Janet Leigh is one of the key players from the Golden Age of Hollywood. She h as a good number of classic movies to her credit including “Little Women” in 1949, “If Winter Comes”, “Houdini”, “The Vikings”, “The Manchurian Candidate” in 1962 and “The Fog” in 1980. She was for a long time married to Tony Curtis and is the mother of screen icon Jamie Lee Curtis. She died in 2004.

Tom Vallance’s “Independent” obituary:

Jeanette Helen Morrison (Janet Leigh), actress: born Merced, California 6 July 1927; married 1942 John Carlyle (marriage dissolved), 1946 Stanley Reames (marriage dissolved 1948), 1951 Tony Curtis (two daughters; marriage dissolved 1962), 1962 Robert Brandt; died Beverly Hills, California 3 October 2004.

Janet Leigh played arguably the most famous screen murder victim in history. As Marion Crane in Alfred Hitchcock’sPsycho, she was the embezzler who, just after having a change of heart, is gruesomely knifed to death in her shower.

The scene, besides being genuinely shocking, has become one of the most analysed sequences on film, and the actress gave countless interviews regarding its filming and her personal attitude towards her role. At the time of the film’s making, she was its biggest star, and part of the scene’s impact was the audacious removal of her character only half an hour into the film.

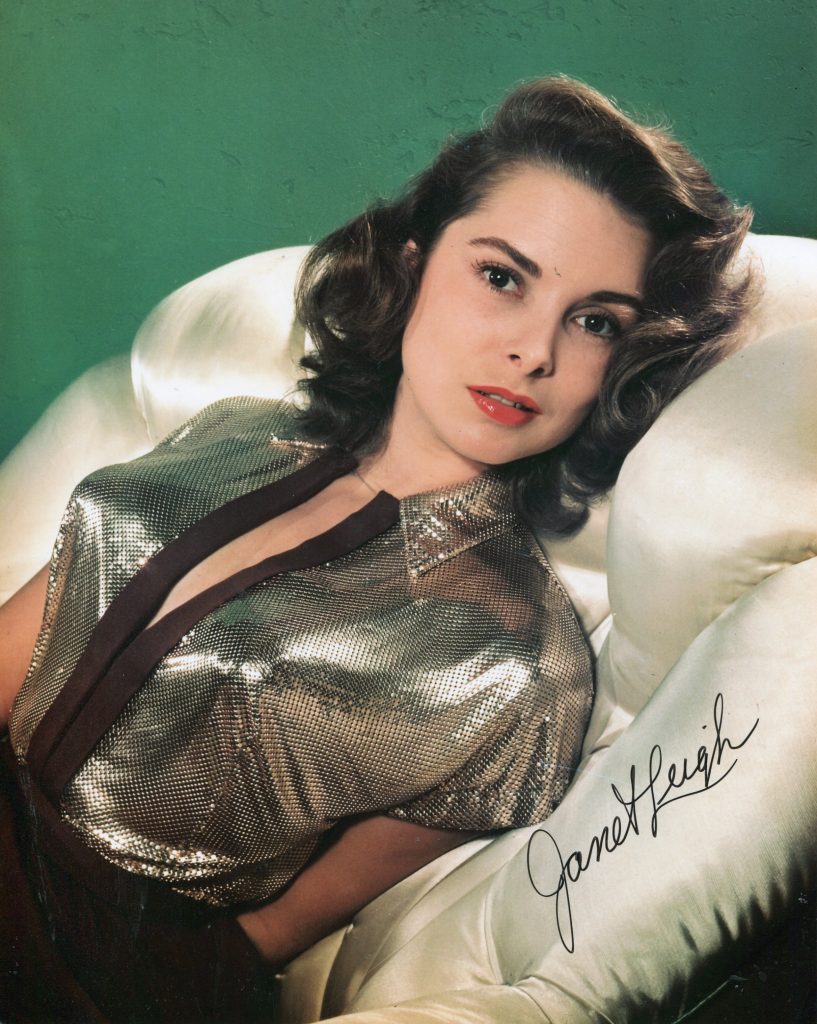

Though few audiences now come to the film unaware of the ploy,Psycho is a great enough movie for the knowledge to have no effect on its impact. However, it is not the only masterpiece in which Leigh appeared. Her impressive career included such fine works as George Sidney’s Scaramouche, Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil and John Frankenheimer’s The Manchurian Candidate. She was also one of the most beautiful ingénues of her time, had a marriage to the actor Tony Curtis that made them favourites of the fan magazines for several years, and was the mother of the actresses Jamie Lee Curtis and Kelly Curtis.

Born Jeanette Helen Morrison in Merced, California, in 1927, she was the only child of a sales clerk, Fred Morrison, and his wife Helen, who was of Scandinavian descent. Her childhood was unsettled, as her parents frequently moved from town to town. Leigh owed her discovery to the former MGM star Norma Shearer. In 1946, Leigh’s parents had taken jobs at the Sugar Bowl Ski Lodge in Soda Springs, California, where her father worked as a receptionist and her mother in the dining room. Shearer, on holiday with her husband, spotted Leigh’s photograph on her father’s desk and, taken with her fresh-faced beauty, asked for a copy to show friends in Hollywood.

Though retired, Shearer was influential and owned a large share of MGM stock. The result was a screen test. Leigh was still a student at the College of the Pacific, majoring in music (though already married to her second husband), when signed by MGM in 1947. “We were living over my aunt’s garage and the money was welcome,” she later said.

