Peter O’Toole obituary in “The Guardian” in 2013.

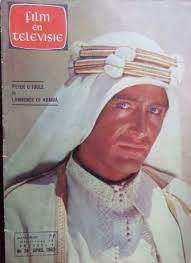

Peter O’Toole was a great actor, has just announced his retirement from acting. He was born in 1932 and is an Irish actor of stage and screen. O’Toole achieved stardom in 1962 playing T. E. Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia and then went on to become a highly-honoured film and stage actor. He has been nominated for eight Academy Awards – for Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Becket (1964), The Lion in Winter (1968), Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1969),The Ruling Class (1972), The Stunt Man (1980), My Favorite Year (1982) and Venus (2006) – and holds the record for the most Academy Award acting nominations without a win. He has won four Golden Globes, a BAFTA and an Emmy, and was the recipient of an Honorary Academy Award in 2003 for his body of work. He died in 2013.

The Guardian obituary by David Thompson:

Katharine Hepburn, his consort in The Lion in Winter (1968), once told Peter O’Toole that he was profligate with his talent as an actor. But perhaps O’Toole’s metier was always risk. Even in Lawrence of Arabia (1962), when he was not quite 30, he looked like an elegant wreck, dipped in suntan, his eyes full of fever. O’Toole, who has died aged 81, made his height, his giddy conviction and his theatricality hold that epic together. He was a freed bird in white robes, yet he shuddered like a schoolboy at the thought of torture.

Was O’Toole a great actor? Some said so – not least those who watched him grow up at the Bristol Old Vic in the 1950s. Did he sometimes stray into misguidedness or grotesquerie? Did he occasionally seem “unwell”? He is remembered for the disaster that was his Macbeth at the London Old Vic in 1980 – a performance that sold more steadily the more furiously it was debunked. But that was half the point to being O’Toole. He was a phenomenon and, night to night, moment to moment, you might shift your opinion as he zigzagged in the crosswinds of his own turbulent imagination. He coincided with the method, or realism in acting, but he ignored it.

O’Toole was plainly fascinated by ham acting and theatrical travesty – in one of his most entertaining films, My Favourite Year (1982), he played an actor, Alan Swann, a swashbuckler in the tradition of Errol Flynn. It earned him his seventh Oscar nomination but he lost to Ben Kingsley for Gandhi. Seven Oscar failures was a rueful glory he shared for a while with his old pal, Richard Burton. In 2003, he was awarded an honorary Oscar. He accepted but did not agree to be finished, There would be an eighth “failure” – his resplendent record.

O’Toole was born, he said, in Connemara, western Ireland (others say Leeds, where he grew up), the son of a wandering bookmaker. They were apparently following the horses at the time, but the family moved about a lot. He went to a Catholic school in Leeds and learned to read at an early stage. He was a teenage boozer, getting into scrapes and fights; wrapped parcels for a living for a while; and tried journalism on the Yorkshire Evening Post. He was told his writing was too colourful. After he and a friend hitchhiked to Stratford-upon-Avon, where they sawMichael Redgrave in King Lear, he knew acting was what he wanted to do.

Having undertaken two years’ national service in the navy, in 1954 he entered the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, where his fellow students included Alan Bates and Albert Finney. He was a rebel at the acting school, often at odds with his teachers, but he stood out at a time when a new provincial realism was creeping into British acting. Somehow, he could make Connemara and Leeds sound Athenian. After graduating, he got the job at Bristol. In three years there, he played more than 50 roles. These included Vladimir in Waiting for Godot (his favourite play), Alfred Doolittle in Pygmalion, Jimmy Porter in Look Back in Anger, the dame in pantomime, and a Hamlet that drew Peter Hall and Kenneth Tynan down to Bristol. He often played men older than he was, and his model at Bristol was Eric Porter – “because of his great looseness and power”.

