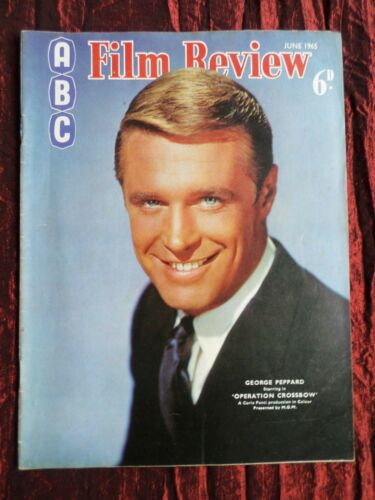

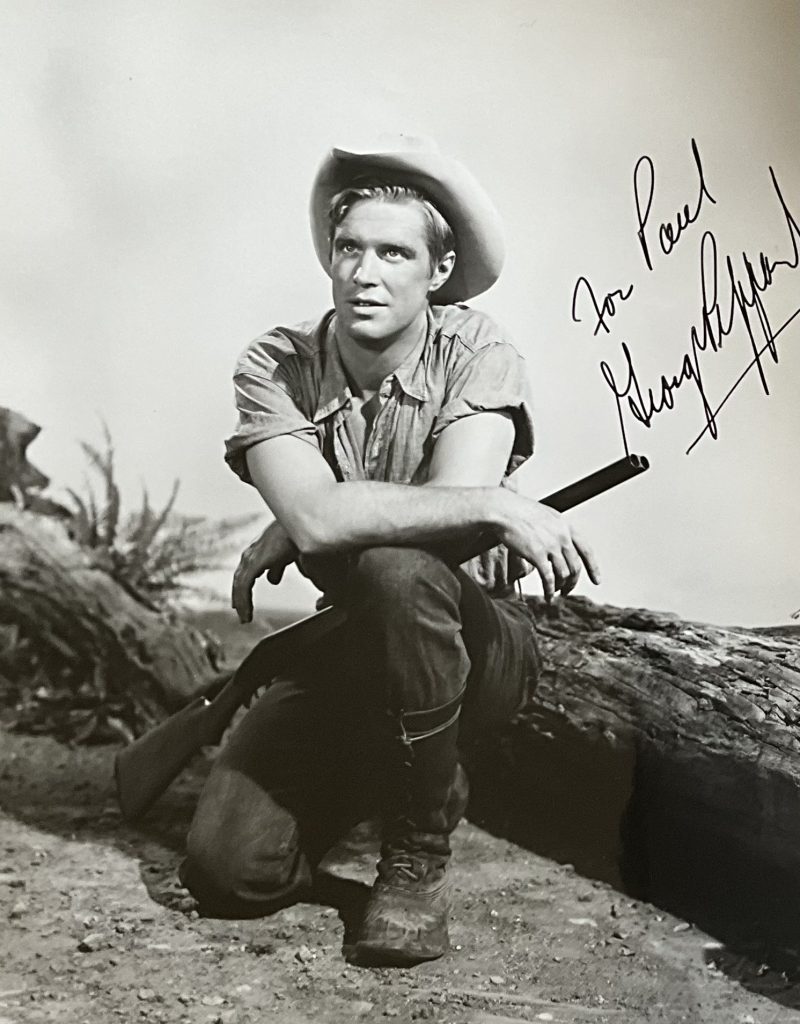

George Peppard

David Shipman’s “Independent” obituary:

BREAKFAST at Tiffany’s seemed a sophisticated piece when it came out in 1961, directed by Blake Edwards and written by George Axelrod from the novella by Truman Capote. The sexually ambiguous ‘I’ of the story, the struggling writer based on Capote himself, had become a full-blooded practising heterosexual – involved with a lady known only as ‘2E’ (played by Patricia Neal), who leaves him dollars 300 on the bedside table after their rendezvous. To the strains of ‘Moon River’, he gives her up for Holly Golightly, who is played by Audrey Hepburn.

