Jon Whitleley was one of best of British child film actors. He was born in 1945 in Scotland. He came to national fame for his major role in the thriller “Hunted” with Dirk Bogarde in 1952. Jon died in May 2020.

The following year he gave another splendid performance in the gem “The Little Kidnappers”. In 1955 he went to Hollywood to make the Cornish smuggler tale “Moonfleet” directed by Fritz Lang and also starring Stewart Granger and Joan Greenwood.

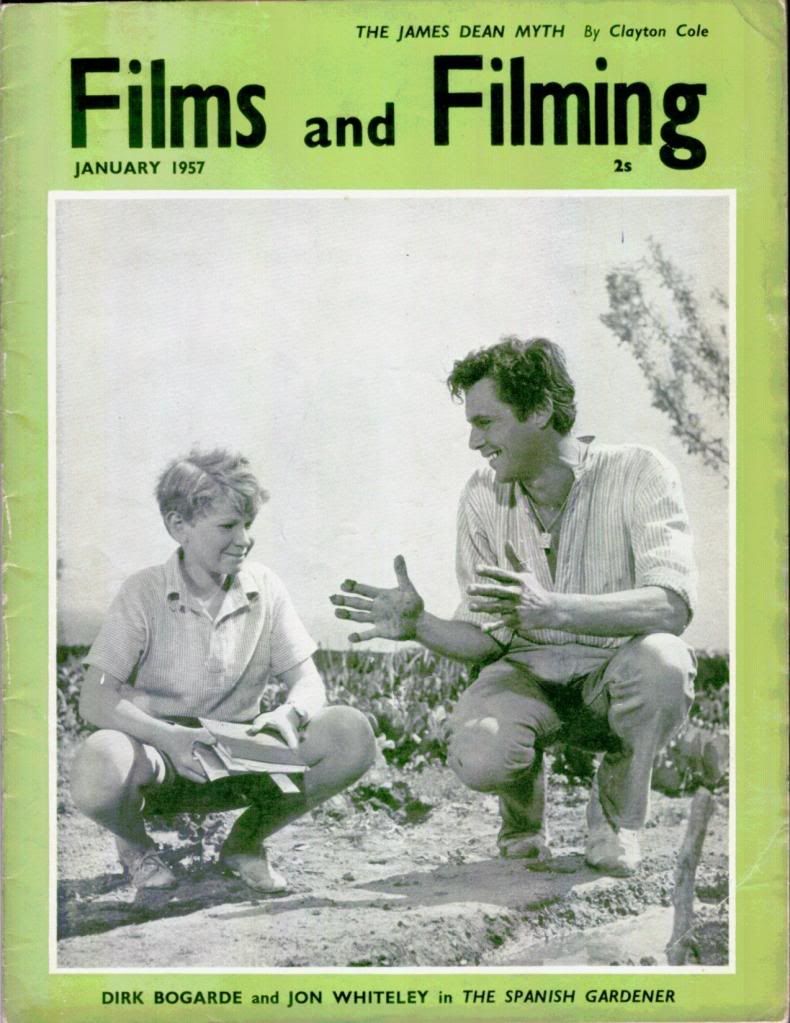

Back in Europe he made “The Spanish Gardner” with Dirk Bogarde again and Maureen Swanson. His final film was “The Weapon” with Steve Cochran in 1957. He is an eminent art historian in Oxford.

