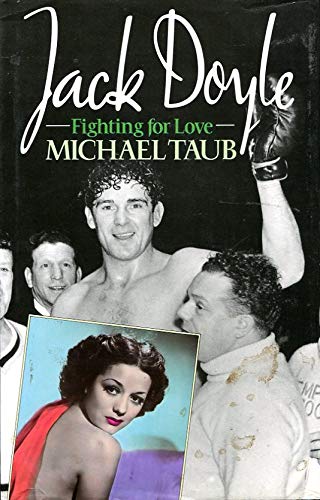

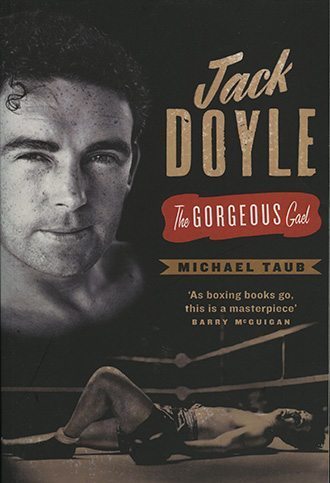

Jack Doyle was a very famous Irish boxer in the 1930’s who wnet to Hollywood and made two films there, “McGlusky The Sea Rover” (1934) and “Navy Spy (1937)”. He was born in Cobh in 1913 and died in Paddington, London in 1978.

“Independent.ie” article from 2007 by Ciara Dwyer:

On New Year’s day there will be a documentary on RTE 1 about Jack:Jack Doyle — A Legend Lost.

Doyle’s friend Johnny O’Boyle tries to explain to me what Jack was like. Then he sighs and says, “I wish you could have met him. Jack was larger than life. If you had the job of writing a script of a boxer, you couldn’t top the Jack Doyle story.”

So who was Jack Doyle? And what made him so special?

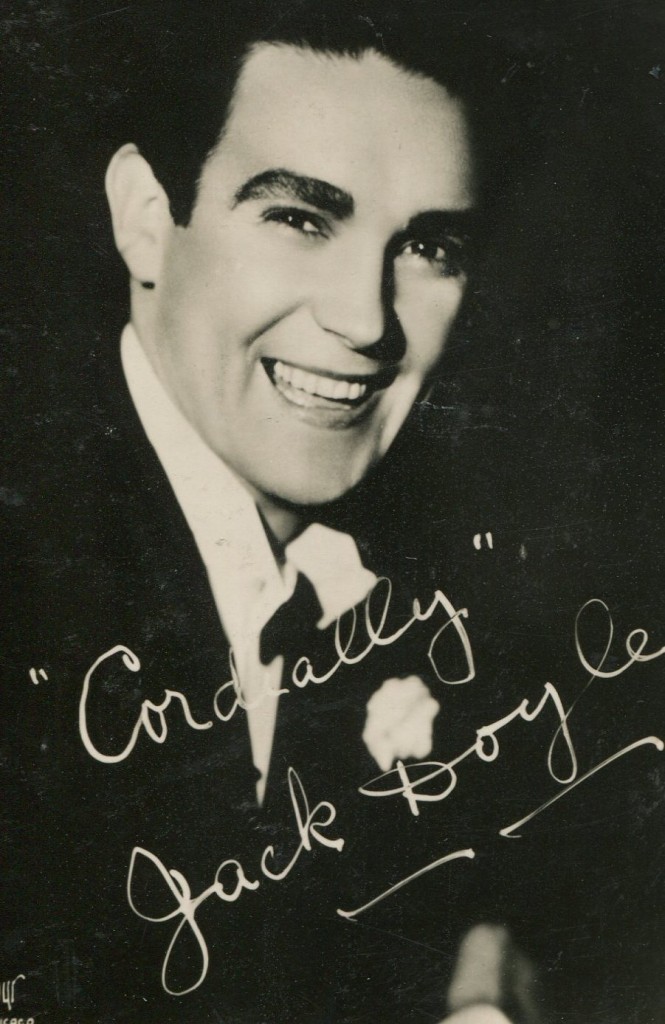

When God was giving out gifts, he was lavish with Jack Doyle. Jack was six foot five, had the right hook of Jack Dempsey, the looks of a film star and a lilting tenor voice like Count John McCormack’s. He was almost too much. Having an easy beginning is not always advisable, and so it was with Jack. He didn’t have to struggle to use his talents or graft like any other boxer. With a right hook like his, he saw no reason to exert himself with disciplined training or daily work-outs at the gym. Life and success came too easy to him. This was eventually to be his downfall.

