Anna Manahan was a very respected Irish actress who achieved major success on Broadway in her mature years. She was born in Waterford in 1924. She acted on stage with the famed Gate theatre in Dublin which was run by Hilton Edwards and Michael MacLiammoir. While on tour with them in Egypt in 1955 her husband became ill after swimming in the Nile and died. In 1957 she had success in Dublin in “The Rose Tattoo”. In 1969 she was on Broadway in Brian Frield’s “Lovers” and in 1998 she won a Tony for her performance in “The Beauty Queen of Leenane”. Her few films include “Clash of the Titans” in 1981, “Hear My Song” and “A Man of No Importance”. On television she won critical praise for her performances in “Me Mammy”, “The Irish R.M” as the housekeeper Mrs Cadogan and “Fair City”. She died in 2009 at the age of 84.

“Guardian” obituary:

Anna Manahan, who has died at the age of 84, enjoyed a career of almost 60 years as one of Ireland’s most distinguished actors, which also brought her before the British television audience from the 1960s to the 80s. A charming, even seductive, presence on stage or screen, she could be waspish and egotistical in private life, a characteristic that she was not concerned to conceal. Though she was generally quiet and reserved, her temper could flare up when occasion demanded, and she could be, as the leading Irish critic Fintan O’Toole said, “a proud and formidable rebel”.

Born in Waterford, in the south-east of Ireland, Manahan was an almost exact contemporary of Siobhán McKenna, but adroitly avoided comparison with her more celebrated compatriot. She studied under the legendary Ria Mooney alongside Milo O’Shea, Marie Keane and Jack MacGowran, and found her early success in the company of Hilton Edwards and Micheál MacLíammóir’s Dublin Gate theatre. Having married a fellow actor, Colm O’Kelly, she was touring in Egypt with the Gate in 1956 when O’Kelly, who was working as the stage manager, suddenly died. As MacLíammóir recorded in his diary, Manahan insisted on appearing that night: “The fact that she can contemplate [it] at all is a part of the stuff of which players are made.” There were no children and she never remarried.

Manahan was a totally professional actor, with three very distinctive qualities: she was faithful to the text; she was a formidable presence, with an emotional expressiveness to match; and she had the striking capacity to be quintessentially Irish without being “Oirish”.

O’Toole thought that Manahan learned her steeliness in the face of the 1957 attempt to ban the Dublin production of Tennessee Williams’s The Rose Tattoo, in which she excelled as Serafina. But MacLíammóir had noticed that her bereavement had already changed this “dark and buxom character actress, usually bashful and diffident”, into a strongly self-reliant personality. “She never played with greater absorption, with more truth, with slyer or wickeder humour,” he wrote of her performance on the night of O’Kelly’s death. “One can only bow one’s head before this sort of courage and this sort of grief.”

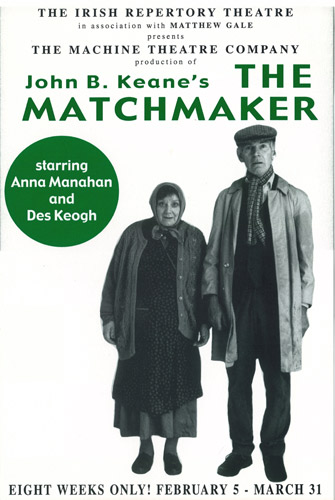

In 1958 Manahan created the role of Big Rachel in John Arden’s Live Like Pigs at the Royal Court theatre, and she remained both a “big” figure on stage (with John B Keane creating the lead in Big Maggie for her) and a familiar one in the West End, in Joe Orton’s Entertaining Mr Sloane and as June in Frank Marcus’s The Killing of Sister George.

