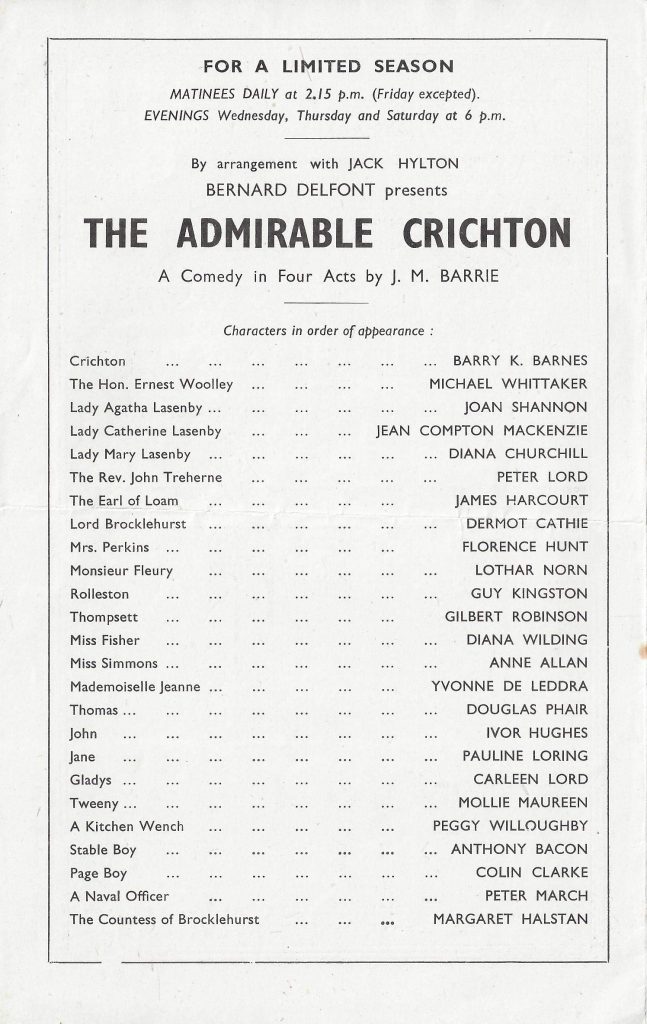

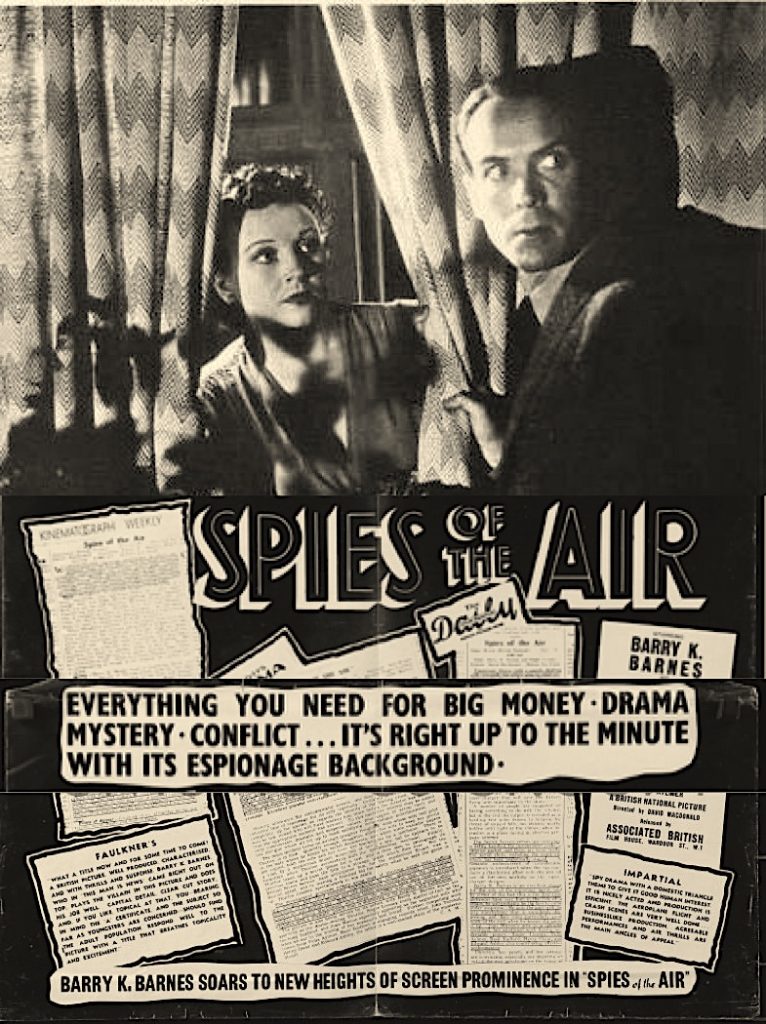

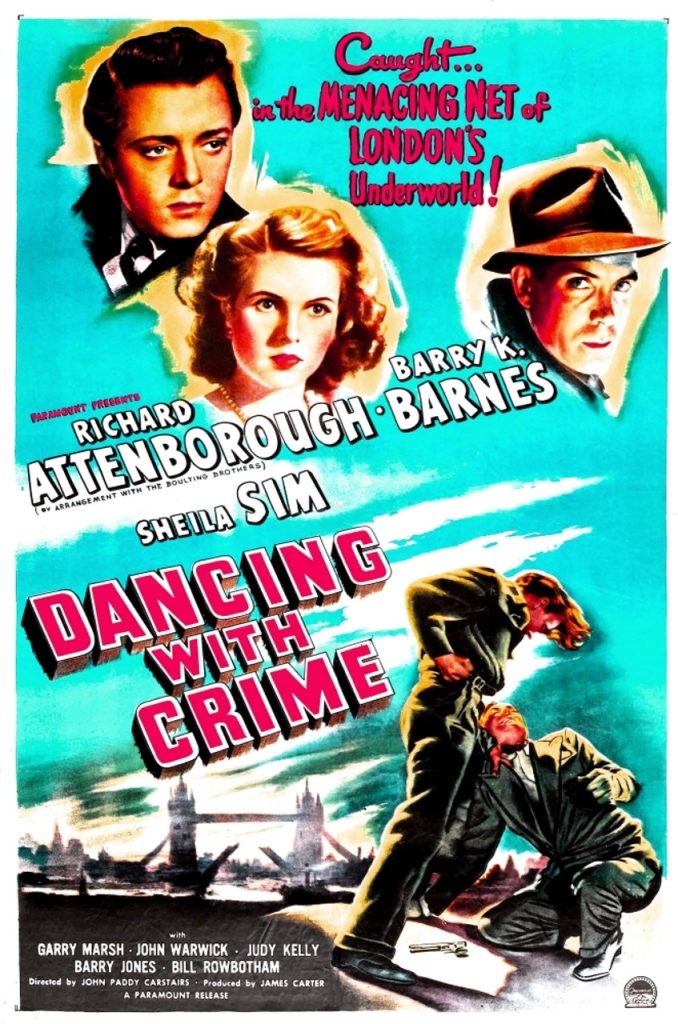

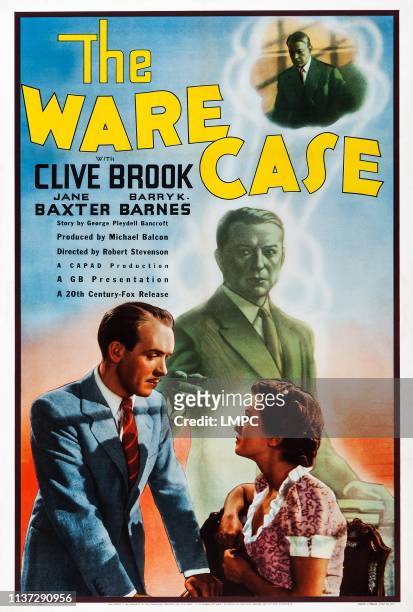

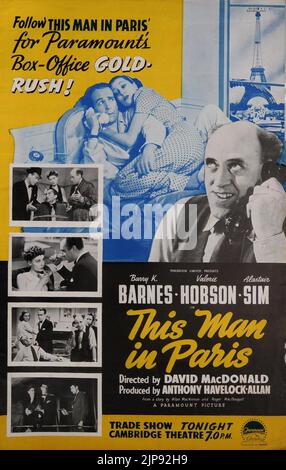

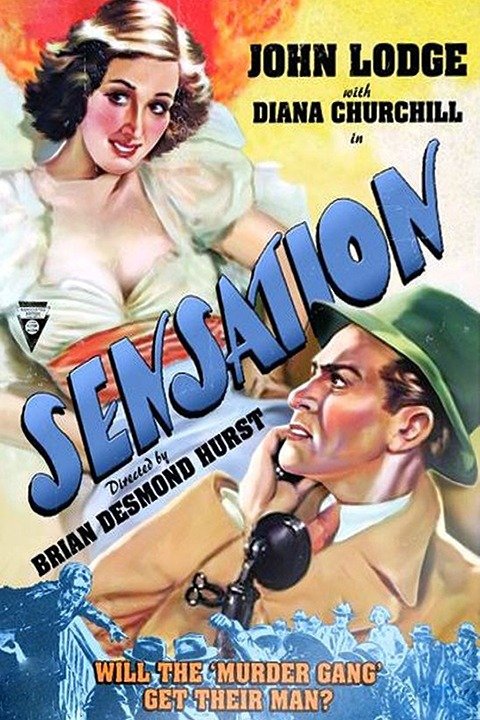

Diana Churchill was born in 1913 in London. Her first film was in 1932 and was called “Service for Ladies”. She also made “School for Husbands”, “Scott of the Antartic”, “The History of Mr Polly” and “The Winter’s Tale”. She died in Mississipi in 1994. Barry K. Barnes was born in 1906 in London. Some years after the death of her husband Barry K. Barnes she married Melvyn Johns, the father of Glynis Johns. “Dodging the Dole” in 1936 was his first film. Other films include “This Man Is News”, “Bedelia” with Margaret Lockwood in 1946. He died in 1965.

IMDB Entry:

Barry K. Barnes was born on December 27, 1906 in London, England as Nelson Barry Mackintosh Barnes. He was an actor, known for Return of the Scarlet Pimpernel (1937),This Man Is News (1938) and Law and Disorder (1940). He was married to Diana Churchill. He died on January 12, 1965 in London.

Diana Churchill’s obituary in “The Independent”:

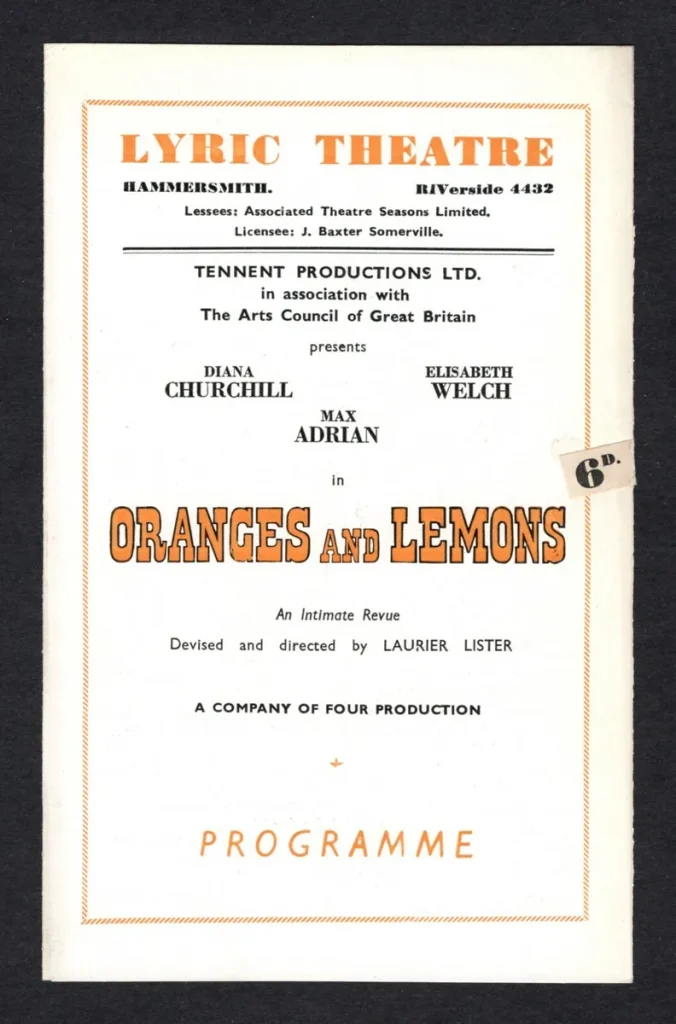

IF EVER there was an actress for all theatrical seasons it was surely Diana Churchill. As brilliant and acerbic in satirical review with Max Adrian or Ian Carmichael (Oranges and Lemons, High Spirits), as she was authoritative in Shakespeare (Gertrude to Alan Badel’s Hamlet, Paulina to Laurence Harvey’s Leontes in The Winter’s Tale) or effervescent in restoration comedy – The Country Wife being, as George Devine put it, the classical revival which in 1956 ‘saved’ the contemporary theatre at the Royal Court Theatre from bankruptcy – she cast a spell on both sides of the footlights for nearly 40 years.

With her large blue eyes, blonde hair, good looks, striking personality and demure charm, she was something of an enchantress from the start, which was at one of those Canterbury Cricket Weeks where the Old Stagers put on light- hearted stuff to while away the evenings, and the 18-year-old Churchill, pretty as a picture, found favour in Coward’s Hay Fever.

Thereafter, though she spent years in fluffy West End comedies and farces before taking her art more seriously, she was never out of work. What made the work so remarkable however, was not only its consistency but its variety.

People may have talked about the Diana Churchill part as if it were definable after her first big hit in the mid-1930s as the uppity young wife in The Dominant Sex, but as time went on and musicals and thrillers and Chekhov and revues came and went it soon became a job to say what the Churchill part was.

What seemed so refreshing about her work was its way of not inciting contempt from her colleagues as might have been expected for such a popular young player. Indeed she was one of the least selfish of her calling and was as much admired for the help she gave to others as for the disciplines she brought to her own performances.

These ranged from hoydens to matrons and heart-broken heroines in scores of forgotten comedies, but what gave her career its unfading quality – until multiple sclerosis struck her down in late middle-age – was her determination to avoid typecasting and her skill at never seeming to be miscast.

Whether as the empty-headed Natasha in The Three Sisters (1951), the eccentric and spectacularly costumed Queen Ant in Under the Sycamore Tree (1952) to Alec Guinness’s Scientist, the dying heroine of Fry’s A Phoenix Too Frequent, prancing wittily and elegantly about at the London Hippodrome in the revue High Spirits (1953), or remonstrating as Emilia with Harry Andrews’s Othello at Stratford, Diana Churchill never seemed to get a hostile notice.