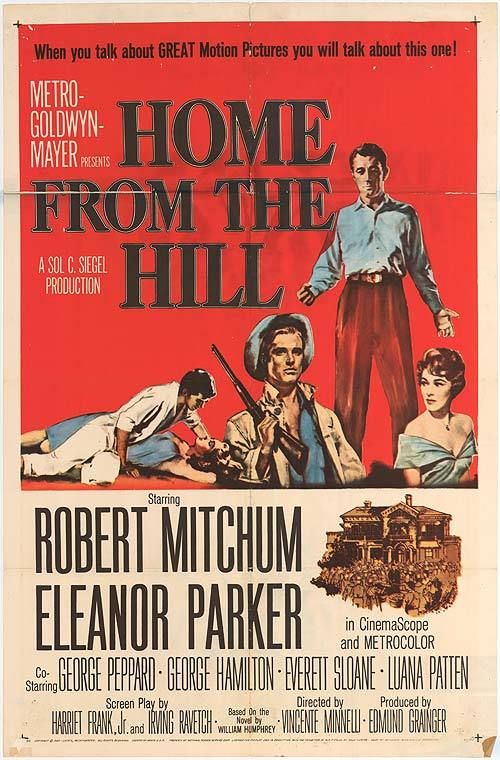

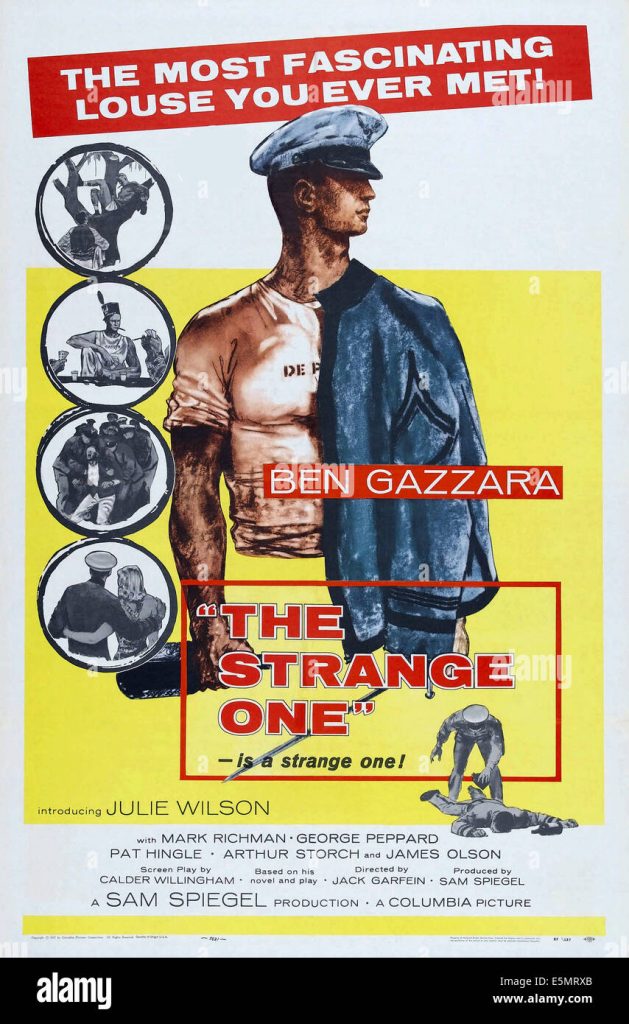

George Peppard played the role, that of the all-American boy gone to seed who rediscovers Real Values when he finds True Love. Peppard himself had no difficulty in hinting at the decadence of the character, and indeed in his first film he had played a first-year student at a military academy which was a hotbed of perversion and corruption – The Strange One (1957), adapted from Calder Willingham’s novel End as a Man. Peppard played a victim, but there was a glint in the eye, a flick of the tongue, which suggested that he could not wait to be the next school bully. He continued to be promising in his next few films, and something more than that in Home from the Hill (1959), as the hero’s illegitimate brother, investing his scenes with warmth and humour.

