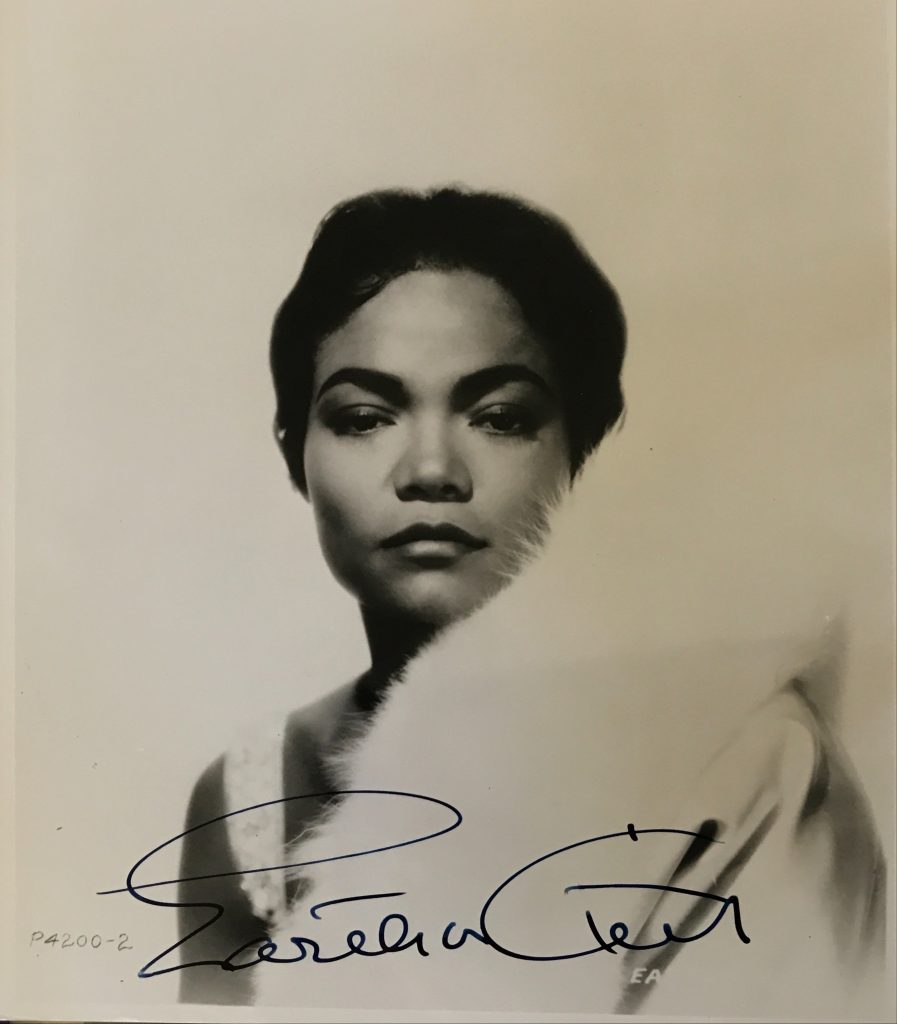

Eartha Kitt was born in South Carolina in 1927. She is forever remembered for the feline quality in her very distinctive voice. Her songs include “Old Fashioned Girl” and “Under the Bridges of Paris”. Her films include “New Faces of 1954” and “Anna Lucasta” in 1958. Eartha Kitt died in 2008 at the age of 81.

Adrian Jack’s “Guardian” obituary:

For six decades, the American entertainer Eartha Kitt, who has died aged 81 of colon cancer, was a showbusiness force of nature. At home, on stage and in the recording studio, and an effective performer on movie and television screens, she made an impact all the greater as an African-American woman breaking new ground.

Her official birth details were established in 1997, when she challenged a group of students to find the certificate that declared her to have been born Eartha Mae Keith in the town of North, South Carolina.

Her father, William Kitt, was a share-cropper in South Carolina and chose the Christian name, it is said, because Eartha was born the year of a good harvest. He left Eartha’s mother, Anna Mae Riley, less than two years later, and the destitute black-Cherokee woman persuaded black neighbours to take in Eartha and her younger half-sister Pearl. Pearl was black and pretty, but Eartha had bushy red hair, which she later dyed, and lighter skin; she was dubbed “that yella gal”.