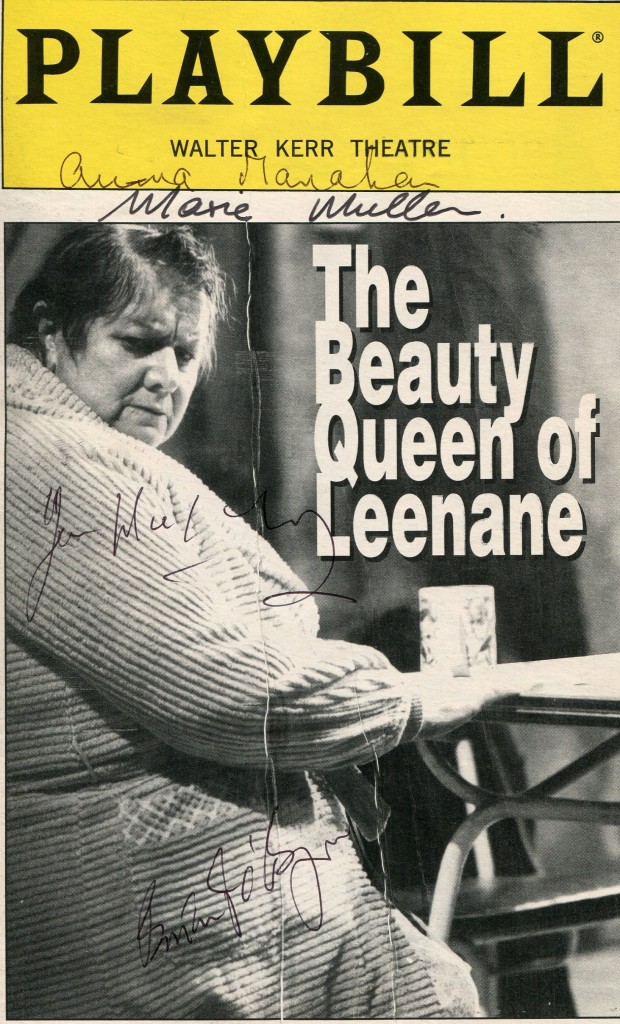

Nominated for a Tony award for best supporting actress in 1969 for her role in Brian Friel’s two-hander Lovers (with Niall Tóibín), she won the award 30 years later as Mags Folan in Martin McDonagh’s The Beauty Queen of Leenane. It was her return to Broadway as a grande dame of the stage after decades mainly on television, and demonstrated her capacity for bleakness and depravity, in contrast to her easygoing domesticated televisual presence.

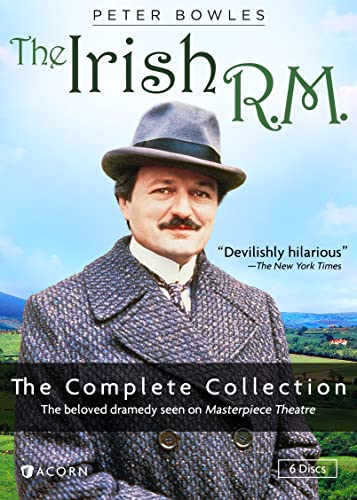

Nevertheless, TV came naturally to Manahan, first in the Irish rural soap opera The Riordans, followed by Hugh Leonard’s Me Mammy (1968-71) for the BBC, in which – though in reality only two years his senior – she played Milo O’Shea’s strongly Catholic mother. She took the title role in RTÉ’s sitcom Leave It to Mrs O’Brien in the 1980s and the cook, Mrs Cadogan (or O Cadagain), opposite the harassed Peter Bowles in the RTÉ-Channel 4 adaptation of Somerville and Ross’s The Irish RM. She returned to soap opera as Ursula in RTÉ’s urban serial Fair City in 2005.

