Richard Harris obituary in “The Guardian” in 2002.

The career of Richard Harris has been mile-stoned by a series of noisy headlines – nightclub squabbles, on-set brawls with actors he does not like. It would be tempting to assume that he takes seriously his usual on-screen role as rebel. Oddly, the industry has tolerated his peccadilloes without being compensated with either great reviews or a stampede to the box-office. That Harris was larger-than-life, ‘a character’ was evident, but it was not so immediately obvious on film . In a way he crept up on is in stealth, like the great stars of the 30s, getting better and better, more authoritative, more interesting, more varied”. – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars – The International years”. (1972).

Richard Harris was born in Limerick in 1930. He studied acting at the London Academy of Dramatic Art. He made his film debut in 1958 in “Alive and Kicking” with Kathleen Harrison. He made an impression against stiff acting competition from James Cagney, Don Murray, Glynis Johns and Dana Wynter in “Shake Hands with the Devil” in 1959. He was third billed after Marlon Brando and Trevor Howard in “Munity on the Bounty” and then went on to star in the British sink dra ma “This Sporing Life” as a North of England rugby player. Next he went to Mexico to star with Charlton Heston and Senta Berger in “Major Dundee”. His Hollywood films include “Caprice” with Doris Day and “Camelot”. In 1990 he was nominated for an Oscar for his performance as the Bull McCabe in “The Field”. He was also associated with the Harry Potter movies as Dumbledore. One of his last roles was in “Gladiator”. Richard Harris died in 2002 aged 72.

Ronald Bergan’s “Guardian” obituary:

There was a time when writers could hardly mention the name of the actor Richard Harris, who has died aged 72, without using the dread epithet “hellraiser”. He was lumbered with this reputation for even longer than his drinking buddies and fellow Celts, Richard Burton and Peter O’Toole – with whom had much in common. They all started off on both stage and screen with great promise, but much of their talent was dissipated by appearances in vehicles unworthy of them, with some intermittent flashes of genius.

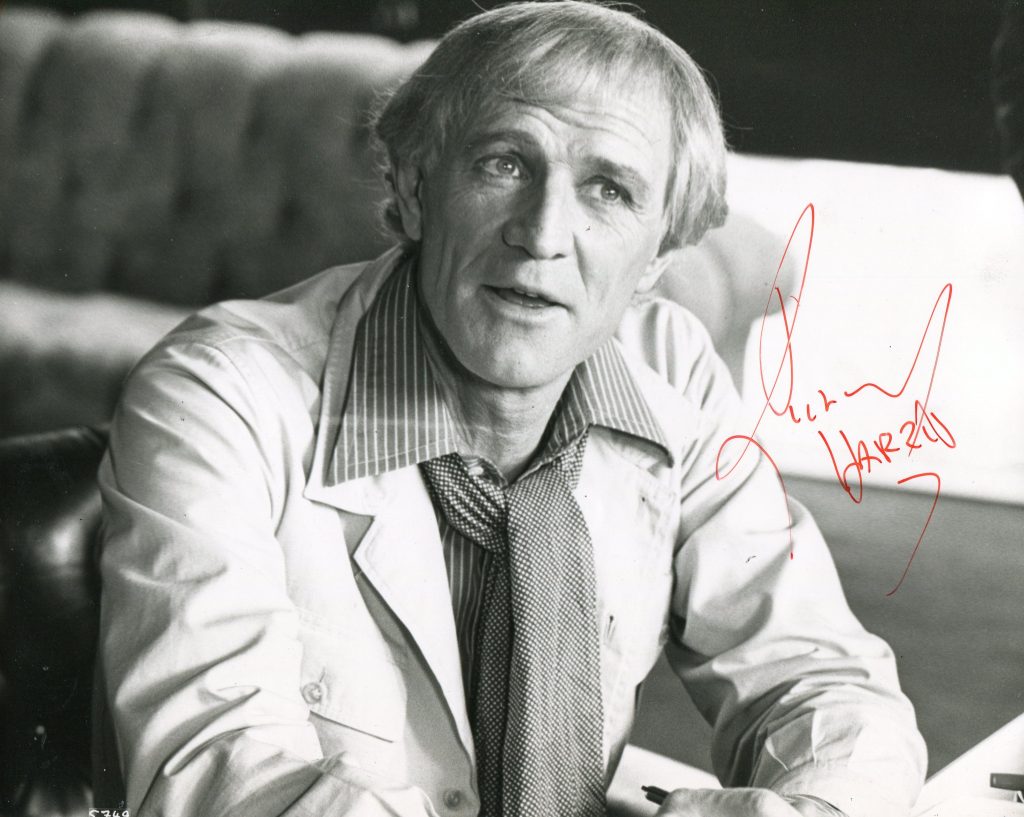

Not that the rumbustious, well-built and fair-haired Harris tried to discourage the public persona of a hard-drinking, hard-living Irishman, hitting the headlines with nightclub brawls and noisy on-set disputes. “There are too many primadonnas in this business and not enough action,” he once remarked.

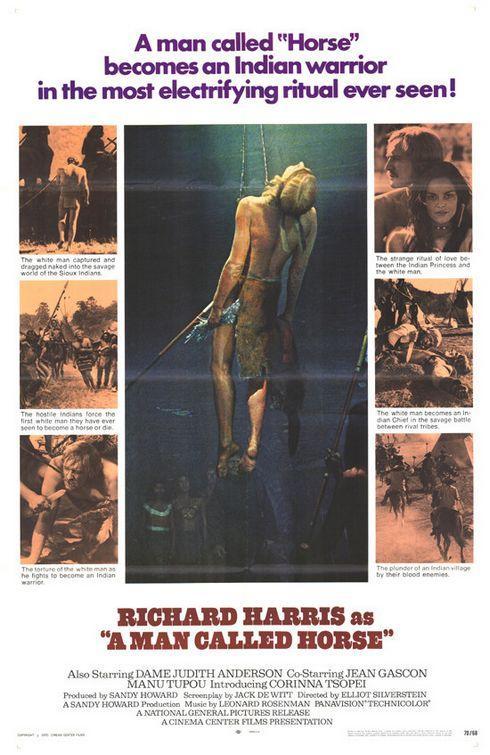

Harris’s careers fell into three phases: the hot-headed, working-class young rebel (This Sporting Life, 1963); the macho masochist (A Man Called Horse, 1970) or fiery action hero (The Wild Geese, 1978); and, finally, the grey-bearded sage.

