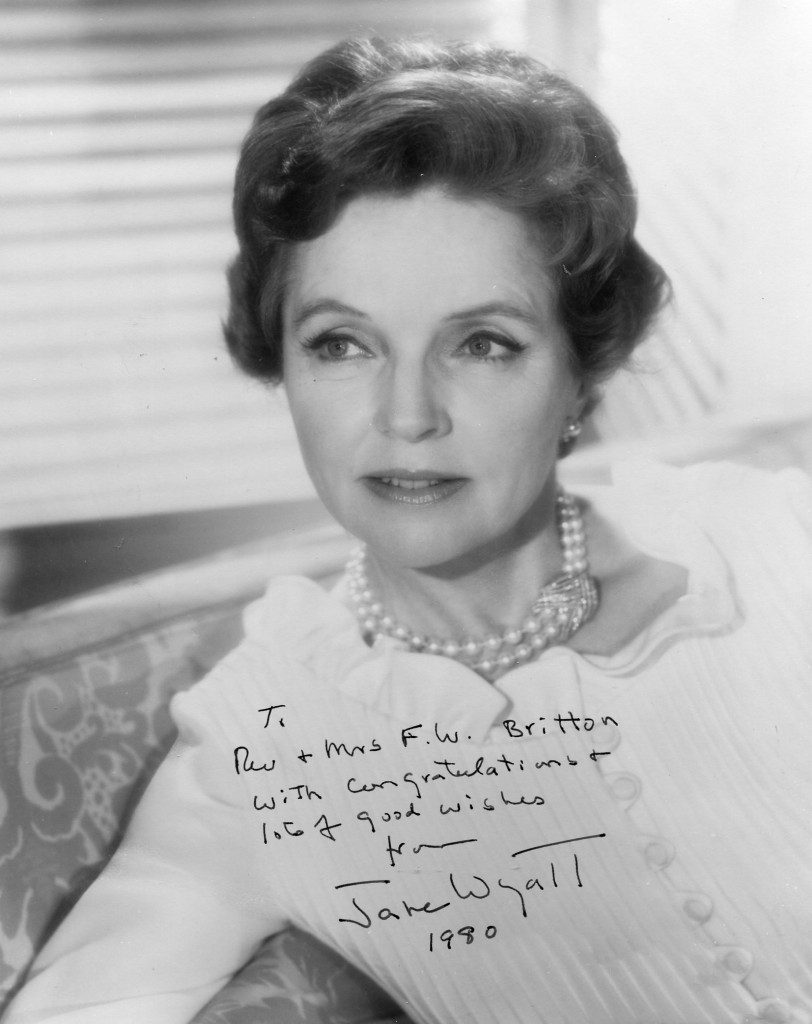

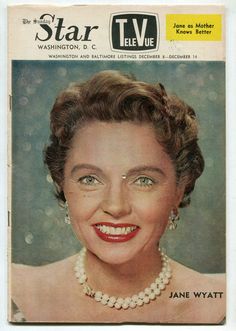

Jane Wyatt obituary in “The Independent” in 2006.

Jane Wyatt was a warm loving presence in many films and television roles from the early 1930’s. She was born in 1910 in New Jersey. In 1937 she made her most famous role in “Lost Horizon” opposite Ronald Colman. Her other films include “None but the Lonely Heart” with Cary Grant”, “Gentleman’s Agreement” with Dorothy McGuire whom she physically resembled and “Boomarang”. On television she played Robert Young’s wife in the very long running “Father Knows Best” and Norman Lloyd’s wife in “St Elsewhere”. Jane Wyatt died in 2006 at the age of 96.

Tom Vallance’s obituary of Jane Wyatt in “The Independent”:

Jane Wyatt had an exceptionally long acting career in film, television and on stage. Petite and pretty, she had an innate warmth that permeated her performances in such films as Lost Horizon and Pitfall, and brought her many roles as congenial, understanding wives – an image she had great success with on television in the series Father Knows Best, for which she won three Emmy Awards. Later a new generation discovered her as Spock’s mother in Star Trek.

She was also a leading figure in Hollywood society, as befitting a descendant of early Dutch settlers – a paternal ancestor, Philip Livingston, was a signatory of the Declaration of Independence.

