Norman Rodway was born in Dublin in 1929. He made his stage debut in 1953 at the Cork Opera House in “The Seventh Step”. His films include “This Other Eden” in 1959, “Four in the Morning”, “Chimes at Midnight” and “The Penthouse”. He died in 2001.

Dennis Barker’s “Guardian” obituary:

In the opinion of a new friend, the actor Norman Rodway, who has died aged 72 following a stroke, was “a bit of a rascal in the nicest possible way – the only little boy I know who is over 70”.

On stage, on television and on the big screen, he was often a professional Irishman, one who could play the gnarled Captain Jack Boyle in Sean O’Casey’s Juno And The Paycock, alongside Judi Dench, without anyone questioning his Irishness. Indeed, one of his first parts in London was the hero of James Joyce’s Stephen D, a pot-pourri of Joyce’s writings in which Rodway was well able to suggest the tensions existing in a Catholic Irishman half wanting to break free of his past.

In fact, he was born neither Catholic nor Irish, but was the son of a middle-class English father whose firm happened to send him to a post in Dublin just prior to his birth. His “Irishness” could nevertheless sometimes complicate things for his agent Scott Marshall when finding him non-Irish parts.

At Dublin high school, the youthful Rodway made his debut in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Iolanthe, singing soprano. The following year, he appeared in a leading part in The Gondoliers, as a dressed-to-kill girl in black wig, crimson lipstick, heavy mascara and a 44-inch bust. This brought him his first encore at the end of the first act. By now, he knew that he wanted the stage to be his career.

Any impression of effeminacy that his soprano roles might have fostered at school was undercut by the fact that Rodway also starred as cricket captain, with top batting and bowling averages. His father had two private enthusiasms – cricket and opera – and had seen to it that his son was liberally exposed to both. At the age of nine, Rodway remembered practising his batting strokes against his father’s bowling in their back garden at Malahide, after which they went to his father’s study to listen to opera on the radio.

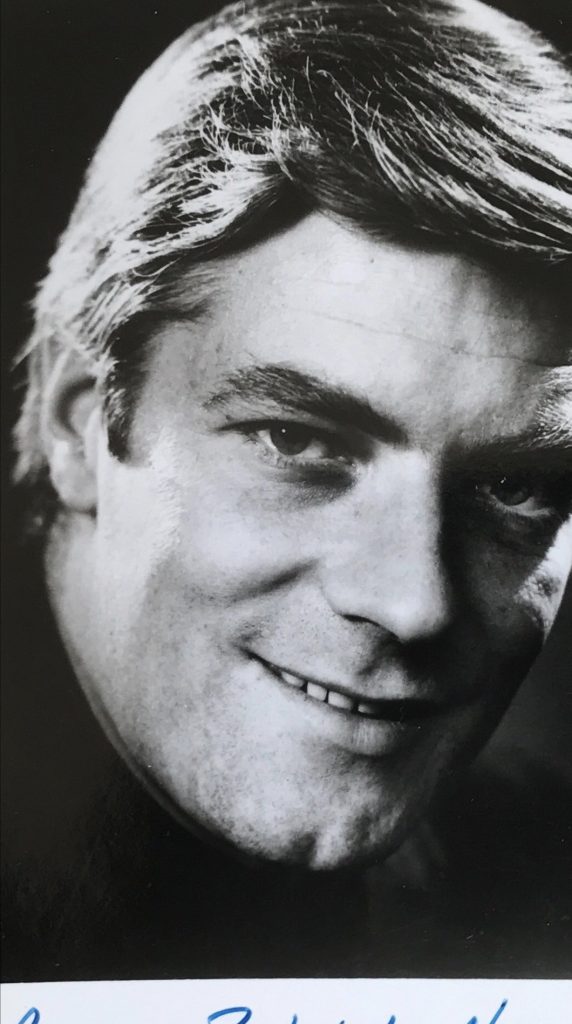

Cricket, and any branch of theatre, were to remain his enthusiasms, and his short, stocky frame, lantern jaw and piercing eyes were to make him especially adept at playing rascally or threatening parts, from Richard III, for the Royal Shakespeare Company, to Hitler, in the television psycho-drama The Empty Mirror, in which the dictator survived the war and had to face his crimes.