She had no acting experience, but her pretty looks and bright-eyed wholesomeness made her a pleasing ingénue, though one columnist wrote of an early performance, “She is over-eager, over-nice, over-everything.” The studio renamed her Janet Leigh, and, after some preparation with drama coach Lillian Burns, she tested successfully for the female lead opposite Van Johnson in the rustic drama The Romance of Rosy Ridge (1947).

Leigh recalled,

An established actress on the lot, Beverly Tyler, had practically been cast, but later I heard that Louis B. Mayer felt she was a little too sophisticated to play a farm girl. They wanted a more naïve type, and they sure got her.

She played another country girl in The Hills of Home (1948), starring the collie Lassie, and then a hapless young girl who becomes pregnant and commits suicide in an inane soap opera, If Winter Comes (1948). The critic James Agee labelled the film “pretty awful”, but praised “an overdone, but promising performance by Janet Leigh”.

Leigh was then cast in Words and Music (1948), a biography of the composers Rodgers and Hart. Richard Rodgers, who loathed the film’s inaccuracies, later said,

The only good thing about that picture was that they had Janet Leigh play my wife. I found that highly acceptable.

Leigh found the film exciting for the chance to work with Judy Garland. “I actually had a scene with her, which gave me goose bumps.”

In Fred Zinnemann’s bleak film noir Act of Violence (1949), she had her most demanding role to date as a housewife whose husband, a former prison-camp informer, is stalked by a vengeful survivor. She then made a perfect Meg March in Mervyn LeRoy’s loving transcription of Little Women (1949), a perennial favourite. “The picture has such wonderful warmth,” she said:

It kind of brings you back to the values we all had as children. June Allyson, Elizabeth Taylor, Margaret O’Brien and myself really did assume the aura of four sisters and had a ball. We cracked up all the time. Mr LeRoy was great – he put up with us and still turned out one of the most beautiful films I was in.

A less successful literary adaptation, of The Forsyte Saga, retitledThat Forsyte Woman (1949), cast her as the trusting June Forsyte who loses her architect lover (Robert Young) to her aunt, Irene (Greer Garson).

Leigh’s charms meanwhile had attracted the attentions of the millionaire producer Howard Hughes:

I was at Mr Mayer’s house one evening and was introduced to this tall, taciturn, thin man with a moustache. It was Howard Hughes, who had just bought RKO studios. As the evening wore on, I realised that he was being overly attentive, which I really did not appreciate. He was twice my age and, besides, I was dating someone else. He made me uncomfortable. Subsequently, I got to know him better, which made me even more nervous about him.