Wyatt’s mother was a Colonial Dame of America, her father of English and Irish stock. When Jane Waddington Wyatt was born in Campgaw, New Jersey, in 1910, they were part of New York’s famed “Four Hundred” but, contrary to some reports, they did not threaten to disown their daughter when she declared her ambition go on the stage. “I can’t remember a time when I didn’t want to be an actress,” she recalled:

I’ve read reports that my family didn’t want me to act and disowned me. Not a bit of it. My mother was a dramatic critic for 35 years. I was surrounded by drama. All my father’s side of the family were Episcopalian ministers, and he said, “What’s the difference between the pulpit and the stage?”

Attending Barnard College, part of Columbia University, Wyatt performed in school plays and during the summer acted with the Berkshire Playhouse:

They asked me to come back the next summer, so I thought, “I’m not going back to college. I’m going to get a job and learn how to act.” So I walked up and down Broadway trying to get a job. It was fun, but I don’t know if you can do that today.

She made her Broadway début as the ingénue in Give Me Yesterday (1931) by A.A. Milne, playing the daughter of the English prime minister (Louis Calhern). Other small roles followed, while she studied with Miss Robinson Duff, whose other pupils included Katharine Hepburn and Ina Claire. Plays in which she appeared on Broadway included Fatal Alibi (1932), starring Charles Laughton and based on Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Somerset Maugham’s For Services Rendered (1933), and Evensong (1933), in which she played the niece of a temperamental opera star (Edith Evans):

Evans had had a big hit with the play in London, and I remember the director telling us that this was one of the greatest actresses in the world, but somehow on the opening night she was awfully nervous and she did not get good reviews. I got spectacular reviews.

Offered a Hollywood contract that allowed her to take stage work in New York, she made her screen début as the younger sister of Diana Wynyard in James Whale’s One More River (1934 – “I adored Diana,” she said), and then played Estella in Great Expectations (1934), co-starring Phillips Holmes as Pip. “He was beautiful-looking and just as nice as could be,” recalled Wyatt, “but he was on drugs. He was the first person I had heard of being on drugs – it was to ruin his career.”

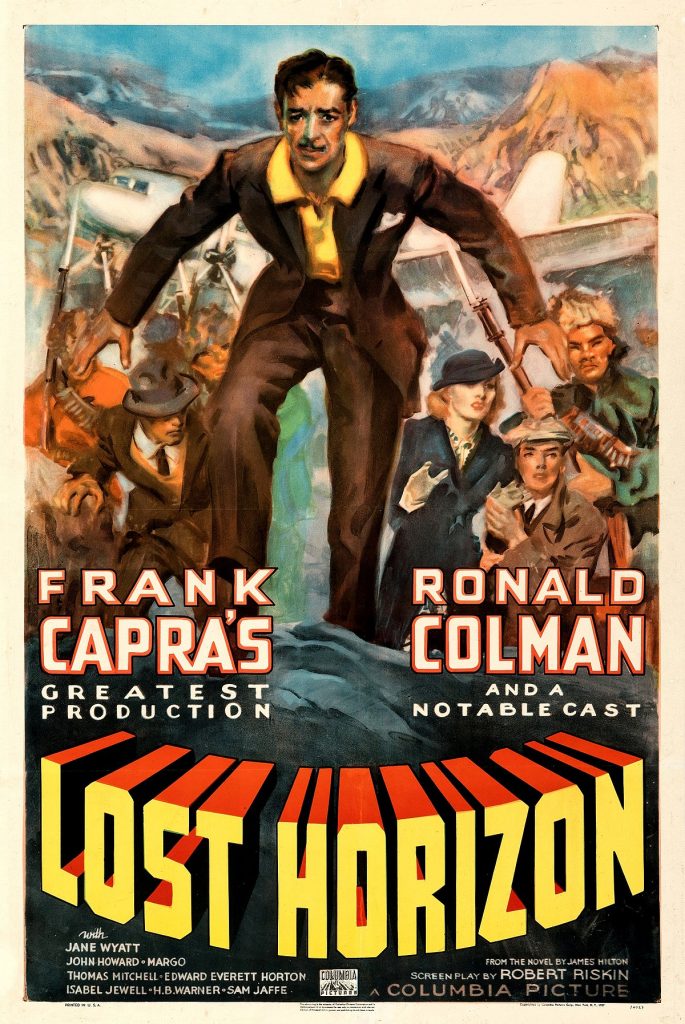

After roles in We’re Only Human and The Luckiest Girl in the World (both 1936), Wyatt was cast in her most memorable role, in Frank Capra’s enduring fantasy Lost Horizon (1937), which put the word Shangri-La (the dream city in which people hardly age) into the English language:

Frank said he needed an unknown, but somebody experienced in movie-making, and since I’d only done flops I fit the bill . . .

