David Manners obituary in “The Independent” in 1998.

David Manners was born in 1900 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. He was a very popular Hollywood leading man of the 1930’s and starred opposite some of the great leading ladies including Katherine Hepburn, Loretta Young and Myrna Loy. His movies include “Journey’s End”, “Roman Scandals”, “Dracula” in 1931 and “A Bill of Divorcement”. He died at the age of 98 in 1998.

David Manner’s “Independent” obituary by Tom Vallance: DAPPER AND handsome, David Manners was a serviceable leading man whose screen career was confined entirely to the Thirties, during which he was in great demand. He made 37 films between 1930 and 1936, and played romantic lead to such stars as Barbara Stanwyck, Katharine Hepburn, Kay Francis and Constance Bennett.Though he was excellent as the hero-worshipping young officer in Journey’s End and the blind man who falls in love with a faith-healer in The Miracle Woman, it is for his roles in three classic horror films – Dracula with Bela Lugosi, The Mummy with Boris Karloff, and The Black Cat with both Lugosi and Karloff – that he is best remembered, and a few years ago he commented on the interest being shown in him by movie magazines and historians, “Most of today’s fans are 14-year-old worshippers of the horror films – my only claim to movie fame.”

Claiming descent from William the Conqueror, Manners was born Rauff de Ryther Duan Acklom in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1902 (some sources state 1900 or 1905). The family tree of his mother, Lilian Manners, included Lady Diana Cooper and the Duke of Rutland, while the Ackloms included the writers Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, W.H. Homing and Morley Aklom – Manners himself would take up writing later in his career.

He was educated at Collegiate Grammar School in Windsor, Ontario, and earned a degree in forestry at the University of Toronto, where he also studied acting under Bertram Forsyth, who ran the Hart House Theatre, where Manners made his stage debut in the title role of Euripides’ Hippolytus. After graduation, his jobs included foreman of a lumber camp in Canada and salesman in a London antique shop. When his parents moved to the United States, Manners decided to try his luck in the New York theatre.

In 1924 he joined Basil Sydney’s touring company; his roles included Bezano the bareback rider in He Who Gets Slapped and Solveig’s father in Peer Gynt. He made his Broadway debut in Dancing Mothers (1924), a comedy starring Helen Hayes. The production’s stage manager was George Cukor, who years later would direct Manners in the film A Bill of Divorcement (1932).

The actor’s first film role was a prestigious one. James Whale had directed both the London and New York productions of R.C. Sherriff’s powerful anti- war play Journey’s End, and was signed to direct the film version in 1930. He was having difficulty casting the pivotal role of the young Second Lieutenant Raleigh who irritates the seasoned Captain with his optimism and loyalty, and was thinking of sending to England for Maurice Evans when he was introduced to Manners, who successfully tested for the role.

With his clean-cut looks and perfect diction, Manners was quickly offered more roles, and starred opposite the former silent star Alice Joyce in He Knew Women (1930), Alice White in Sweet Mama (1930) and Loretta Young in Kismet (1930), in which he effectively played the young Caliph in love with a beggar’s daughter. He was vamped by Myrna Loy in The Truth About Youth (1930) and in The Right to Love (1931) was Ruth Chatterton’s secret lover.

