Kay Walsh was born in 1911 in Chelsea, London. She made her film debut in 1934 in “How’s Chances”.She was at one time married to the famed director David Lean and was featured in his films – “In Which We Serve”, “This Happy Breed” and “Oliver Twist” as ‘Nancy’. She also appeared opposite Alec Guinness in “The Horse’s Mouth” and “Tunes of Glory”in 1958 and 1960. She died at the age of 93 in 2004.

Tm Vallance’s “Independent” obituary:

A former chorus girl who became a popular screen player in the Thirties, Kay Walsh was leading lady to George Formby in two of the singer/comedian’s hit films. She found most recognition, though, when she had roles in two of the biggest successes of the Forties, In Which We Serve and This Happy Breed.

Kathleen Walsh (Kay Walsh), actress: born London 27 August 1911; married 1940 David Lean (marriage dissolved 1949), second Dr Elliott Jaques (died 2003; one adopted daughter; marriage dissolved); died London 16 April 2005.

A former chorus girl who became a popular screen player in the Thirties, Kay Walsh was leading lady to George Formby in two of the singer/comedian’s hit films. She found most recognition, though, when she had roles in two of the biggest successes of the Forties, In Which We Serve and This Happy Breed.

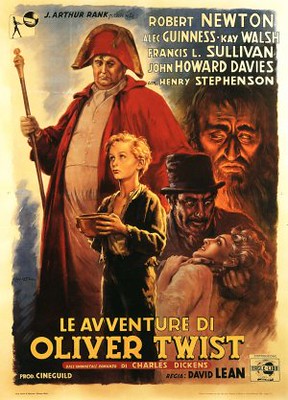

The second of David Lean’s six wives, she encouraged him to become a director, and played Nancy in his version of Oliver Twist. Also a skilled writer, she is credited with devising two of the best-remembered scenes in Lean’s work – the climax of Great Expectations (often cited as better than that conceived by Dickens) and the wordless opening sequence of Oliver Twist. Later she became one of Britain’s finest character actresses, giving outstanding performances in such films as Last Holiday, Encore and Cast a Dark Shadow.

Of Irish stock, she was born in London in 1911 and raised in Pimlico by her grandmother. Although her family was not theatrical, she told the historian Brian McFarlane,

I can’t remember a time when I didn’t dance. My first memory of a public performance was darting into Church Street, Chelsea, and dancing to a barrel organ, aged three.

She was a chorus dancer in revue before making her screen début with a small part in the musical How’s Chances? (1934), then played a leading role in the minor comedy Get Your Man (1934), the first of several “B” movies that displayed her fresh blonde beauty and spirited playing. She remembered these early films with mixed emotions –

Affection because of such warm-hearted old pros as Sandy Powell, Will Fyffe and Ernie Lotinga. Fear, because of having broken out of the chorus at a time of appalling unemployment and presenting myself as an actress. I had had no training and dreaded being rumbled.

In 1936, while filming The Secret of Stamboul, she met Lean, then a fledgling editor who was cutting the Elisabeth Bergner vehicle Dreaming Lips (1937). The pair were soon in love, and Walsh broke off her engagement to Pownell Pellew, later ninth Viscount Exmouth, and began living with Lean. In December 1936, she was appearing in the play The Melody That Got Lost at the Embassy Theatre when she was seen by the Ealing producer Basil Dean, whose wife Victoria Hopper was in the show.

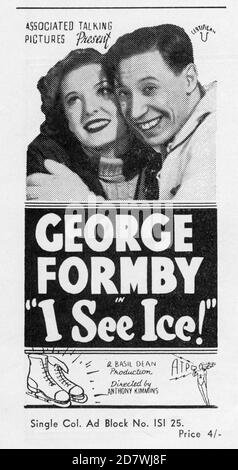

Dean gave her a year’s contract and cast her in her two movies with Formby, Keep Fit (1937) and I See Ice (1938). Walsh described the films as “high-flying compared to the ‘fit-up’ quickies I had been doing”, but she was unhappy at Ealing. She told Lean’s biographer Kevin Brownlow,

I never suffered so much in my life as I did at that studio. They were absolute monsters, and everyone assumed I was Basil Dean’s girlfriend. They were all freemasons and they would never give David a job because he had the wrong handshake.

Although her relationship with Lean, whom she married in 1940, was constantly subject to his infidelities, Walsh recalled their early days fondly:

We worked all day and danced all night and slept through the weekend, waking late on Sunday to make love, to read the Sunday papers and to breakfast on eggs and bacon. And, of course, we went out to a film. We were asked everywhere – we were an attractive couple, we enjoyed life enormously.

