KIERON MOORE OBITUARY IN “THE GUARDIAN” IN 2007.

Kieron Moore was born in 1924 in Skibbereen, Co Cork. He was educated in Dublin and after college, he joined the Abbey Theatre. He made over 50 films and appeared opposite Vivien Leigh in “Anna Karenina” in 1948. He went to Hollywood and made “Ten Tall Men” with Burt Lancaster and “David and Bathsheba” with Gregory Peck and Susan Hayward. He returned to Britain and continued his career there in such films as “Recoil” and “Blue Peter”. In 1959 he returned to Hollywood to make “Darby O’Gill and the Little People” for Walt Disney. In the 1970’s he retired from acting and became editor of “The Universe”, a Catholic newspaper. He died in France in 2007.

The “Guardian” obituary by Mark Lawson:

Kieron O’Hanrahan, who has died aged 82, knew that he would be most remembered as “the actor Kieron Moore”, for roles including Vronsky opposite Vivien Leigh in Anna Karenina (1947) and a bank robber in The League of Gentlemen (1960), but he was never fully satisfied by acting and spent at least the last 30 years of his life in retreat from the profession, working for the Catholic overseas aid agency Cafod and the Catholic newspaper The Universe. Few movie stars end their lives, as Kieron did, visiting the sick in hospital in France. He had retired there in the 90s and, in his latter years, this would have been his idea of a perfect final scene.

The acting had, anyway, unexpectedly overtaken a man who, from his birth on a farm in Skibbereen, County Cork, seemed most destined to be a doctor or writer. Kieron’s father Peadar O’Hannrachain (the Irish version of the family name) wrote books, poetry, journalism and a play, promoting Irish nationalism and the Gaelic League to the extent that he was both jailed and deported (to Herefordshire) by the British.

Kieron was greatly influenced by his father’s experiences and once, on a journalistic assignment to Belfast, refused to speak English to a patrolling British soldier. Only after his funeral did I discover that this incident directly repeated an act of defiance by his father which had been immortalised in an Irish poem. He inherited from this family background a lifelong concern with oppressed or dispossessed people which emerged in two documentaries he wrote and directed for Cafod: Progress of Peoples, shot in Peru, and The Parched Land, filmed in Senegal.

Kieron also drew from his father a passion for Ireland and for writing, although he was never as happy in either as he might have hoped. The first profession he chose was medicine but, after only a few months at University College hospital in Dublin in 1941, his hobby of acting accelerated, and roles in two late plays by the writer Sean O’Casey – Purple Dust and Red Roses for Me – took him to Liverpool and then London, where a movie scout offered a seven-year contract and an anglicised surname.

