Paul Scofield obituary in “The Guardian” in 2008.

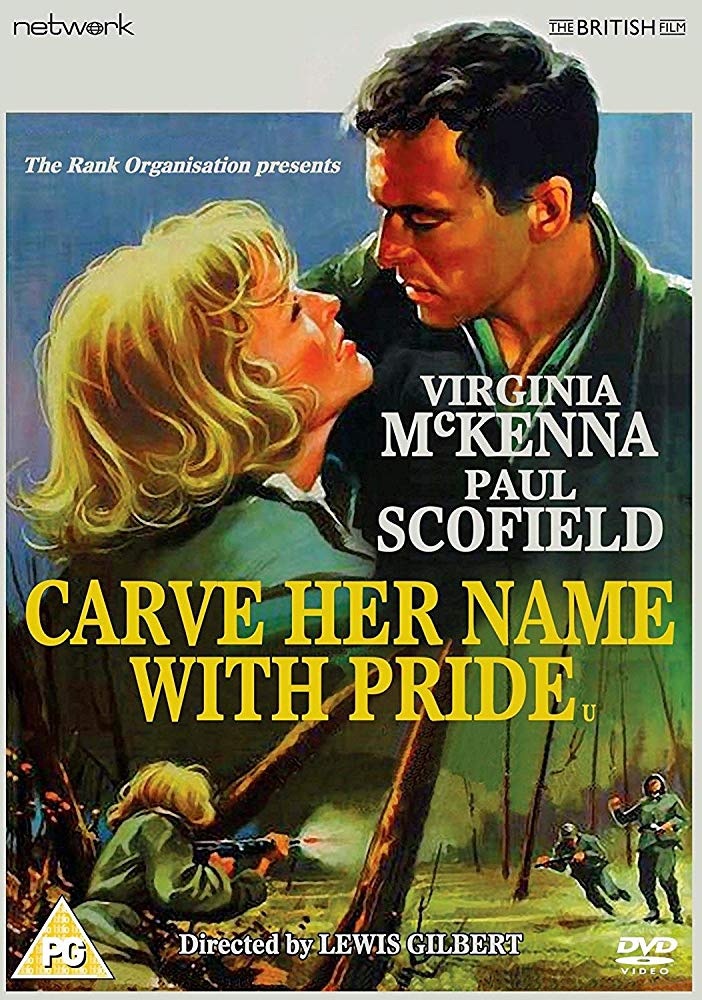

Paul Scofield was born in 1922 in Birmingham. A very gifted actor he had a preference for the stage so that his film performances are few but they are choice. He made his film debut in 1955 in an adaptation of Kate O’Brien’s novel “That Lady” opposite Olivia de Havilland. In 1958 he starred with Virginia McKenna in the very popular film “Carve Her Name with Pride”. In 1966 he won an Oscar for his magnificent performance as St Thomas More in “A Man for All Seasons”. In the United States he made two films “Quiz Show” and “The Crucible” with Daniel Day-Lewis. Paul Scofield died in 2008.

“Guardian” obituary:

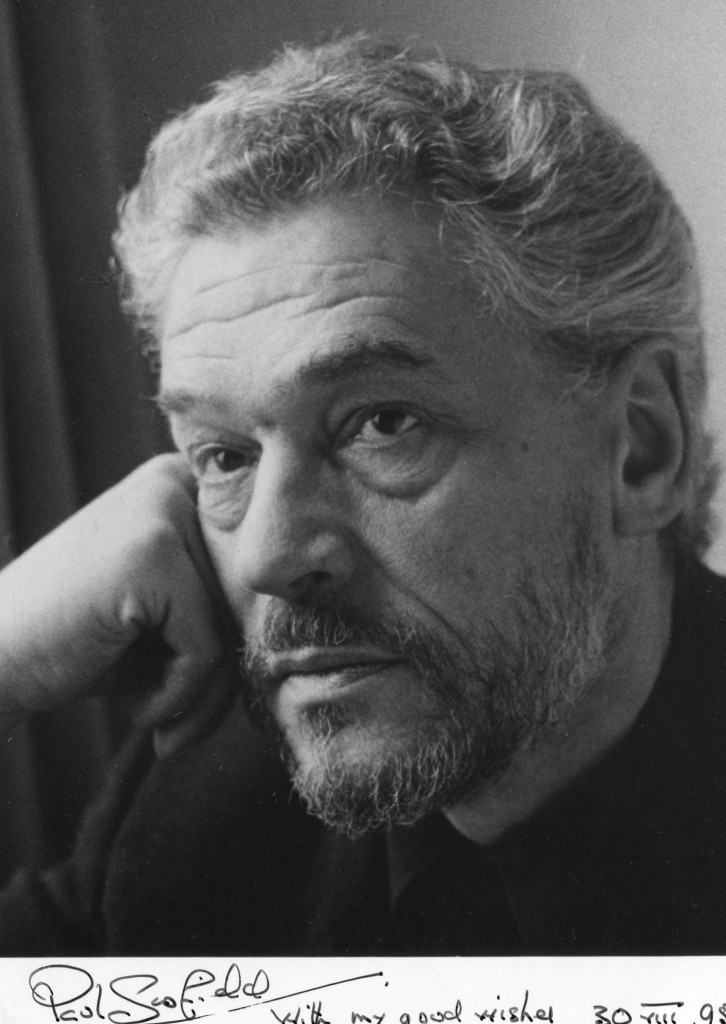

On stage, the actor Paul Scofield, who has died aged 86, was braver than a lion. Off stage this genial man kept his private life quiet as a mouse. This might have made him a frustrating and disappointing subject for interviewers and biographers, but it ensured he was always celebrated for his talent never just as a celebrity. It is almost impossible to think of an actor for whom the term “luvvie” would be more inappropriate.

As Richard Eyre, the former artistic director of the National Theatre, who tempted Scofield back to the theatre to play John Gabriel Borkman at the NT in 1996, observed: “It is hard not to be Pollyannaish about Paul because he is such a manifestly good man, so humane and decent, and curiously void of ego – all the pride he has is channelled through the thing he does brilliantly. He has a very powerful personality, but it is not there as a parallel idiosyncrasy.”

He was born in Sussex to the wife of the headmaster of the Hurstpierpoint village school. He was 13 when he discovered acting at the Vardean school for boys in Brighton, where he was considered an academic no-hoper. He donned a blonde wig for his first role as Juliet in Romeo and Juliet and his natural talent and easy manner on stage won him further starring roles, including Rosalind in As You Like It.

There was never any doubt that he was bound for a career in the theatre and in 1939, aged 17, he left school to begin his training at Croydon repertory theatre. The war intervened, but Scofield was declared unfit for service due to a toe defect that prevented him from wearing military boots. With the Croydon school closed, Scofield moved to the London mask theatre and when two of the teachers, Eileen Thorndike (sister of the famous actor Sybil) and Herbert Scott, decided to evacuate the school to Devon and run it as a repertory theatre, Scofield went with them.

Here he began his training in earnest playing a succession of roles many of which would not have come his way so early but for the war. Although not yet 20, his performances got him noticed. A local critic was impressed, declaring: “One would hesitate to put any limits to what this actor is going to be able to do as he grows older.”

There were indeed no limits, except perhaps those he set on himself in the later part of his career, which meant that there were fewer stage appearances than one might have wished. In an interview Scofield himself once declared: “As an actor I don’t admit to any limitations. In rehearsal one comes up against apparently insuperable barriers, but if one can imaginatively get past them, overreach one’s natural reach, it is astonishing how elastic one can become. I’ve got to go not so far as I can, but as far as is needed. It’s up to somebody else to say if I’ve made a fool of myself.”

