The Guardian Obituary in 2011

Anne Francis, who has died of complications of pancreatic cancer aged 80, is now best remembered mainly due to the lyrics “Anne Francis stars in Forbidden Planet \ Oh-oh at the late night, double-feature, picture show”, which were sung over the opening credits of The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975), and for the cult science-fiction movie to which they refer, Forbidden Planet (1956). The only woman in the cast of Forbidden Planet, Francis had a sprightly charm and a wide-eyed child-like innocence as Altaira, the space-age Miranda in the transposition of Shakespeare’s The Tempest to a distant planet.

The mini-skirted teenaged daughter of the exiled Dr Morbius (Walter Pidgeon) has never seen any man except her father until a group of US astronauts, led by Commander John J Adams (Leslie Nielsen), arrive. While never exactly exclaiming “O brave new world that has such people in it!”, she expresses it with her eyes and is quite curious and happy to learn about man-woman relationships, and the art of kissing, from the new arrivals. Warned by her father to avoid contact with the earthmen, she beams up Robby the Robot (Ariel). “Robby, I must have a new dress, right away,” she tells the android. “Again?” he responds. “Oh, but this one must be different! Absolutely nothing must show – below, above or through.” “Radiation-proof?” “No, just eye-proof will do‘.

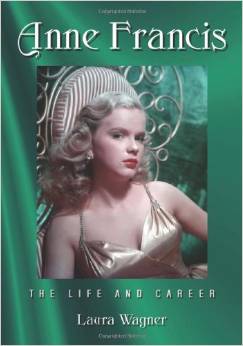

The curvaceous, blonde, 5ft 8in Francis, with a becoming little mole next to her mouth, was never eye-proof, especially during the films of the 1950s that launched her career proper and sealed her fame. Born in Ossining, New York, she came to public notice in her childhood. “I didn’t come from a show-business family; neither of my parents were involved in it,” she said in 1997. “Actually, someone said to my mom that they thought I’d make a good child model, so she took me up to the John Robert Powers modelling agency, which was the top one in New York City at that time. We were sitting in the outer office with a lot of other folks and Mr Powers himself came out of his office door, looked around the corner, pointed at me, and said, ‘I’ll take that one!’ And that’s how it all started, when I was just six years old.”

She started performing on children’s radio and then moved on to Broadway, aged 11. Billed as Anne Bracken, she played alongside Gertrude Lawrence and Danny Kaye in the Kurt Weill musical Lady in the Dark (1941). There followed several radio soap operas before she signed a one-year contract with MGM. However, the studio only gave her bit parts in three films. It was not until 1950 that she was given her first chance to act on screen, in the United Artists production So Young, So Bad. Although the latter half of the title was also applicable to the latter half of this tale of delinquent girls in an authoritarian reform school, Francis was excellent as an abused teenage mother, lusting after the humane doctor (Paul Henreid).

The role brought her to the attention of the studio boss Darryl F Zanuck, who signed Francis to a 20th Century-Fox contract. Among the five films she made for Fox were two lightweight pictures in which she played the daughter of prissy Clifton Webb, Elopement (1951) and Dreamboat (1952), before being allowed more maturity and period dress as a landowner in 19th-century Haiti in the title role of Lydia Bailey (1952).

But it was on her return to MGM that she co-starred in a range of good movies with a range of good parts, belying her reputation, derived from Forbidden Planet, of an innocent, doll-like performer. In Rogue Cop (1954), she plays the drunken discarded moll of a gangster (George Raft). In John Sturges’s superb Bad Day at Black Rock (1955) – where she was, as in Forbidden Planet, the only woman in the cast – she takes the role of a seemingly tough garage owner in jeans, who doesn’t want to help John J Macreedy (Spencer Tracy) discover the secret of her town where “somethin’ kind of bad happened”, and who meets a tragic end.

Francis was also involved in the then sensational, now dated, juvenile delinquent school drama, Blackboard Jungle (1955). She played the pregnant wife of a dedicated teacher (Glenn Ford), who is the victim of threatening notes and phone calls from a depraved student. It was a strong performance among many, though the film is best remembered for being the first with a rock’n’roll soundtrack, by Bill Haley and the Comets. She was even more impressive as Paul Newman’s war-widow sister-in-law in The Rack (1956), and in The Hired Gun (1957), she is sentenced to hang – unusually, for a woman in a western – for the murder of her husband.