Leigh, who later stated that her parents frequently bickered throughout their lifetime, had married first at the age of 15, when she eloped with a 19-year-old named John Carlyle, but the marriage was annulled four months later. In 1946 she married Stanley Reames, a sailor and aspiring bandleader who hoped to break into the big band league when he journeyed with Leigh to Los Angeles. It was a time when the big-band era was coming to an end and he had little success. In 1948 he and Leigh were divorced, after which Leigh entered into a long relationship with the actor Barry Nelson.

In 1949 Howard Hughes and MGM agreed to a loan-out deal by which Leigh appeared in three RKO films. The first was a bright, romantic comedy, Holiday Affair (1949) co-starring Robert Mitchum, in which Leigh played a “comparison shopper”, who buys goods to compare their prices and value with those of the store that employs her.

Josef von Sternberg (“an unbearable dictator”) directed her second RKO movie, Jet Pilot, in which she played a jet-flying Russian spy converted to “the American way” by John Wayne (as an air-force colonel). It started shooting in December 1949, but was not released until 1957 because of the aviation enthusiast Hughes’s attempts to keep up to date with aircraft developments.

Her last RKO movie was a musical, Two Tickets to Broadway (1951), in which Leigh sang and danced with flair as a college graduate who joins two chorus girls (Ann Miller and Gloria DeHaven) in their search for stardom. Unusually for its time, the film featured television as its background rather than the theatre or movies. Hughes kept the film in production for several months ordering retakes in his search for perfection, though some averred that he simply liked to watch Leigh at work. “His pursuit continued,” said Leigh, “but he never caught me. Tony Curtis, a rising young actor at Universal, did.”

Leigh and Curtis met at a Hollywood party in 1950, and Curtis later recorded his reaction:

Her face was exquisite – and those beautiful bosoms and tiny waist. It just devastated me to look at this woman.

The pair eloped to Greenwich, Connecticut, in June 1951. They made an attractive young couple and were heavily featured in the fan magazines of the day. “There was no bigger pair,” wrote Curtis:

No other husband-and-wife team came close to us until Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, but that was 10 years later. They did it through scandal. We did it through the movies and people’s affection.

At MGM, Leigh continued to play undemanding ingénue roles, in some major films such as a superb version of Rafael Sabatini’s swashbuckler Scaramouche (1951), and Anthony Mann’s gripping western The Naked Spur (1953), and in such inconsequential comedies as Stanley Donen’s Fearless Fagan (1952) and Eddie Buzell’s Confidentially Connie (1953). At Universal, a weak musical with Donald O’Connor, Walkin’ My Baby Back Home (1953) wasted the talents of both its stars, with Leigh’s singing voice inappropriately dubbed by Paula Kelly.

She and Curtis then made a film together, Houdini (1953), a biography of the famous escapologist, directed by George Marshall. Reviews were mixed, but the chemistry of the stars was acknowledged (“Paired, they are a harmonious, ingratiating team,” said Daily Variety), and audiences flocked to see the young couple in their first co-starring feature. It was quickly followed by another, The Black Shield of Falworth (1954), an undemanding swashbuckler.

With her marriage to Curtis, Leigh had acquired a sexier and more mature image, and better roles were coming her way. Rogue Cop(1954), the last film under her MGM contract, was a gritty thriller with Robert Taylor and George Raft, and Pete Kelly’s Blues (1955) was a flawed but fascinating attempt to reconstruct the jazz world of the 1920s.

