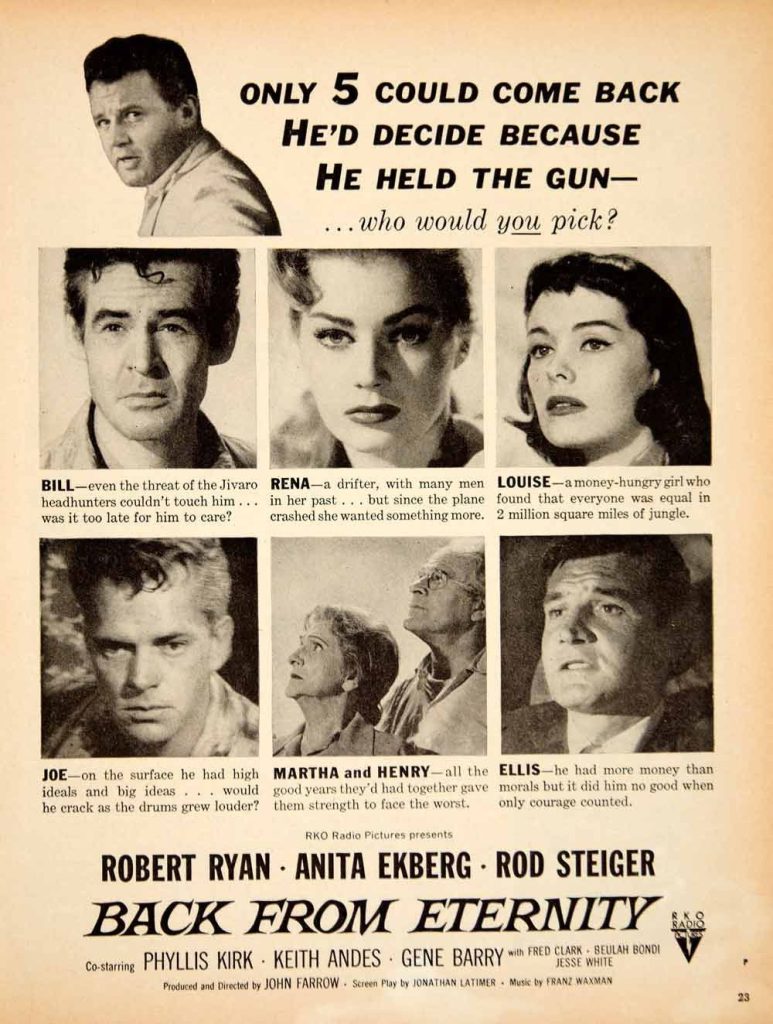

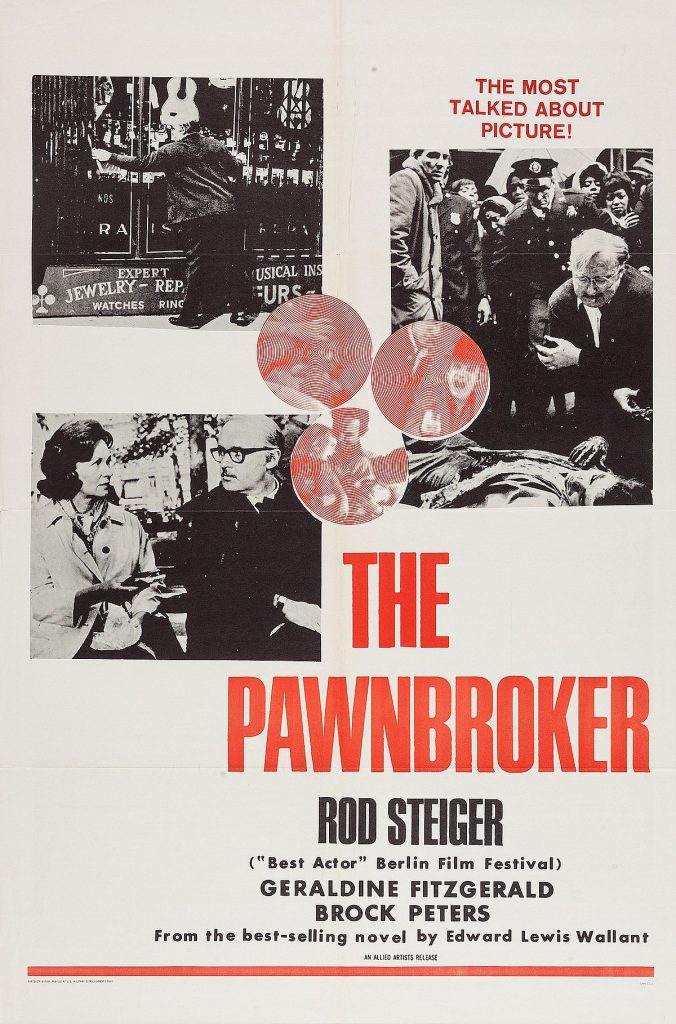

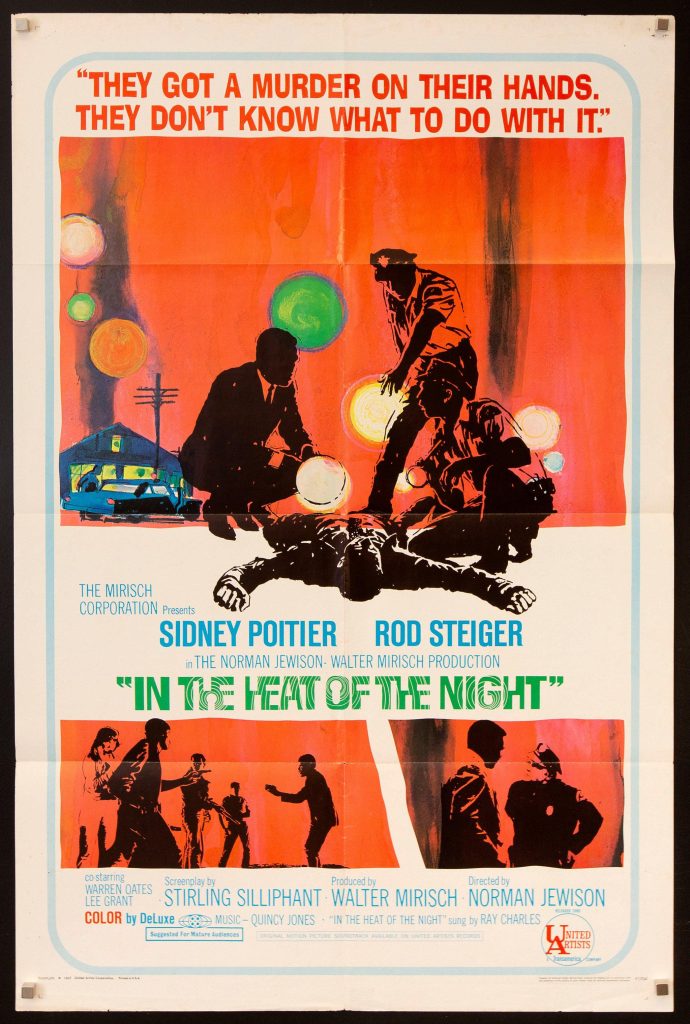

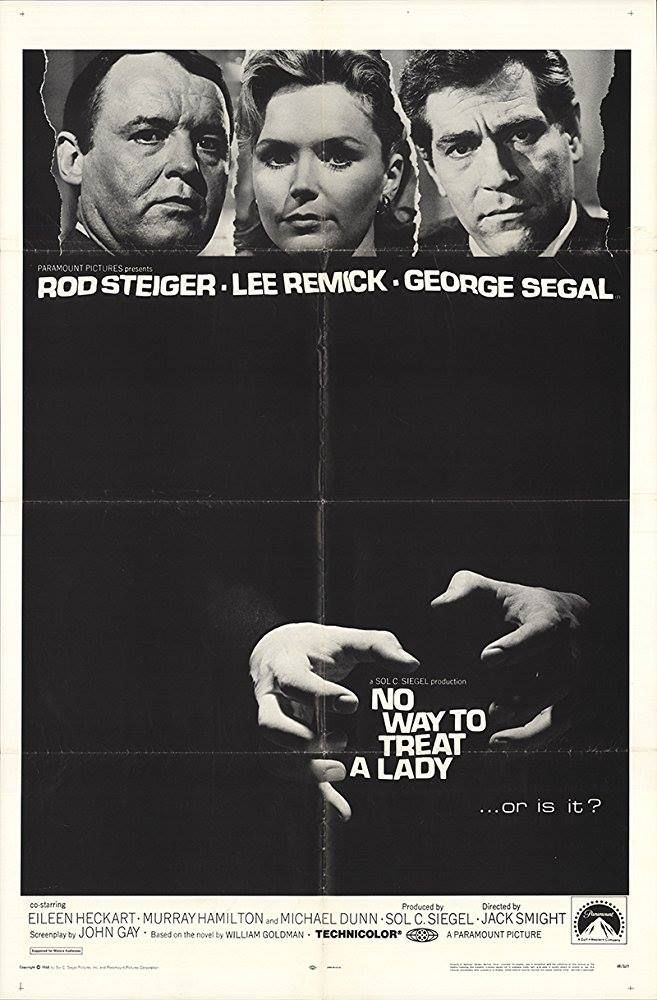

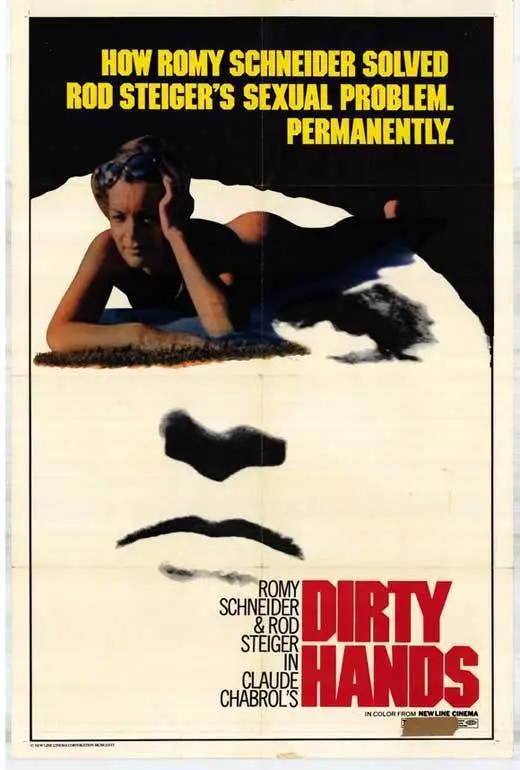