Was her heart more in revue and restoration comedy than classical tragedy? Well, they tend to go together with many players and she was a supremely accomplished comedienne: the glint of mischief in her bright-blue gaze, the warmth of personality, the bubbling high spirits. Yet she could change her tone to the tragic even from sketch to sketch as anyone will avouch who saw her monologue in the 1948 revue Oranges and Lemons as the despairing school marm. With a smile which, as Harold Hobson once put it, was all the sadder for being so serene.

Then there was her partnership in the Forties and Fifties with her actor-husband, the incredibly handsome Barry K. Barnes (who died in 1965), which until his illness looked as if it might develop into one of those famous partnerships which the British theatre makes so much of.

They took West End revivals of The Admirable Crichton and On Approval on profitable tours; and then there was her stint at the Old Vic in Moliere, Turgenev and Goldsmith, only a season or two after its great era under Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson; and a Gertrude at Stratford which Ivor Brown called ‘original and exciting’. ‘She did not provide us with the familiar picture of a complacent bundle of sensuality: here was a woman who realised what she had done and what was stirring in Hamlet’s mind.’

Who could ever forget either her melting into life again as the statue Paulina at the end of Frank Dunlop’s revival of The Winter’s Tale at the Edinburgh Festival? Such stillness, such beauty, such poise almost rivalled the memory of Diana Wynyard’s great performance 14 years earlier. She partnered Badel again in 1961 in Anouilh’s The Rehearsal; and at Chichester in the 1960s she turned again to Shaw as Lady Utterword in Heartbreak House and as Araminta Dench in The Farmer’s Wife.

You need a longish memory to have appreciated Diana Churchill’s range of theatrical magic, which if not cut off in its prime might have given us great pleasure in more recent years.

Even multiple sclerosis though, could not damped her spirits utterly as her colleagues at Denville Hall, the theatrical retirement home, in Northwood, Middlesex, became well aware in the last years.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed here.