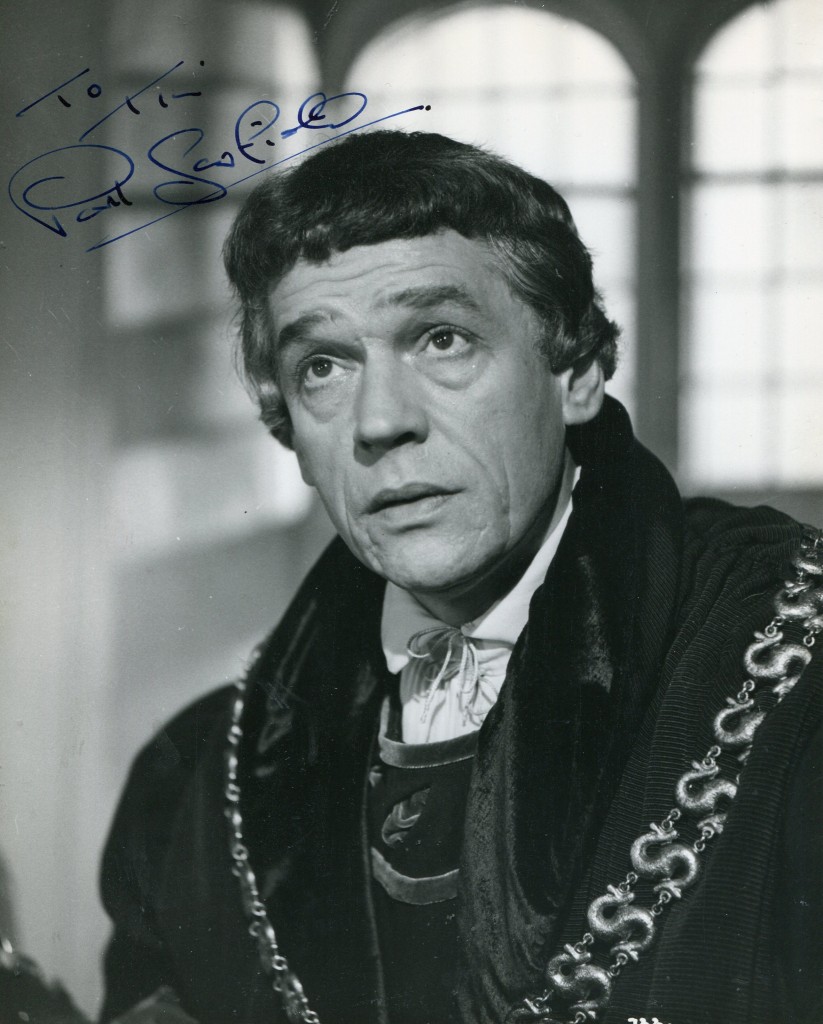

Scofield, more craggily noble in appearance than handsome, always looked more mature than he was (he once said that he had bags under his eyes by the age of 17) and even at this tender age his features had a timeless rather than matinee idol appearance that allowed him to play parts intended for actors much older.

But it was his voice that marked him out. It already had the sonority and “iron sweetness” that the film director Fred Zinnemann, who directed Scofield in his Oscar-winning performance as Thomas More in A Man For All Seasons (1966), called “a Rolls Royce being started up.” The critic JC Trewin once described Scofield’s voice as “sunlight on a broken column”.

This was not to say that a man who became one of the greatest Shakespearean actors of all time always found speaking verse easy. Later in life he was to admit that in his early career he had thought finding the sense of the verse was enough, and that it was only later he realised the crucial importance of rhythm.

Touring the country giving performances in munitions factories and other venues lead to him coming to rest briefly, in 1942, at Birmingham Rep, a theatre that was to play a major part in career. Here he was an exceptional Horatio in Hamlet and also met his future wife, the actor Joy Parker, who was cast as Ophelia. The two married in 1943, and it was his contentment with married and family life that soon followed that gave Scofield the grounding that ensured that he never became too full of himself or saw acting as too glamorous.