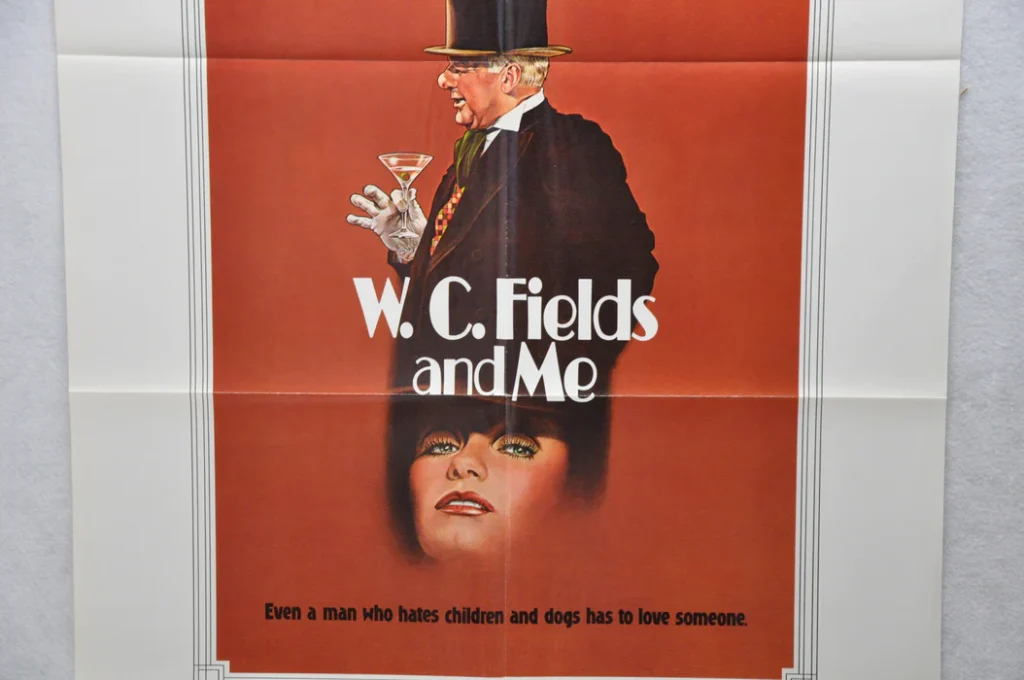

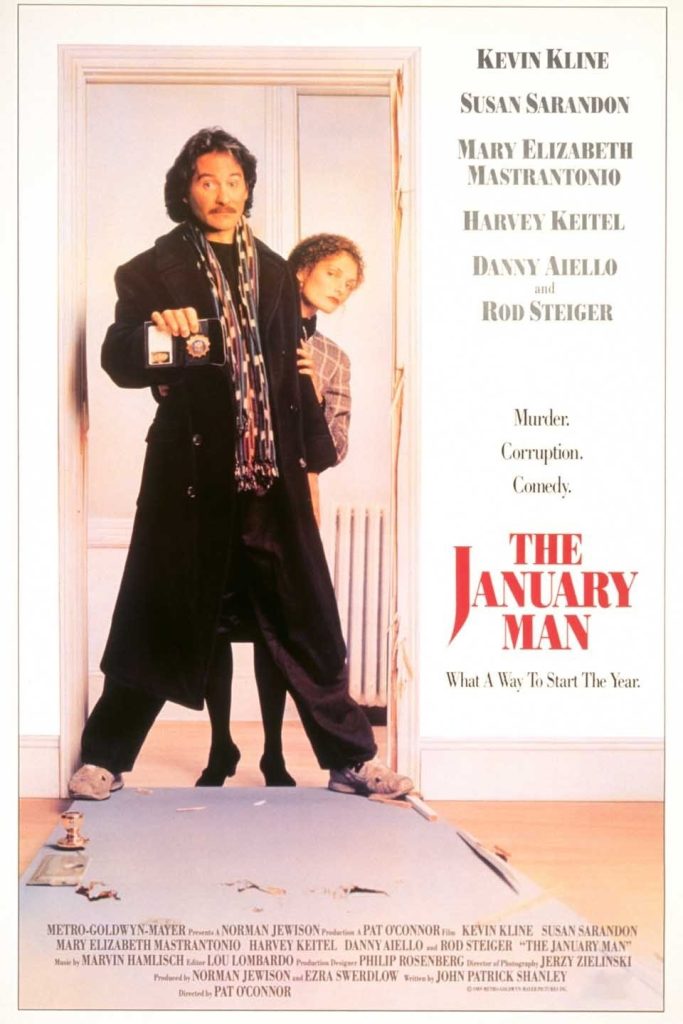

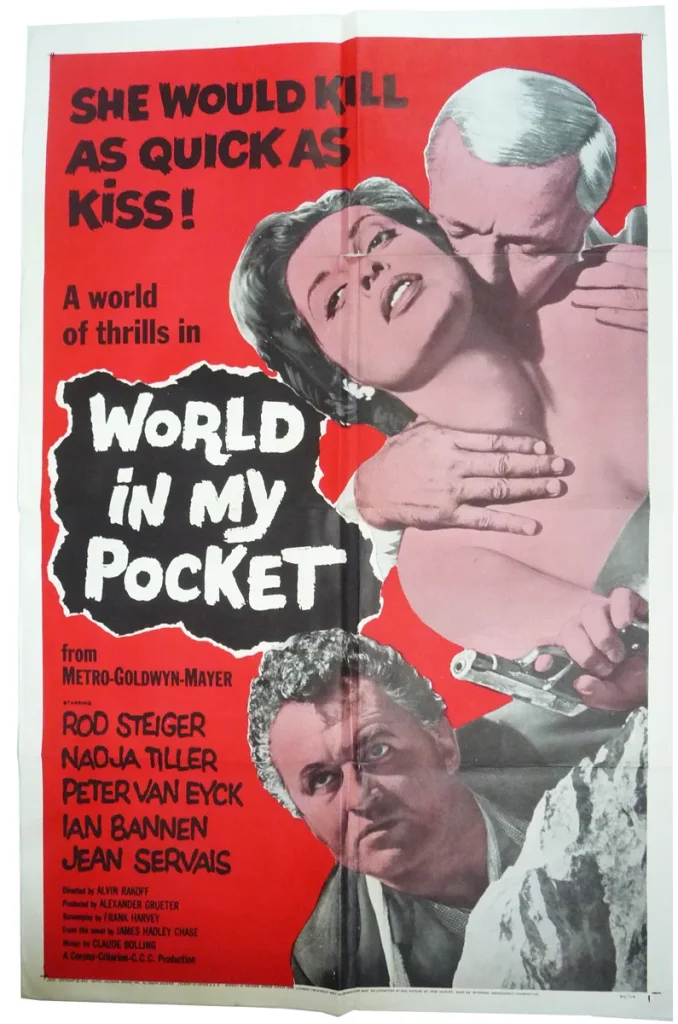

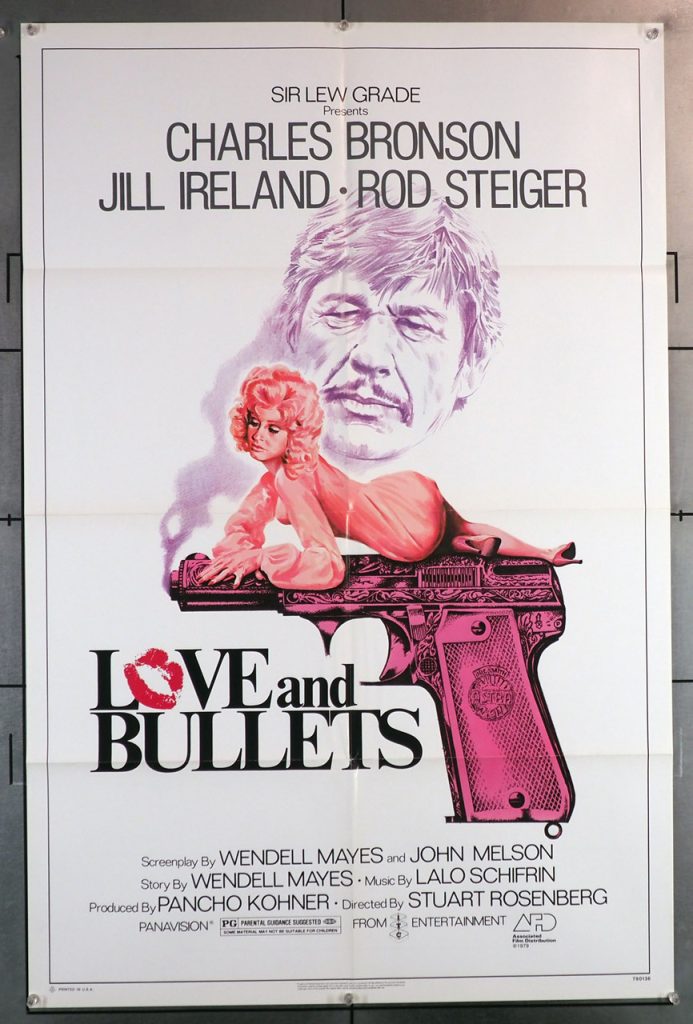