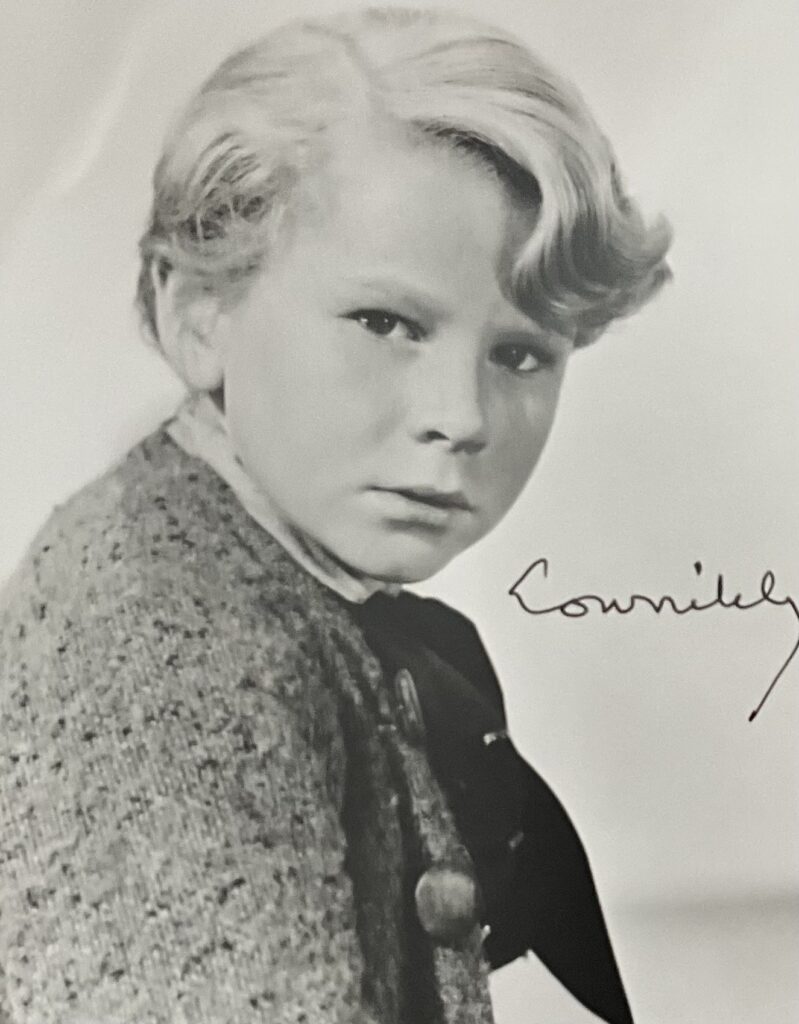

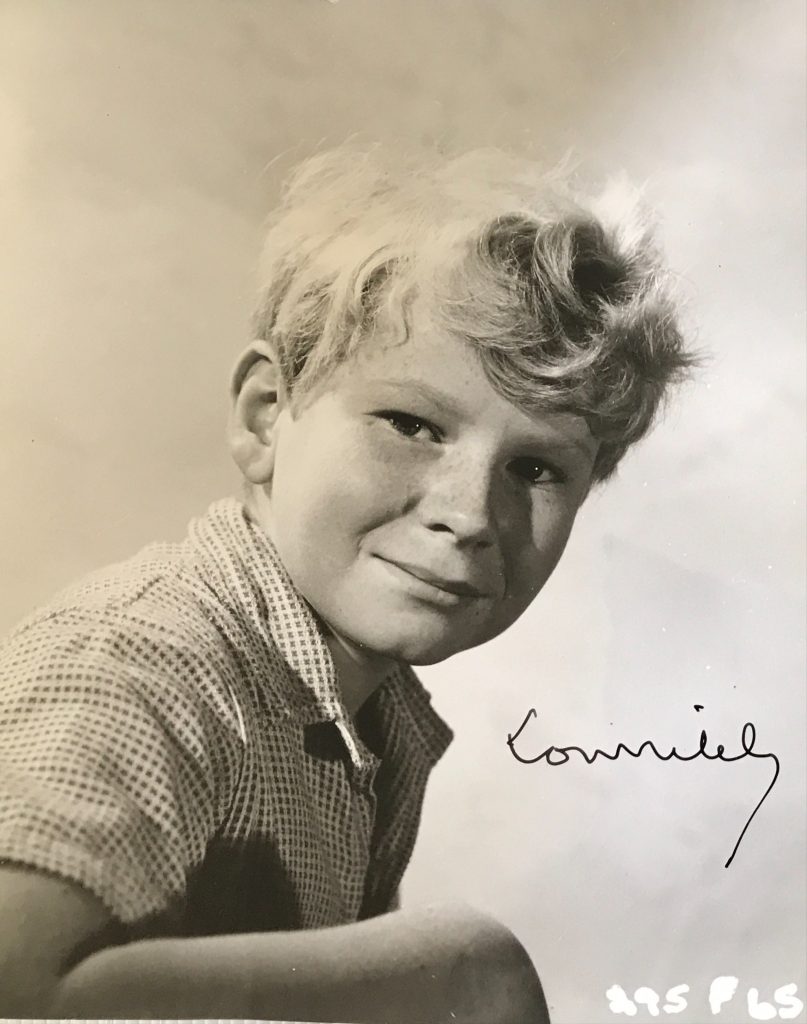

Gary Brumburgh’s entry:Amazingly talented child star Jon Whiteley was born on February 19, 1945 in Monymusk, Scotland, and put together an enviable, albeit brief, career in 1950s film drama. This precocious talent started things off winningly by earning first prize for verse-speaking at the Aberdeen Music Festival when he was only 6.

This led to his indoctrination into films, making a highly auspicious debut but a year later with the suspenser The Stranger in Between (1952), co-starring as a young runaway abducted and subsequently befriended by fugitive Dirk Bogarde.

Although this intriguingly offbeat-looking, tousled blond appeared in only five films during his brief reign, he made an award-winning impression. His astonishingly natural performance as Harry in only his second film The Little Kidnappers (1953) so captivated critics that he, along with fellow child co-star Vincent Winter, was awarded an honorary, miniature “Juvenile Oscar” at the Academy Awards ceremony of 1954.

In this touching drama, the two boys play orphaned brothers who secretly adopt an abandoned baby after their grandfather’s refusal to allow them to keep a pet dog. Other superb portrayals came Jon’s way as Fritz Lang‘s young protagonist John Mohune in Moonfleet (1955) oppositeStewart Granger, and in The Weapon (1956) as a lad who accidentally shoots his friend with a gun used long ago in a murder.

Jon also scored in The Spanish Gardener (1956) as the lonely son of a British consul living in Madrid who finds solace with (again) Dirk Bogarde as the title character.