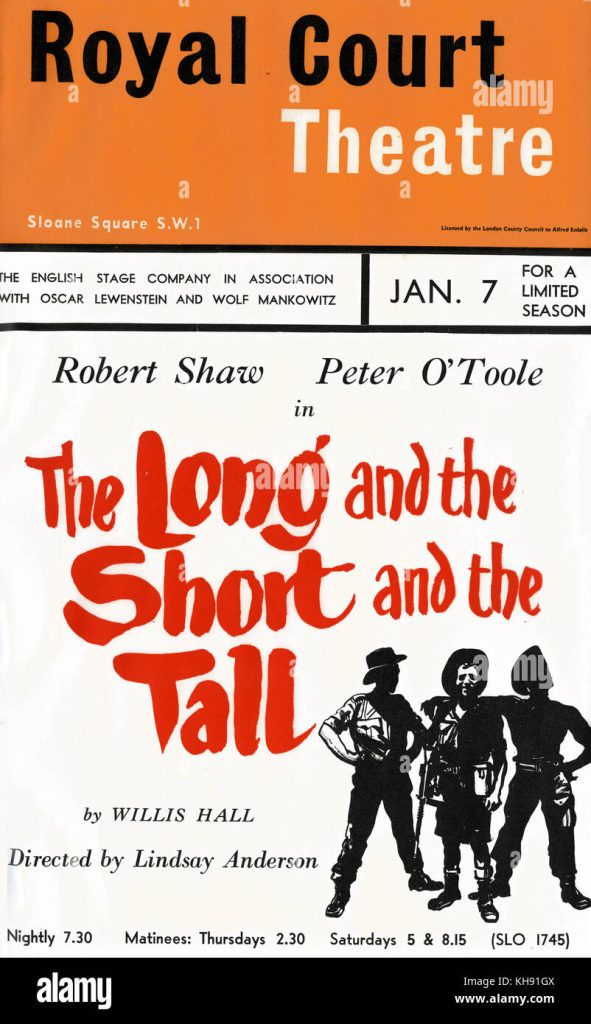

He left Bristol in 1958, and did Willis Hall‘s The Long and the Short and the Tall in London in 1959 (directed by Lindsay Anderson, with Terence Stamp as his understudy). From there, he went to Stratford for a season, where he played Shylock in a 1960 production of The Merchant of Venice. His Portia, Dorothy Tutin, graciously stepped aside at the final curtain to signal the debut of a new star. He was also Petruchio, opposite Peggy Ashcroft, in The Taming of the Shrew.

By then he was married to the actor Siân Phillips and they had the first of two daughters. It was a marriage full of fights and reconciliations, but all his friends testified to O’Toole’s deep devotion and need for a wife who was his equal in most dramatic flights.