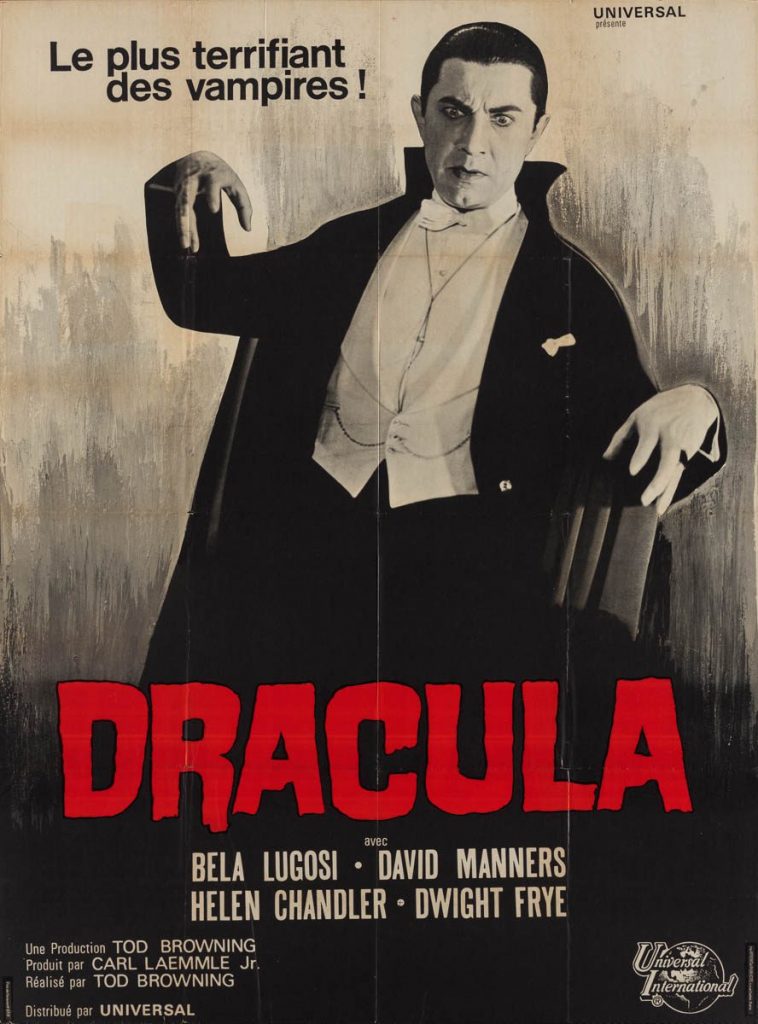

The role of John Harker, the nominal lead in Dracula (1931), was offered to Manners after several actors, including Lew Ayres, had turned it down. During script revisions, the role of Renfield, the estate agent who is vampirised, had been built up leaving Harker little more than a worried bystander, but Manners was given a higher salary than the rest of the cast and the film was an enormous success. Manners was to work with Lugosi twice more, and later commented that he found him “a pain in the ass from start to finish. He would pace around the sound-stage between scenes, velvet cape wrapped around him, posing in front of a full-length mirror while he intoned with sepulchral emphasis, `I am Dracula . . . I am Dracula!’ ” Asked about the film’s director Tod Browning, Manners said, “The only directing I saw was done by Kurt Freund, the cinematographer.”

Manners gave one of his most sensitive performances as a burnt-out flying ace in William Dieterle’s underrated The Last Flight (1931) and was fine as the shy blind man who conveys his love for Barbara Stanwyck through a ventriloquist’s dummy in Frank Capra’s The Miracle Woman (1931), though the film was banned in the UK. George Cukor cast him as Katharine Hepburn’s fiance, rejected by her after she discovers there is insanity in her family, in A Bill of Divorcement (1932), and Manners was to remain part of Cukor’s circle of close friends until the director’s death in 1983.

He was not too effective as the romantic lead in The Mummy (1932), a superior horror film dominated by Karloff, but was praised for his lively performance in The Warrior’s Husband (1933), which he followed with the role of the centurion in the musical Roman Scandals (1933).

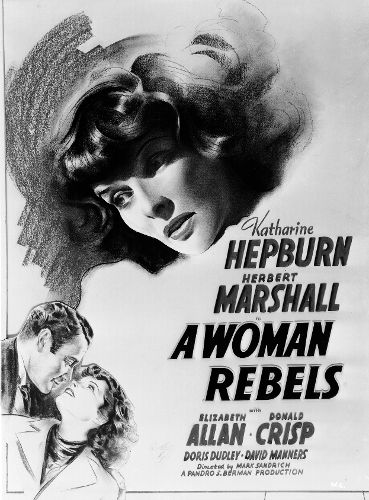

In The Black Cat (1934), considered the finest film of the director Edgar Ulmer, Manners and Jacqueline Wells were newly weds caught in a storm and taking shelter in the gloomy castle of Karloff and Lugosi. Though the film owes little to the Poe original, it is made with subtle expressionism and a dream-like atmosphere that is hauntingly effective. Manners played the title role in The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1935), strangled by Claude Rains on Christmas Eve, and appeared with Katharine Hepburn again in A Woman Rebels (1936), after which he retired from acting to concentrate on writing.