Acting, he once opined, was just “my job”. It was through family, not career, that Scofield defined himself. Once when asked how he would like to be remembered, he replied: “If you have a family, that is to be remembered.” After the war he returned to Birmingham Rep, one of the most vibrant theatres in the country under the guidance of the renowned Barry Jackson. Again, a huge number of roles followed quickly from Konstantin in The Seagull to a memorably bombastic Mr Toad in Toad of Toad Hall.

It was at Birmingham that Scofield also met a young 20-year-old director called Peter Brook. who was just starting out on his career. In subsequent years the two men were to be crucial to each other’s futures and reputations. Brook was the first modern director and in Scofield, whose still presence on stage eschewed the flamboyance of an earlier generation, he found the first great modern actor.

As Peter Hall was to observe, Scofield’s talent was “a sulphurous passion” and his acting offered the post-war British theatre “an entirely new note” that set him apart from the Oliviers, Gielguds and Richardsons who came before. Brook’s Hamlet (1955), which became known as the Moscow Hamlet because of its run in the USSR where Scofield was the first English-speaking actor to play the role since 1917, was truly a Hamlet for a generation; although Scofield had already played the role to considerable acclaim in 1948 for director Michael Benthall at Stratford. Harold Hobson declared that he had “never seen a Hamlet more shot through with the pale agony of irresolution.” (In 1990, Scofield came full circle and played the Ghost in Zefferelli’s film of Hamlet, starring Mel Gibson in the title role.)

Scofield had been enticed to Stratford with Jackson and Brook in 1946 and began a long association with the RSC. It was around this time that he also began working in radio, a medium that he adored and which was the perfect vehicle for his beautiful voice. Even in later life when he deserted the theatre for long periods he continued to appear in BBC radio plays and do many readings, attracted by both the quality and the anonymity that the medium offered. It was where he did some of his very greatest work.

Film never had the same appeal for him. Hollywood frequently beckoned from as early as the late 1940s and Darryl Zanuck on seeing a Scofield screen test declared: “That actor! The best I’ve seen since John Barrymore.” In the early years and with a young family, Scofield had no intention of decamping to Los Angeles and by the time he was an established star in the British theatre he had seen what Hollywood had done to some of his contemporaries including Richard Burton, a young actor with a classical talent that Scofield recognised when he admitted that he worried that “he’d get to King Lear before me”.

In the end it was no contest. Scofield first tackled the role aged just 40 at Stratford in 1962 in a Peter Brook production described by Kenneth Tynan as “a mighty philosophical farce” enacted “in a world without gods, with no possibility of hopeful resolution.” Of Scofield’s Lear he declared: “You will never see such another.” The production toured to ecstatic notices around the world, and a film version was made in 1969. Thirty-three years later Scofield returned to the role of Lear in a superb production for Radio Three.