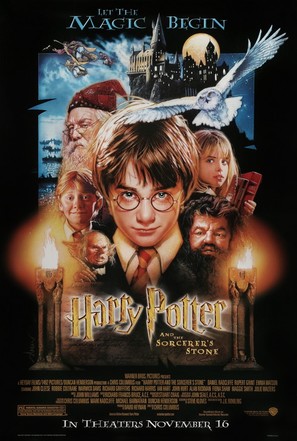

After the less than glorious middle period of the 1970s and 1980s, during which time he had become self-parodic, he won renewed respect for his Oscar-nominated performance as “Bull” McCabe, an irascible farmer fighting to save his land in The Field (1990), and for imposing appearances as the Emperor Marcus Aurelius in Gladiator (2000) and as Albus Dumbledore (also Oscar-nominated) in Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone (2001), a role he repeated in the new Harry Potter And The Chamber of Secrets (2002).

The youngest of nine children born to a Limerick flour-mill owner, Harris studied at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art – Rada turned him down – before joining Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Workshop company, with whom he made his first professional appearance, in Brendan Behan’s The Quare Fellow at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East.

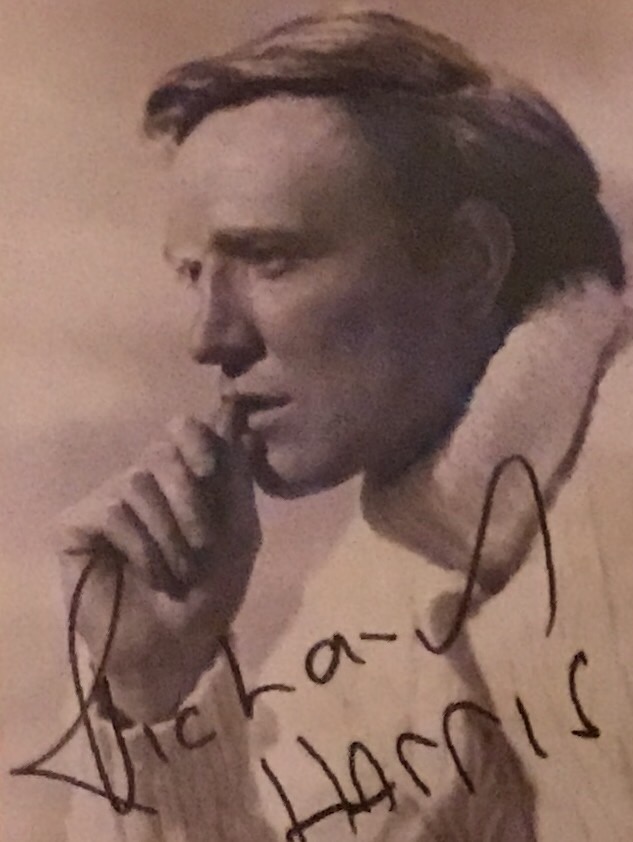

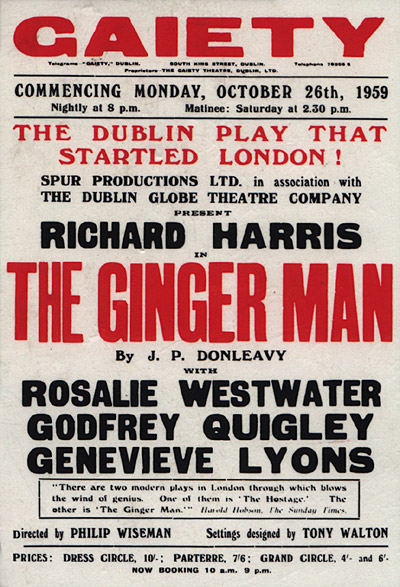

At 26, he made a considerable West End impact in The Ginger Man, adapted by JP Donleavy from his novel, turning the incorrigible louse Sebastian Dangerfield, living in a bedsitter and up to his neck in debt, into a loveable scoundrel.

His film career began at around the same time, initially as the local Lothario in Alive And Kicking (1958), an Irish comedy, although his true strength was not yet fully called upon, even though he played a villain trying to harpoon Gary Cooper in The Wreck Of The Mary Deare (1961), a doughty corporal in The Long And The Short And The Tall (1961) and a leading mutineer in Mutiny On The Bounty (1962).