In My Sister Eileen (1955), a musical version of the hit play first filmed by Columbia in 1943, she was cast as Eileen, the prettier of two sisters who leave their small-town home to try their luck in New York City. The film had been intended as a vehicle for Judy Holliday, who was to play the other sister, Ruth, but she had seen Rosalind Russell play the role in the Broadway musical Wonderful Town, based on the same play. Wary of following in Russell’s footsteps, she turned the film down when the studio refused to pay for the rights to the Broadway score by Leonard Bernstein, Betty Comden and Adolph Green.

When Holliday was replaced by Betty Garrett, not as big a star at the time, the subsidiary romance between Leigh and Bob Fosse was built up, giving Leigh some charming song-and-dance moments with both Garrett and Fosse (with whom she had a brief affair). With tuneful songs by Jule Styne and Leo Robin, fine performances by Garrett, Leigh and upcoming Jack Lemmon, and outstanding dancing by Fosse and Tommy Rall, My Sister Eileen proved to be one of the best musicals of the Fifties.

Leigh was next asked by Richard Rodgers to audition for the forthcoming Rodgers and Hammerstein stage musical Pipe Dream. Offered the role, she first accepted, then turned it down when Curtis pointed out that it would mean being separated from him for at least six months. (Judy Tyler played the part in what became one the composing team’s less successful ventures.)

Leigh’s next film was to be one of her most memorable, Orson Welles’s baroque thriller Touch of Evil (1956). Leigh was initially puzzled when she received a telegram from Welles stating how delighted he was that they were to be working together. She knew nothing about the project, but Welles had correctly surmised that she would be so pleased at the idea of being directed by him that he would get her at a lower price than if he had to negotiate with her agent first.

She thought she had lost the role, though, when she broke her arm shooting a television movie just before filming was to start. At first Welles considered having her character, a young newly wed, sport a broken arm throughout the film, but he changed his mind and managed to shoot in ingenious ways that concealed the injury:

I did the entire movie with a broken arm and no one knew. During the motel sequence and less-clothed scenes, the doctor sawed the cast in half lengthwise. We would take it off, do the shot, and strap it back on again.

Leigh found Welles’s acceptance of improvisation fascinating, and entirely different to her later experience with the meticulously prepared Hitchcock. “With Mr Hitchcock the film is over for him before he even begins shooting.”

The renowned opening scene of Touch of Evil, a continuous shot of several minutes, started with a time bomb being planted in a car, then panned to a drunken man and a blonde leaving a café and getting into the car to drive towards the border. Leigh wrote,

The shot included Chuck [Charlton Heston] and me approaching the checkpoint, waited through our exchanges with the official and the passing through of the drunken man and his bimbo, lingered while we kissed, and zoomed to the convertible and the explosion in the distance. The technical prowess needed for this was beyond my comprehension.

The offbeat film about a corrupt cop and a honeymooning Mexican lawyer (Charlton Heston) who exposes him proved too non-linear for the studio, who later ordered retakes by another director. “Both Chuck and I resented changing it and bastardising it,” said Leigh, “because what we did made it almost normal.” Leigh later stated,

The release of Touch of Evil was disappointing. But it warms the cockles of my heart to at least know that it now is considered a cult classic and honours Orson Welles.

(The film has since been restored to a version approximating Welles’s original cut.)

In 1956 Leigh gave birth to her first daughter, Kelly Lee Curtis, then she returned to the screen as an English princess, Morgana, in the impressive epic The Vikings (1957), directed by Richard Fleischer and co-starring Kirk Douglas and Curtis. After giving birth to a second daughter, Jamie Lee Curtis, in 1958, Janet and Tony then starred in an amusing lightweight comedy, The Perfect Furlough (1959), directed by their good friend Blake Edwards, and followed it with another farce, Who Was That Lady? (1960).

Columnists sometimes pondered whether Leigh was sacrificing her career to her marriage, making inconsequential movies with her husband, who in between was acting in such prestigious films asSweet Smell of Success, The Defiant Ones, Some Like It Hot andSpartacus. But in 1960 Leigh was given a great role and the one for which she will be best remembered, that of Marion Crane in Psycho.