Following a tiny spat of TV appearances, his career ended as quickly as it began.

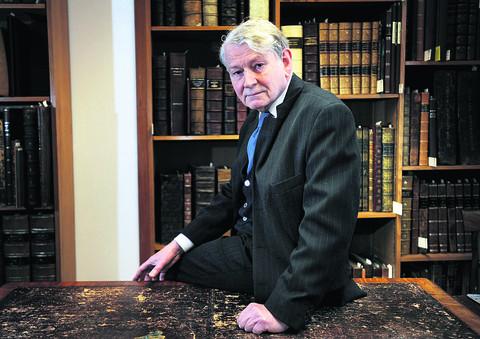

After abandoning the limelight, he became a respected art historian at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England.

– IMDb Mini Biography By: Gary Brumburgh / gr-home@pacbell.net

“Daily Telegraph” obituary in 2020

Jon Whiteley, who has died aged 75, was a highly distinguished and exceptionally revered museum curator, whose career in the world of art was preceded by an entirely unexpected backstory as an Oscar-winning child star in the 1950s.

Jon James Lamont Whiteley was born on February 19 1945 in Monymusk, Aberdeenshire. His father, Archie, was a headmaster, with the result that Whiteley grew up with an unusual respect for education, which was to prove decisive in determining the course of his later life.

At the age of six, his rendition of “The Owl and the Pussy-Cat” on a BBC radio broadcast from his school was heard by a talent scout, who grasped his potential, and over the next few years he made five feature films. Their casts alone make it clear that these were major productions.

Two – Hunted (1952) and The Spanish Gardener (1956) – saw him teamed up with Dirk Bogarde. In The Weapon (1956) he played opposite Herbert Marshall, while in Moonfleet (1955) he co-starred with Stewart Granger, George Sanders and Joan Greenwood. Most remarkably, the film brought him together with one of the greatest directors of all time, Fritz Lang, whose career stretched back to the birth of silent cinema in the 1910s.