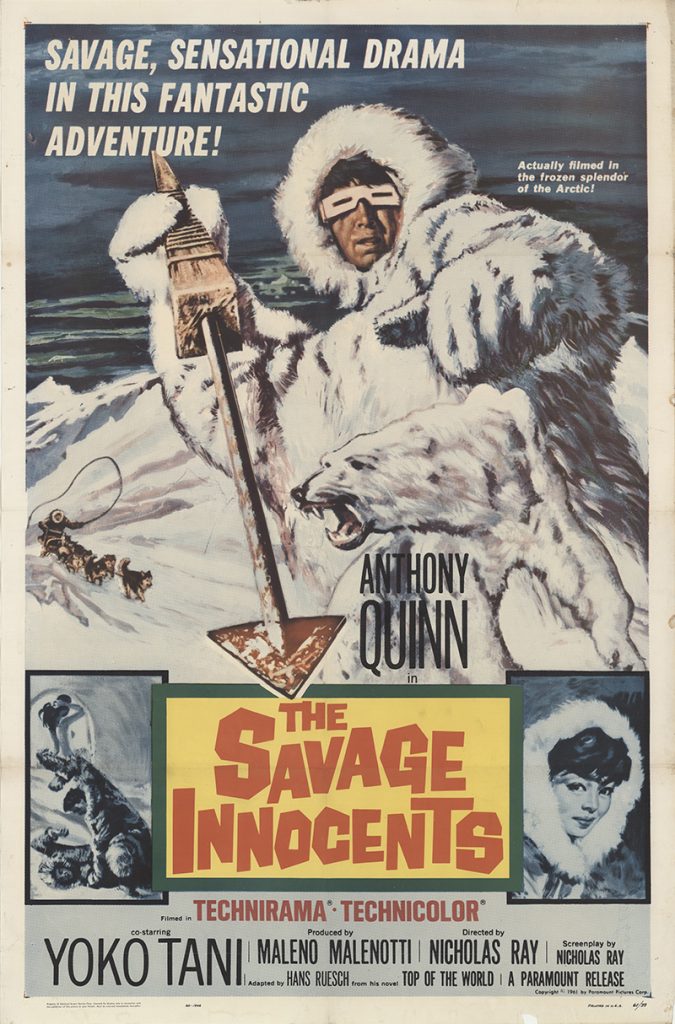

The theatre was poised for its great new talent, even if a few critics noted his tendency to “bark” out the words, but the movies already had their hooks in him. In 1960 he had a small part in Kidnapped, an odd one in Nicholas Ray’s The Savage Innocents and a much better one in The Day They Robbed the Bank of England. He was being talked about. Elizabeth Taylor even interviewed him for Mark Antony in her forthcoming Cleopatra (1963). They met, he whipped her at backgammon, and they agreed to disagree.

It was in 1962 that he was cast by David Lean as a far too tall, much too florid, yet riveting TE Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia. Sam Spiegel, the producer, had wanted Finney (and Marlon Brando before him), and they never got on well. But Spiegel did say O’Toole had “probably the most heady blend of sensitivity and vitality I have known in an actor”. It was a big picture, of course, and O’Toole was often rebellious and difficult. In hindsight, the character and the film are not always clear, but the faults are more in the screenplay than in the acting. He was nominated for an Oscar, and lost to Gregory Peck for To Kill a Mockingbird.

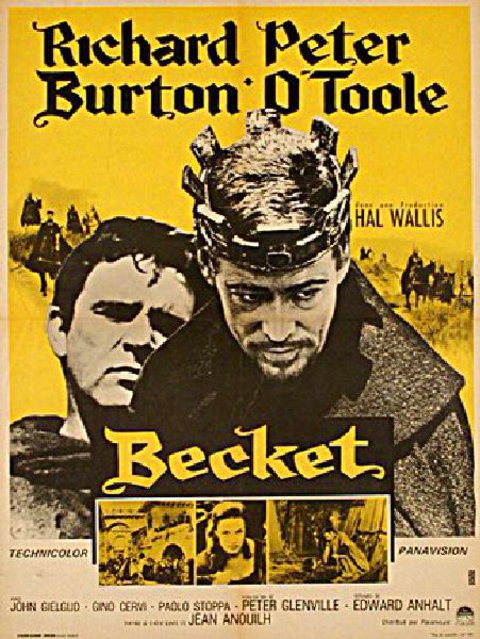

He went straight into another movie, Becket (directed by Peter Glenville, 1964), with Burton, and he elected to do Brecht’s Baal on the London stage as it was the kind of rogue play no one else would touch. O’Toole was seldom in the mainstream. But since that flopped, Laurence Olivier honoured him by asking him to play Hamlet in the National Theatre’s London debut at the Old Vic – with Olivier directing. Everyone who had seen O’Toole’s Bristol Hamlet believed that it was more urgent than the London show.