Eventually, her aunt, Marnie Lue Riley, sent for her and gave her a home in the Puerto Rican-Italian part of Manhattan. Their relationship was difficult, but Eartha had piano lessons paid for as well as savings she knew of only later. She ran away several times, but once she achieved independence, Marnie became mother, and Eartha came to believe that she was really her biological mother.

Down south, Kitt had already impressed the local church congregation with her singing. At school in New York she won respect and popularity with her talent for reading aloud, and she was lucky enough to have teachers who were genuinely interested in her. She also went down well at the local Caribbean dances, where she picked up routines that were to stand her in good stead, not only as a professional entertainer, but also amusing her fellow-workers when she took factory jobs.

Just after her 16th birthday, she auditioned, more or less by accident, for the Katherine Dunham Dance Troupe, whose style was based on Afro-Caribbean folklore. She won a full scholarship to study ballet as well as Dunham’s own technique and her first appearance on Broadway was dancing in Blue Holiday with Ethel Waters and Avon Long. Dunham told “Kitty” she would never make a real dancer because her breasts were too large, but chose her for the troupe which toured the US, Mexico, South America and Europe; increasingly, Kitt took on solo roles, singing as well as dancing, and made her film debut, uncredited, in Casbah (1948).

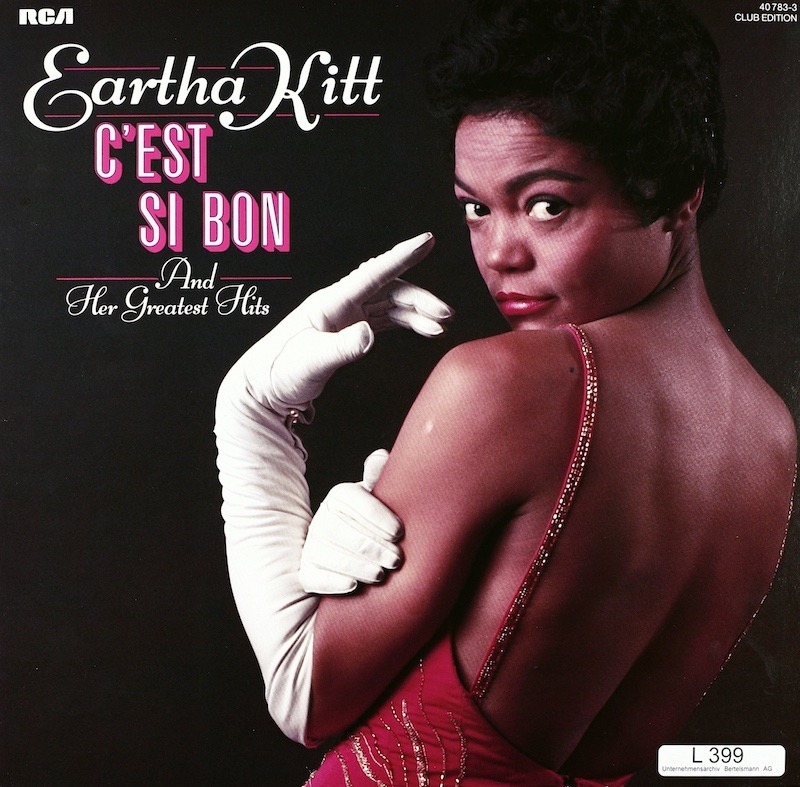

When the Dunham company was in Paris, Kitt was offered her first nightclub engagement at Carroll’s, whose formidable lesbian owner Fred told the waitresses “this one must not be touched”. Kitt later claimed she had no act to speak of at that time, though she had been to the club and seen Juliette Greco’s show. Yet she quickly became a sensation, and when Carroll’s opened a new club, Le Perroquet, the café-au-lait performer was the main attraction, with songs in English, Spanish and French that she prepared with the help of the Cuban bandleader. Singing C’est Si Bon for the first time, she forgot the words and ad-libbed, with such success, she repeated her list of desirables, “mink coat, big Cadillac car” and so on, ever after.