Jack Doyle was christened Joe, but once he read a book about the boxer Jack Dempsey, that was it. He knew he would have to change his name. As it was, he was beginning to get a name for himself anyway, for being proficient with his fists.

“There was a butcher in Cobh called Tim McCarthy and he took a great shine to Jack,” Taub tells me. “He wrote to the Daily Mail, saying, ‘We have a great champion here and he keeps knocking out all the seamen.’ They would play cards on the quays and accuse him of cheating. Jack was only 14 at the time but he kept knocking out these big burly seamen. Tim sent his letter to Geoffrey Simpson, who was one of the most famous boxing writers of the day. Simpson couldn’t do anything to help Jack but he remembered the name and years later went to see him boxing, when Doyle was in Windsor in the Irish Guards.”

Up until then, Jack had been working, shovelling coal in Cobh, which was known as Queenstown back then. He came up with the idea of going to London to join the Irish Guards with the sole purpose of improving his boxing skills. Straight away, he was a star in the ring.

“It was only inter-unit boxing,” Taub explains, “but Geoffrey Simpson came down to see him box at Windsor and wrote a piece saying, ‘This boy is big enough to beat the world.’ Then all of Fleet Street flocked down to Windsor to see him. He never lost in the army, so he had this fame before he even stepped out of uniform. A boxing promoter called Dan Sullivan bought him out of the army and the rest is history.”

This instant success was the ruination of him. He was only 18 when he came out of the army. They used to say he was like the Rudolph Valentino of the ring. Jack was only a raw boy from Cobh and women were falling at his feet. After army life, he had all this lavished on him and he had no parental guidance. (His family were back in Cobh.)

“He had this hunger to make his way and to provide for his family in Cork but it all came so easy to him,” Taub says. “Many other boxers were slaving away in the gym, honing their talents but Jack was a star just with his big, right hand. He grew to dislike the daily grind of training and other boxers became resentful of him. He found fame too easy.”

In his first 10 fights, Jack wrapped up 10 quick victories in 15 rounds. He was the first Irishman to box for the British heavyweight title. He was fighting against Jack Petersen but was disqualified for hitting too low. The boxing board of control took draconian measures — it confiscated his prize money of £3,000 and banned him from fighting for six months. Jack had been a trusting soul but he became cynical about it all. He was hitting low because he had syphilis and in those days there were no anti-biotics to clear it. Jack had told a friend that a gangster’s moll was fed to him to give him a dose of the clap, so that their bets were safe on Petersen.

But while the boxing ban was on him, he fell back on his other talents — singing. He had met Count John McCormack and had had lessons with his manager, Dr Vincent O’Brien. He toured, doing a show that included his favourites, like Macushla and I’ll Take You Home Again Kathleen. And the record label Decca was so impressed with his voice that it offered him a recording deal.

Jack got a chauffer and a butler and took elocution lessons, which made him sound like Trevor Howard in Brief Encounter. Before long, Hollywood beckoned and he was starring in films as an action hero. In America he met his first wife — the actress Judith Allen. They were blissfully happy until Judith realised that he was a cad. As she said, “Jack just couldn’t resist sharing himself.” When she heard that he was caught up in another relationship, she sent him a one-word telegram: FINISHED.

The documentary also includes some of Taub’s own footage, when he interviewed her. She was wistful about their time together.

“And you know, he told me that he would never sing Macushla to anyone else for the rest of his life; [she sighs] Yeah, those were nice days.”

Jack moved on to Delphine Dodge, who was one of the richest women in America and part of the Dodge cars family. She was married when she met Jack but she did not let that deter her. He appealed to her on several levels. She was an accomplished pianist — so they had music in common — and Delphine was a champion speed-boat racer; and Jack appealed to this hunger for excitement. She paid off all Jack’s gambling debts and gave him $5,000.