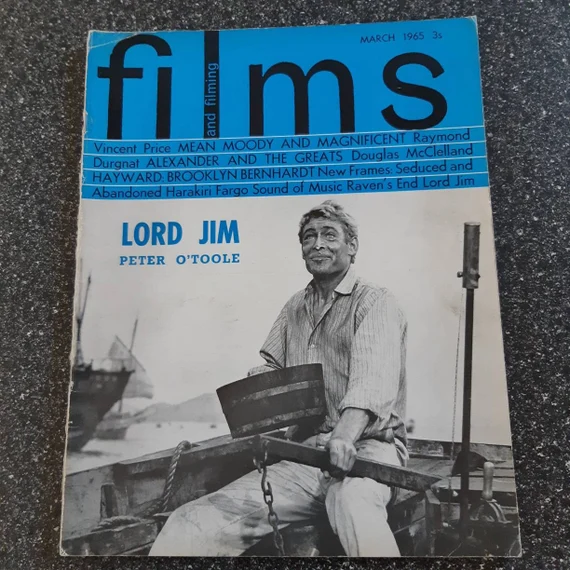

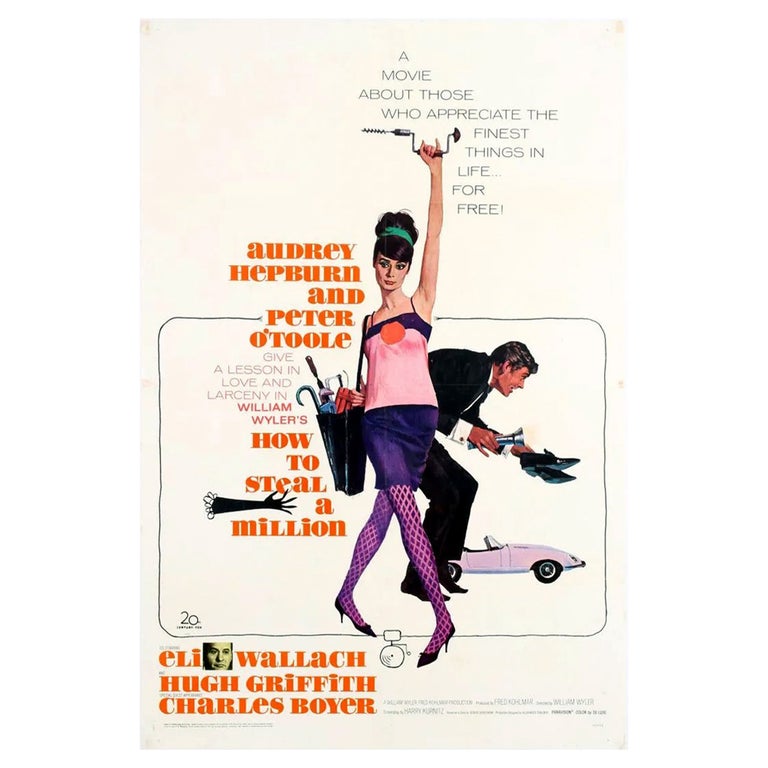

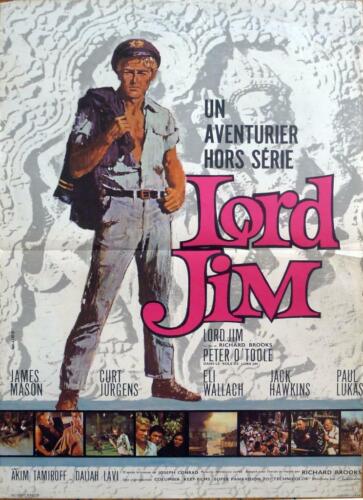

But O’Toole was now an international celebrity – there was another nomination for Becket (he and Burton were edged out by Rex Harrison in My Fair Lady). And so his movie career took over, producing dismay: Lord Jim (1965), a failure; What’s New, Pussycat? (1965), an interesting comedy that never lived up to all its starry contributors; How to Steal a Million (1966), a dud with Audrey Hepburn – viewers asked which star was thinner and more wide-eyed; The Bible: In the Beginning (1966) – as several angels – for John Huston; The Night of the Generals (1967); Great Catherine (1968); Murphy’s War (1971); Under Milk Wood (1972) – with Burton and Taylor; Man of La Mancha (1972); Rosebud (1975); Man Friday (1975).

It was an utterly unpredictable course for the actor whose Lawrence and Hamlet had seemed to command the world. There were silly, big-salary choices, to be sure, and the press was full of merry stories about O’Toole’s wildness, his drinking and his carefree attitude. But he had loved Donald Wolfit’s example; he was most excited by melodrama and going to the brink. He was already aware of another role, himself – O’Toole, in interviews, sitting at a bar, melodious and completely drunk. It was a grand part for which he did not have to learn lines.

The Lion in Winter was different – though, in truth, not quite as good as it is supposed to be. But O’Toole and Hepburn relished the union in which she was old enough to be his mother. That was another nomination – bowing to Cliff Robertson in Charly. O’Toole’s schoolteacher in Goodbye, Mr Chips (1969), far too sentimental, then lost to John Wayne in True Grit. The film roles that stand out are his deranged lord in The Ruling Class (1972) and the monstrous movie director Eli Cross in The Stunt Man (1980), two pictures that deliberately court extremism, and which might have been written for O’Toole. He was outstanding in both, but his bravura left vague the question of just how good the films were. He was nominated for both – and he lost to Brando in The Godfather and Robert De Niro in Raging Bull. That was a mark of cult work, true to his private spirit, but not close to the public pulse.