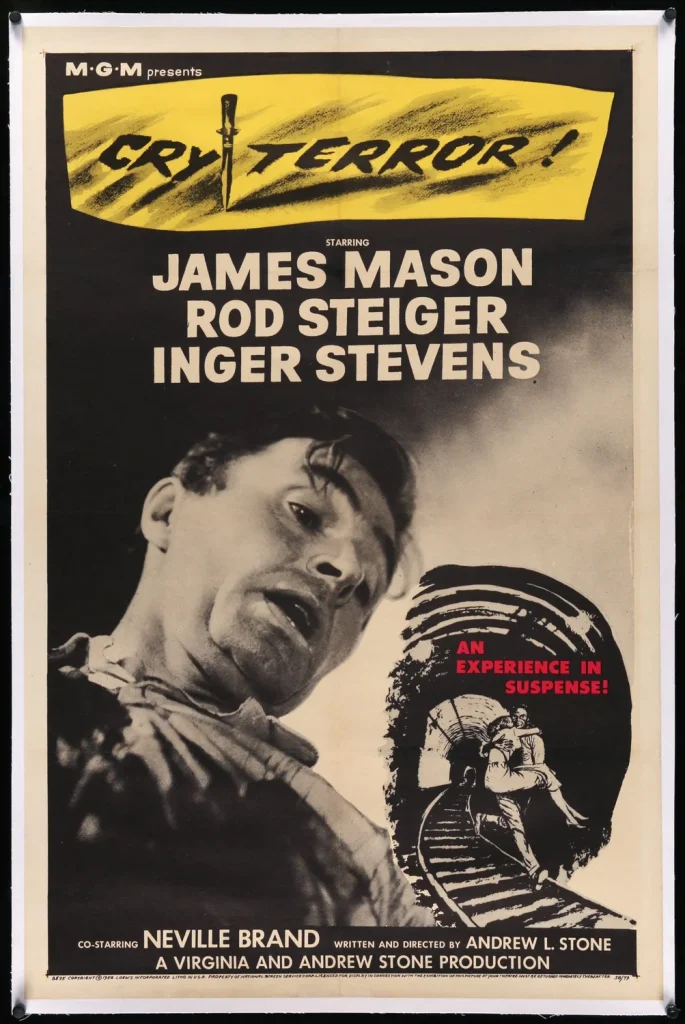

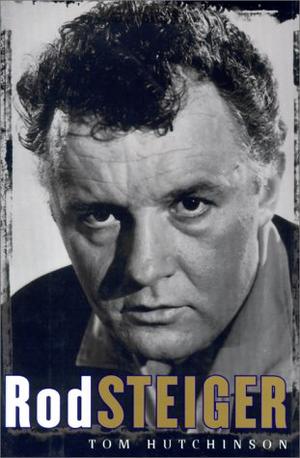

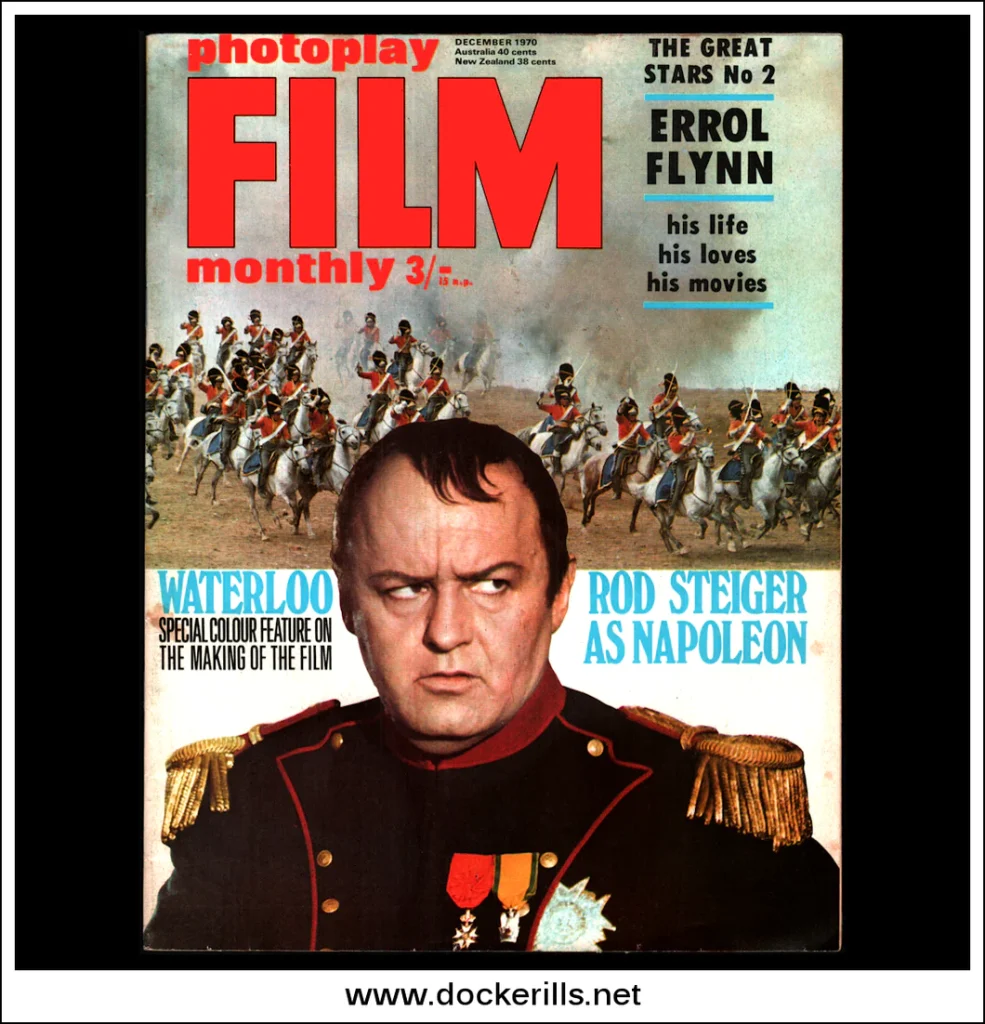

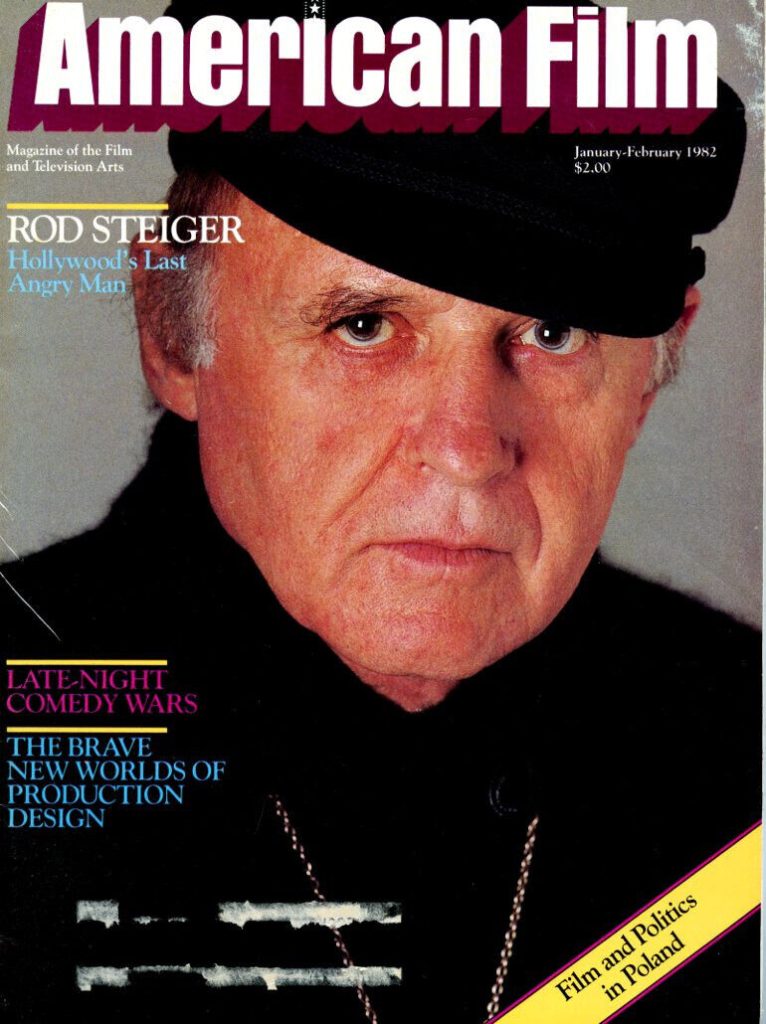

The 1960’s were Rod Steiger’s decade. He seemed to feature in many of the major films of the period. He was born in New York in 1925. He made his debut in Fred Zinnemann’s “Teresa” with Pier Angeli and John Ericson in 1951. His other films included “On the Waterfront”, “Oklaholma”, “The Big Knife” and “Cry Terror”. His 1960’s films included “The Pawnbroker”, “In the Heat of the Night” and “No Way to Treat A Lady”. Rod Steiger died in 2002.