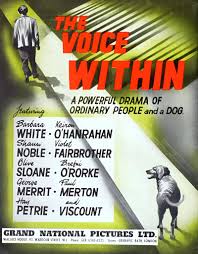

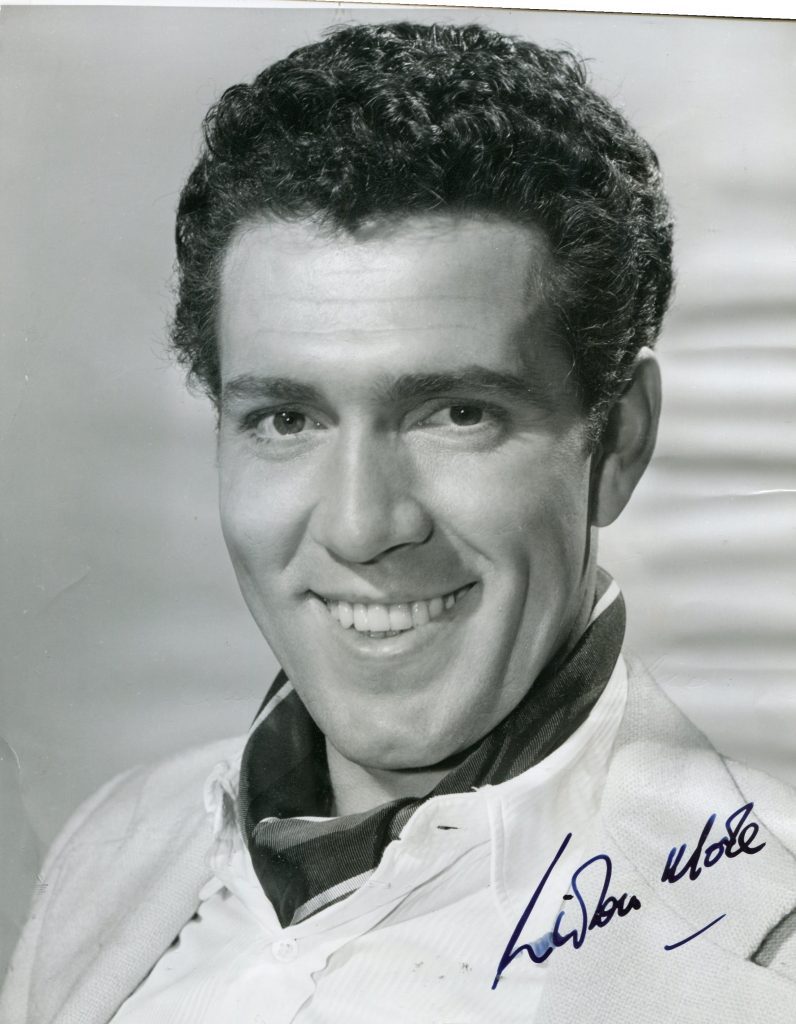

Two leading film encyclopaedias by Ephraim Katz and David Thomson, describe Kieron Moore respectively as “a husky, stern leading man” and “an Irish actor with a hangdog expression”. The latter aspect, if true, possibly reflected the actor’s own uncertainty about his calling, perhaps because he had always felt most at ease speaking Irish on stage rather than English on film. He would later recall his misery before attending the Royal Command Performance of Anna Karenina, knowing that he had been stiff and miscast. He regularly spoke well of only one of his films: The Green Scarf (1954), in which, among a cast including Michael Redgrave and Ann Todd, he played a deaf, dumb and blind author accused of murder. And, while his debut film, The Voice Within (1945), meant little to him professionally, it was of great personal significance: on the set, he met the actor Barbara White, to whom he was married for 59 years.

Kieron’s escape from cinema – and an opportunity to honour his father’s political intensity – came in 1974, when Cafod offered him a six-month sabbatical as an ambassador which stretched to nine years and put him on the other side of the camera. If the documentaries had exposed his writing gene, journalism released it when, in 1983, he joined The Universe, the biggest-selling Catholic newspaper, as associate editor. (Between 1984 and 1986, I worked for him there as reporter, TV critic and feature writer.)

He still fulfilled the cliche of “film-star looks”, with a tennis-court tan and a firm head of hair which betrayed his age only by greying. Had he not retired from acting, he could easily have played Omar Sharif in a biopic. Even when on time, or early for work, he always seemed to enter the office at the run, a tan shoulder bag bulging with copies of the morning papers, annotated on the train from Surrey, and the works of theology and classics of European and Irish literature which usually alternated in his reading, apart from a passion for the spy thrillers of the American writer Charles McCarry. He would frequently spend two days reworking the main editorial, usually choosing as his subject international inequality or injustice.

Kieron sometimes struggled to adjust to the tone of Catholic journalism. Once, when a visiting priest was railing against the free availability of condoms in society, he testified that they were like “washing your feet with your socks on”, not a theological objection previously considered.

His passionate commitment to projects also sometimes caused problems. Once, when he burst into a Universe meeting shouting “the bastards have blown up Middlesbrough Cathedral!”, colleagues assumed that a gruesome act of terrorism had occurred, but the associate editor had simply noticed that the printers had increased the size of an ecclesiastical photograph against his wishes. His entry into journalism coincided with the rise of video recorders, and one sub-editor, after losing a particularly fierce editorial argument, was in the habit of cathartically screening the sequence in The Day of the Triffids (1962), in which Moore’s character is eaten by a plant.

But, if stubbornness existed in him beyond ordinary human levels, so did kindness. One of his aims at The Universe was to humanise the paper’s moral advice column (a sort of “agony nun”) beyond the stern reiterations of Vatican law that had been the previous practice. The God he believed in was demanding, but also forgiving.