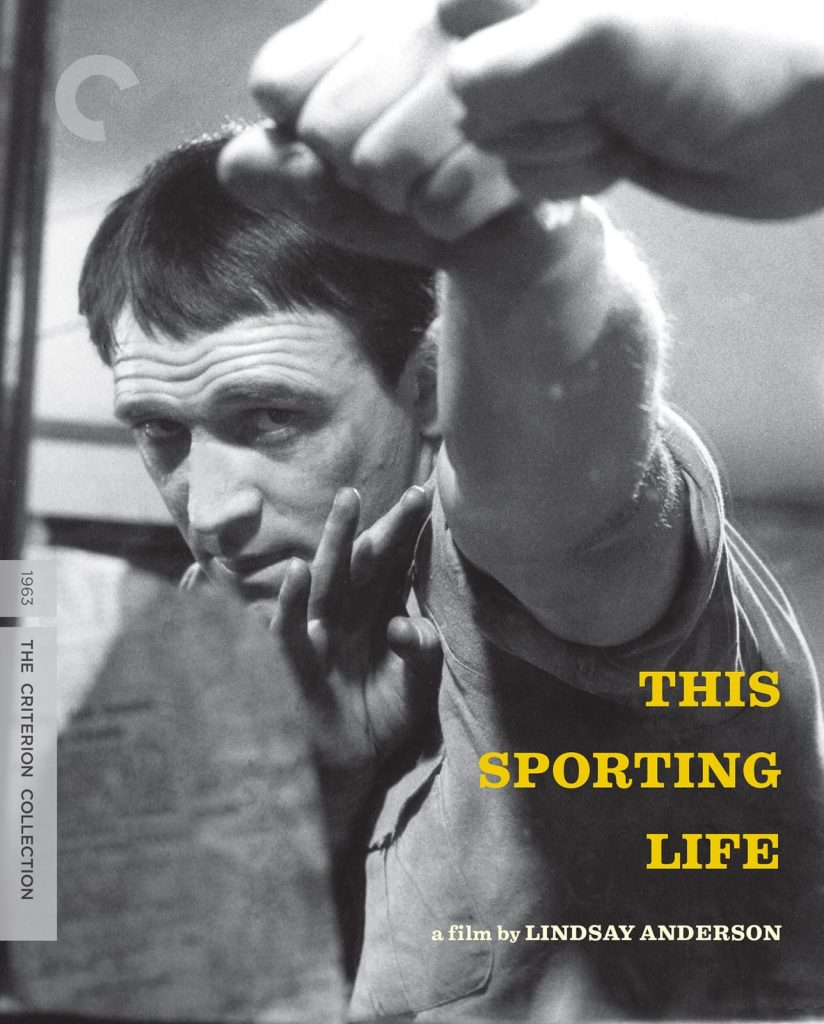

Then Lindsay Anderson, making his first feature, perceptively cast him in This Sporting Life. Harris, whose ambition to become a rugby league professional had been ended by a bout of tuberculosis, was given free rein to display his animalism as Frank Machin, an aggressive and inarticulate rugby player who develops an amour fou for his dowdy and bitter landlady – a relationship as violent as the game he plays.

When she dies, Harris, who provided an emotional power rarely attained in British films, sinks to his knees in mental pain. Pain pervades the film, on the rugby field and in the dentist’s chair, where Machin is having his broken teeth ruggedly extracted. Seven years later, Harris endured worse agony in A Man Called Horse.

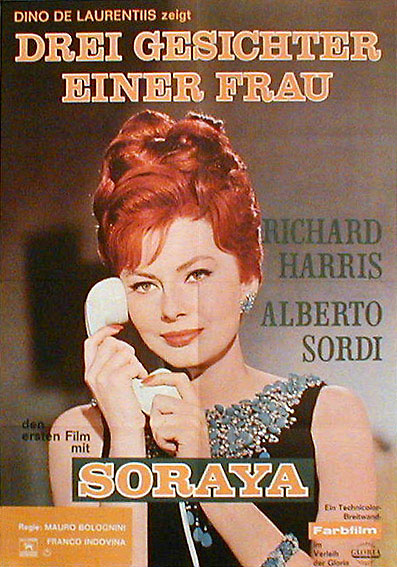

The 1960s saw him becoming an international star. At a time when it was fashionable to cast British actors in Italian films, Michelangelo Antonioni got him to play Monica Vitti’s lover in The Red Desert (1964). Harris, dubbed and adrift in one of his rare introspective roles, hated making the film.

More to his liking was Captain Tyreen, a flamboyant and ambivalent confederate prisoner in Sam Peckinpah’s Major Dundee (1964), clashing – on and off screen – with Charlton Heston. Heston recalled that Harris was “very much the professional Irishman, and an occasional pain in the posterior”; Harris thought his co-star “so square”.