Between the two club engagements, Kitt was cast by Orson Welles as Helen of Troy in his own version of the Faust story, Time Runs, sharing what limelight could be snatched from Welles himself with Michael McLiammoir and Hilton Edwards. If Welles thought her “the most exciting woman in the world”, Kitt later reflected, it was because they never went to bed together. He ate, she watched; he talked, she listened. She was always an admirer of Great Men, and went to considerable lengths to meet Albert Einstein and Jawaharlal Nehru.

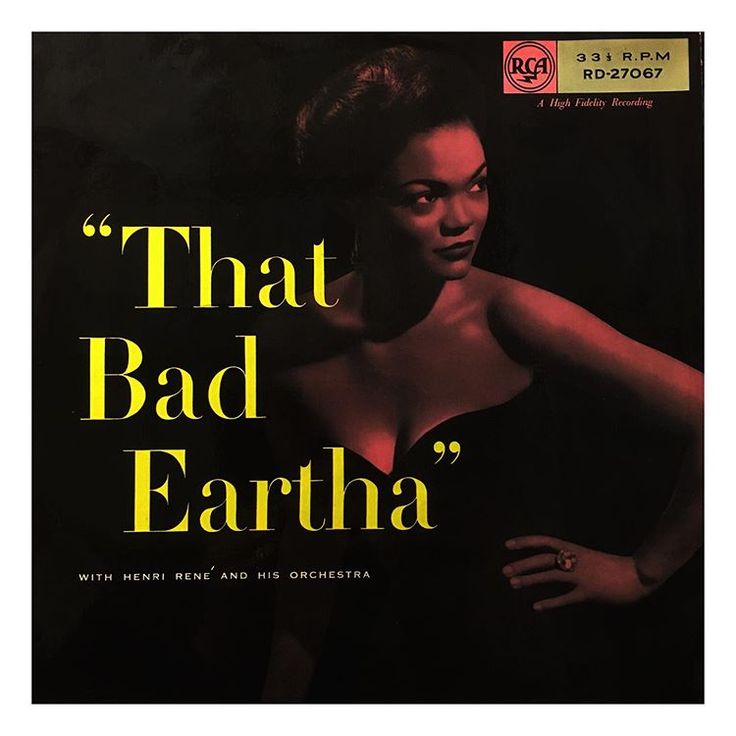

After Le Perroquet, Kitt’s next night-club engagement was at the cosmopolitan Karavansari in Istanbul. There she learned a number of Turkish songs by ear, including Usku Dara, which she later recorded as her first single for RCA Victor. By the time she opened at La Vie En Rose in New York, she claimed to sing in seven languages.

Despite an inventive campaign of newspaper ads, which read “Learn to say ‘Eartha Kitt’ “, she was not a success, and her two-week contract was terminated after six days.