He encouraged and championed young writers and was later delighted to see former staff turning up in the national papers or the BBC. It gave him great pleasure that Roger Alton, who he had employed to professionalise page designs, became editor of the Observer.

Kieron was a Catholic of great faith (for much of his life attending mass daily) and, in this respect at least, would have made a good priest, although he would not easily have foregone the pleasures of flesh and family.

He was fiercely proud of his children and pleased that all entered caring professions: his daughter a nun, two of his sons teachers and the other a psychotherapist. They and Barbara survive him.

· Kieron O’Hanrahan (Kieron Moore), actor, journalist, charity worker, born October 5 1924; died July 15 2007For “The Guardian” obituary, please click

DICTIONARY OF IRISH BIOGRPHY

Moore, Kieron (1924–2007), actor and catholic activist, was born Ciarán Ó hAnnracháin in Skibbereen, Co. Cork, on 5 October 1924, one of four sons and two daughters of the Gaelic Leaguer and political activist Peadar Ó hAnnracháin (1873–1965) and his wife Máire Ní Dheasúna (Desmond) (1888–1967) from Kinsale. Peadar Ó hAnnracháin was one of thirteen children of a small farmer in the Skibbereen area. Having learned Irish from a textbook, he became a travelling teacher, writer, and journalist in Irish; his arrest in Abbeyfeale, Co. Limerick, on 10 June 1912 for insisting on giving his name in Irish to a policeman became a cause célèbre. He joined the Irish Volunteers in 1913 and was imprisoned for IRA activities several times between 1916 and 1921. At the time of Ciarán’s birth the Ó hAnnracháin family lived on a small farm that they owned, Peadar supplementing his farming with journalism and a local government job. The farm was sold in 1938 when Peadar took up a civil service position in Dublin. He was the author of numerous books in Irish, including poems, plays, a novel, and memoirs such as Fé bhrat an Chonnartha(1944), an account of his Gaelic League work, and Mar mhaireas é(1953). Ciarán’s siblings included the actress Neasa Ní Annracháin (mother of the broadcaster Doireann Ní Bhriain), Fachtna Ó hAnnracháin (director of music with Radio Éireann), and the harpist Bláithín Ní Annracháin. The family were brought up as Irish-speakers, and a persistent tendency to stiffness in Moore’s vocal delivery on film reflected a preference for Irish. Moore’s cultural sophistication (as an adult he read four languages and had a wide-ranging love of literature) grew from the heritage of his father, and in later years he campaigned on behalf of poor farmers in developing countries whose living conditions resembled those of his ancestors.

Moore was educated at Coláiste Mhuire, Dublin, and studied medicine at UCD for a few months in 1941 before dropping out to join the Abbey Players (having appeared as an amateur in two Irish-language productions in the Peacock theatre). His lead in an Abbey production of the mediaeval mystery play ‘Everyman’ was praised, and in 1943 he moved to England to pursue an acting career. He initially attracted critical acclaim by playing Heathcliff in a stage adaptation of ‘Wuthering Heights’ at the Richmond theatre in Surrey (reprising the role in a 1948 BBC TV production), followed by the role of Ayamonn Bredon in ‘Red roses for me’, the West End hit by Sean O’Casey (qv). (Moore had previously appeared in a Liverpool production of O’Casey’s ‘Purple dust’.) His height and dark good looks fitted the image of the romantic hero

Moore married (1947) the actress Barbara White; they had three sons and one daughter (who became a nun), all of whom used the name ‘O’Hanrahan’ rather than ‘Moore’. Moore frequently expressed pride that his children had all entered the caring professions. In 1994 he retired to the village of Saint-Georges-Antignac in the Charente-Maritime department of France, chosen because of its remoteness from the usual Anglophone expatriate haunts; he joined the local choir and spent part of his time as a volunteer hospital visitor in the nearby town of Jonzac. He died in Jonzac on 15 July 2007, and is buried in Saint-Georges-Antignac. His acting career never fully reflected the deep personal hinterland on which he drew in reading, writing, and social activism, and like the better-known Patrick McGoohan (1928–2009) he was marked by a life experience stretching from the smallholdings of inter-war western Ireland to Hollywood, and held together by commitment to marriage, family, and a personalised catholicism: Kieron Moore was never allowed to displace Ciarán Ó hAnnracháin.