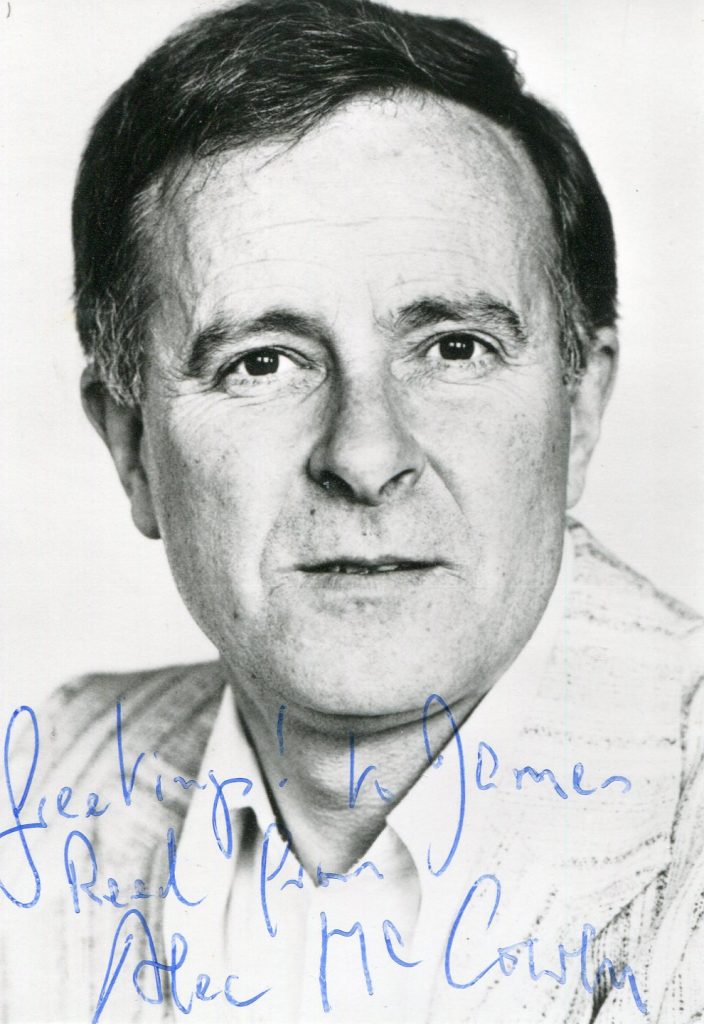

Alec McCowen obituary in “The Guardian” in 2017.

Alec McCowen who has died aged 91, was an actor of dazzling technical brilliance whose career encompassed the classics, new plays, two remarkable one-man shows and an abundance of TV and film, including lead roles in 1972 in Alfred Hitchcock’s Frenzy and George Cukor’s Travels With My Aunt. “I have always wanted to be an entertainer rather than an actor,” McCowen once wrote, but the truth is he was both: he could immerse himself in a character but also hold an audience spellbound, as in his celebrated one-man performance of St Mark’s Gospel.

I got to know McCowen in his later years and he proved a wonderful raconteur. He delighted in telling a story about going to New York in the 1950s to appear in The Matchmaker, discovering he was debarred by American Equity rules and, moodily unemployed, finding himself one day sharing a backstage sofa with a highly intelligent woman who shyly revealed she too was an actor: her name was Marilyn Monroe. On a more caustic note, he claimed that Peter Brook, who directed him as the Fool in King Lear at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1962, said to him just before curtain-up on the first night, “You’re nine-tenths there.” Not, said McCowen, the most helpful thing to tell an actor about to go on.

He was born in Tunbridge Wells, Kent, and gave a vivid account of his early years in his book Young Gemini (1979). His father, Duncan, whom he grew to adore, was a pram-shop owner and natural exhibitionist with a rare capacity to fart God Save the King at the dinner table. Even in the Kentish bourgeoisie, the strain of performance seemed to run in the family: McCowen’s mother, Mary (nee Walkden), was a teenage soubrette and his paternal grandfather a Christian evangelist. Acting, however, was still regarded with suspicion and McCowen, although a passionate cinema-goer, learned to disguise his ambition by posing as an average schoolboy at the Skinners’ school.

In 1941 he broke free by gaining a place at Rada in London. After a summer vacation appearance in Paddy the Next Best Thing in Macclesfield, he cut short his studies and over the next few years combined appearances in weekly rep with tours to India and Burma as well as a season in Newfoundland. It was during the latter that he had a life-changing trip to New York, where, during the 1948 season, he saw Marlon Brando on stage in A Streetcar Named Desire. After the cold, efficient naturalism of London theatre, McCowen later wrote, “this acting was warm, rich and human and had a depth and subtlety I had never seen before”.