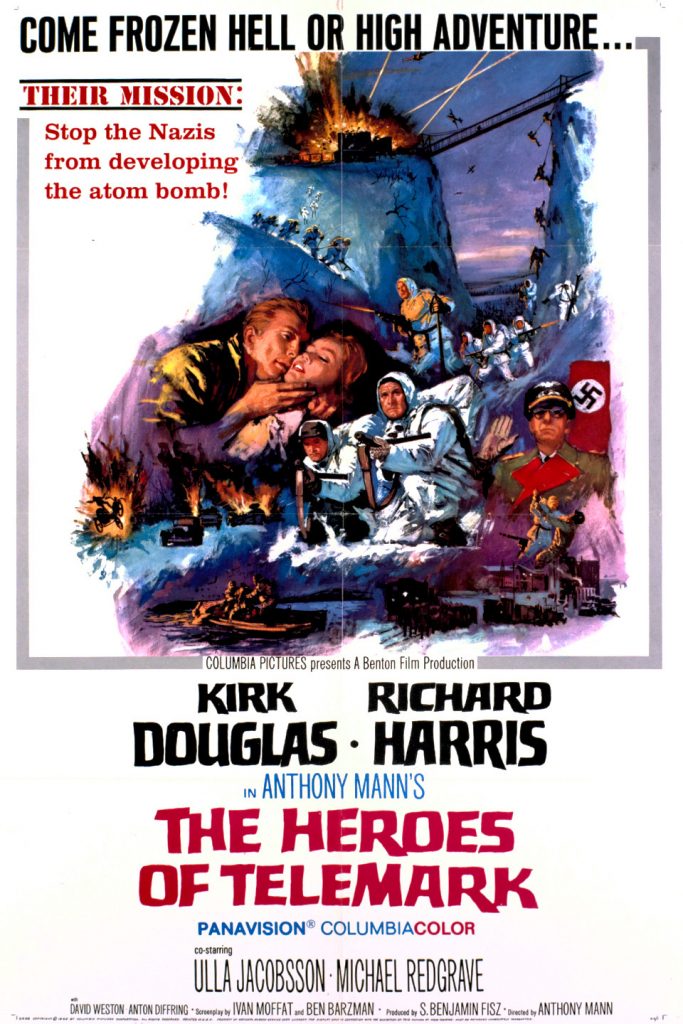

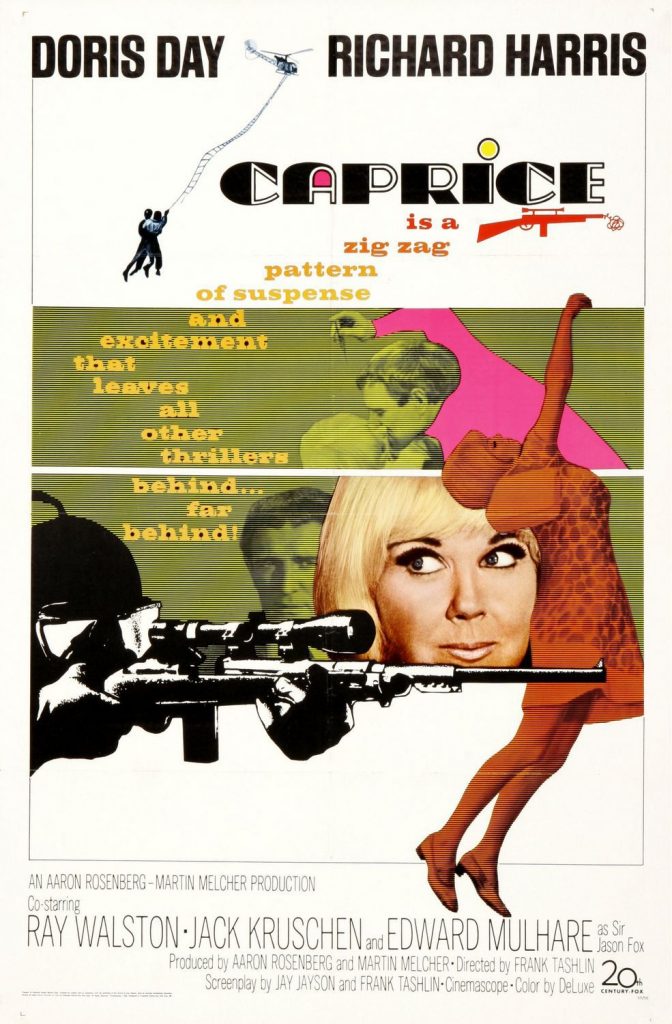

9There followed a mixed bag of parts: a fervent Norwegian resistance fighter in The Heroes Of Telemark (1965); Julie Andrews’s former lover in Hawaii (1966); Cain, in The Bible (1966); and, woefully miscast and seeming to be wearing blue eye shadow as an industrial spy, in Caprice (1967), opposite Doris Day.

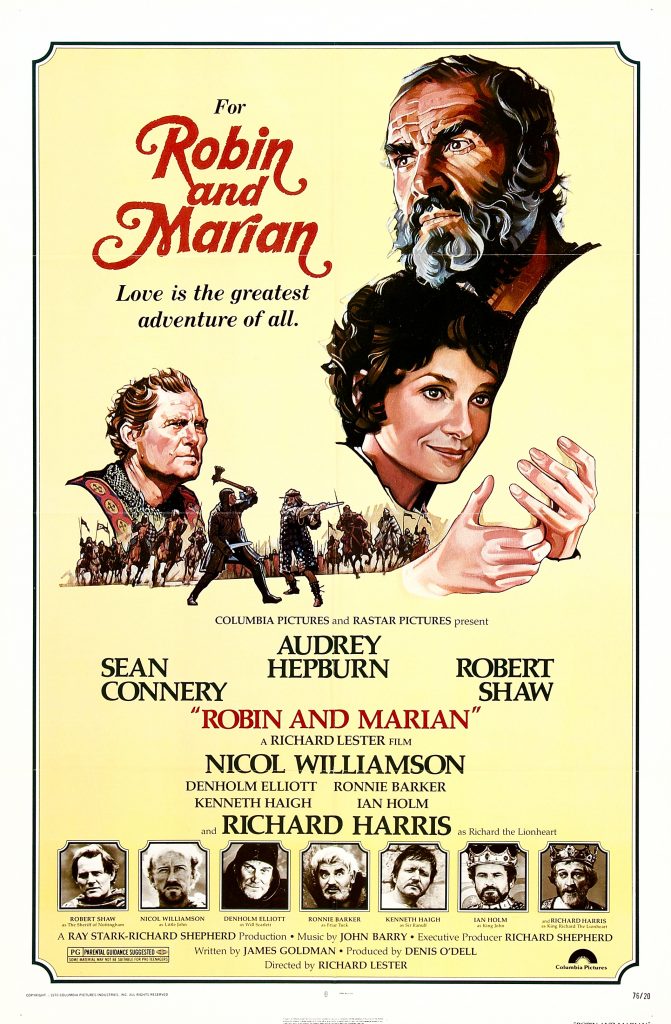

But, in the same year, Harris took one of the most significant roles in his career, which was eventually to make him a multi-millionaire. Although the Lerner-Loewe musical Camelot (1967), in which he portrayed King Arthur with touching sincerity and an acceptable singing voice, was an expensive flop, he would later play the role – created by Richard Burton – many times on stage, both on Broadway and in London in the 1980s, and buy its rights. He also released a hit single – Jim Webb’s MacArthur Park (1968).