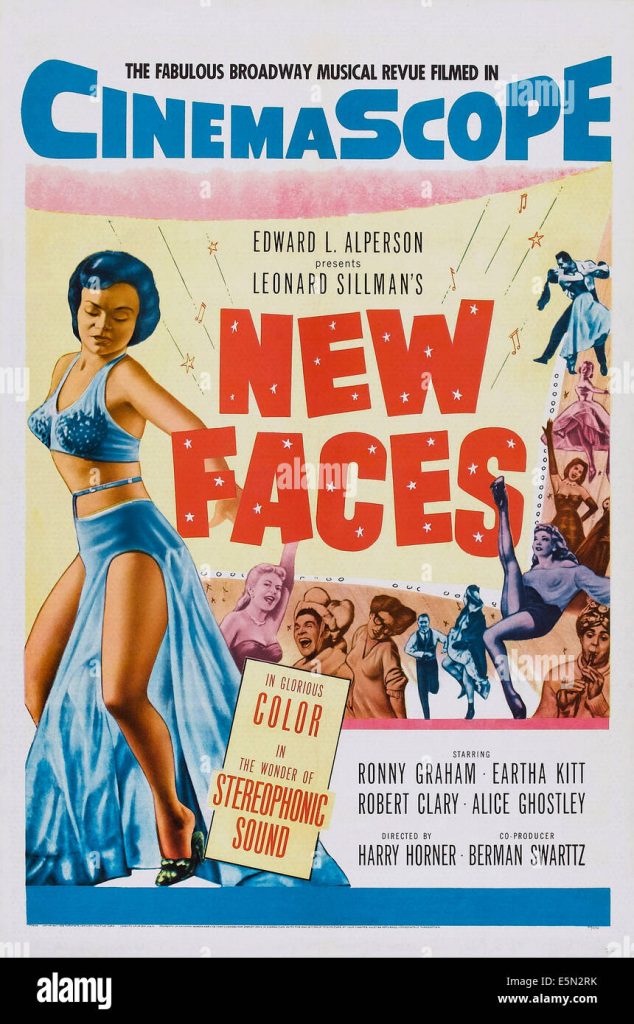

Whatever went wrong, La Vie En Rose’s loss was the Village Vanguard’s gain, and a short engagement at its sister club, The Blue Angel, was extended to 25 weeks. She was spotted by the producer of a long-established revue. For New Faces of 1952, she sang Monotonous while crawling catlike from one chaise-longue to the next. Thereafter, Kitt found it hard to do without at least one such piece of furniture, and for a Royal Variety Performance in the 1960s, she appeared on it through the stage trapdoor.

Kitt became the unquestioned star of New Faces and a film version followed in 1954. Meanwhile, she starred in Mrs Patterson, her first major Broadway success, and fell in love with Arthur Loew Junior, heir to a chain of cinemas. Feelings were mutual, but the affair never came to anything because his mother opposed it. In London, Kitt had appeared briefly at Churchill’s in the early 1950s, but she really arrived with her act at the Café de Paris, wearing an aquamarine silk satin dress designed by Pierre Balmain. Lord Snowdon photographed her.

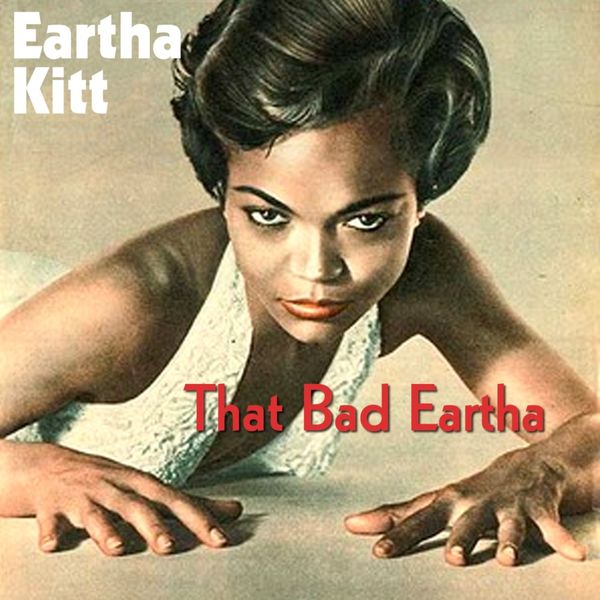

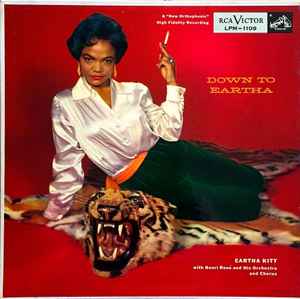

The 1950s were the golden decade of Kitt’s record hits. After Usku Dara came Monotonous, I Want To Be Evil and Santa Baby, among others, which established the image of a teasing, self-mocking “sex kitten”. She recorded Just An Old-Fashioned Girl, the song that became her signature tune in Britain, in 1955, but Thursday’s Child and The Day That The Circus Left Town, recorded a short while later, said more about her as the wistful waif people thought weird.

There have been many attempts to describe her extraordinary voice. Kenneth Tynan got it wrong when he spoke of her vibrato, for she hardly used it. Although she cultivated a tremor for special effect, her pitch was remarkably clean, and she would bend it, very often sharp, with slow deliberation. She said she understood everything her voice could and couldn’t do. She played off a gritty chest register against a cooing falsetto, and as she savoured its sound, she would experiment with verbal distortions. Welles complained that she seemed to come from nowhere.