It was not long, however, before she “disappeared” for many years into television, only to emerge spasmodically on to the big screen to remind audiences that she was still around. “I had reached the end of my rope as a contract player at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. They were always looking for a new face, so I thought, forget it, I want to go back and do television. In those days, that was the death knell for an actor. You worked television, you didn’t do film. Of course, they cross over all the time today.”

Among the films in which she starred was Girl of the Night (1960), a bold (for the time) and gritty film noir in which she portrayed a high-priced prostitute, exploited by her madam and pimp, until she finds help in psychotherapy. “It is the one film I’m most proud of,” Francis stated. “I was going through analysis at the same time and I was playing going through analysis on that film. It was quite a workout, and it really beat me up.”

Francis had her own TV series, Honey West (1965-66), in which she shone as a sexy and liberated detective, aided by John Ericson (who had played her weak brother in Bad Day at Black Rock). The role won her a Golden Globe and she was also nominated for an Emmy. For the next three decades there followed scores of television guest spots, including four episodes of Dallas in the early 1980s.

In 1982, Francis wrote a book entitled Voices from Home: An Inner Journey, which was about her belief in mysticism and psychic phenomena. In 2007, she was diagnosed with lung cancer, and immediately underwent chemotherapy and had surgery to remove part of her right lung. Francis, who was married and divorced twice, is survived by two daughters, Maggie and Jane.

Time Magazine Tribute to Anne Francis in 2011.

The poster artwork for Forbidden Planet — MGM’s 1956 reworking of Shakespeare’s The Tempest into a science-fiction parable of ego vs. id — showed a fearsome cyborg holding a sleeping blond in a diaphanous gown that highlighted her gaudy curves. The blond was Anne Francis, the machine was Robby the Robot, and the poster had nothing to do with the movie: Robby was a gentleman scholar among automatons, a protector of Francis’s character Altaira, not a menace to her. But that image may be the one that sprang to the minds of moviegoers this week, when the actress’s death was announced. Francis died Sunday, Jan. 2, of pancreatic cancer at a rest home in Santa Barbara, Calif. She was 80.

A lifelong trouper in radio, TV, theater and films, Francis is best known for a flurry of mid-’50s MGM features, for a couple of indelible episodes of The Twilight Zone and for her one-season TV sleuth series Honey West in 1965-66. In her admirers’ memories, she conjures up a description that her co-star William Lundigan enunciated in their 1951 comedy Elopement: “Tall, blond, willowy, sort of ripples when she walks… She’s got those Minnie Mouse eyes, turns ’em on you like a pair of headlights. Her voice is soft and husky — kind of makes you feel as though your back is being scratched.

It happens that Lundigan is talking about another woman, but the attributes fit Francis, who was only 20 during the Elopement shoot. She was tall (5ft.-8in.), a seemingly natural blond, with large, lasering blue eyes and an expressive alto voice. Francis also had a forehead so high and smooth that she could have been one of the Metalunans from another ’50s space epic, This Island Earth. The actress’s signature feature — a mole just to the right of her lips — was so distinctive, it was written into the Elopement script. “What’s that?” asks her groom-to-be Lundigan. “It’s a mole,” she replies. “I was born with it. Don’t you like it?” He smiles and whispers, “I like everything you were born with.”

She was born Sept. 16, 1930, with that mole and a work ethic that never quit. The daughter of Philip Marvak, a businessman, and his wife Edith, Anne was a photographer’s model by her fifth birthday. (Pictures from the breadth of her career can be seen on annefrancis.net, the website she maintained until shortly before her death.) She was on television when it was just a gadget, appearing in CBS-TV’s first color tests before World War II. At 10 or 11 she was on Broadway with Gertrude Lawrence in Lady in the Dark and spent her teens in countless radio soaps, including Portia Faces Life and When a Girl Marries, where her child’s voice matured into its permanent, woman timbre. In 1948, when she was 17, she got bit roles in the MGM musical Summer Holiday and David O. Selznick’s Portrait of Jennie. She was back in New York, working on TV’s proto-thriller series Suspense in 1949, when Hollywood casting directors noticed that this reliable young actress was also a knockout.