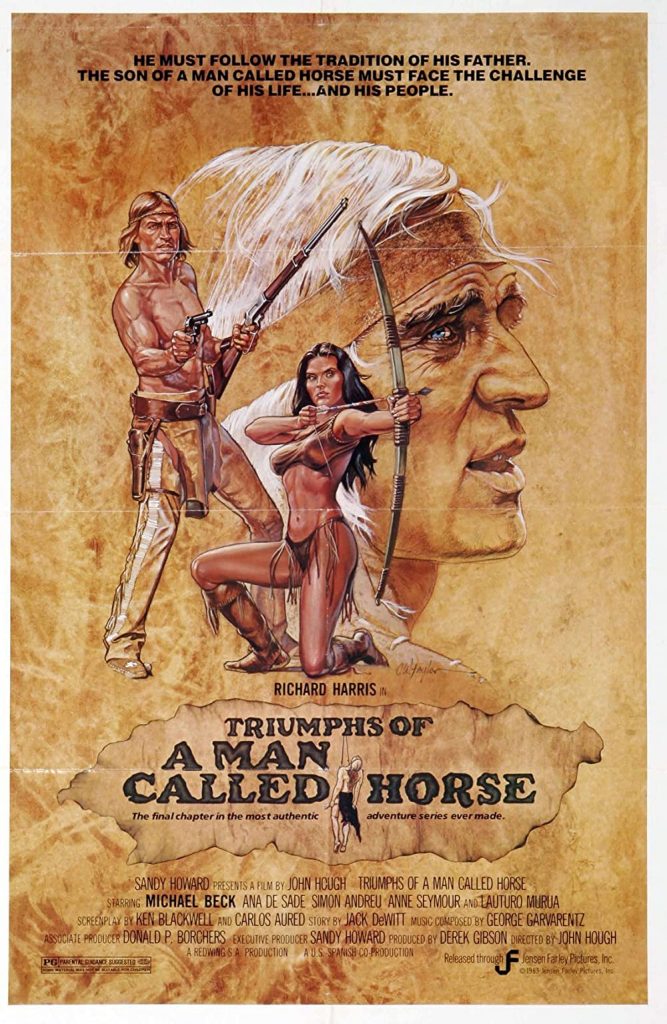

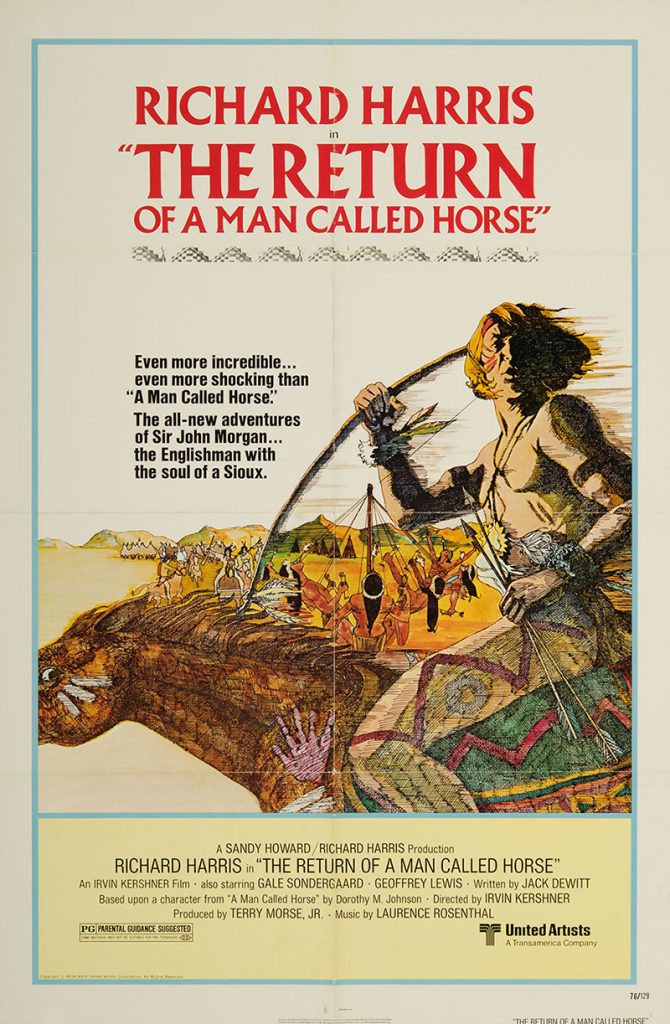

Divorced from his first wife, Elizabeth Rees-Williams, after a 12-year marriage that produced three sons, in 1970 Harris provided a warts-and-all impersonation in the title role of Cromwell, and was A Man Called Horse. The latter was a blond, 19th-century English aristocrat, who, captured by the Sioux, rises from being a beast of burden to espousing their cause. The somewhat pretentious film, and its sequel The Return Of A Man Called Horse (1976), contained a sadistic sun-vow ritual with the hero suspended by clamps from his pectoral muscles.

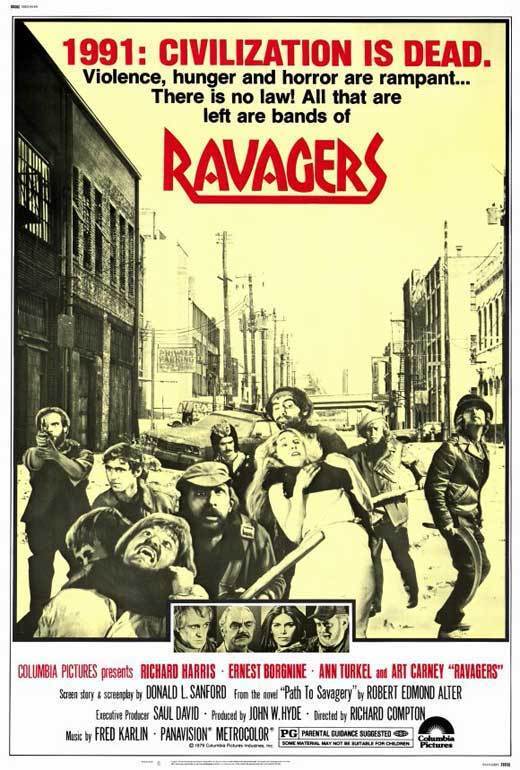

For the rest of the decade, Harris was as visible as he was risible. “I consider a great part of my career a total failure,” he said. “I went after the wrong things – got caught in the 60s. I picked pictures that were way below my talent. Just to have fun.”

Among these pictures were Echoes Of A Summer (1976) as the father of 12-year-old Jodie Foster, dying of a terminal disease; The Cassandra Crossing (1977), a disaster movie in which he tried to counteract a plague on a train; and Orca (1977), where he was a shark hunter incurring the wrath of a killer whale and Charlotte Rampling, to whom he says, “I resent it when a pretty and intelligent woman tells me I’m dumber than a fish.”