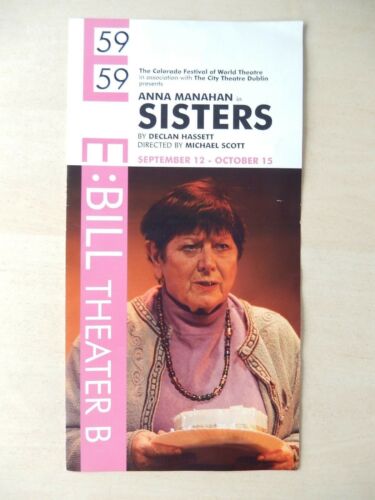

Manahan’s last stage role was in the 2005 production of the one-woman monologue Sisters, written for her by Declan Hassett. It toured Ireland and travelled to Colorado and Broadway.

When the Irish government announced in 2008 that healthcare entitlement to citizens over 70 would be restricted on budgetary grounds, Manahan made a noisy public protest, suggesting that the taoiseach and other leading politicians should be pilloried. As a result, she became first patron of Active Retirement Ireland.

She received the gold medal of the Eire Society of Boston in 1984, the freedom of her native city in 2002 and, in 2003, an honorary doctorate from the University of Limerick and the Woman of the Year drama award.

John Arden writes: I had never heard of Anna Manahan when Anthony Page, a director at the Royal Court, brought her over to London to play Big Rachel in my first play, Live Like Pigs, in 1958. Margaretta D’Arcy, already in the cast, had acted with her in Dublin, and assured me we would see something extraordinary. Indeed we did.

Anna played opposite Wilfred Lawson, who would cautiously and meticulously build up his part from some small prop or bit of business – he once spent a morning’s rehearsal playing little games with a bowler hat until he knew what he wanted to do with it, and thus what he needed to do with the entire scene – whereas Anna allowed the essential spirit of the role to burst from her like an uncoiled spring of rhetorical ecstasy. This contrast of style created a constant mutual irritation; the irritation created the contrast and conflict between the characters, till Rachel finally stalked off the stage, abandoning her ancient companion.

Margaretta D’Arcy writes: The last time I met Anna was in New York, where she was playing in The Beauty Queen of Leenane; she invited me to a memorial mass for the actor and singer Agnes Bernelle, a generous gift of remembrance for that other old warrior.

Anna was the last of a splendid breed of women warriors in Irish theatre – among them the actor-managers Nora Lever, Phyllis Ryan and Carolyn Swift – who all kept the flame alive in the bleak and famished 50s, working away on shoestrings, with little recognition and often some ridicule. They put theatre ahead of their personal lives, and had social consciences, too, which now and again leaped out like the furies. Anna’s passion did not remain within the confines of the proscenium.

I was involved with JM Synge’s The Tinker’s Wedding at the 37 theatre club in 1952, the first production of that play in Ireland: Anna, astride the cart, defying the priest, refusing to pay the marriage money, broadcast the same defiance only last year over the issue of medical cards for the over-70. s All hail, warrior queen!

• Anna Maria Manahan, actor, born 18 October 1924; died 8 March 2009.

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.

Dictionary of Irish Biography

Manahan, Anna (Maria) (1924–2009), actress, was born on 18 October 1924 in Waterford city, third child in a family of three sons and three daughters of Patrick Manahan (d. 1967) and Mary Manahan (née Barry). Her father was a clerk in the margarine manufacturing business of W. and C. McDonnell, and later the manager of a local ballroom, well known as a member of a theatrical family and as a comedian and singer in amateur and semi-professional opera and dramatic productions. His brother W. A. Manahan had a dance band popular in the south-east of Ireland in the 1920s and 1930s; Anna’s cousin Sheila Manahan (1924–88) was a stage and film actress in England.

Anna grew up in Lombard Street, Waterford, and was educated by the Mercy nuns, who encouraged her to perform in school plays. She joined Waterford Dramatic Society and, after leaving school, moved to Dublin to study in the celebrated Gaiety theatrical school run by Ria Mooney (qv). Contemporaries there included Milo O’Shea (qv), Eamonn Andrews (qv) and Marie Kean (qv), and she was to act with many of them throughout her later career. After only a few weeks in the school, Mooney suggested that Anna should gain experience with a touring fit-up company, Equity Productions. In 1946 a promised move to Hollywood and film appearances did not materialise when the talent scout’s company failed. Manahan went to London to look for roles there, with limited success, but in 1949 came home to be with her eldest sister Ellen, known as Billie, who died in May that year. Anna then had a season in Limerick with the 37 Theatre Company; she was spotted as a promising young actress by the directors Hilton Edwards (qv) and Michéal MacLiammóir (qv), and spent seven years in their Dublin Gate Theatre company.

