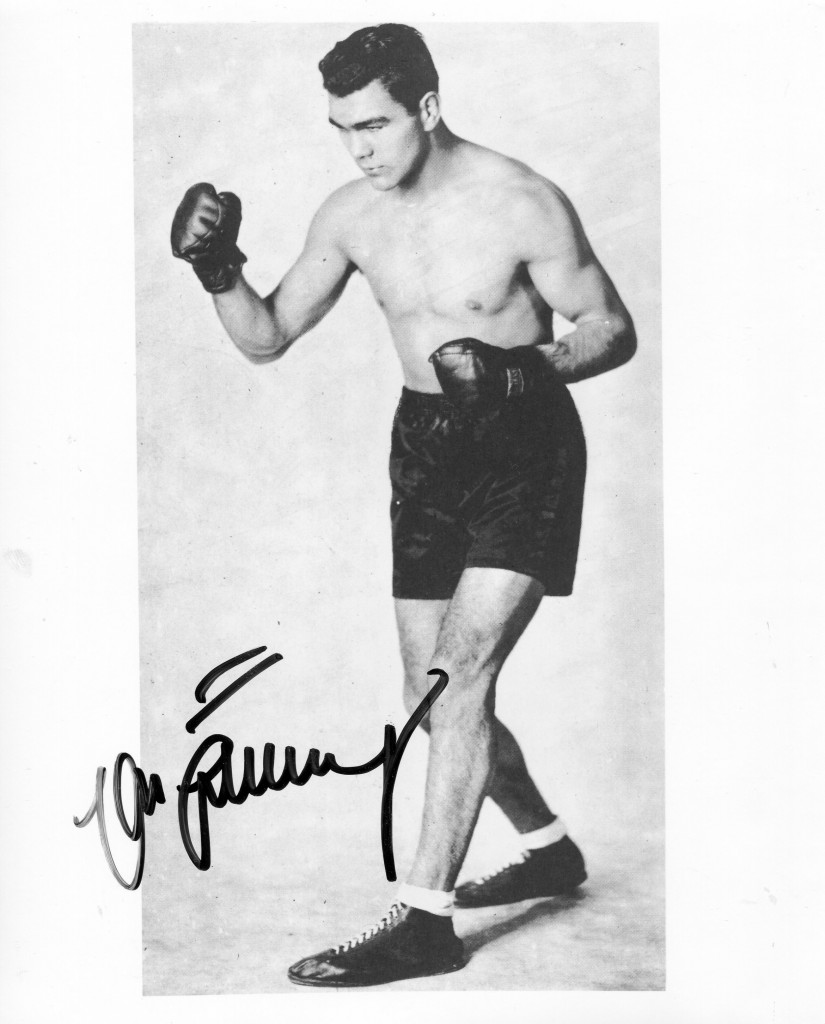

The great boxer Max Schmeling was born in 1905 in Brandenburg, Germany. He was World Heavyweight Champion from 1930 to 1932. He was married to actress Anna Ondra. He was featured in the films “Liebe in Ring” in 1930 and “Knockout” in 1935. After retiring from the ring, he became a very wealthy businessman and died in his 100th year in 2005.

His “Guardian” obituary by Mike Lewis:

Max Schmeling, Germany’s former world heavyweight champion, who has died aged 99, will primarily be remembered as the boxer who lost the most politically charged sporting bout in history. That was his crushing, one-round defeat by the American Joe Louis, the “Brown Bomber”, at New York’s Yankee Stadium on June 22, 1938.

From the opening bell, Louis, the champion, tore into Schmeling and sent him staggering around the ring under a merciless assault. Schmeling, dropped three times, was bewildered, semi-conscious and slumped on all fours when rescued by the referee, after one of the most savage onslaughts ever seen in a prize ring. The victory of Louis, after two minutes and four seconds, was his most awesome performance.

It was the approach of the second world war that transformed the nature of the fight and made Schmeling an unwilling propaganda tool of the Nazis. The confrontation was sold as a fight between a member of Hitler’s “master race” and an American black, and assumed huge symbolic importance.

There were calls to “boycott Nazi Schmeling” and he protested in vain that this was “just another fight”. While, despite Louis’s assertion that he was fighting for “the good old USA”, white reporters from southern states – where Jim Crow white supremacist racialseg regation ruled – openly hankered for a German victory. Even as Schmeling, nicknamed “Hitler’s show-horse”, had tea with the Führer on his way to the title challenge bout, German troops massed on the borders of Czechoslovakia.