There were also two films shot in South Africa at the height of the apartheid era: The Wild Geese (1979), about mercenaries, and A Game For Vultures (1980) ostensibly about political strife in Rhodesia. Then, in the ludicrous Tarzan The Ape Man (1981), Harris struggled to maintain some dignity as the father of Bo Derek’s scantily-clad Jane.

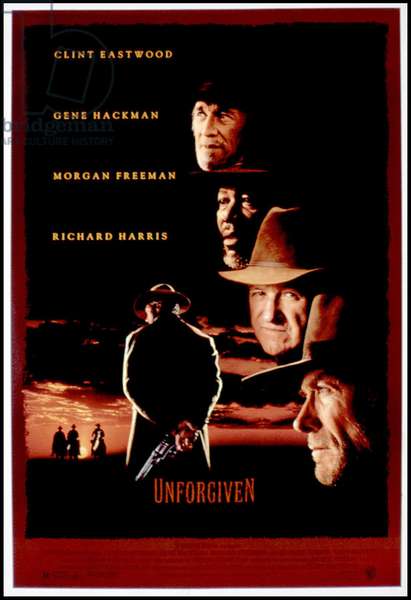

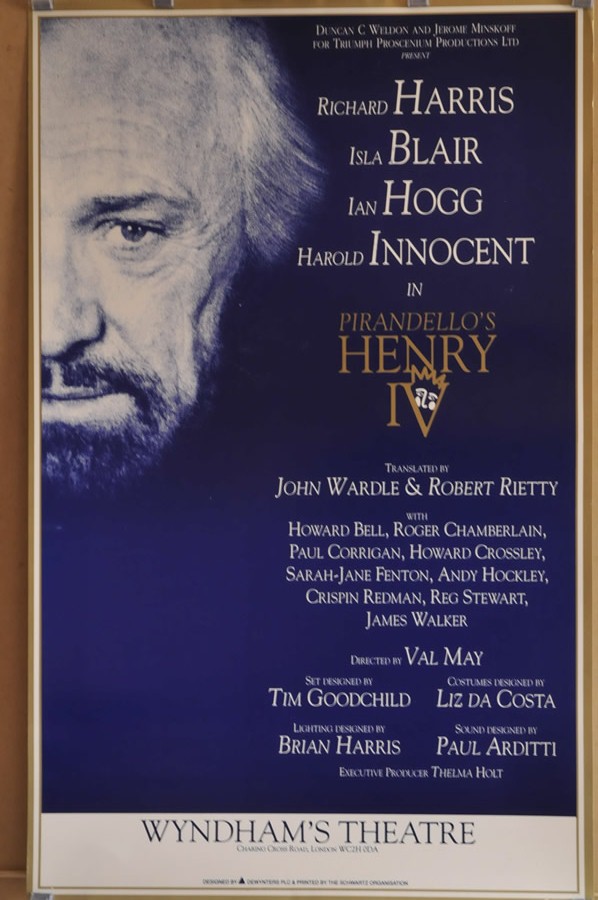

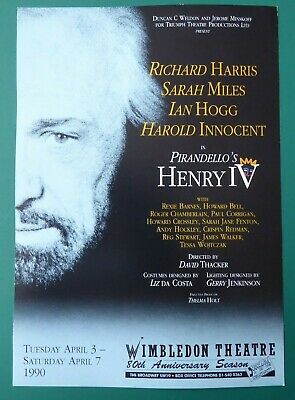

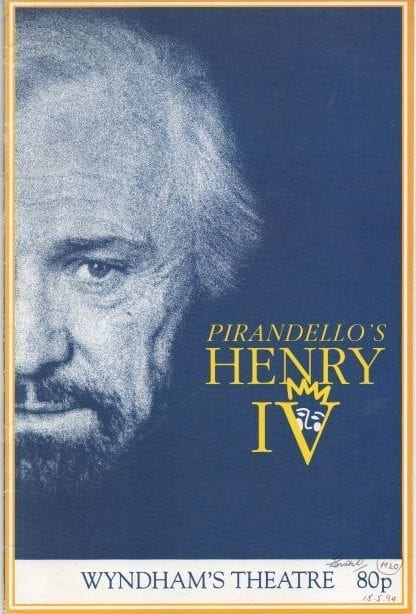

For a while in the 1980s, after divorcing his second wife, Ann Turkel, Harris went into semi-retirement on Paradise Island, in the Bahamas, where he kicked his drinking habit and embraced a healthier lifestyle. It had a beneficial effect. Powerful in the West End run of Piradello’s Henry IV, he made an indelible impression as the dandified killer English Bob in Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992).

Because his granddaughter said she would never speak to him again if he turned down the role of Albus Dumbledore in the Harry Potter series, Harris committed himself to all seven of the films based on JK Rowling’s books. “I’ll keep doing it as long as I enjoy it, my health holds out and they still want me, but the chances of all three of those factors remaining constant are pretty slim,” he remarked.

Despite enjoying his renaissance as one of cinema’s grand old men, Harris, who is survived by his sons Jared, Jamie and Damian, also reflected: “I’m not interested in reputation or immortality, or things like that. I don’t care if I’m remembered. I don’t care if I’m not remembered. I don’t care why I’m remembered. I genuinely don’t care.”