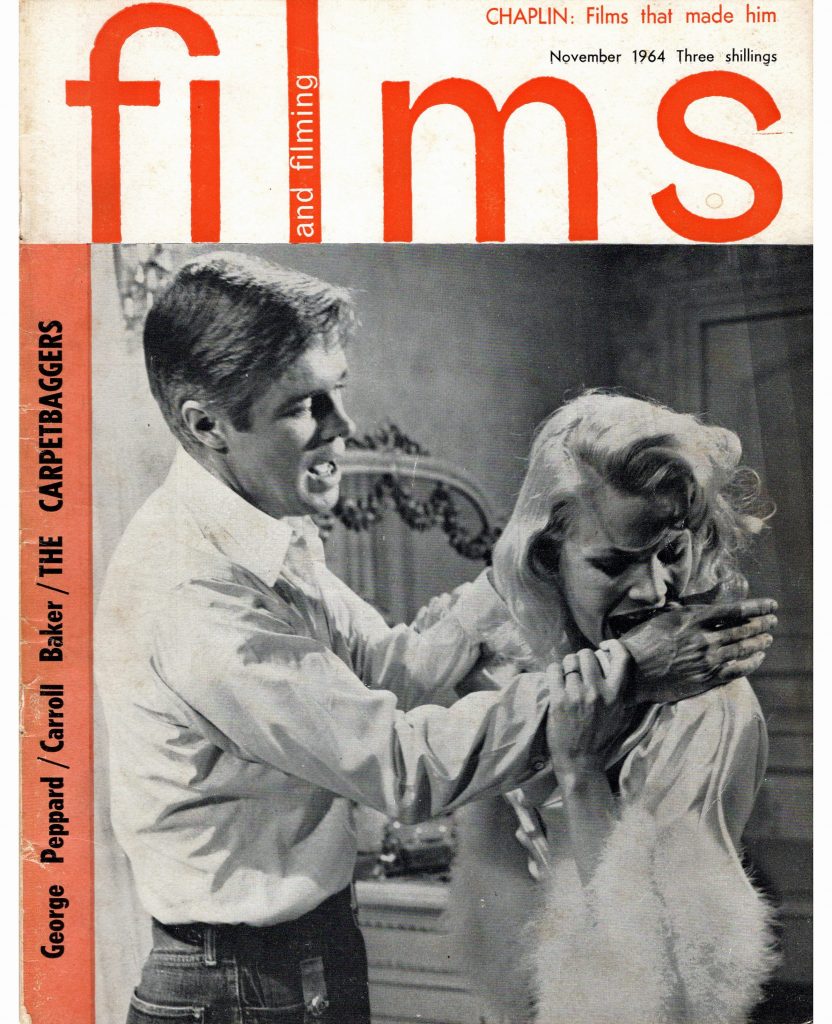

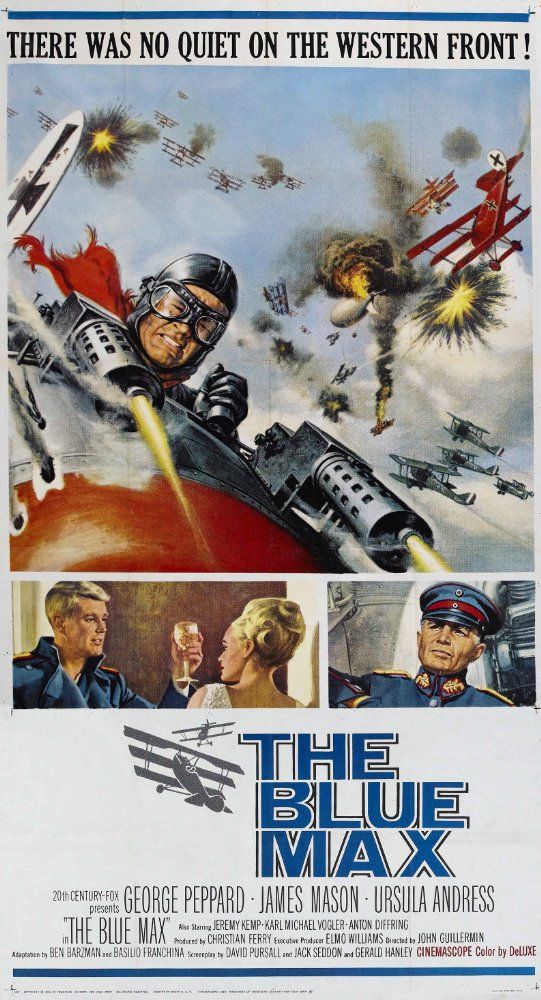

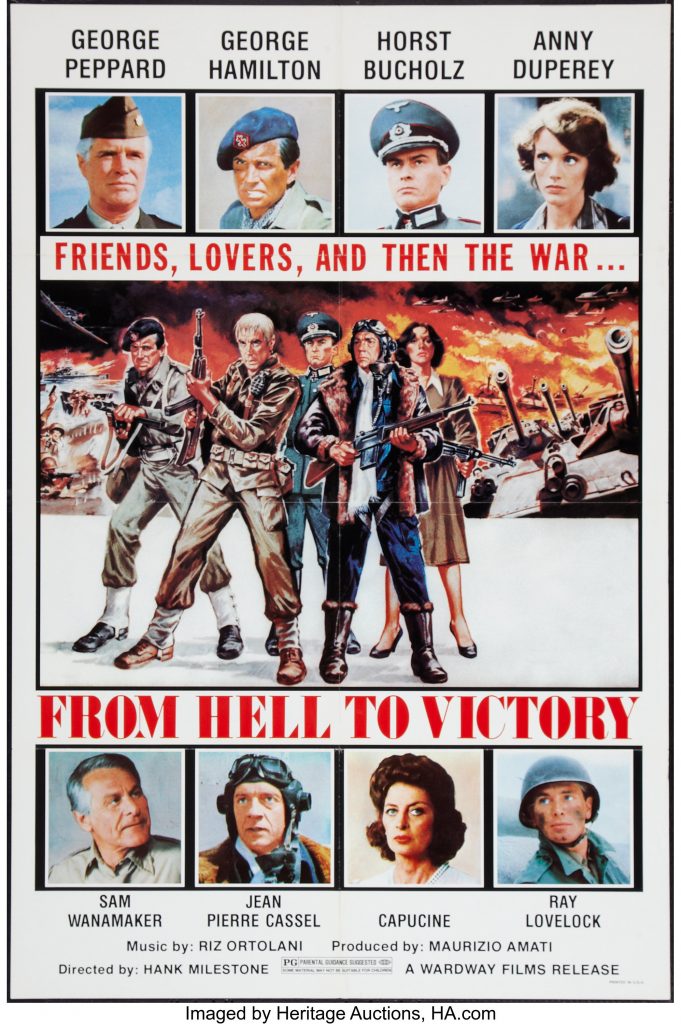

Breakfast at Tiffany’s made Peppard a star, and he appeared in a number of important pictures over the next few years, eventually achieving billing over such names as James Mason, Sophia Loren and Alan Ladd. The titles included How the West was Won (1962), The Victors (1963) and Operation Crossbow (1965). In The Carpetbaggers (1964), he played an unscrupulous playboy modelled on Howard Hughes, as first written up by Harold Robbins in his bestseller of the same title. Peppard had his best screen chance in John Guillerman’s The Blue Max (1966), as an ambitious working-class member of a crack German officer corps, despised by his aristocratic colleagues and determined to prove, by fair means or foul, that he is better than any of them. It was his last major film, which is doubly curious because, like The Carpetbaggers, it was a very big movie at the box-office. With a couple of hits like these, an actor can coast for two or three years, but after Rough Night in Jericho (1967), a western with Jean Simmons and Dean Martin, Peppard was offered little of interest.

This was partly his own fault. In 1965 he was making Sands of the Kalahari for Cy Endfield and Stanley Baker, who expected it to rival the popularity of their earlier Zulu. Peppard walked out during filming, to be replaced by Stuart Whitman. The film not only failed, but the industry looked askance at Peppard, never trusting or liking any actor who causes shooting to begin all over again. With his cool, blond baby-face looks and a touch of menace, of meanness, he had established a screen persona as strong as any of the time. He might have been the Alan Ladd or the Richard Widmark of the Sixties: but the Sixties didn’t want a new Alan Ladd. Peppard began appearing in a series of action movies, predictably as a tough guy, but there were much tougher guys around – like Cagney, Bogart and Robinson, whose films had now become television staples.