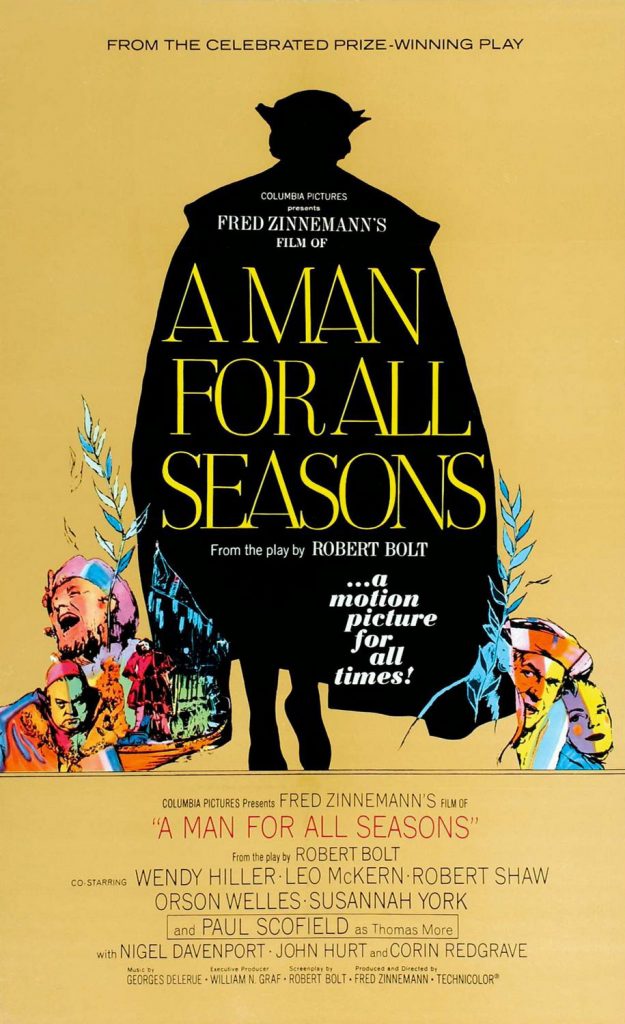

In the end Scofield’s entire work on film amounted to less than 20 roles, and although it was clearly not his natural milieu – he told his biographer Garry O’Connor that he disliked the intrusiveness of the camera – his best performances were magnificent. He deservedly won the Oscar for Sir Thomas More in A Man For All Seasons, a role in which he had already triumphed onstage. He didn’t turn up to collect the Oscar and it was posted to him from Hollywood and got broken in transit which didn’t worry the actor in the slightest.

Twenty years later he got another Oscar nomination for his role as the upstanding Mark Van Doren in Robert Redford’s Quiz Show, a film that brought him to the attention of a younger generation who had never had the opportunity to see him on stage. Two years later he played Judge Danforth in Nicholas Hytner’s screen version of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible and was quite the best thing in it.

The stage, however, was his home for the 1950s to the 1970s, although as that decade progressed his appearances became more infrequent. His choices were always eclectic, ranging from the great classical roles to the musical Expresso Bongo (1958) and even a Jeffrey Archer play Exclusive in 1989.

Away from the classical repertoire his greatest successes were as the whiskey-soaked priest in a stage adaptation of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, a part that he had to dig hard inside himself to find, and which Laurence Olivier, never one to be generous to other actors and potential rivals, declared: “the best performance I can remember seeing.”

Other notable roles were as Alan West in Christopher Hampton’s Savages (1973) and as the envious Salieri, in Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus directed by Peter Hall at the National Theatre in 1979. The latter was a triumph and Scofield could have gone with it to New York. Instead, he chose to stay at the National and play Othello, a role he had already made his own on radio in a 1972 production by John Tydeman who directed much of the actor’s best radio work.

It was from around the time of Othello at the National that Scofield’s stage appearances began to become more infrequent. Although some TV appearances, most particularly the title role in a serial adaptation of Martin Chuzzlewit on BBC TV in 1994, brought him to wid er attention, his stage appearances were few and far between.

When he did appear on stage he dazzled even in old age. In 1992 he played Captain Shotover in Trevor Nunn’s production of Heartbreak House in the West End, and he played John Gabriel Borkman, the dishonoured banker, in Ibsen’s play at the National in 1996. It was, declared the Guardian’s Michael Billington, “his finest performance since King Lear” adding that “Scofield’s greatness lies in the way he reveals the private turmoil behind the posturing facade.”

His final stage appearance was at the Almeida in 2001 when he read the love letters that Anton Chekhov wrote to the actor Olga Knipper, who later became his wife. It was full circle for Scofield who had met the then frail 86-year-old Knipper when he had played Hamlet in Moscow all those years previously.

It was theatre’s loss that Scofield performed so infrequently on stage during the last 30 years of his life, but perhaps he would not have been such a great actor if he had had more of a need to perform. For many actors, it is a flaw in their characters or some damage to their personality that makes them actors in the first place. This was patently not the case with Scofield who did not take his acting home with him and clearly found as much contentment with his family and pottering in his Sussex garden in Balcombe as he did playing the great roles.