After winning a scholarship to Trinity College, Dublin, where he took an honours degree in classics, Rodway spent a year teaching, a year lecturing, and even a very short time in the cost accountancy department of Guinness. While enduring these mundane ways of earning a living, he was also acting on a semi-professional basis in Dublin, where the line between professional and amateur tended to be more flexible than in Britain.

In 1953, he appeared in the first production by the newly-formed Globe Theatre Company, and was soon running the group with Jack McGowran and Godfrey Quigley, until they hit the financial skids eight years later. Fortunately, he had not severed all contact with London, where both his parents came from. He appeared in a Royal Court Theatre production of Sean O’Casey’s Cock-A-Doodle Dandy and, in 1963, settled in the capital permanently.

New things were happening in British theatre, and one of the people making them happen was John Neville, who ran the new Nottingham Playhouse and who invited Rodway to appear as Lopakin in his production of The Cherry Orchard. Three years later, Rodway joined the Royal Shakespeare Company, the beginning of a long association that saw his larger-than-life persona being used to best advantage.

After seeing the Laurence Olivier film version of Richard III 10 times, and watching Ian Holm on stage five times, Rodway took the leading role in Terry Hands’s 1970 production with such force that one critic commented that his performance, crowning a recent series of grotesque roles, was directly satanic – a spirit of evil driven on his course by self-loathing and, in particular, by loathing for his own body. “He is as ridiculous as he is villainous, and never more so than when he claps an outsize crown on that shaven bullet head.”

Rodway’s flare for arresting effects was perhaps better suited to the stage than to the cinema, but he appeared in many varying roles on the big screen, and even survived playing Hotspur in Chimes At Midnight (1966), in which Orson Welles both directed and played a Falstaff extracted from several Shakespeare plays. Rodway noticed that as shooting went on, Welles’s part got bigger and bigger, while his own got smaller and smaller. As always, Welles also periodically ran out of money, so that at one stage the film was impounded in a Spanish bank vault as a security for a debt.

The following year, as if paying tribute to his own stamina, Rodway appeared with Welles again, this time in I’ll Never Forget What’s ‘Is Name, with director Michael Winner on hand to prune the less acceptable parts of Welles’s ego. A romantic comedy was not Rodway’s main forte, but he also appeared in a supporting role to Suzy Kendall in Peter Collinson’s The Penthouse, another 60s cult film.

On television, his range was wider than his physical limitations. Apart from playing the dominant role of Hitler in The Empty Mirror, where his flare for outsize presence and gesture made the dictator like something out of a strobe-lit nightmare, he appeared in a number of televised Shakespeare plays, and was also a popular guest for one-off appearances in favourite series. These included Jeeves And Wooster, Miss Marple, Rumpole Of The Bailey, The Protectors and Inspector Morse. He made more than 300 broadcasts for BBC radio, including Brian Friel’s The Faith Healer, for which he won the 1980 Pye Radio Award for Best Actor.

Rodway was married four times, first to the actress Pauline Delany, then to the casting director Mary Sellway, and thirdly to the photographer Sarah Fitzgerald, by whom he had a daughter Bianca. She survives him, as does his fourth wife, Jane, whom he married in 1991.

Michael Pennington writes: Norman Rodway’s laughter came in two registers – a full-throated chuckle and a sort of incredulous trill. It was somehow to do with his conviction that everything was a form of comedy, including tragedy; nothing was more serious than the first, nothing more foolish than the second.

In the theatre, you sometimes catch up with your heroes. The Stephen D that arrived with a bang from Dublin in 1963 was an awesome buccaneer who would become my friend, and I learned that this red-blooded manner hid a spirit almost too delicate and fine – kind and anxious and always on your side. A first-class classical scholar, a pianist who could name every Köchel number in Mozart (but loved his Schubert even better), he was completely unpredictable in his judgment of a performance.

When he was ill and immobilised, his eyes locked on to you and followed you round the room, undeceived at the end, like the Lear he should have played. One of the very greatest radio performers, a Shakespearian to the heart, and a great spirit gone. I hope he’s laughing his laugh.