When Lean edited Anthony Asquith’s screen version of Pygmalion (1939), Walsh wrote additional dialogue for the film with such skill that, allegedly, Shaw himself never noticed.

Her film roles continued to be in lesser “quota quickies” until she was cast in Noël Coward’s In Which We Serve (1942). She had tested, unsuccessfully, for a role in Leslie Howard’s The First of the Few, but Coward saw the test and thought she had “a nice, mousy quality” perfect for the role of the wife of an Able Seaman (John Mills). Particularly moving was the scene in which she receives a telegram informing her that her husband is one of the survivors of a sunken destroyer. After joyfully shouting the news to her mother, she dissolves into tears. “Kay’s great strength is her reality,” Mills said. “You can hardly believe she is acting; when the camera turned over she just did it.” It was Walsh who persuaded Lean, who was editing the film, to ask for co-director credit with Coward, who eventually agreed. Walsh and Coward got along well, though privately he derided her strong left-wing views, calling her “Red Emma”.

Walsh had an even better role in Lean’s first film as solo director, This Happy Breed (1944), based on Coward’s play. She played Queenie, the erring daughter dissatisfied with working-class life, who leaves home during the night to be with a married man. The scene in which, years later, she returns home, was exquisitely underplayed by Walsh and Celia Johnson, as her mother. “The only difference between Queenie and me was that I would never have given in, never have gone back home.”

She was given a writing credit on Lean’s Great Expectations (1946), her major contribution being the dénouement, completely different from that of Dickens. Estella’s transformation into a second Miss Havisham, and Pip’s throwing open the doors and curtains to let in the light, is generally considered superior to the original ending.

Walsh’s next film as an actress was the comedy-fantasy Vice Versa (1947), Anthony Newley’s first feature film:

I went to the first day rushes, then telephoned David at Pinewood, where he was doing dreadful things in the make-up room to Alfie Bass’s face (to test him for the Artful Dodger). I said, “I’ve got your Dodger.”

Walsh played Nancy in Lean’s Oliver Twist (1948), a performance she herself disliked – she wanted to look dirtier and “more damaged” than Lean would allow her.

She was much prouder of having conceived the film’s haunting opening sequence. Dickens’s novel starts with a matter-of-fact statement of Oliver’s birth, and the film-makers were so desperate to find an effective way of beginning the film that there had even been a competition held at Pinewood:

Finally, I said to David, “Look, I’ve got a couple of pages here I’ve written in an exercise book. Have a look at it.”

She had scribbled a detailed description of a storm, a girl in labour painfully climbing a hill to reach a source of light, and pulling on a bell as she sinks down and the camera goes up to a sign saying, “Workhouse”. A baby’s cry is heard and Oliver Twist is born. Although the film initially received mixed reviews, all agreed that the opening sequence, filmed as Walsh had described, was masterly.

Lean and Walsh were divorced in 1949, Walsh citing his adultery with the actress Ann Todd, who became Lean’s next muse. Later Walsh married Dr Elliott Jaques, a leading psychologist who coined the phrase “mid-life crisis”, and in 1956 they adopted a baby daughter, Gemma.