The early sequences of the film, depicting Marion’s stealing of the money, her encounter with a patrolman, her increasingly ominous night drive through the rain, her discovery of the remote Bates Motel and her equivocal conversations with the proprietor, display both director and star at their best. Of the famous shower scene, Leigh wrote,

The brilliant artist Saul Bass did a thorough storyboard for the shower-scene montage. Hitchcock diligently adhered to Bass’s blueprint. The combined endowments of these two gave us a course in fantasy . . . I believe that class of film-making was more effective than the current standard. The censorship obliged creators to find a way to show, without showing, thus giving the viewers liberal range for their imaginations.

Regarding consistent rumours (and Hitchcock’s own statement) that a model was used, Leigh insisted that only the scene where Perkins puts the body in a sheet and drags it to the car utilised a model. “Hitch told me there was no reason to subject me to the discomfort since it was a distant high angle anyway.”

Leigh won an Oscar nomination as Best Supporting Actress for her performance, but lost to Shirley Jones in Elmer Gantry. In her autobiography, There Really Was a Hollywood (1984), Leigh mentions that Psycho was “an enormous commercial success, but oddly not critically acclaimed in the beginning”. She then adds, “And, for the record, no, I do not take showers.”

The Leigh-Curtis marriage had long been the subject of rumours that the couple fought a lot, even on the sets of their films, and in 1957 Curtis took the advice of Blake Edwards and entered analysis. In 1961 Leigh holidayed without him on the Riviera, but had to return to Los Angeles when her father committed suicide in his real estate office. Although he was having financial problems, he left a note blaming marital difficulties, plus a personal, vitriolic note for his wife, which relatives managed to keep from her.

In March the following year Curtis and Leigh separated legally, and a few days later Leigh was found in a coma on the floor of a hotel bathroom in New York, with an accidental pill overdose blamed. The couple’s California divorce became final in July 1963, but Leigh obtained a quickie divorce in Mexico in September 1962, so that she could marry Robert Brandt, a stockbroker. She kept the children, and Curtis wrote in 1993,

Those girls turned out wonderfully, and Janet deserves most of the credit for that . . . She’s a very fine and very gentle and very sensitive woman, and I admire her.

Leigh gave one of her most accomplished performances in The Manchurian Candidate (1962), that of the enigmatic Rosie, who meets a troubled serviceman (Frank Sinatra) during a train journey and falls in love with him in the course of a cryptic conversation:

Rosie was one of my most difficult roles, not in length, but in content. The character was plunked down in the middle of the script, with no apparent connection to anyone, transmitting non sequiturs while sending meaningful rays through her eyes.

A brilliant study of brainwashing and political chicanery, The Manchurian Candidate, in the famous words of George Axelrod, who adapted Richard Condon’s novel, “went from failure to classic without ever passing through success”.

Leigh played another Rosie in the musical Bye Bye Birdie (1963). In the original Broadway show that part had been the leading one, played by Chita Rivera, but the film was heavily adapted to showcase the studio’s new contractee (and protégée of the director George Sidney) Ann-Margret.

