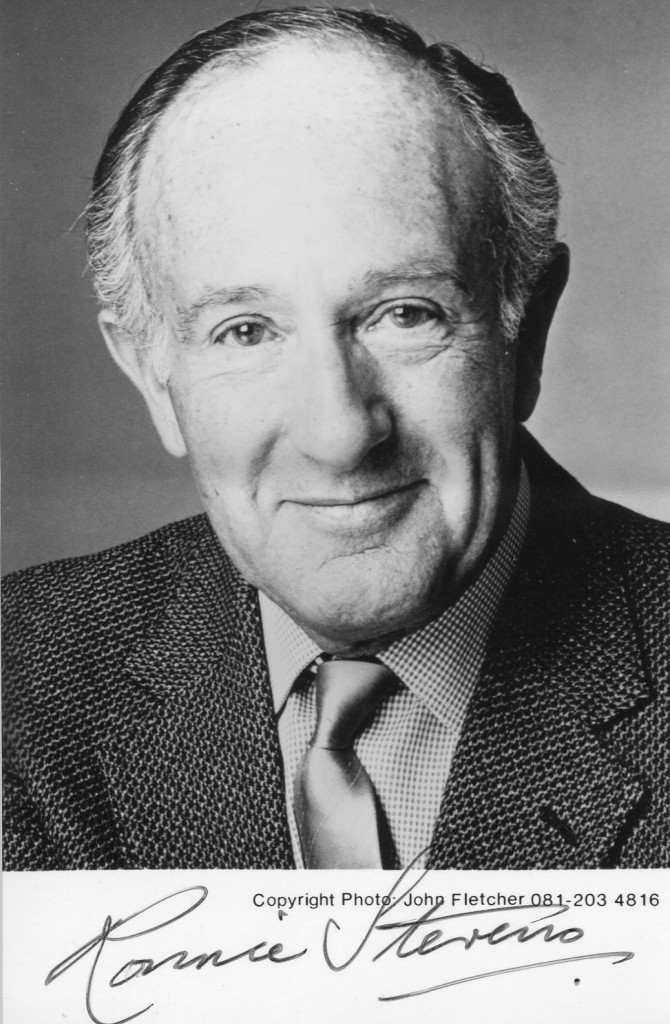

Ronnie Stevens was born in London in 1925. His film debut was in 1952 in “Top Secret”. Film Career highlights include “Doctor At Large in 1957, “On the Beat” in 1962 and his final movie “The Parent Trap” in 1998. He died in 2006.

“Guardian” obituary:

The following correction was printed in the Guardian’s Corrections and clarifications column, Friday November 17, 2006

The article below said in error that the actor Ronnie Stevens is survived by his two sons. His eldest son, Paul, died in 1990. He is survived by his youngest son, Guy, and grandson Jake. In addition, he died on November 11, not 12. Apologies to family and friends.

With his small build, dark features, nimble gait, bright eyes and saucy manner, Ronnie Stevens, who has died aged 81, was one of the busiest and most versatile character actors of his postwar generation. Whether in the last throes of West End revue, the heyday of subsidised touring classical companies, contemporary comedy, period musicals or traditional pantomime, he always looked in his element.Born in Peckham, south London, and educated at Peckham central school, he showed theatrical promise from the age of 12 in his personality and singing voice, notably as a crooner at Dulwich baths. Not that he was intended for the stage; when he won a scholarship to Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts, his parents expected him to become a commercial artist. But after four years’ service in the second world war, both in the RAF and the Royal Engineers, Stevens turned to his first love, the stage, and used his gratuity to train at Rada.

At 23, he landed a job in Peter Myers’ intimate revue, Ad Lib, at the tiny Chepstow Theatre Club, in Notting Hill, in 1948. Satirical revue was then in fashion, and for five years, in one London fringe show or another, he mocked well-known people, their manners and institutions. By today’s standards, it was insipid stuff, but the techniques of intimate revue – with its quick-change routines, variety of mood, timing and atmosphere – provided first-rate training.

Stevens reached the West End in 1953 joining such stalwarts as Cyril Ritchard, Diana Churchill and Ian Carmichael in Myers’ High Spirits (Hippodrome). A year later, virtually the same writing team came up with Intimacy at 8.30, at the Criterion, starring Joan Sims – with Stevens proving himself a good team member.

When the team came up with its third West End success, For Amusement Only (Apollo, 1956), Stevens showed himself a minor master of the genre, with its dependence on complicity between actors and audience. In such diverse 1960s shows as the Brechtian-type musical satire on modern youth, The Lily White Boys (with songs by Christopher Logue) at the Royal Court, or The Billy Barnes Review (Lyric, Hammersmith), he had numerous parts; and in that American musical, Rose Marie (Victoria Palace), he made a feature of the comedy role, Hard-Boiled Herman.

But although no one could put a finger on the reason – the song-and-dance ingredients of revue had reached television in That Was the Week That Was; and the four-man university show, Beyond the Fringe, was thriving without tunes or feminine charm – the writing was on the wall for traditional revue. Stevens’ last one reached the Savile in 1961 and felt old-fashioned. In a barn of a theatre, The Lord Chamberlain Regrets left most critics with regrets. The censor still had seven years of rule over the theatre, but the material lacked spite or wit.

Stevens had to turn legitimate. After Alan Ayckbourn’s early, frail experiment in mime humour, Mr Whatnot (Arts, 1964), in which he darted about in blazer and boater amid silent, stately home fun, he turned to Toby Robertson’s Prospect Theatre Company, set up to tour the classics – and prospered.

Whether it was an arch Sir Fopling Flutter in Etherege’s The Man of Mode (1965), a ruminant Feste in Twelfth Night (1968) or a nervous type in Feydeau’s The Birdwatcher, he was a valuable acquisition. In 1969 he moved for two seasons to the open-air theatre, Regent’s Park. Back with Prospect in 1971, he proved an affecting Fool to Timothy West’s King Lear (1971), which toured to the Edinburgh festival and Australia, before going to the West End (Aldwych, 1972). Later that year, he co-founded the Actors’ Company, a troupe designed to roam with the classics, headed (though wages and billing were impeccably egalitarian) by Ian McKellen.

Stevens’ credits included another Feydeau farce, Ruling the Roost, Ford’s tragedy ‘Tis Pity She’s a Whore, and the premiere of an Iris Murdoch play, Three Arrows, set in Japan. With Prospect, in 1973, he came into his own as Sparkish in The Country Wife, ending a global tour in the West End the following year as Gower in Pericles (Her Majesty’s).

At that time the regions showed more scope for a serious-minded actor than London. Hence Stevens’ move to Leeds Playhouse. After a stint at the Bristol Old Vic, he was back in north London, at St George’s Elizabethan Theatre – a converted church – in five or six Shakespeares in 1976 and 1977, and in 1978 back with Prospect at the Old Vic, the National Theatre having moved to the South Bank. This was the heyday of Stevens’ career as a classical actor.

Meanwhile, television beckoned increasingly. Apart from early appearances as the narrator in Oliver Postgate’s cartoon series, The Saga of Noggin the Nog, or as a teacher in AJ Wentworth, BA, and such programmes as Bresslaw and Friends, Stevens’ credits in the 1990s included guest appearances in Goodnight Sweetheart and As Time Goes By. He was also in many films from 1952. His wife, Ann Bristow, predeceased him; he is survived by their two sons.

· Ronnie Stevens, actor, born September 2 1925; died November 12 2006

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.