For several years he was away from the London stage, yet he worked in Dublin and in 1973 returned to Bristol for a season – working for next to nothing and playing a fine Uncle Vanya. In 1975, he was found to be suffering from pancreatitis. He underwent surgery, lost much of his stomach, then came back from it all to appear in a good adaptation of Geoffrey Household’s novel Rogue Male for British television in 1977.

In 1979, his marriage ended. That year he appeared as Tiberius in theBob Guccione-sponsored version of Caligula, a fairly sordid movie – and unfortunately compared with the BBC’s version of I, Claudius (in which his wife had been a shining player). Far more controversial was his Macbeth, at the London Old Vic in 1980, directed by the film-makerBryan Forbes, with Frances Tomelty as Lady Macbeth. It was not just that critics deplored the concept, the stagecraft and O’Toole’s own playing (monotony was frequently mentioned). Rather, it was the sense that O’Toole had set himself up against the world – that he even fed on the rebukes.

He married the actor Karen Brown in 1983; they had a son, Lorcan, but the marriage did not last long. The work, meanwhile, was often reckless and indifferent. Far from a versatile actor, he had become someone who could play only versions of himself. In which case, in 1989, he was blessed by providence. It came in the form of Keith Waterhouse‘s play Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell. O’Toole took the part of the alcoholic, fatalistic and self-destructive Spectator columnist with laconic restraint. It played every night to standing ovations and may have been the triumph of O’Toole’s life. Yet there was also his tactful, delicate portrayal of the English tutor in Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor (1987).

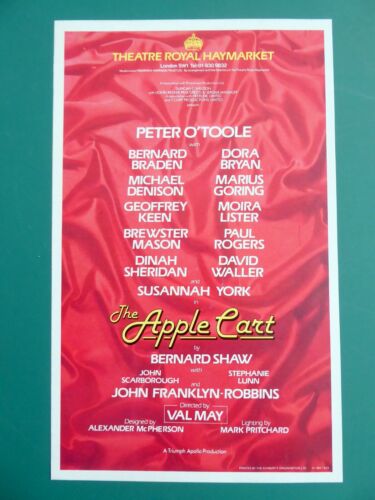

In 1982, he did George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman in London, and sometimes wavered as he strolled across the stage. On screen, he did almost anything – Svengali (1983), Supergirl (1984), Club Paradise (1986). Much was awful, nothing was dull. And then, in the 1990s, he found another self, the literary autobiographer, and published two volumes about his early life, under the title Loitering With Intent. More atmospheric than factually helpful, they were the works of a real writer and helped alter his public reputation.

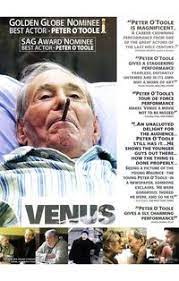

With his honorary Oscar, did he think of retiring? Out of the question. He did Bright Young Things (2003), directed by Stephen Fry; he played President Paul von Hindenburg in Hitler: The Rise of Evil (2003); he was an incredulous Priam in Troy (2004) and Casanova as an old man in the 2005 mini-series starring David Tennant. Then grace fell upon him, like a fine rain. Hanif Kureishi wrote, and Roger Michell directed, Venus (2006), a small story about a small-time, dying actor and a young woman. It was as touching as anything O’Toole had ever done. He got an eighth nomination, and smiled as the prize went to Forest Whitaker for his Idi Amin in The Last King of Scotland. Still he worked on, and it was characteristic that his Pope in the TV series The Tudors (2008) was as lowdown as his derelict in Venus had seemed aristocratic. In Michael Redwood’s film Katherine of Alexandria, due for release next year, he plays the Emperor Constantine’s orator, Cornelius Gallus.

What can one say, in summary, of so many astonishing performances by a man who had become a warning figure for young actors? He was one of those who make us ponder the terrible stress of the job and its art, its curse and its inspiration.

He is survived by his daughters, Kate and Pat, and Lorcan.

• Peter Seamus O’Toole, actor, born 2 August 1932; died 14 December 2013

The Guardian obituary website can be accessed on-line.