Lost Horizon was “a hit but not a smash”. She attributed much of the film’s appeal to its cast:

Those great character actors are gone. In 1937 we’d see them in every other picture so they seemed less special. Now we can sit back and appreciate them because that kind of acting will never be seen again.

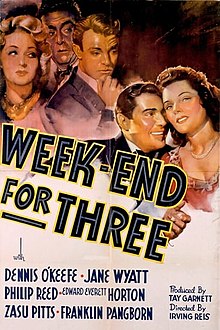

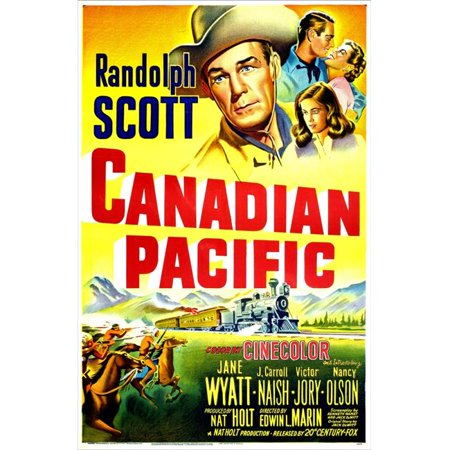

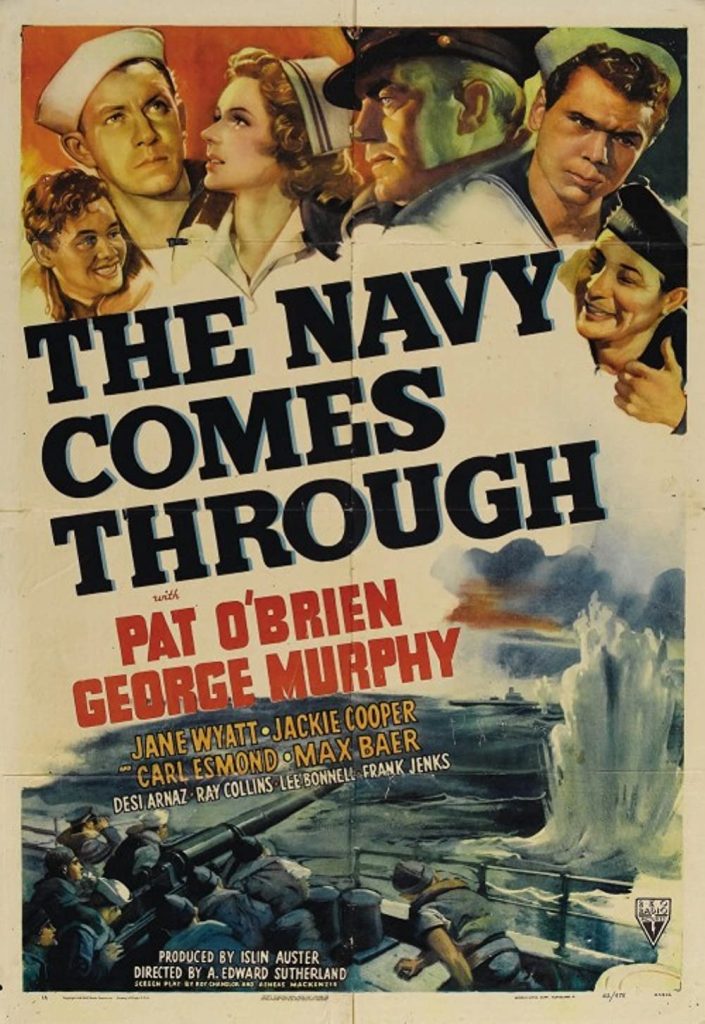

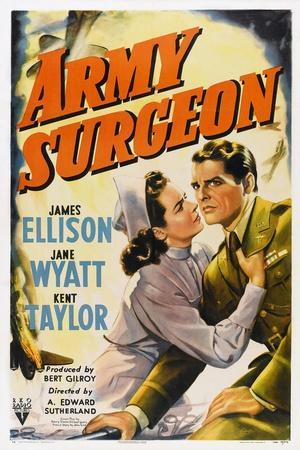

Her next films were inconsequential, and in 1940 she returned to Broadway to star alongside Elia Kazan and Morris Carnovsky in Clifford Odets’s Night Music, a Group Theatre production that ran for only 20 performances, though the three leading players received glowing reviews. She returned to Hollywood to appear in wartime morale boosters such as Army Surgeon and The Navy Comes Through (both 1942) and the westerns Buckskin Frontier and The Kansan (both 1943):

They were fun because I loved to ride. My leading man in both was Richard Dix from the silent days, and he was old enough to be my father. By the time he’d put on his hat and his dentures in and he had his corset on and high heels, he was more romantic than anyone in the picture.

None but the Lonely Heart (1944), written by Odets, starred Cary Grant in the offbeat role of a cockney down-and-out:

A lot of the Group Theatre were in that. Cary, who told me this was as close as he ever got to revealing his true self to audiences, should have won an Oscar, but people didn’t like him in that sort of role.

