Juno in London’s Donmar Warehouse, preparing to be Bessie Burgess in The Plough and the Stars at the Gaiety, before returning to Juno for a summer run in New York.

I suppose that theatre won’t subsidise the four-week break between the Dublin and New York runs. She all but snorts: “Theatre! Do you know how much we earn a week during rehearsals? Two hundred and fifty pounds before tax, insurance and you pay your agent. So you get about £130 home. What does it pay for your groceries? That’s why I swore I wasn’t going to do any more.”

But Molloy is not a great planner. Her choice of work is guided by her heart rather than her balance sheet and a Plough directed by Stephen Rea was irresistible. (Incidentally, last time she did the Plough she played Mrs Gogan opposite one great friend, Judi Dench, and was directed by another friend, Sam Mendes. She had played in Mendes’ debut production. “And then he came to live with us. We lent him the spare room. I’ve known him since he was 23 so he’s like my son.”)

Molloy’s reasons for taking on this production are complicated something to do with wanting to plug into Irish history in the making. “In England, I do feel at one remove from what’s happening with the peace process. So Stephen’s idea about this play about trying to shake it out of the accepted, expected way of doing it and trying to make visible and present that journey between 1916 and where we are now was something that appealed to me hugely.”

She is “groping” towards a contemporary understanding of Bessie Burgess, the defiant singer of Rule Britannia and robust Protestant hymns while the 1916 Rising swells around her.

“She is terrified of the fact that the old order is disappearing. What’s she going to do? She’s going to be surrounded and run by Shinners, people that she’s hated. If I could get that into her that it’s all sorts of orders crumbling, the external order but also the internal order.

“I could be scared about it. I never saw myself as Bessie Burgess. But one of the great things that Judi Dench said to me was: `If somebody else thinks you can do it, do it.’

“I would never have thought myself I could do it, but the fact that Stephen thinks I can and the fact that Noel [Pearson, the show’s producer] thinks I can and I trust and like both.”

For a woman with a full CV, impeccable reviews and a well-deserved reputation as one of Ireland’s finest actors, these are modest sentiments. But Molloy has a modest way about her. Her interview demeanour is serious and sober because the subjects often are; to say that we talk about the meaning of life and of death is not a loose generalisation but a precise description. However, the other side also emerges: one which is fuelled by a raucous laugh and lit up by a dazzlingly mischievous smile. For all her earnestness, Molloy is no navel-gazing artiste.

Molloy’s training in acting was “just doing it”. After doing her Leaving Cert at 16, drama was the only option which appealed to her. She took courses at the Brendan Smith Academy alongside people like Anita Reeves and John Kavanagh. Later, Ray McAnally gave her voice lessons to help overcome a lisp. Later still, at 40, realising anew that acting was going to be her life for the rest of her life, she went to her friend Dench to learn to speak verse.

There was nothing in her background to send her to the stage except spirit. The eldest of seven, she grew up in Malahide and was always straining at the boundaries of propriety. She asked questions in an era when schoolgirls didn’t. Her questions were logical, like why were girls responsible for sexuality: “Boys couldn’t help it but girls could help it. And I found that profoundly offensive and I challenged that.

“All sorts of things were stirring that were being met by ancient auld bachelor priests whose answer to your question was, `That’s not a suitable question.’ My belief was that wasn’t a suitable answer, but then you were regarded as being cheeky and being difficult. I was expelled from two schools. I think it was that, that stopped me being a Catholic: not being respected and not being met at where I was at.”

She rediscovered religion, if not belief, in an ironic way. At 21 she married another actor, Bobby Carlisle. “I married as a way out, as an escape, for sure. Now I see exactly what I did, but then I didn’t. You don’t.” Carlisle was an alcoholic, and five years and one son later they separated. She went about getting a divorce in England and, although no longer Catholic, a church annulment in Ireland.

THROUGH the mid- and late Seventies, she worked between Ireland and England, and the annulment procedure trundled in the background. Though she didn’t know it then, going to England as Mibs in Hugh Leonard’s A Life in 1979 marked her final departure from Ireland. Job after job came her way, and before she knew it she’d been there three years. Rory, her son, lived with her parents and went to school in Malahide.

As part of the annulment procedure she was appointed a devil’s advocate. She doesn’t remember his name. “He was absolutely gorgeous. You’d fall in love with him. I didn’t fall in love with him because he kept challenging me, I fought like a cat with him. He wasn’t some old fogey, the kind of priest that I rebelled against. You couldn’t dismiss him. He was highly educated. He was a smart, sophisticated man.”

The cleric’s approach was as intense and demanding as analysis and she learned to embrace its challenges and what they could teach her about herself. “It’s like somebody with a mirror running around after you all the time saying: `Look in here and tell me what you see.’ And you might have been going along saying, `I have brown eyes,’ and they just say, `Look again, what do you see?’ They don’t say, `No, no, they’re blue.’ They just keep asking you what you see.

“It [the annulment] affected the whole of the rest of my life. I would have gone unconsciously onwards. It was like being forced to face in a different direction.”