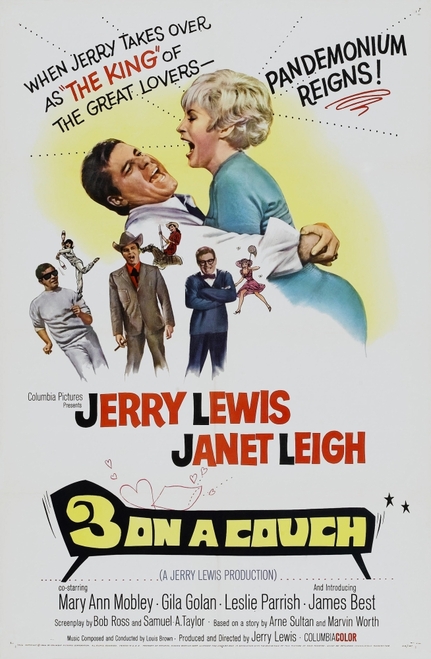

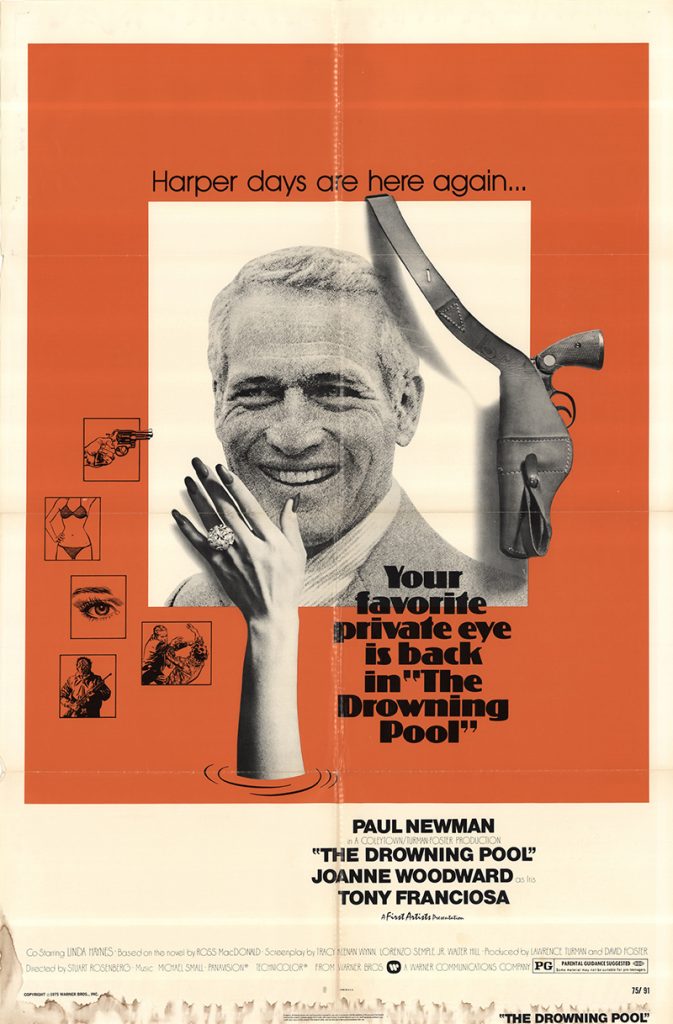

After she appeared in the comedy Wives and Lovers (1963) with her old pal Van Johnson, Leigh’s screen roles became more sporadic, though her fine performance as the ex-wife of private eye Paul Newman in the thriller Harper (1966) was lauded as one of the best things in the film.

She made her Broadway début starring with Jack Cassidy in Bob Barry’s thriller Murder Among Friends (1975) and she worked regularly on television. In 1966 she appeared in two episodes of The Man From U.N.C.L.E. which were released in Europe as a feature film, The Spy in the Green Hat. She was a guest star on such series as Love Boat and Murder, She Wrote, and in 1975 she starred in an unsettling Columbo episode entitled “Forgotten Lady”, in which she played an ageing, reclusive movie star constantly watching one of her old films – clips from Walkin’ My Baby Back Home. She appeared with her daughter Jamie Lee Curtis in John Carpenter’s ghost story The Fog (1980), and more recently had a supporting role in Steve Miner’s Halloween H20: 20 Years Later (1998), which starred Jamie in the role she had created in the original Halloween(1978).

A lifelong Democrat, Leigh was an active political campaigner in the 1960s, particularly for Adlai Stevenson and then the Kennedys, with whom she became good friends. In 1964 President Lyndon Johnson asked her to be ambassador to Finland, but she felt it was too early in her marriage to contemplate separation. For years she worked tirelessly for the charity Share (Share Happiness and Reap Endlessly).

Tom Vallance

The above “Guardian” obituary can also be accessed online here.