The drama began on June 19, 1936, when Schmeling caused the “sensation of the century” by knocking out Louis in the 12th round of a non-title bout. That defeat for Louis – his first in 28 fights – caused riots in Harlem. A man who had backed Schmeling was stabbed and had his skull fractured.

Schmeling’s success happened two months before the Nazi attempt to use the Berlin Olympics as a showcase for white, Aryan supremacy (ruined by the triumph of black American athlete Jesse Owens).

Schmeling’s future would have been different had he lost that first encounter with Louis. During the build-up, friendly US sportswriters described the German as gentlemanly, sportsmanlike and courageous. Their attitude changed dramatically when Schmeling, a huge underdog, flattened the unbeaten Louis with a straight right.

The fight was almost ignored by the Nazi press, after Hitler privately questioned the wisdom of taking on the invincible American; but Schmeling’s shock victory led to wild celebrations in Germany. He received congratulatory cables from the propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels; and also from Marlene Dietrich, by then in American exile.

A film of the fight played to packed houses in Germany. A Nazi weekly journal, Das Schwarz Korps, commented: “Schmeling’s victory was not only sport. It was a question of prestige for our race.”

The irony was that Schmeling, who had been world heavyweight champion from 1930-32, did not support Hitler’s racial and religious persecutions. In 1935, he had blatantly defied the Führer’s order to replace Joe Jacobs, his Jewish-American trainer. He also refused to divorce his Czechoslovakian film star wife, Anny Ondra. On November 9, 1938, five months after his defeat by Louis, he sheltered two Jewish boys in his Berlin apartment during Kristalnacht, when the Nazis instigated public violence against Germany’s Jews.

Born in Uckermark, in the state of Brandenburg, Schmeling was raised in Hamburg and had ambitions to be a football goalkeeper until, at the age of 14, he saw a newsreel of the US boxer Jack Dempsey. Schmeling, self-taught, developed sound skills, an iron physique and a powerful punch with either hand. He turned professional in August 1924, winning the Germany light-heavyweight title three years later and the European crown in 1928.

In pre-Nazi Berlin, one of the most glamorous, exciting cities in Europe, Schmeling was as feted by high society as was Dietrich at the height of her Blue Angel movie success. “It was a time that wanted heroes,” he remembered.

Following two successful European title defences, Schmeling moved up to heavyweight to challenge American Jack Sharkey for the world title, left vacant by the retirement of Gene Tunney. The fight was in New York on June 12, 1930; Schmeling won on a foul in round four, after a short left hook to the groin left him in agony. It was the first time the world title had been decided in such circumstances.

Schmeling beat Young Stribling on a 15th-round stoppage at Cleveland in 1931, only to lose his title on a split decision to Sharkey at Long Island on June 21, 1932, a controversial verdict that prompted an enraged Jacobs to cry: “We wuz robbed.”

Schmeling paid a high price for his defeat by Louis. He was the only top German sportsman to be drafted into the Wehrmacht. At the outbreak of war, he was called into a parachute regiment, and, in 1941, was wounded in the battle for Crete.

Having lost his property and wealth in the war, Schmeling made a comeback on his 42nd birthday, knocking out Werner Vollmer in round seven. He went on to beat Hans Joachim Dragstein, but was outpointed by Walter Neusel, whom he had stopped in 1934. His last fight was in October 1948; he was outpointed by Richard Vogt. In all, Schmeling had 70 fights, winning 53, including 39 stoppages, drawing four and losing 10. He ploughed his earnings into a farm, acquired business skills and secured a production licence from Coca-Cola.

The longest-lived world heavyweight champion, Schmeling became a successful businessman and a popular, well-respected member of Hamburg society. He avoided interviews, believing that the media had an unhealthy obsession with his distant past. He was probably the last living person to have spoken with Franklin Roosevelt, Hitler, Al Capone, Pope Pius XII – and Marlene Dietrich.

Three decades ago, he said he was almost happy that he had lost the great fight. “Just imagine if I would have come back to Germany with a victory. I had nothing to do with the Nazis, but they would have given me a medal. After the war I might have been considered a war criminal.” He stayed friends with Louis in later years, and even gave him financial help.

He met Anny Ondra on set while he was appearing in a film. They married in 1932, she died in 1987.

· Maximilian Adolph Otto Siegfried Schmeling, boxer, born September 28 1905, died February 2 2005

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.