Shortly after splitting with Bobby Carlisle, Molloy began a relationship with the director Brian de Salvo and she later married him. They split up 10 years ago and were divorced in 1995. Carlisle died at 40 after a heart attack.

The self-scrutiny prompted by the annulment process led Molloy to scale back her acting in her mid-30s and to train as a psychotherapist. She didn’t qualify because she never took on clients, but the process is now a part of her life. On a recent American trip she took a course in family systems. One of her tutors gave her an article on Irish-Americans.

“A lot of the things that I thought were purely personal to me, I now found are just part of my ethnic gene pool. Things like I’m not one of those people who at the end of a long-term relationship can then convert the person into a friend. I just cut them off stone-dead and never see them again. Not with any animosity: it’s just that that’s the end of that. It’s an Irish thing, seemingly.

“What else? The fact that we like to word play and we like ambiguity, and very often you’ll sense what I’m saying not because of the words that I use but because of what’s behind the words that I use. I lived with an Englishman for 20 years and we missed a lot of the time. I used to eventually say: `What do you think I’m saying? Tell me what you hear me say.’ And then he would say it and that would not be what I was saying even though I could see how he could hear it that way.”

As a twice-divorced single woman in her mid-50s, life makes demands on Dearbhla Molloy. A big one is facing financial vulnerability. “I don’t have any insurance policies and I don’t have a pension plan and any of that. I’m kind of hesitant about saying this but to the best of my ability to be responsible, I really believe that I’ll always be all right and I always have been all right.”

Two years ago, she had a financial meltdown. After doing two years’ theatre work, but living as if she was earning good money, she realised there was very little left in the bank.

“I was very frightened for about three days and then I thought: `Well, what’s the worst that could happen?”’

She examined her conscience to see if secretly she had been expecting some well-heeled suitor to turn up and take care of her, and having decided that was not the case, she was able to move on. “Just getting to that bottom level really made me look at where I was around trusting the universe. I decided I had nothing to lose and everything to gain just by saying: `OK, I believe that I’ll be fed and clothed and taken care of.’ And I have to say, it may sound ridiculous, but miracles have occurred. Things have presented themselves at exactly the right moment.

“I buy classic clothes that last for a long time and I don’t care. It’ll be cashmere but I’ll wear it until it’ll have a hole in the elbow and I don’t mind if it has a hole. I quite like that. And I’m sitting here in Armani jeans, but they’ll last me four years or whatever. In fact I have very few clothes. My wardrobe is about that wide [her open palms span a distance of hardly three feet] and I just wear them over and over again.”

The only advice she’s ever given her son is based on her hard-won wisdom: “For God’s sake get your income tax sorted out.” (After going to art college in Limerick, Rory moved to London and now they live in the same square near London Bridge. He is 31 and works in music of the modern electronic variety.)

For Molloy money is deeply significant. She grew up with a Labour-supporting father and a belief in helping the less well-off. For a long time how to share troubled her so she decided to tithe her income. One-tenth of whatever she earns goes into a special charities bank account. “Sometimes they [the charities] get a lot and sometimes they get very little, but it keeps me straight. I couldn’t cope with it: I was really getting stressed about whatever the thing is about being selfish and being responsible towards the other, and trying to be responsible towards yourself.”

This agonising also pervades her attitude to ageing. She thinks she is comfortable with her age of 54. But then she’s not sure. “I think: `Am I going to let my hair grow white? Am I going to have it dyed out of vanity or am I going to have it dyed because I prefer what I look like? Am I going to have it dyed because I want to pretend I’m not the age I am?’ So therefore I wildly overcompensate: I busily tell everyone what age I am. Maybe it’s in the hope that they’ll say: `My God, you don’t look it at all.’ So it’s a bit of a mess really.”

It sounds to me that she may have lost the religion, but she has retained that old-style self- lacerating way of thinking. She laughs wryly: “That’s right. I must be searingly honest. Scorch-your-soul honest. Why not think: `I look better with dyed hair so I’m dying my hair?”’

In the 10 years since she split with Brian de Salvo, Molloy hasn’t had a significant romantic relationship. “I don’t know whether that’s me or whether it’s just not there. I don’t know whether it’s a function of the age I am, ’cause most men of 50 want 35-year-olds. I’ve got past the stage of thinking it’s because I’m invisible or not attractive, because I attract young men, but they’re not suitable permanent candidates or the ones that I attract are not.”

She sees now that in the past she was the archetypal victim in her relationships with men, that she allowed and expected them to dominate her. But what is common in the good marriages she sees in her circle is that people live with their best friends. “Whereas I have to say I never had a relationship with my best friend, it was always based on something else.”

BUT she is a “fundamentally contented person”, so meeting a man is not a priority. If anything, psychological integration is what she holds sacred. “I have absolutely no doubt whatsoever that meaning is to me the most important thing. Meaning, I suppose, converts pain into suffering which elevates it to a kind of graceful state. It’s a kind of pay-off. Meaning is a central, central theme of my life. Maybe I’ve just made a construct which makes me feel safe. I don’t know. But I don’t really care.”

The above “Independent.ie” article can also be sourced online here.