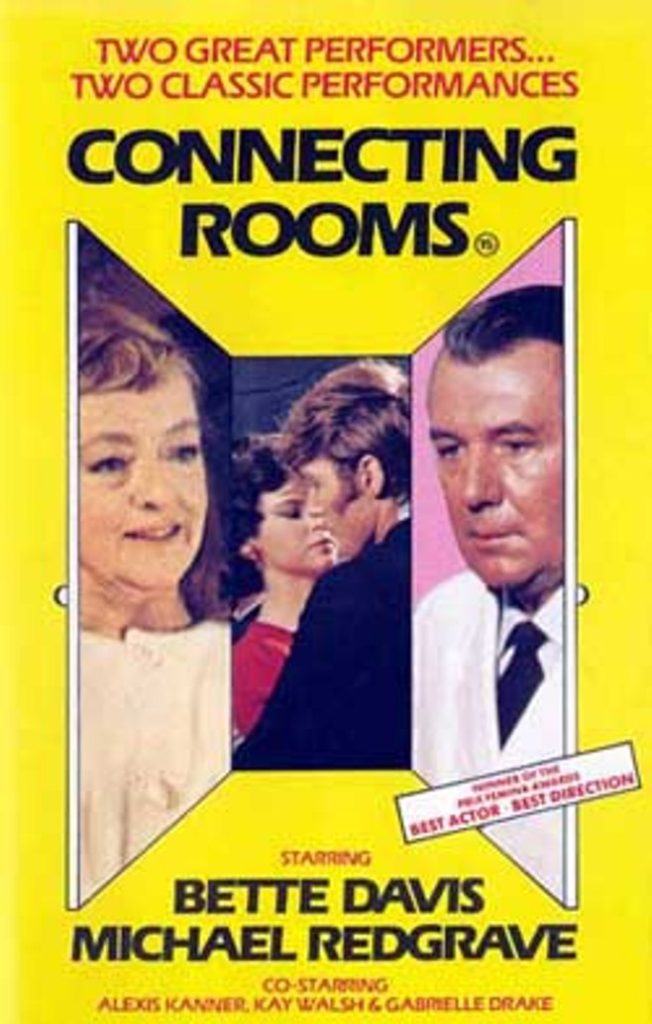

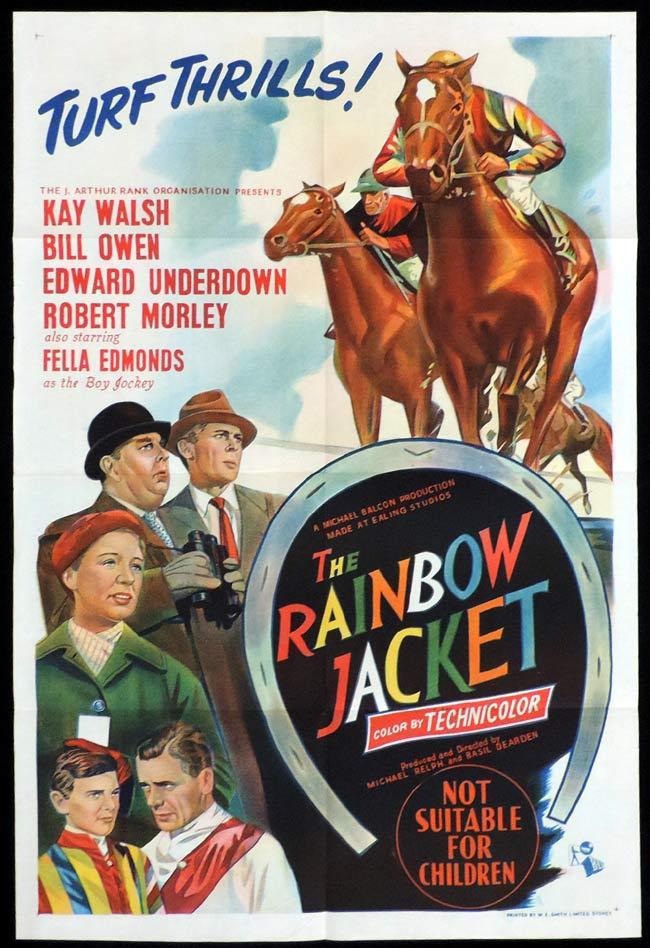

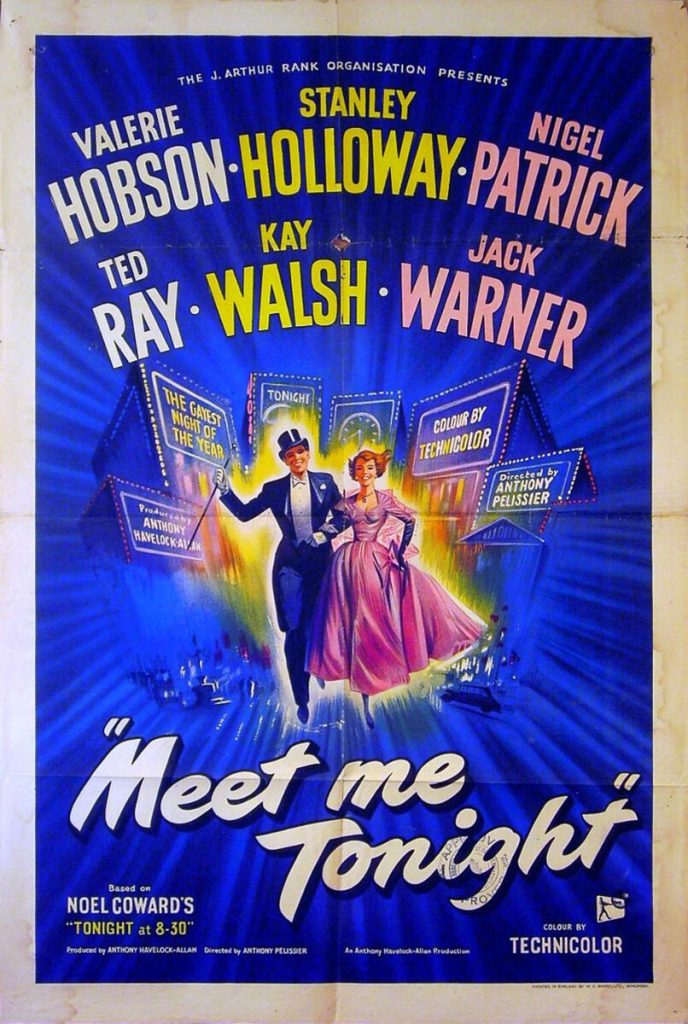

Walsh spent the next decades as a respected character actress, creating a gallery of memorable portraits. She had a good role in Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright (1950), which she remembered primarily for “watching Marlene Dietrich tuck into a steak-and-kidney pudding in the canteen”. She was a sympathetic housekeeper in Last Holiday (1950) with Alec Guinness, and in another Coward adaptation, Meet Me Tonight (1951), portrayed part of a music-hall act in the “Red Peppers” sequence. Her partner was Ted Ray, “the most lovable actor I ever worked with”.