John Guillerman, making his first two Hollywood films, cast Peppard in the thrillers New Face in Hell (1967) and House of Cards (1968). In the second of these he was an expatriate American caught up in the dirty tricks of the French political right, and in the first a down-at-heel private eye. Peppard’s private eye brought him an offer to play another, in a television series, Banacek. It ran from 1972 to 1974 and brought renewed acclaim to Peppard and several movie offers. He chose to play a busted cop who sets out to clear his name in Newman’s Law (1974). He himself produced, directed and starred in Five Days from Home (1978), playing another ex-lawman, one who this time has been convicted of the manslaughter of his wife’s lover; the film went direct to television.

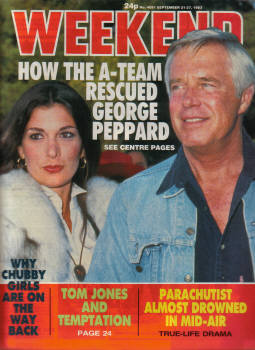

When Peppard returned to that medium, it was as Hannibal, the grinning, cigar-chomping leader of The A-Team, an NBC series which ran from 1983 to 1986. Righting wrongs, correcting or uncovering injustices, the A-Team went about their work with rare good-humour and a considerable amount of violence, explosive if not bloody. They were very popular, particularly with children, but the show was expensive to produce and needed the injection of new ingredients to hold its audience; and the producers preferred to put it into syndication.

More recently, Peppard had returned to the stage, and was in London briefly in 1990 in the two-hand play Love Letters, opposite Elaine Stritch. In 1992 he embarked on a tour of The Lion in Winter with Susan Clark.

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.