· Richard Harris, actor, born October 1 1930; died October 25 2002The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

Dictionary of Irish Biography:

Contributed by

Harris, Richard St John (1930–2002), stage and screen actor, was born 1 October 1930 in Limerick city, fifth child among six sons and two daughters of Ivan Harris, a prosperous flour‐mill owner, and Mildred Harris (née Harty). Reared in a comfortable, middle‐class home at Overdale, Ennis Road, Limerick, he attended the Jesuits’ Crescent College. Rebellious and lacking in academic ambition, he was frequently in trouble at school, which he left without sitting the leaving certificate, thereafter working desultorily in the family business. Highly accomplished in sport, especially rugby, he played on the first Crescent side to win the Munster schools’ cup (1947), and on the Garryowen side that won the 1952 Munster senior cup. Competing in inter‐provincial junior cup matches, he had ambitions to play senior rugby at international level. These hopes were dashed when he contracted tuberculosis, which enforced a lengthy two‐year convalescence (1953–5), largely confined to bed in the family home, passing the time by reading avidly and widely. Devouring Shakespeare and the range of modern fiction and drama, he conceived a desire to pursue a career in the theatre (having previously flirted with amateur dramatics). Moving to London in 1955 on a small legacy in Guinness shares from an aunt, he initially intended to study directing, but failed to find a suitable course. Rejected by the Central School as too old, he studied acting at London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA), one of the few London drama schools then including study of Stanislavksy, whose works had informed his self‐education.

His gifts of improvisation impressed Joan Littlewood, who cast him, in his London stage debut, in the first production (1956) of ‘The quare fellow’, the prison‐yard drama by Brendan Behan (qv); as the young prisoner Mickser, Harris intoned the play’s curtain‐raising song, ‘The auld triangle’. Throughout the later 1950s he pursued an exciting stage apprenticeship as a regular member of Littlewood’s path‐breaking Theatre Workshop at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East, and in productions of other companies. He attracted wide notice as the anarchic scoundrel Sebastian Dangerfield in ‘The ginger man’ (1959), J. P. Donleavy’s stage adaptation of his own novel. Initially intended for the main supporting role, Harris insisted that he was born to play the lead: ‘It’s me. It’s my life.’ He made his professional Irish stage debut when the play was brought to Dublin’s Olympia theatre (October 1959) by Godfrey Quigley (qv), and delighted in the ensuing controversy: the run was cancelled after three days when author and cast refused to make cuts demanded by a management intimidated by morally outraged press reviews.

Harris’s film debut came in a minor role in the comedy Alive and kicking (1958). In his early supporting film roles he was usually typecast as the impulsive young rebel, oozing machismo, and chafing under the restraints imposed by effete, cautious superiors. He appeared in two films shot at Ardmore studios, Bray, Co. Wicklow, Shake hands with the devil (1959) and A terrible beauty (1960), and made his Hollywood debut opposite Gary Cooper in The wreck of the Mary Deare (1959). He was included in the stellar cast of the international blockbuster The guns of Navarone (1961), and played the disgruntled, impetuous seaman John Mills in the lavish remake of Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), on the set of which in Tahiti he famously locked horns with Marlon Brando, once his adolescent idol.

Harris’s breakthrough came in This sporting life (1963), the feature‐film directing debut of Lindsay Anderson, and one of the landmarks of early 1960s British social realist cinema. As the period’s quintessential ‘angry young man’, Harris played an inarticulate, brutishly violent, but emotionally vulnerable Yorkshire coalminer turned professional rugby league player, who becomes involved with his flinty widowed landlady, played by Rachel Roberts. In an uncompromisingly authentic portrayal, Harris captured his character’s fundamental masochism, both physical and emotional, disguised as hardnosed, manly stoicism. The performance won him the best actor award at the 1963 Cannes film festival, and an Academy award nomination. He obtained starring roles under two of the decade’s most important film directors, Michelangelo Antonioni on The red desert (1964), and Sam Peckinpah on Major Dundee (1965).

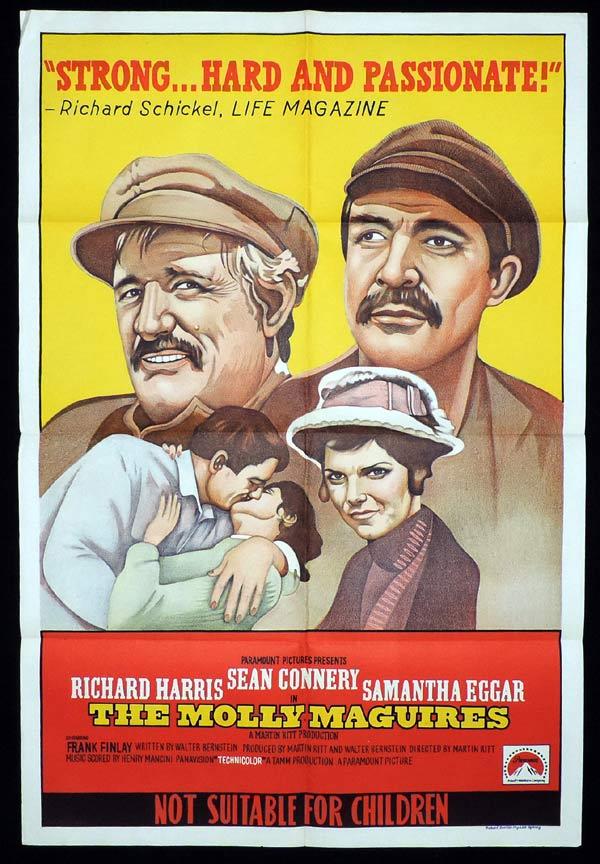

In the mid 1960s Harris’s international film career took off; a hot property, commanding hefty fees, he took a pot‐pourri of roles in largely mediocre pictures, claiming a wish to be as versatile an actor as possible. After lobbying obsessively, he landed the plum role of King Arthur in the movie version of the hit stage musical Camelot (1967). The performance having revealed an acceptable singing voice, he embarked on a parallel career as a pop singer. His recording of Jimmy Webb’s enigmatic, seven‐minute single ‘MacArthur Park’ was a transatlantic chart hit in summer 1968, which he followed with two LPs, A tramp shining (1968), an album of Webb compositions, and The yard went on forever (1968). Over the next five years he recorded several more LPs, released eight singles, and performed a concert tour with the Phil Coulter orchestra (1972). He ended the 1960s with two arresting screen performances. He was a reluctant police informer opposite Sean Connery’s miners’ leader in The Molly Maguires (1969). In A man called Horse (1970) – an unconventional western that proved a surprising box‐office success, and attained cult status – he played a footloose English aristocrat on an American hunting expedition in 1825 who is captured by Lakota Sioux; the performance was famous for the gruesome, but inaccurate, depiction of the Lakota sun‐dance ritual. He subsequently appeared in two execrable sequels, Return of a man called Horse(1976) and Triumphs of a man called Horse (1982). He took his only turn in the director’s chair on Bloomfield (1971), in which he also starred, as a soccer player in decline. The previous year (1970) he had played Oliver Cromwell (qv) in Ken Hughes’s Cromwell.