A colleague, Colm O’Kelly (brother of Kevin O’Kelly (qv)), an actor in the 37 Theatre Company and stage manager with Edwards and MacLiammóir, helped her through anxiety attacks and depression after her sister’s death, and they married in Waterford cathedral on 14 June 1955. The Munster Express of 17 June 1955 headlined the ‘happy ending to the romance of the Irish stage’, but the happy ending was to elude the young couple. They travelled with the Gate Theatre on a tour of Egypt in 1956; Colm O’Kelly contracted polio, probably after swimming in the river Nile, and died after only a few hours in hospital, on the morning of 10 April 1956. True to theatrical tradition, Anna Manahan took her place on stage that same night, playing in a comedy, but after her husband’s funeral in Alexandria, travelled home on her own. In later years she had several important relationships, but never remarried. Acting helped her to cope with her personal loss, which in turn allowed her to draw on depths of emotion and understanding to perform a range of classic roles.

She became a household name in 1957 after her first starring role, in the first Dublin Theatre Festival. She appeared in the tiny Pike Theatre, Dublin, in Tennessee Williams’s notorious play ‘The rose tattoo’, directed by Alan Simpson (qv). The first reviews were very favourable, but the play ran into serious difficulties when someone who had presumably been a member of the audience reported to the Gardaí that Manahan’s character, Serafina, dropped a condom on the stage. In fact, the action was merely mimed, there was no condom; but at a time when stage censorship regulations reflected the catholic church’s attitudes to obscenity and to contraceptive devices, the authorities responded quickly by arresting the director. The resultant controversy was one of several episodes in a continuing struggle over censorship, between the avant-garde, abetted by well-known troublemakers like Brendan Behan (qv), and the conservative elements in Irish society; though Simpson was acquitted, after a year of misery, the theatre was forced to close because of his financial difficulties.

Manahan’s career seldom faltered thereafter, and she was internationally known for her appearances in scores of successful shows. Her physical presence and earthy strength impressed directors and audiences in various theatres from the 1950s up to her last stage appearance in ‘Sisters’ (2005); she worked in the Gate in Dublin, in the National Theatre and others in London, and on Broadway and in theatre festivals around the world. She created the role of Big Rachel in ‘Live like pigs’ (1958) by John Arden (qv) in London, and John B. Keane (qv) wrote the play ‘Big Maggie’ (1969) with Manahan in mind to play the leading eponymous character. In 1969 Manahan was nominated for the Tony award, for best supporting actress, in a Broadway production of ‘Lovers’ by Brian Friel. Almost thirty years later, in 1998, in a very different role, she won a Tony award for her appearance as ‘featured actress’ in the part of Mag Folan, the repellent, slovenly, scheming mother, in ‘The beauty queen of Leenane’, by Martin McDonagh. The play toured Ireland, transferred to London, and ran for eighteen months on Broadway.