Kitt’s very distinctive style made it hard for her to develop her career and diversify. If she was not 100% herself, you felt cheated. Yet she never stopped trying.

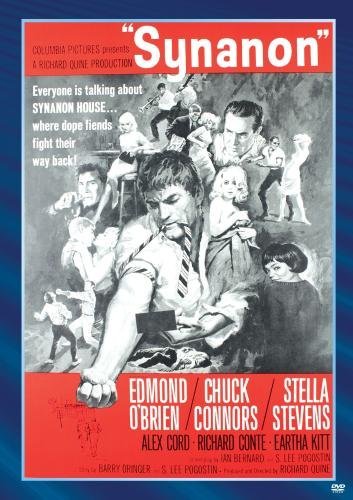

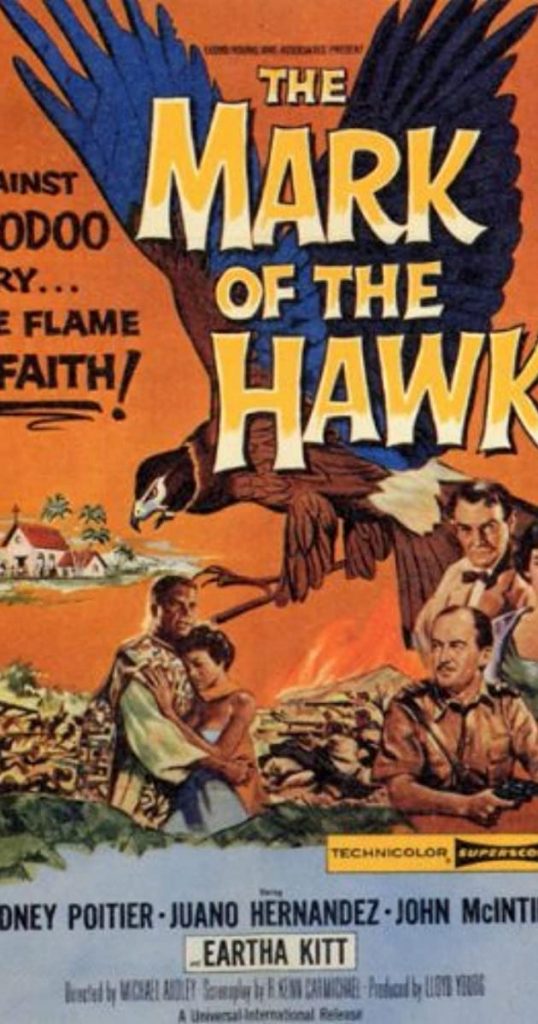

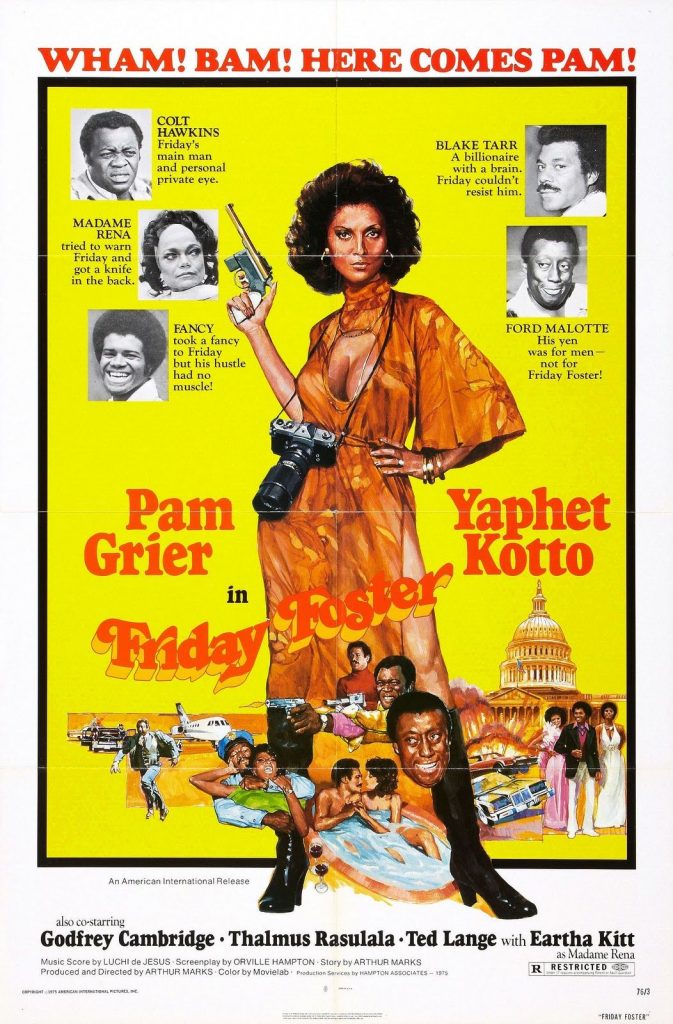

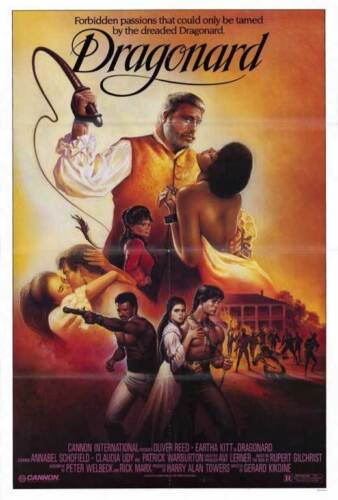

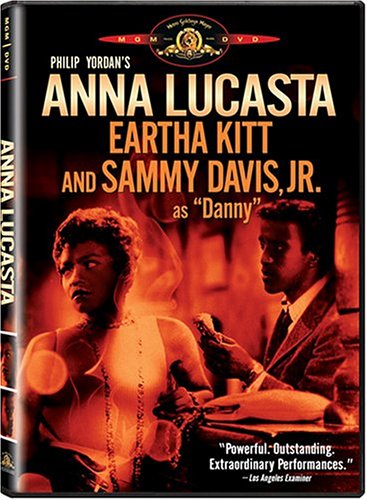

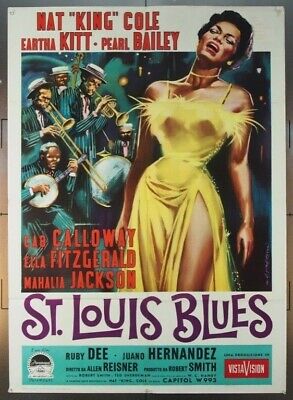

Her films included St Louis Blues (with Nat King Cole) and Accused (1957), Anna Lucasta (with Sammy Davis Jr) and Mark Of The Hawk (1958), Saint Of Devil’s Island (1961), Synanon (1965) and Dragonard (with Oliver Reed, 1971).

Apart from many celebrity appearances on TV, she found one role tailormade as Catwoman in Batman (1967-68). She took further parts on Broadway, in Shinbone Alley (1957) and Timbuktu (1978), an all-black musical based on Kismet. In London she played Mrs Gracedew in Henry James’s The High Bid (1970) and the title role in Bunny (1972).

In 1988 her appearance in Sondheim’s Follies at London’s Shaftesbury theatre — she spent most of it elegantly posed in a long mink coat until she stopped the show with I’m Still Here — led the following year to her first one-woman show, Eartha Kitt in Concert. Prancing around with three toy boys, she was pretty well as lissome as ever, and even more over the top. In Manchester, she even tried panto, as the Genie of the Lamp in Aladdin.

Also in 1989 came her autobiography, I’m Still Here: Confessions of a Sex Kitten. It retells and updates her earlier memoirs, the first volume of which, Thursday’s Child, was published in 1957. I’m Still Here ends with Kitt’s struggle to come to terms with the marriage of her only daughter, Kitt, of whom she was fiercely possessive.

Her own marriage to Kitt’s father, Bill McDonald, in 1960 soon fizzled out. Kitt made no bones about the fact that the thing she needed most, after the love of her daughter, was the applause of an audience: I once saw her give everything she’d got to what was virtually an empty house, at the New Theatre, Oxford, one weekday matinee.