There’s no doubting Francis’s worthiness as a pinup. Yet what came across, in her two-decade movie and TV prime, was not sultry ostentation but a preternatural poise and a questioning intelligence. Her beauty cloaked her brains without obscuring them. In one sense, she was a blend of Hollywood’s two most popular female types in the ’50s: the bombshell blonds Monroe and Mansfield — an adolescent’s notion of squeaky-voiced sexuality — and smart, slim vixens like Audrey Hepburn and Grace Kelly. You’d think someone would have seen Francis as the golden mean between these extremes, yet the studios that employed her (Fox from 1951 to 1954, then MGM for the next three years) had trouble deciding what to do with her.

Their frequent solution: cast her as a gorgeous bookworm, whose closest relationships are with father figures. That prim, stern comedy star Clifton Webb played her doting dad in two films: Elopement, with Francis as a prodigy of architectural design, and Dreamboat (1952), where her character is a literary scholar in horn-rimmed glasses and a trim gabardine suit; she’s writing her college thesis on the contention that Homer was not the sole author of The Iliad and The Odyssey because “No one man could write so much trash.” In Forbidden Planet she is the science-loving daughter of the planet’s only adult human, Walter Pidgeon; and in The Rack she is Pidgeon’s daughter-in-law, trying to help young Paul Newman through a wartime charge of aiding the enemy. In these roles, her hair was always pulled back, in an implicit dare for any man to let it down and unleash the beast. That was the goal of Francis’s young male co-stars: the thawing of an ice goddess.

The women Francis played usually saw men as curious subjects for further research. She treats her first kiss with Jeffrey Hunter in Dreamboat as an alien-earthling encounter, peculiar but pleasing. In her best-known role as Altaira, isolated on the Forbidden Planet after catastrophes have wiped out her mother and the rest of the colony, has grown up with only her father and a deer and a tiger she treats a pets. When she spots her first male humans — astronauts from Earth — she says, “I so terribly wanted to meet a young man, and now three of them at once!” When she invites spaceship commander Leslie Nielsen to join her for a swim in the pool, he notes regretfully that he didn’t bring his bathing suit. “What’s a bathing suit?,” she asks. Teetering toward camp, the movie is played seriously by the whole cast. And no one had a tougher challenge than Francis, since she’s wearing either various forms of a 23rd-century cheerleader tunic, or nothing.

In these busy years she played opposite some of Old and New Hollywood’s top leading men: Newman, Dick Powell in Susan Slept Here (as a vamp who morphs into a spider-woman during the film’s comic ballet sequence), Spencer Tracy in Bad Day at Bad Rock (as the only woman in a threatening town) and Glenn Ford in The Blackboard Jungle (as Ford’s ailing, pregnant, jealous wife). She appeared with Ford again in the 1957 Navy comedy Don’t Go Near the Water, with Earl Holliman stealing her from wolf-man Jeff Richards, just as Nielsen had from Warren Stevens in Forbidden Planet. That comedy, which demoted her to second female lead, ended her MGM contract and, oddly, cued a three-year absence from major film and TV work when Francis was still in her 20s — and at the presumed peak of her appeal.

Movies were increasingly a man’s preserve; women who wanted meaty roles often went into TV drama, where the pay was less and the shooting schedules brisk but the rewards of fully imagined and realized characters greater. In his first season of The Twilight Zone, Rod Serling gave her one such juicy part in the episode “The After Hours.” She played Marsha White, a young woman shopping in a department store for a gift, a golden thimble, for her mother. But an elevator operator takes her to the store’s ninth floor, deserted except for an insulting sales girl and, in the showcases, just one object: her thimble. Locked in overnight, she comes to realize her strange destiny. A gloss on the Philip K. Dick theme of the android who dreams he’s human, “The After Hours” focuses every scene on Francis, monitoring her face for clues, as bafflement escalates into rage and then settles into acceptance. It’s a splendid use of Francis’s persona: at once friendly and doll-like, human and otherworldly.

In 1960 she took the starring role in Girl in the Night, an indie-style drama about a lonely call girl misused by her madam (Kay Medford). Francis thought this was her best film work, and the film is remembered warmly but fuzzily; it is not available on DVD. She did lots more TV, including her second Twilight Zone: the ultra-weird “Jess-Belle,” Earl Hamner, Jr.’s folk-horror tale about a mountain girl so desperate for another woman’s man that she makes a pact with a witch and turns into a leopard. That was 1963, and two years later Francis got a shot at starring in her own TV action drama, Honey West.