Philip French’s “Guardian” obituary:

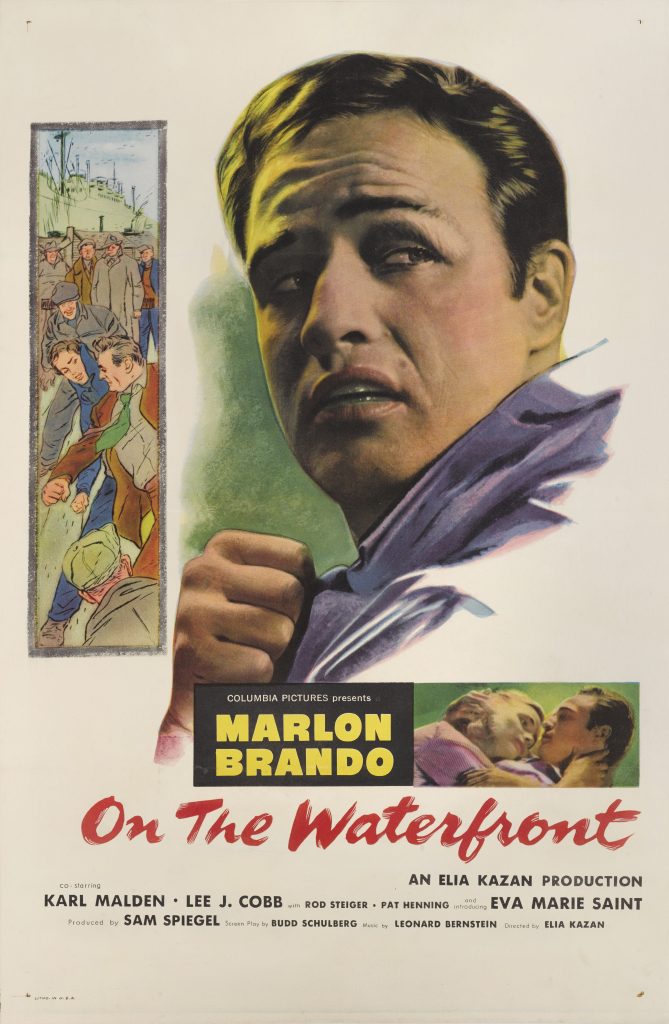

Rod Steiger, who has died at the age of 77 was, with his fellow Actors Studio graduate Marlon Brando, the screen’s greatest exponent of the Stanislavski Method, whereby a performer digs deep into himself and the supposed history of the character he is playing to find the essence of the role. Appropriately, the most memorable single scene in which either appeared (one of the greatest in movie history) was their heartbreaking dialogue in the back of a taxi in Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954) as the crooked lawyer Charley Malloy and his punch-drunk younger brother Terry. It ends with the guilt-ridden Steiger going to meet his death, and the redeemed Brando heading for salvation.

On the Waterfront is set in squalid urban New Jersey, where Steiger grew up caring for his alcoholic mother after his father, a third-rate vaudevillian, deserted the family at the height of the Depression. Immediately after Pearl Harbour, the 16-year-old Rod joined the navy, giving a false age, and served in the Pacific.

He began acting while on a postwar shore assignment, before enrolling under the G.I. Bill at drama school – a decision that transformed his life. Like John Frankenheimer, who died on 6 July, he got his first real break during the Golden Age of live TV drama in New York and, like Katy Jurado, who also died a week ago, he got his first Hollywood role, a very small one, in a Fred Zinnemann movie.

Steiger was a stocky, bull-necked man with piercing eyes, a brooding presence and an aggressive body language, and his adult life – recurrent depression, four turbulent marriages, heavy drinking, chronic overeating, a tendency to violence – was as troubled as his childhood.

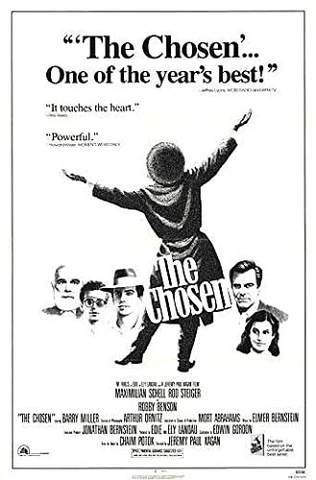

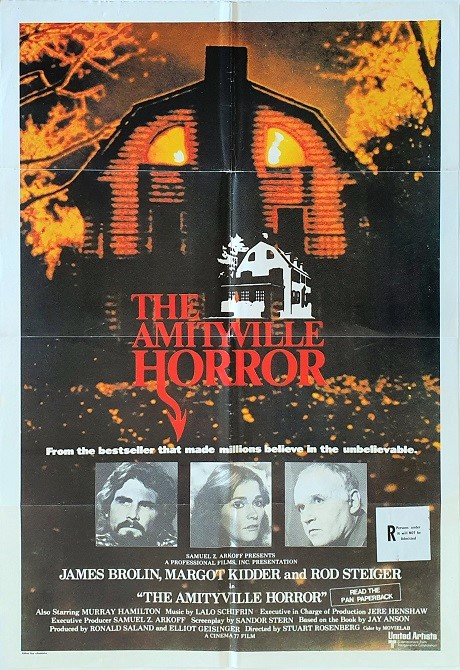

But if he was an alcoholic, he was also a workaholic, and brought to the playing of a wide range of roles a complex personality, a terrible sense of pain, a burden of guilt, an intense self-interrogation, an obsession with authenticity. He poured so much into his characters that they often overflowed with an excess of emotion. This was the case with his melancholic Jud Fry in Oklahoma! and the string of deranged priests and preachers he played (eg The Amityville Horror, The Ballad of the Sad Café), though one of his best, least-vaunted performances was the unyielding Hasidic rabbi in The Chosen.