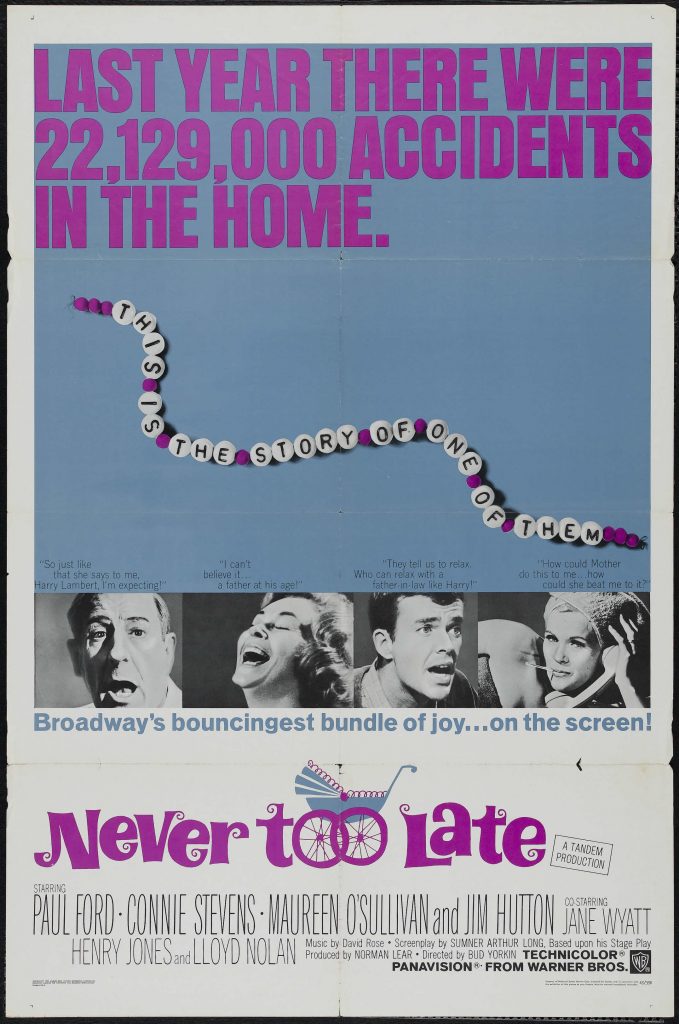

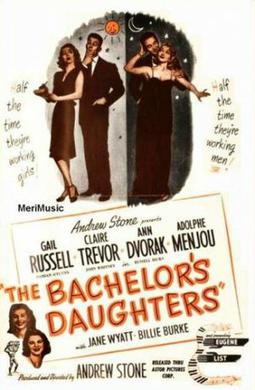

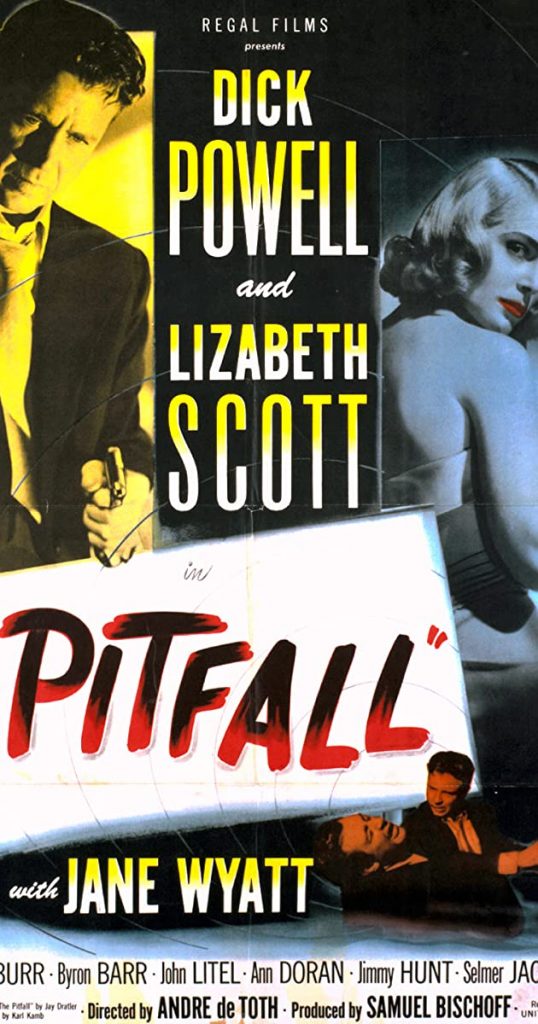

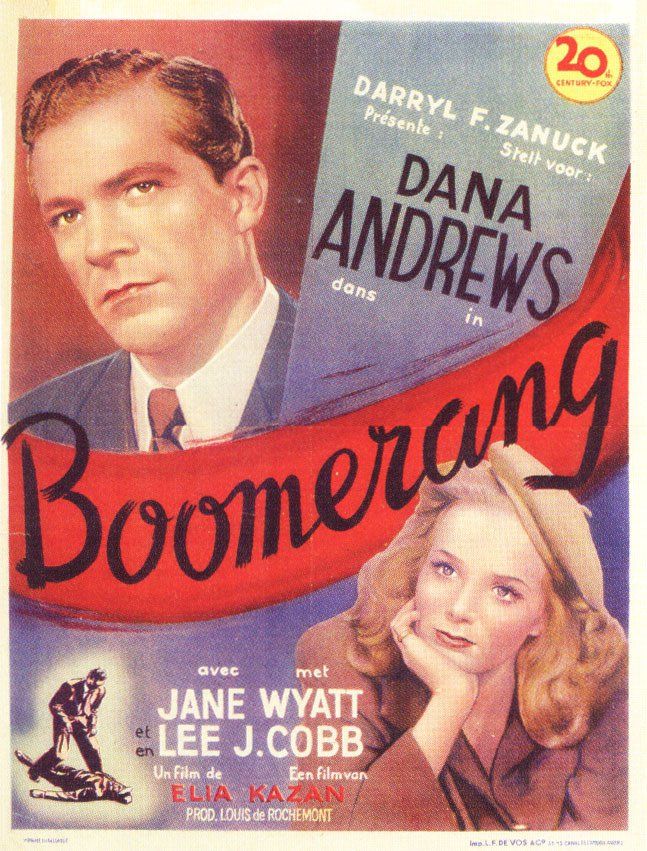

After a Broadway hit, Hope for the Best (1945), and a tour as Sabina in The Skin of Our Teeth (1946), Wyatt co-starred with Adolph Menjou and Gail Russell in the amusing film comedy The Bachelor’s Daughters (1946), then played a small role in the Oscar-winning film about anti-Semitism, Gentleman’s Agreement (1947), directed by her friend Elia Kazan. She then appeared in another distinguished Kazan film, Boomerang! (1947), as the wife of an an attorney (Dana Andrews), and followed this with one of the finest of her “wife” roles, that of the wife and mother whose husband (Dick Powell) has an affair in André de Toth’s highly regarded film noir Pitfall (1948). The French critic Philippe Garnier wrote of the moment when Wyatt discovers the affair,

It is on Jane Wyatt’s haggard face that one’s attention finally rests. This pretty little face, usually so strong and witty, is suddenly broken by pain, humiliation and incomprehension. And this is the same face found in the last scene, eyes fixed on the car windscreen in order not to look at her husband while, in a feeble voice, she announces the sort of pardon which has nothing to do with a happy ending . . . One of the most chilling endings in the history of cinema. And also one of the most realistic.