Throughout these years Harris was notorious for a hectic, drink‐fuelled, hell‐raising lifestyle, sensationally reported (and often exaggerated) in tabloid journalism. Volatile and pugnacious, he made frequent headlines with drunken brawls, scrapes with the law, marital storms, and a penchant for flamboyantly eccentric, hippie‐style attire. In the early 1970s he resided in London in Tower House, a sprawling Victorian neo‐gothic mansion, before moving in the mid 1970s to a property on Paradise Isle in the Bahamas, which he retained till his death. Warned by doctors that he had eighteen months to live if he continued drinking, after bidding farewell to alcohol in August 1981 with two bottles of Chateau Margaux 1947 (at $325 each), he remained dry for over a decade, before returning to the occasional dietary Guinness.

During the 1970s he appeared in a multitude of average to poor films, marketing his celebrity for massive pay cheques, ‘as visible as he was risible’ (Guardian obit.). In the 1980s he all but ceased film acting. He returned to the stage in a revival of ‘Camelot’, which toured America to sell‐out houses (1981–2), and played less successfully in London (1982–3). The stage show was filmed and screened by HBO in the USA (1982). Having purchased the rights to the stage production, he augmented his already considerable personal wealth into the multimillions by taking the show on an extremely lucrative world tour. For a mesmerising performance on the London West End and a British tour in ‘Henry IV’ by Luigi Pirandello, Harris won the London Evening Standard theatre award for best actor (1990–91). The role coincided with the artistic resurrection of his film career, as the ‘Bull’ McCabe in The field (1990), adapted from the play by John B. Keane (qv), and directed by Jim Sheridan. In a saga of land hunger and vengeance in Co. Kerry, Harris played an obstinate, turbulent, tragic character with a commanding performance, for which he won a second Oscar nomination. Referring to the Shakespearean roles that he had once aspired to play, he remarked that if This sporting life was the Hamlet of his career, the ‘Bull’ McCabe would be his Lear. The role inaugurated the finest sustained period of his career in cinema, as he chose exacting roles in worthy productions, performed with appropriate blends of passion and restraint, inflected with the gravitas of age. His credits included a weathered gunslinger in Clint Eastwood’s iconoclastic western Unforgiven (1992), an Irish traveller patriarch in Trojan Eddie(1996), and a magisterial Marcus Aurelius in Ridley Scott’s Oscar‐winning Gladiator (2000). He exuded beguiling charm as the wise and benign wizard Albus Dumbledore in Harry Potter and the sorcerer’s stone (2001), reaching the largest audience of his career in the second biggest hit in cinematic history (after Titanic); after thrice turning down the role, he relented when his eleven‐year‐old granddaughter threatened never to speak to him again. He reprised the role in Harry Potter and the chamber of secrets(2002), released three weeks after his death. His last leading role was in My kingdom (2002), directed by Don Boyd, as a Lear‐like gangster chieftain in contemporary Liverpool, for which he was nominated for best actor at the British Independent Film Awards.

Through a remarkably uneven career, Harris made over seventy‐five movies. Tall, burly, and broad‐shouldered, he filled the screen as a massive, brooding physical presence, noted for a throaty vocal delivery (‘a man called hoarse’, some quipped). Ireland’s first global cinema star, he was as famous for his legendary off‐screen escapades as for his performances. Revelling in his own image, he could be defiant, outspoken, and cantankerous, but also immensely entertaining as a self‐deprecating raconteur, exuding a boyish sense of fun. He dismissed criticism of career decisions more commercial than artistic with unconvincing deprecation of the actor’s craft, and replied to critics who charged that he had for too long squandered his talent by asserting ‘I didn’t fulfil their idea of my talent’ (quoted in Independent obit.). Remaining a passionate supporter of Irish and Munster rugby, he was a familiar face in the stands at Lansdowne Road and Thomond Park, and remarked that he would gladly swap all his acting accolades ‘for one sip of champagne from the Heineken Cup’ (quoted on IMDB).

Harris married first (1957) Elizabeth Rees‐Williams, a 20‐year‐old London acting student, only daughter of Lord Ogmore, a liberal peer; they had three sons. They divorced in 1969, some years after separating, but remained on friendly terms. He married secondly (1974) Ann Turkel, an American fashion model and aspiring actress, who later pursued a career as a photographer; they had no children, and divorced in 1981. During his last decade he lived in a luxurious suite in the Savoy hotel, London. After falling ill with Hodgkin’s disease, and receiving chemotherapy, he was hospitalised with a chest infection in August 2002. He died 25 October 2002 in the University College Hospital, London. After a private family funeral, his ashes were scattered at his home in the Bahamas.

Sources

Michael Feeney Callan, Richard Harris: a sporting life (1990); Gus Smith, Richard Harris: actor by accident (1990); Tom and Sara Pendergast (ed.), International dictionary of films and filmmakers, iii: Actors and actresses (2000 ed.), 533–6; Guardian, 26 Oct. 2002; Ir. Times, 26, 28 Oct., 2 Dec. 2002; Sunday Times (Ir. ed.), 27 Oct. 2002; Daily Telegraph, 28 Oct. 2002; Independent (London), 28 Oct. 2002; Times, 28 Oct. 2002; Michael Feeney Callan, Richard Harris: sex, death, and the movies: an intimate biography (2003); Cliff Goodwin, Behaving badly: the life of Richard Harris (2003); Internet Movie Database, www.imdb.com (accessed 7 June 2006); ODNB online