The first hour-long series named for its female character, Honey West was based on Skip and Gloria Fickling’s pulp-novel series about a woman who took over her late father’s detective business. Mixing clichés from private-eye and international espionage stories, then flipping the gender, Honey was a Bond babe — Jane Bond — put in charge of the franchise, and comfortable with the power it gave her. She bested bad men with her karate skills, navigated hairpin turns on high-speed chases in her top-down sports car and, just as important, displayed the business-running executive skills only men of the era were supposed to possess. Honey had a hunky male assistant, Sam Bolt (John Ericson), but he was there mainly as eye candy for the women in the audience. The men had Francis’ efficient allure, her newly fluffy blond hair and, of course, her facial mole, which was featured so prominently in the opening-credit sequence you’d think it was the co-star.

Aaron Spelling, the show’s executive producer, was no militant feminist; 11 years later he would multiply Honey by three, give this trio the sort of patriarchal boss Honey never needed, and call it Charlie’s Angels. As the overseer of Honey West, Spelling made sure sensuality took precedence over suspense. A smarty-pants sex object, Honey wore earrings she could toss like darts to emit tear gas. She often sported tights that looked as if they’d been borrowed from Diana Rigg in The Avengers. Once she went undercover in a showgirl outfit with tiger stripes, which was appropriate for this feral beauty, since her character also kept a pet ocelot named Bruce (a cousin to Francis’s tiger playmate in Forbidden Planet and to the leopard she morphed into on (The Twilight Zone). All this animal attraction should have kept the show running for years, but it was canceled after one 30-episode season.

Truth to tell, that was about it for the iconic phase of Anne Francis’s celebrity. She was 35 when Honey West went south, and the actress who entered show business as a child would keep working for another 35 years. In the 1968 musical Funny Girl she was billed a generous fourth but virtually invisible, except when Barbra Streisand disses her at the start of the first act’s climactic (and climatic) number “Don’t Rain on My Parade.” Thereafter, Francis had no big roles in big movies, instead becoming one of those aging performers of medium wattage who stay employed by joining the perennial bus-and-truck company of TV series guest stars. Webb, as her stuffy father in Dreamboat, had sneered at television as a phenomenon that “encourages people who dwell under the same roof to ignore each other completely.” But for Francis it was a meal ticket that she cashed in for 60 years, from those early color tests in 1940 until her retirement in 2000.

In her post-Honey decades, Francis guested on a few comedy series — The Drew Carey Show and, as Bea Arthur’s college roommate, on The Golden Girls — but concentrated on the hour-long dramas. She graced The Fugitive, Mission: Impossible, Gunsmoke, Columbo, Kung Fu, Barnaby Jones, Police Woman, Dallas (in a recurring role), Jake and the Fat Man, Murder, She Wrote and such Spelling confections as S.W.A.T., The Love Boat, Vega$, Fantasy Island (four times) and, it’s only fair, Charlie’s Angels. All in all, in the second half of her career, she racked up credits in more than 100 films and TV shows. Could that be a record for most series as a guest star? Hard to say, but the gal kept gamely at her craft.

She married twice, both times for three years: at 21 to director Bamlett Price, Jr., and at 29 to Dr. Robert Abeloff; they had a daughter, Jane. After the dissolution of her second marriage in 1964, Francis was on her own. In 1970, she became the first single woman in California to be allowed to adopt a child — a girl named Maggie. Francis wrote a self-help book in 1982 and lent her support to many charities, including Direct Relief, which sends medical supplies to victims of civil unrest, and Angel View, for the physically challenged. She promoted these causes on annefrancis.net, which currently carries this message from 2009: “Dear Friends, Due to health issues, I’m unable to process my fan mail in a timely manner…. For those of you who’ve previously sent me fan mail and autograph requests, I’ll try to process them when I am able to do so.”

Even though she had retired 10 years earlier, survived lung cancer in 2004, and was ailing from the pancreatic cancer that finally felled her, the brainy, beautiful blond from the Forbidden Planet never stopped working, never ceased doing what she did best: being Anne Francis.