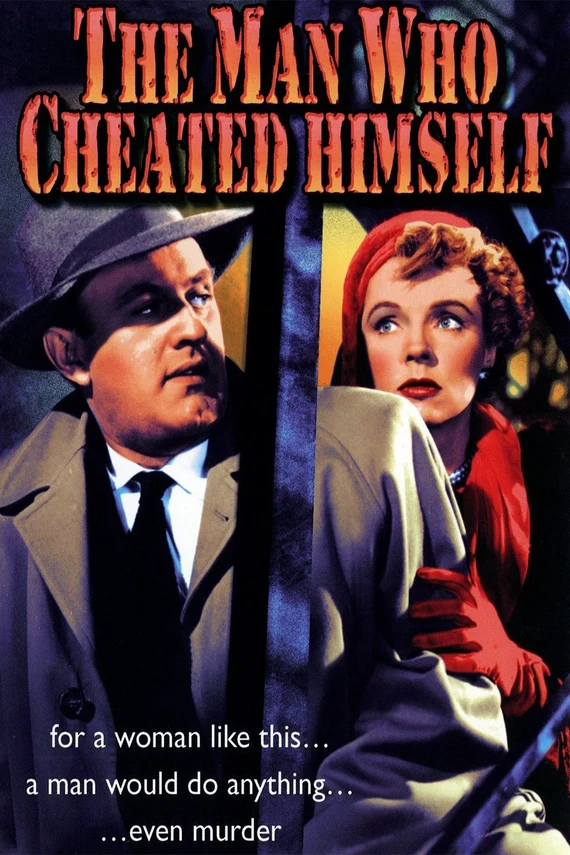

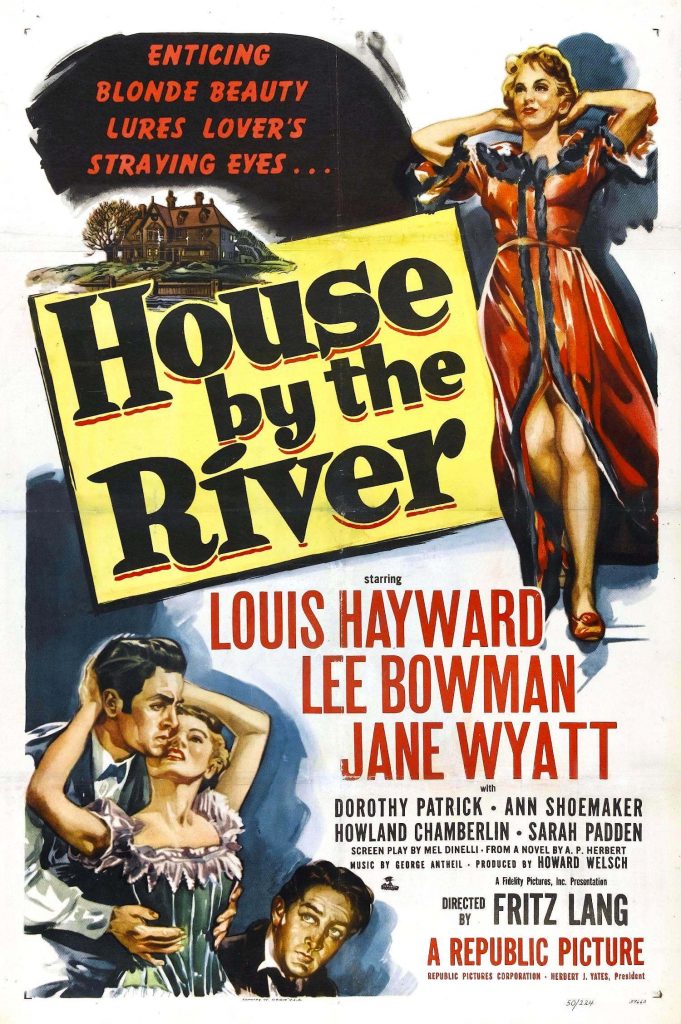

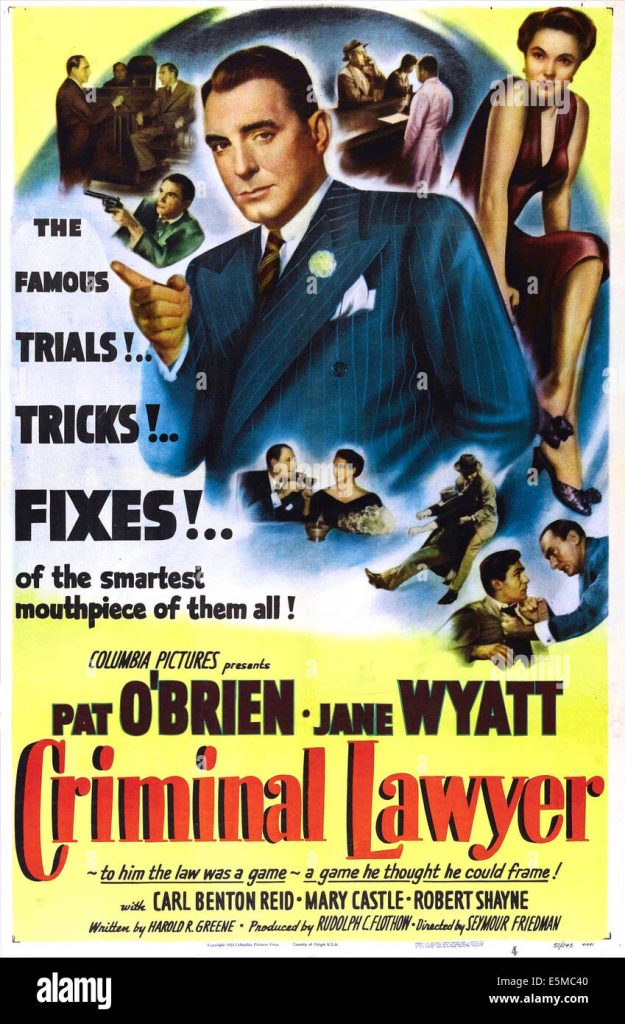

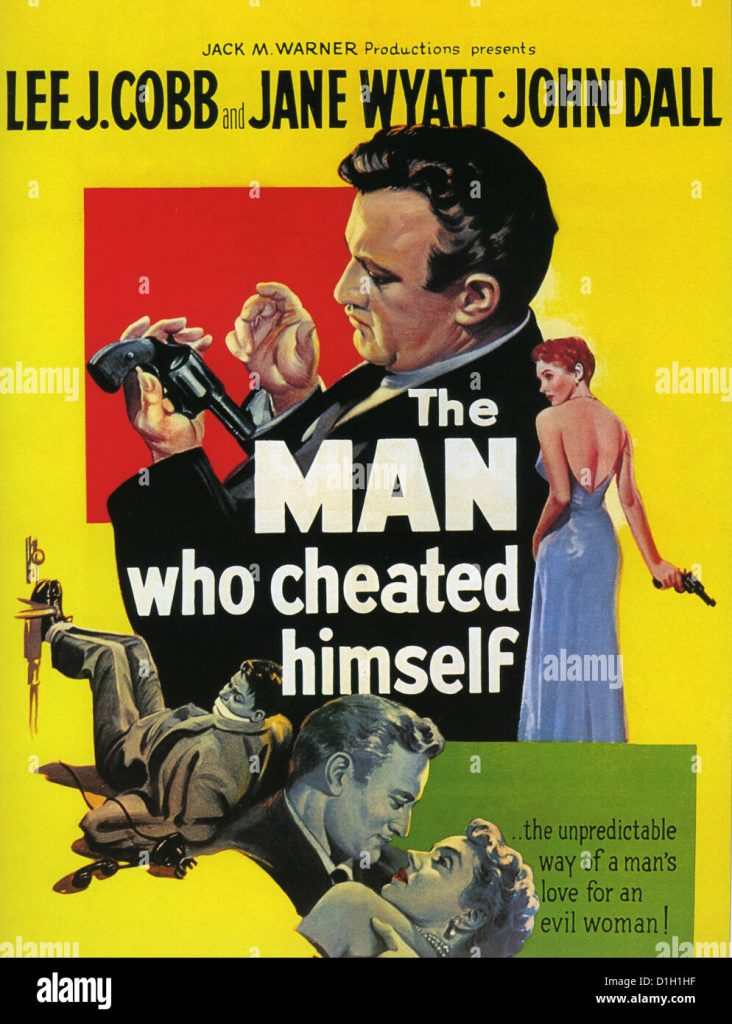

Wyatt next played Gary Cooper’s wife in the 1949 naval drama Task Force (“Cooper, who had casting approval, jokingly told me he asked for Jane Wyman and got me by mistake”) and a wife and mother distressed at her eldest daughter’s reaction upon discovering she was adopted in Our Very Own (1950), then returned to film noir with Fritz Lang’s The House by the River (1950). She starred with Lee J. Cobb in The Man Who Cheated Himself (1951), but too many of her roles were inconsequential – such as Betty Grable’s best friend in My Blue Heaven (1951) – and movie offers became scarce after she joined a group of stars who flew to Washington to protest at the hearings of the Un-American Activities Committee.

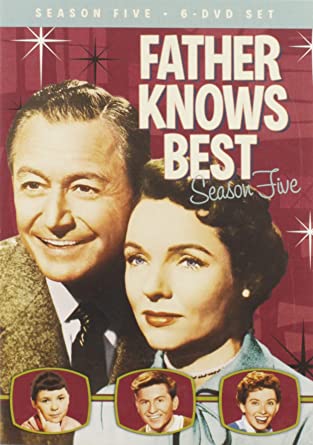

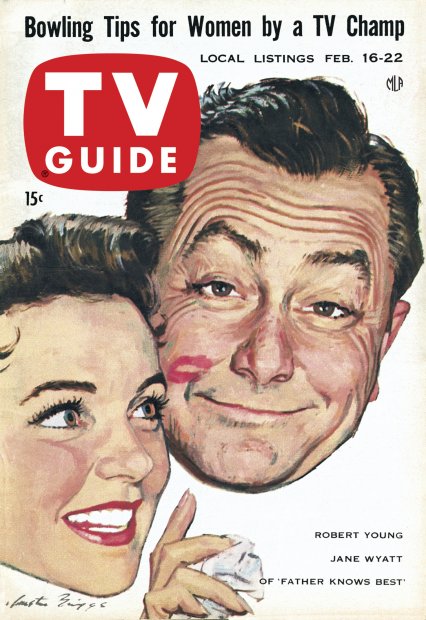