In the end, when her family suspected Jack of being a gold-digger, they got someone to put a gun to his head and told him to get out of town, which he did.

Jack’s next wife was the Mexican film star Movita. She had been dating Howard Hughes but she stood him up to meet Jack. She was smitten by him. But again, he couldn’t resist temptation. Women clamoured for him and he gave in, again and again. While married to Movita, he had a one-night stand with Countess De Cadenet (grandmother of the television presenter Amanda). She told Taub about her night with Jack.

“I met Doyle in Al Byrne’s Pigalle Club in Soho in the early part of 1940. I was there with another showgirl, having a drink and Doyle was there on his own. He said, ‘Who’s coming home with me?’ He was six feet five and so handsome. He hauled me off to some shabby room — a real dump, which he used for screwing purposes … he exuded great charm and said nice things but once the business was done, it was ‘Out’. I realised then that the performance was unimportant to him. It was just the chase that appealed.”

When Jack had to leave America — his papers weren’t legal –Movita put a red carnation in his lapel and told him always to think of her when he wore one. In his final years in London’s Notting Hill, when money was tight, he made a point of buying a fresh red carnation every day.

Movita came to Dublin with Jack and they did a show together singing duets. The Irish people took them to their hearts, but all was not well offstage and sometimes onstage. Jack was drinking heavily and occasionally Movita would have to carry the show. Things got nasty when he started to hit her. She knew then that she had to get away. But when she was interviewed by Taub, she was far from bitter about her years with Jack Doyle: “I loved him then, I love him now and I guess I will always love him.”

JACK found the love of another good woman — Nancy Kehoe — but in the end, she could take no more of him and his beatings. She left.

Over the years, he earned huge amounts of money but he was swindled by several people.

Contrary to reports, Jack Doyle did not die in the gutter in London. One night he was in The Hoop pub in Notting Hill and he collapsed. A fellow Cork man called John Sullivan was sitting in the crowd with Jack and offered to take him home. Sullivan worked on the railways at night, but for some reason that night, he decided to stay home with Jack. He gave him blankets and then in the middle of the night, Jack came in to him, complaining of the cold. Then he started to haemorrhage. He died in St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington in 1978.

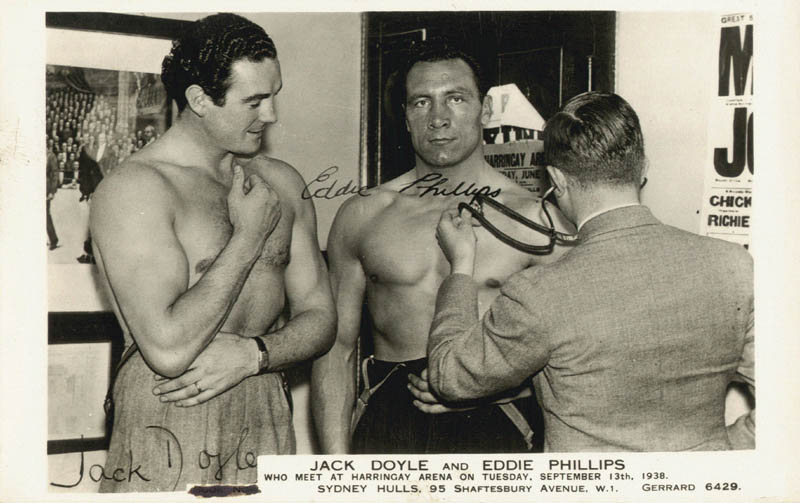

For all his affairs and physical violence, he will be remembered for his kind nature. The boxer Eddie Philips said that Jack was “a brute in the ring, but an angel outside of it”. And his motto was, “A generous man never went to hell.” While he had riches, he spread them around.

In the documentary, we hear Jack saying, “I’d do it all the same. I don’t regret a thing.” But Taub says, “What else could he say? He’d hardly admit the truth.”

The above “Independent.ie” article can also be accessed online here.