However, Whiteley’s appearance in The Kidnappers (1953) was to have an even more spectacular aftermath, because at the Oscars for 1954 he and his fellow child star, Vincent Winter, received honorary awards for – in the words of the citation – their “outstanding juvenile performances”.

That year, On the Waterfront swept the board, winning Best Picture, Best Actor, and much else besides, but while Elia Kazan, Marlon Brando and others were basking in the applause at the ceremony, it was business as usual for Whiteley back in Scotland.

It was term-time and his parents saw no point in going all that way to collect the Oscar in person. It arrived through the post, and Whiteley was, above all, struck by its ugliness. In a recent interview he remarked: “It is at home somewhere, but I don’t think it is a particularly attractive object. It has no great charm.”

The opposite might be said of its recipient, although what is so remarkable about his beguiling screen presence in those five films is precisely that it seems to have nothing to do with acting. He seems to be quite unaware of the presence of the camera and just gets on with being himself, worlds removed from the stomach-churningly knowing cuteness which was, alas, all too common even among the best child stars.

Happily, courtesy of DVDs and the internet, these performances are now readily accessible in a way that could not even have been dreamt of in the 1950s.

Apart from a couple of television appearances – an episode of Robin Hood in 1957 and one of Jericho in 1966 – that was the end of the chapter. It had always been agreed that at the age of 11 his serious education should begin, and – apart from a mild regret at no longer having a chauffeur – he never looked back. The afterlives of child stars are often downhill all the way, but there are exceptions. What is certain is that few have achieved as much as Whiteley in their adult lives.

Whiteley was an undergraduate at Pembroke College, Oxford, and never left the dreaming spires. He stayed on and took a DPhil with Professor Francis Haskell on the 19th century painter Paul Delaroche, one of whose most famous paintings – The Princes in the Tower – could almost be a still from a Jon Whiteley movie.

After a brief spell as an assistant curator at the Christ Church Picture Gallery, from 1975 to 1978, he moved to the Ashmolean Museum as an assistant keeper in the Department of Western Art, remaining there until his retirement in 2014.

Nobody has ever known the Ashmolean’s collections the way Whiteley did, and he was the inevitable first port of call for numberless colleagues both within and beyond the museum. He was also a wonderfully welcoming presence in the print room; for novices, initial visits to such places can be intimidating, but Whiteley treated everyone with the same exquisite courtesy.

His other great achievement at the Ashmolean was in connection with his role in setting up the Education Department. A notoriously modest man, he did admit: “I am most proud of that.”

An old Oxford joke has a don answering the question “What is your field?” with the riposte “I do not have a field. I am not a cow.” For all that Whiteley was a great authority on his first love, French art, and was appointed a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2009, his scholarship was heroically wide-ranging both across space and time in an age of increasing specialisation.

In the context of France, as well as books on Ingres and Lucien Pissarro, he moved effortlessly beyond the 19th century, writing the catalogue of an important Claude Lorrain exhibition at the British Museum, cataloguing the French drawings at the Ashmolean in two volumes, the first being devoted to Étienne Delaune and the second covering the period from Poussin to Cézanne. A few months ago he just managed to complete his catalogue of the museum’s holdings of French paintings after 1800 before his final illness.

As if all this were not enough, he produced memorable books on Oxford and the Pre-Raphaelites in 1989, and on the Ashmolean’s collection of stringed instruments in 2008.

Fittingly, since an initial ambition to be a painter had led him to his chosen métier, he wrote with all the flair and understanding one might hope for from an artist. A compelling and much-loved lecturer, he also won undying devotion from his undergraduate – and, perhaps especially, postgraduate – students.

Jon Whiteley first met his wife Linda, also an art historian, in a library when they found themselves reaching for the same book. Marrying in 1972, they gave the impression of remaining of one mind for evermore, and had a son and daughter.

Jon Whiteley, born February 19 1945, died May 16 2020