Film offers already made were rescinded, and further offers were unforthcoming. “So I went to New York and did live television, which I loved doing.” Wyatt returned to Hollywood when asked to appear in the television version of a radio show, Father Knows Best:

I was asked time and again and said, “No.” I didn’t want to be in a TV series. To me it seemed so way down below you and so boring to be stuck in a part. My agent called and said it was the last chance, and my husband said, “Look, you’ve been in New York all this time and haven’t had a decent play. Why don’t you read the script?” Well, I read it and it was charming, so I agreed, returned to Hollywood, and did it for six years [1958-63], and it was fun. It could have gone on forever, but the children had grown up.

Each show started with the husband (Robert Young) arriving home from work, taking off his sports jacket and putting on a comfortable sweater before dealing with the everyday problems of a growing family. He and his wife Margaret (Wyatt) were portrayed as thoughtful, responsible adults (in contrast to the majority of situation comedies of the time) and when the series ended it was at the peak of its popularity. Wyatt won Best Actress Emmy awards for her role in 1958, 1959 and 1960.

A later television role was to bring Wyatt notoriety, that of Spock’s earth-born mother in the Star Trek episode “Journey to Babel” (1967), a role she reprised in the film Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986):

I get fan mail from Father Knows Best and Lost Horizon, but the Star Trek mail gets more and more. I’m a human who married a Vulcan – someone has written a whole book about the mother.

Wyatt once said, “My dream of being in a great Broadway play never did come true.” Asked by Michael Gartside in 1998 what her philosophy was, she replied,

To have a happy marriage. I have been married for 63 wonderful years, and I adore my sons. But it is hard to act and be a family person.

Her husband, Edgar Ward, died the day before their 65th wedding anniversary. She said, “The acting was the icing on the cake, really.”

Tom Vallance

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.