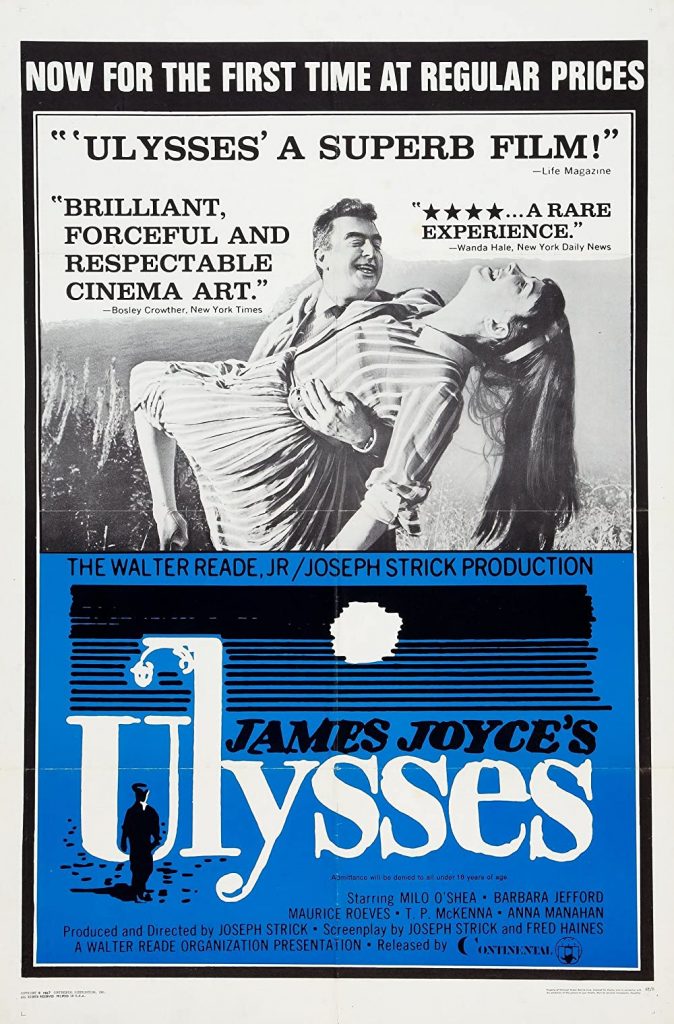

Irish and British audiences might not have expected Manahan to perform with quite such power and viciousness as she showed in Mag Folan; for years before her appearance in McDonagh’s play, Manahan had been somewhat typecast in more comic roles, particularly on television. She became familiar to a wide viewing public as Milo O’Shea’s ‘Irish mammy’ in Me mammy (BBC, 1968–71), written by Hugh Leonard (qv); as the cook Mrs Cadogan in the RTÉ/Channel 4 series The Irish RM (1983–5); and in RTÉ dramas and soap operas, including The Riordans and Fair city (playing Ursula, 2004–9). She also appeared in radio dramas, television films and in a few films for the big screen. Her first film, She didn’t say no! (1958), was about a woman (not her character) with six illegitimate children by different men (unsurprisingly, the film was banned in Ireland). She also played Bella Cohen in a film version of Ulysses (1967) and appeared in Black day at Blackrock(2001; written and directed by Gerry Stembridge).

In later life Manahan returned to Waterford and lived with two of her brothers. As a way of giving something back to the life of the theatre which had sustained her since her own childhood, she gladly participated for years as a judge in amateur dramatic festivals round the country. A different kind of celebrity came to her in 2008 when she spoke out vehemently against cuts in health care which would affect old people; her widely reported contribution to the controversy greatly helped the campaign to have medical cards restored to some older people. Even before her being selected as celebrity patron of Active Retirement Ireland in 2008, Manahan’s views had already had an impact on attitudes to older people. In 2004, speaking in the Waterford Area Partnership’s ‘age and power’ conference, she had suggested the establishment of a Golden Years Festival in Waterford to celebrate the achievements of older people and encourage creativity and participation in society. It was successfully set up and marked ten years of existence in 2014.

In 2002 Waterford showed appreciation of one of its most famous natives by making Anna Manahan a freeman of the city, and she was posthumously included in a permanent exhibition of ‘Waterford treasures’ in the Bishop’s Palace. Manahan also won the gold medal of the Eire Society of Boston in 1984, and in 2003 received an honorary doctorate in letters from the University of Limerick. She was the subject of a documentary, All about Anna, screened by RTÉ in 2005.

After a long illness she died in Waterford on 8 March 2009, and was buried in Ballygunner cemetery