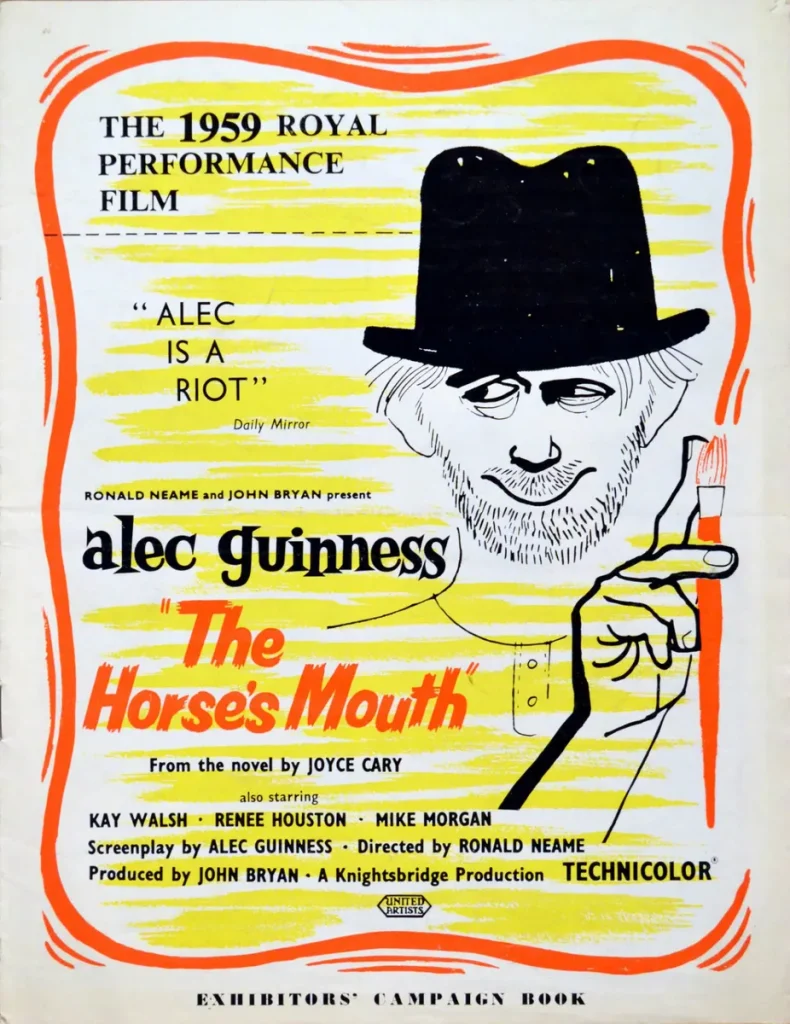

She was the frustrated wife of a vicar in Lease of Life (1954), and in The Horse’s Mouth (1956), again with Alec Guinness, she had her favourite role, as the barmaid. She enjoyed cooking for Guinness, his family, and other friends, and she was also an enthusiastic gardener and renovator of old properties.

Her last film was Night Crossing (1992), based on the true story of a family who escaped from East to West Berlin by hot-air balloon.

Tom Vallance

The above “Independent” obituary can also be accessed online here.