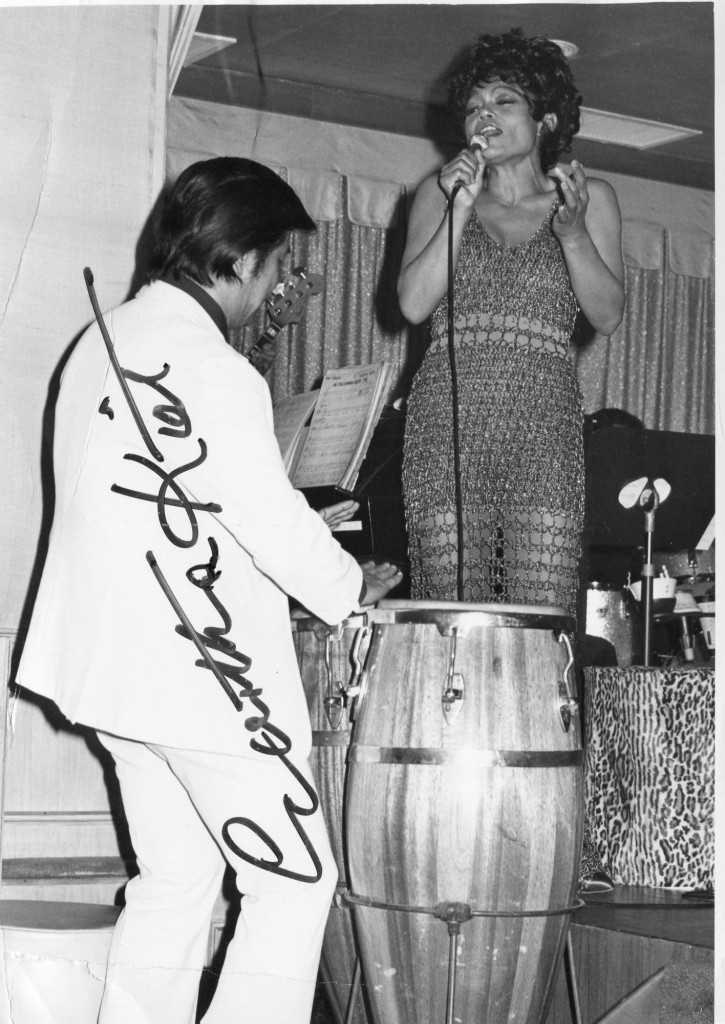

She looked like almost losing her American public after she upset Lady Bird Johnson by speaking her mind about the Vietnam war at a 1968 luncheon at the White House. The CIA described her as “a sadistic nymphomaniac”. America’s temporary loss was Britain’s gain, for Kitt spent more time here, touring variety clubs in the north of England.

At the opposite cultural extreme, she made two extraordinary concert appearances in London with Richard Rodney Bennett, as pianist and arranger, and the Nash Ensemble, singing songs by Kurt Weill, Cole Porter and other American standards.

Kitt’s occasional attempts to move with the times — she even dipped into disco funk — had qualified success. In 1984 she was back in the charts with Where Is My Man and I Love Men. She did not need to update herself, and a live recording of a concert she gave with jazz musicians in Wuppertal, Germany, in 1992 shows that she was best given a tight format – never better than in the immaculate arrangements of Henri René and his Orchestra in the early days. An album called I’m Still Here came out the same year as the book, and in 1993 Rollercoaster issued a five-disc compilation representing her entire repertoire to date.

Her work continued, notably in cabaret: in 2000 she provided the voice of Yzma for the Disney animation The Emperor’s New Groove; her appearance at the Cheltenham jazz festival last April saw her in yet another medium, the live performance on DVD; and she continued to perform until last October.

Her album Back in Business (1995) had made a bid for the universal by dressing up old favourites by Cole Porter, Rogers and Hart, Duke Ellington, and Kurt Weill, not to mention Henry Mancini’s Moon River, in highly produced, sumptuous jazz arrangements. One of the more straightforward is the classic of the 1930s depression, Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?, and here Kitt rings true with raw anger.

Eartha Mae Kitt (Keith), singer and entertainer, born 17 January 1927; died 25 December 2008

The above obituary can also be accessed online here.