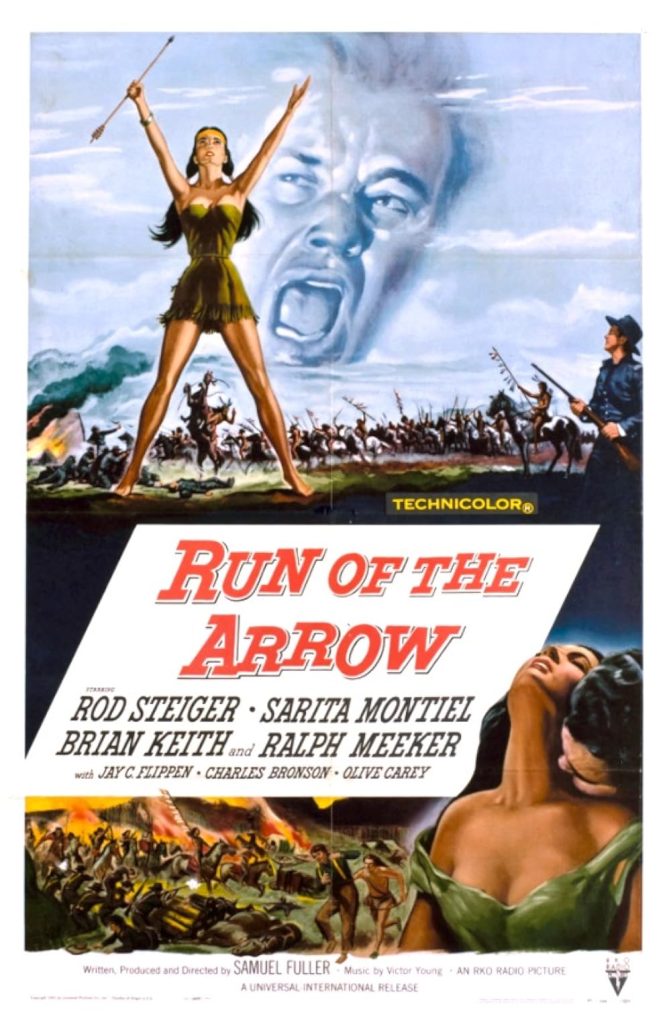

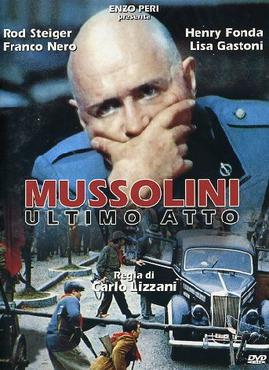

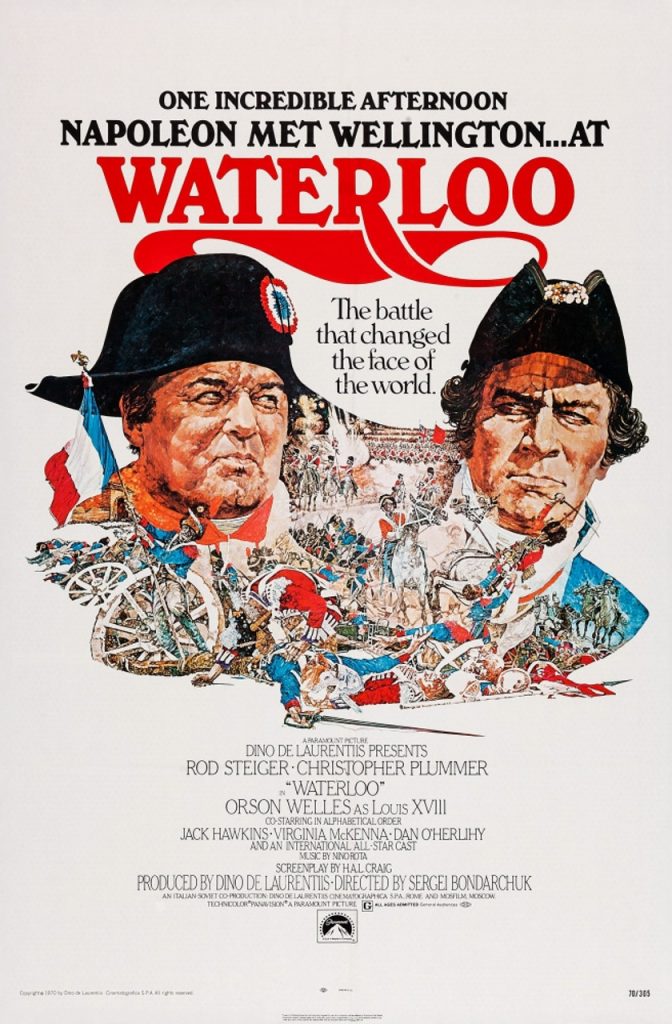

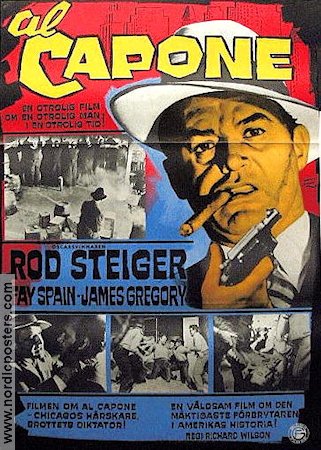

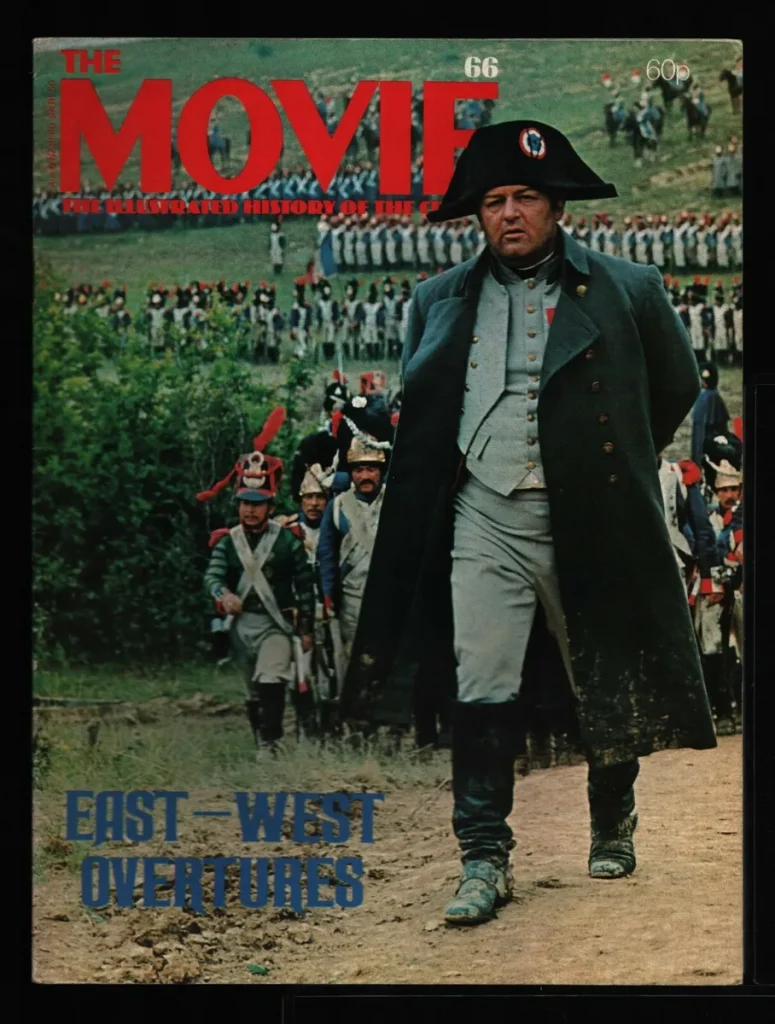

He won an Oscar for his most popular role as the small-town Mississippi police chief in In the Heat of the Night, a dim redneck who comes to respect, and be respected by, black detective Sidney Poitier. But he was equally good as the Irish-American soldier in Run of the Arrow, who refuses to accept the South’s defeat in the Civil War and goes West to discover himself among the Sioux, and as the tormented Auschwitz survivor living an embattled life in Harlem in The Pawnbroker. In less sympathetic vein, he was superb as the Neapolitan racketeer in Francesco Rosi’s Hands Over the City and the ruthless Hollywood mogul in The Big Knife. But he always found an element of humanity in the worst people he played, including Al Capone, perhaps the best of his gallery of historical portraits.

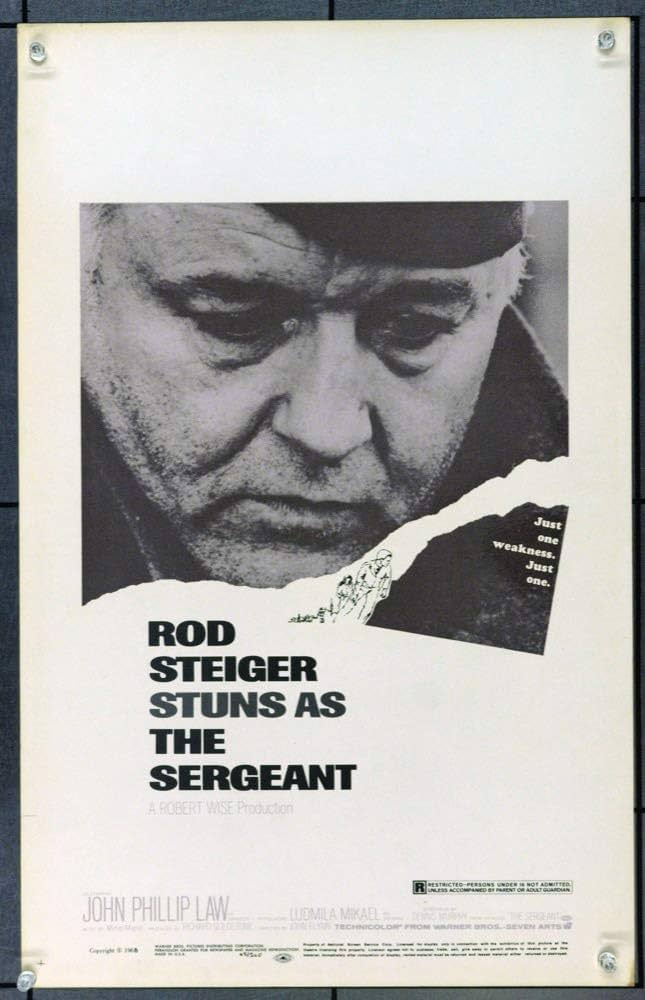

Yet, given the chance, which wasn’t often, he could be very funny, especially as the mother-fixated serial killer in the black comedy No Way To Treat a Lady who, like the repressed homosexual soldier he played in The Sergeant, shows the daring he often exhibited.

Sadly, that daring didn’t extend to reprising on the big screen the TV role he created in Marty or accepting the title role in Patton: Lust for Glory, which won Oscars for, respectively, Ernest Borgnine and George C Scott.

Rod Steiger: born 14 April 1925, died 9 July 2002

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

Comments

Ashley Tschudin

Hi Liam – I am writing to you after being heartbroken reading this post as Rod is my grandfather. You have a lot of factually incorrect information in this blog and I would like the opportunity to clear some facts up for you. Please reach out to me via email. Thank you.

Liam

Hi Ashley. I am a big Rod Steiger fan and am sorry that you did not like the post which is an obituary from “The Guardian” newspaper, a reputable publication in the U.K. if y;u would like to send me your own tribute on your grandfather and I will upload your tribute and take down the “Guardian” obituary.

Kind regards