He was coaxed back to the theatre 10 years later, starring in Maxwell Anderson’s play Truckline Cafe. Directed by Elia Kazan and featuring an unknown Marlon Brando, the play ran for 13 performances on Broadway. But in December 1946 Manners scored a great personal success when he took over from Henry Daniell as Lord Windermere in Lady Windermere’s Fan. Designed by Cecil Beaton, the play was a hit in New York and toured for a year, after which Manners announced his permanent retirement as an actor.

David Manners had a home in Pacific Palisades, which he shared with a fellow writer, William Mercer, and ran an art gallery. Among his published books were two novels, Convenient Season and Under Running Laughter, and two philosophical works, Look Through and The Soundless Voice, the latter described by one critic as “a penetrating book on meditation”.

In recent years, rich due to land investments, he lived alone in an ocean- view apartment in Santa Barbara. Married briefly early in his career, he was noted for maintaining a private personal life and refusing to dwell on the past, though he declared fond memories of his Hollywood friendships with Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, George Arliss, Constance Bennett and others. “Tried and true friendship,” he said, “that’s what this old world needs plenty of.”

Tom Vallance

Rauff de Ryther Duan Acklom (David Manners), actor: born Halifax, Nova Scotia 30 April 1902; married; died Santa Barbara, California 23 December 1998.

His “Independent” obituary can also be accessed here.

Comments

Greg Wilson

Hi Liam,

I knew David as a friend the last ten or so years of his life. When I knew him he didn’t like to talk about the movie days long behind him, “There’s a lot more to me than that”, and wondered why people kept sending him requests for autographs. One afternoon he showed a handwritten birthday greetings from Helen Hayes. She sent him a birthday greeting every year sent they met and worked together on stage. On another afternoon, David received a call from Katharine Hepburn. Sixty years later. “Oh my God!” David exclaimed. “David, are you alright? Do you need money?” “No, I don’t need any money,” said David. That was it. David lived in various senior retirement facilities when I knew him. One day on a drive, he pointed out his home up on a hill in Pacific Palisades, saying, “If remembering that is ego–so be it.” I laughed my head off. David was stoic. Occasionally he talked about his years in the desert after his acting years, 30 years I believe, and said it was the best time of his life. He built a house there, talked about the love of his life who lived with him, who he always lead me to believe was his wife. It wasn’t, David was homosexual, his great love was a man. I’m glad I knew nothing about David the 1930’s movie star, which might have artificially colored our friendship. Maybe not. I’d read his last couple books, it was from that basis that we became good friends; David, a great friend. I still have the many letters David wrote to me. Perhaps David did get rich when they sold the resort where he worked for 30 years to developers. He told me he didn’t own much of the property, a small share of it given to him by the owner. He said that if he’d known the property was being sold off to developers, he wouldn’t have voted to sell it. David’s home in Pacific Palisades was nice enough, but it wasn’t on the grand scale like a rich person might have. I met David as his next home in Santa Barbara, small ranch-style. He was sitting in the living room, told me to come in when I knocked on the door. He was dressed in a nice suit and dignified. The first thing he said was, ‘Tell me about yourself.” I told him some of the highlights as I remembered them. I didn’t ask about David’s background in return, didn’t care. David’s background was revealed by him in brief sentences here and there over the years. In one letter I still have, he talked about the movie business briefly, I guess I had finally asked him about it. He finished the account by writing, “I don’t know how this is going to help you at all.” He mentioned that he was the last in line of William The Conqueror. That didn’t mean anything to me, we are all last in line of someone. But the fact that he was last in line of William The Conqueror, must have meant something to David, perhaps a great deal, or he wouldn’t have mentioned it. David put a quarterly letter that went to some 150 people like myself. The letter was always four pages, typed out on a manual typewriter. The letter was about “Conscious Awareness,” what David had rediscovered, and what he said we all are. He put the letter in the envelopes himself, addressed them himself. One day I mailed him several books of stamps, typing paper, envelopes. He was ecstatic.

Liam

Thank you so much for your very interesting article on David Manners. He had a special screen presence.

Liam

Thanks for your lovely article on David Manners

Much appreciated.

Liam