Newly energised, McCowen returned to London, where he made his West End debut in 1950 and built up an enviable portfolio. I first became aware of him at the Old Vic in 1960 where he played Mercutio in Franco Zeffirelli’s production of Romeo and Juliet. I have never forgotten his electrifying death, where, joking to the last and blithely unaware that he has received a mortal thrust, he suddenly slid down the side of a pillar.

He was equally remarkable as the Fool in Brook’s 1962 King Lear, sitting on a bench alongside Paul Scofield, in the title role, as if anxiously gauging how close the king was to madness. He accompanied this with a pin-sharp performance as the Antipholus of Syracuse in the same year in The Comedy of Errors, Ian Richardson his twin, and earned even more acclaim at Hampstead Theatre in John Bowen’s dystopian drama After the Rain (1966).

In that McCowen played a bespectacled fanatic who believes he is God. Oddly enough, in his next play, Hadrian the Seventh (1967), he played a similar hermetic fantasist who imagines he is pope. It was this performance, first at Birmingham Rep and then, for two years, at the Mermaid, that turned McCowen from an admired actor into a star. What he caught brilliantly was the way the hero leapfrogged from indigent obscurity to the chair of St Peter, and one particular image of McCowen, raffishly smoking a cigarette while papally enthroned, is enshrined in the memory. The play won him the first of many Evening Standard awards and was in 1969 as big a hit on Broadway as in London.Advertisement

After that, all doors opened for McCowen. In 1970 he appeared in Christopher Hampton’s hit play The Philanthropist, which moved from the Royal Court to the West End and Broadway and in which he memorably declared: “My trouble is that I am a man of no convictions – at least I think I am.”

Having played Hampton’s compulsively amiable hero, McCowen then appeared as Alceste in Tony Harrison’s version of Molière’s The Misanthrope for the National Theatre in 1973. He was partnered in that by Diana Rigg and, after McCowen had created the role of the psychiatrist Dysart in Peter Shaffer’s Equus, the two made an equally dazzling team in John Dexter’s West End revival of Pygmalion the following year: McCowen’s Higgins was a brilliant study of a testy, childlike neurotic exultantly crying that “making life means making trouble”.

McCowen’s career, however, took a new turn in 1978 when he devised and directed his own solo performance of St Mark’s Gospel, in which the narrative was vigorously enacted. The idea came about at the suggestion of his sister, Jean, who was a vicar’s wife.

I saw its first performance at the Riverside Studios, Hammersmith, and was bowled over by it: I wrote at the time that “McCowen related the familiar story with all the precision, irony, intelligence and faintly controlled anger that characterises all his work” and that it was a superb piece of acting. It went on to do long runs at the Mermaid and Comedy theatres in the West End before transferring to Broadway.

In 1984, again at the Mermaid and, later, on Broadway and on Channel 4, McCowen went on to do a no less remarkable one-man show, written by Brian Clark, about Rudyard Kipling that decisively proved the writer was much more than the imperialist propagandist of popular imagination.

In later years, McCowen went on to give any number of fine performances. In 1986, the year he was appointed CBE, he was a sprightly Sir Henry Harcourt Reilly in TS Eliot’s The Cocktail Party; in 1990 the mysterious Uncle Jack, a Catholic missionary who has gone native in Uganda, in Brian Friel’s Dancing at Lughnasa; and in the RSC’s Tempest at Stratford in 1993 a superbly domineering Prospero who reacted with horror when Simon Russell Beale’s newly liberated Ariel spat in his face.

In addition to his many stage roles, McCowen appeared in more than 30 films, starting with The Cruel Sea in 1953. His most famous role, however, was in Frenzy, as the assiduous sleuth whose features crumple into dismay at his wife’s reckless experiments with haute cuisine.

As well as bringing finesse and passion to acting, McCowen directed plays by Martin Crimp and Terence Rattigan at the Orange Tree and Hampstead, and was an excellent writer (a second volume of memoirs, Double Bill, appeared in 1980) and the most exhilarating company. He loved especially to reminisce about great entertainers, of whom the American comedian Jack Benny was his favourite. In a long and distinguished career, McCowen could be said to have graced acting with the verbal precision and immaculate timing that were Benny’s comic trademark.

McCowen’s partner, the actor Geoffrey Burridge, died in 1987.

He is survived by Jean, two nephews and two nieces.

• Alexander Duncan McCowen, actor and director, born 26 May 1925; died 6 February 2017