This did not demean either, but only added to the sense of an actor whose still quiet centre was not a posture, but the real thing. He was made a CBE in 1956, rejected a knighthood but accepted being made a Companion of Honour in 2001. His greatest honour, however, was in giving a great deal of pleasure to the theatre-going public.

His wife, a son and a daughter survive him.

Brian Baxter writes: With uncharacteristic prescience, Bafta crowned Paul Scofield as best newcomer for his screen debut in That Lady. It was 1955, Scofield was 33 and his role as the elderly King Philip II of Spain had been expanded at the instigation of producer Darryl F Zanuck.

Three years later came Carve Her Name With Pride, playing the colleague who loves Violette Szabo, in a clichéd but decent biopic of the second world war heroine. Despite a preference for theatre, he worked steadily on screen and, excepting Michael Winner’s zoom-laden Scorpio (1973), showed a commitment beyond a desire to pay school fees.

Another war story initiated Scofield into the ways of big budget megalomania. He claimed that he was unsure what movie directors wanted of a classical actor, but John Frankenheimer, who had taken over The Train (1964) from Arthur Penn, saw him as the perfect foil to the athletic Burt Lancaster. Scofield played a fanatical German officer intent on stealing a train load of art treasures; Lancaster a French railway worker out to defeat the Nazi’s plan. It was a logistically ambitious movie and a contrast to Scofield’s next – most famous – film, in which he recreated his triumph as Sir Thomas More. In A Man For All Seasons (1966), his genius was in redefining More in a perfectly nuanced screen performance.

Resisting other offers, he played a cameo in Peter Brook’s anti Vietnam-war movie Tell Me Lies (1968), then took the intriguing role of the thwarted employer in Bartleby (1971). An adaptation of a Herman Melville story about a clerk who proves obstinate and unyielding, it provided a memorable two-hander for Scofield and John McEnery.

For Brook, he reprised his Aldwych theatre success in King Lear (1969). But the movie, shot in Denmark, proved glum and misguidedly busy, redeemed only by Scofield. Scorpio followed it, when, playing a Russian agent, he was reunited with Lancaster. Also in 1973, he co-starred with Katharine Hepburn in Edward Albee’s A Delicate Balance, directed with theatrical reverence by Tony Richardson.

Scofield was off the screen for more than a decade – returning with Summer Lightning (1984). On television he enjoyed greater success, playing Karenin in a sturdy Anna Karenina and Otto Frank in The Attic: The Hiding of Anne Frank (1988).

He was attracted to the ecological drama, When the Whales Came (1989), playing an elderly eccentric, then on familiar ground as the French king in Kenneth Branagh’s rousing Henry V. He stayed with Shakespeare for Franco Zeffirelli’s underrated Hamlet (1990), where Scofield’s mannered and intriguing voice suited The Ghost to perfection.

That spirited work ushered in a busy period, including Utz, from Bruce Chatwin’s novel and the prestige mini-series Martin Chuzzlewit. More interestingly he narrated the first of two docu-dramas by Patrick Keiller. In London (1994), he wryly commented on the state of the capital, as observed by a group exploring the city. Three years later Keiller made Robinson in Space, another jaundiced view of present-day Britain where Scofield’s voice, memorably described as rusty, provided another tellingly oblique commentary.

In contrast, he returned to the mainstream in Robert Redford’s factually based Quiz Show (1994), as the acerbic father to a fraudulent game-show contestant. It gained him an Oscar nomination as best supporting actor. Scofield was memorably cast as Judge Danforth in Nicholas Hytner’s treatment of The Crucible (1996), Arthur Miller’s play about the 17th-century Salem trials. The actor’s slightly imperious manner and timeless face suited period roles. Equally, his distinctive voice added lustre to the TV version of Animal Farm (1999), as Boxer.

· David Paul Scofield, actor, born January 21 1922; died March 19 2008

The above obituary from the “Guardian” can also be accessed online here.