Beautiful Morag Hood was born in Glasgow in 1942. She began her career as a TV presenter and was one of the first people to interview for TV, the Beatles in 1963. She had a celebrated stage career including a breathtaking ‘Stella’ in “A Streetcar Named Desire” in London in 1974 with Claire Bloom and Martin Shaw. Two years earlier she played ‘Natasha’ in the television adaptation of “War and Peace” with Anthony Hopkins as ‘Pierre’. She died in London in 2002.

Her obituary from “The Scotsman”:

TWO months ago, Morag Hood was visited in the London hospice where she spent her final months by her close friend, the actor Sian Phillips. Morag was not expected to live for many more days. Indeed, the medical team caring for her was convinced she was drifting into a coma. Suddenly, Phillips reported, Morag opened her eyes and said softly: “I think that was the dress rehearsal.”

It was a remark that was typical of Morag Hood, who was a remarkable actress but an even more remarkable woman. She had beaten cancer once – more than a decade ago – and when it cruelly returned she faced it with grace and immense courage, surrounded by loving family and an army of friends from film, theatre, television and rock music – Sting and his wife, Trudi Styler, were devoted to her.

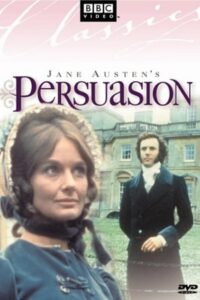

A generation of men grew up besotted with the blonde actress with doll-like proportions and porcelain skin. Her luminous performance in the Seventies TV version of War and Peace had a hypnotic effect on half the male population. She had won the part of Natasha after more than 1,000 hopefuls were auditioned for it and she turned in a wonderful interpretation, although she had no formal acting training.

Morag’s father was master of works for the company that owned most of Glasgow’s cinemas and theatres, so she was enchanted by the world of make-believe from an early age. In her teens, she also hosted, with Paul Young, a weekly current affairs programme, Roundup, on STV

The youthful Anthony Hopkins was her leading man in the Tolstoy, although over the years she acted with everyone from John Gielgud and Paul Scofield to Hollywood’s Robert Duvall. She also worked extensively at the National Theatre and was a favourite with directors such as Peter Hall, Bill Bryden and Michael Bogdanov.

Her diminutive stature and exquisite bone structure were deceiving. For she was a powerful actor with enormous presence, both on stage and screen, a sort of steel magnolia. In the Nineties, for instance, she gave a brittle-as-glass performance as the menopausal wife of a serial philanderer (Trevor Eve) in Andrea Newman’s gripping TV serial, A Sense of Guilt. And, despite the fact that the symptoms of her final illness had already begun to manifest themselves, one of her finest stage performances was in Torben Betts’s dark drama, A Listening Heaven, at Edinburgh’s Royal Lyceum Theatre in 2001. It won her a nomination in last year’s prestigious Barclays Theatre Awards for Best Actress.

She had last been seen at the Royal Lyceum in the world premiere of Stewart Conn’s Clay Bull in 1998, but returned from her north London home the following year to play Robert Duvall’s wife in the film A Shot For Glory. It was a thrill to play opposite a big movie star, she said, but she felt doubly blessed because her character was so well written.

A graduate of Glasgow University, where she read English, French and Economics, Morag loved words and was a champion of new writing. She premiered three plays by the Young Turk of Scottish theatre, David Greig. She was in The Architect and the original production of The Cosmonaut’s Last Message to the Woman He Once Loved in the Soviet Union. In 2000, she played in his trilogy, Victoria, at the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Barbican Theatre.

Acting was her passion, but she was also a dedicated gardener, creating new gardens for friends such as the actors Leslie Phillips and his wife, Angela Scoular, when “resting”.

She approached a part in a TV soap with as much energy and commitment as she did a classic play. The last time I interviewed her, she had just filmed an episode of the TV series Heartbeat, in which she ended up murdered on page 36 of the script. “She was a very interesting woman, so I was sorry she had to come to a sticky end,” she said.

I first interviewed her when she was playing Brian Cox’s wife in The Master Builder in the acclaimed 1993 Edinburgh Royal Lyceum production. She told me then that she was revelling in her middle years. Unlike many actors who bemoan the dearth of roles for women of a certain age, Morag believed she only began to flourish as a performer when she chalked up her half century. As a talented writer, she felt theatre, film and especially television, should reflect older women’s lives.

To this end, in recent years she was juggling at least four projects. She was working on a film script based on the family story of her actor friend Jane Gurnett and a major documentary with Elaine C Smith. The author of several well-received documentaries, including one on forgotten women artists such as the Glasgow Girls, Morag lectured about the life of Charlotte Bront, another of her TV “subjects”.

The role of Scottish women like Dr Elsie Inglis at the Front during the First World War had fascinated her since she played a nurse in Bill Bryden’s epic, The Big Picnic, in Glasgow, and she researched the period in depth for a proposed docu-drama. Everything she wrote was about hidden lives, she once remarked. “It’s stuff that has been neglected in the past that I like pulling into the present.”

Although she never married or had children, Morag had three long love affairs. “They were true marriages,” she said. She also found her own spiritual path and often spent time on an ashram in India.

I was privileged to count Morag Hood as my friend and my abiding memory of her will be of lots of giggles and of juddering around the Edinburgh Fringe together in her battered Fiat Panda, which we always managed to find again. No mean feat, because she famously once parked one of her crumbling cars somewhere, but could never ever remember where she had left it.

The “Scotsman” obituary can be accessed online here.