Norman Rodway, actor, born February 7 1929; died March 13 2001

For obituary on Norman Rodway, please click here.

Dictionary of Irish Biography

Rodway, Norman John Frank (1929–2001), actor and theatre producer, was born 7 February 1929 in Dublin, son of Frank Rodway, manager of a shipping agency, and Lilian Rodway (née Moyles). The couple had recently moved to Dublin from London. They settled in Malahide, north of Dublin, where Norman attended St Andrew’s Church of Ireland national school before proceeding to the High School, Harcourt St., and to TCD on a scholarship. An excellent student, he graduated with first-class honours in classics in 1950. After lecturing briefly, he began working for Guinness’s brewery, while taking an accountancy degree. Stage-struck since school, he made his debut in the Cork Opera House in May 1953 as Mannion in ‘The seventh step’, and thereafter took on roles in Barry Cassin’s and Nora Lever’s 37 Theatre Club, where he met his first wife, the actress Pauline Delany, whom he married in 1954. That year he was made director of the recently established avant-garde Globe Theatre Company at the Gas Company Theatre, Dún Laoghaire, and the following year he turned professional actor.

Never an Abbey actor, he appeared frequently at the Gaiety, the Gate, and the Olympia and took leading roles in Christopher Isherwood’s ‘I am a camera’ (1956), and John Osborne’s ‘Epitaph for George Dillon’ (1959). As the Globe’s director, he accepted a play by the newcomer Hugh Leonard, ‘Madigan’s Lock’ (turned down by the Abbey), and played the lead when it opened at the Gate Theatre (where the Globe moved) in summer 1958. Leonard described Rodway as ‘modelled on Olivier, using the same vocal tricks, among them the sudden inflection that informed a moment of villainy with a subtext of sardonic humour’ (Sunday Independent, 18 March 2001). He played the Citizen in Leonard’s ‘A walk on the water’ for the 1959 Dublin Theatre Festival; it was the Globe’s last performance – the theatre shut down shortly afterwards – and Rodway went into partnership with Phyllis Ryan to found Gemini Productions, which produced William Gibson’s ‘Two for the seesaw’, Tom Murphy’s ‘Whistle in the dark’, and Leonard’s ‘The passion of Peter Ginty’, all featuring Rodway.

He scored his first major success as the title role in Leonard’s adaptation from James Joyce (qv), ‘Stephen D.’, which opened at the Gate in the 1962 Dublin Theatre Festival. When the play transferred to the West End, Peter O’Toole offered to play Stephen, but Leonard held out for Rodway, who received rave reviews. However, Leonard noted that T. P. McKenna, who came on in the second act as Cranly, always stole the play: ‘Rodway had every quality except the important one: star quality’ (Sunday Independent, 18 March 2001). For the 1964 Dublin Theatre Festival, Gemini Productions put on Leonard’s new play ‘The poker session’. It transferred to the West End and was not a success, but Rodway, who appeared as the assassin Billy Beavis, was much in demand; he moved to London and in 1966 was taken on by the Royal Shakespeare Company, with which he remained, on and off, till 1980. He rarely returned to Ireland but appeared in the 1971 Dublin theatre festival in Leonard’s irreverent farce ‘The Patrick Pearse Motel’.

In the 1966 RSC season he doubled the roles of Hotspur and Pistol in ‘Henry IV’, and played Feste in ‘Twelfth night’ and Spurio in Tourneur’s ‘The revenger’s tragedy’. Critics praised his intelligence and strong stage presence, helped by his big-boned, athletic physique and a head crowned with thick auburn hair. When he played Mercutio the following season, The Times wrote: ‘Norman Rodway unleashes his full range of grotesque comedy, orchestrating the fantastic tirades with rich pantomime and exhaustively milking the text for bawdy’ (14 September 1967). His first leading role for the RSC as Richard III in Terry Hands’s 1970 production was considered less successful. He generally excelled in supporting roles – particularly comic and Slavic parts. He played his first Chekhov in the Nottingham Playhouse’s ‘The cherry orchard’ in 1965 and was memorable in the RSC’s Gorky and Chekhov seasons (1974 and 1976). A natural choice for Irish roles on the London stage, he was notable as Sir George Thunder in ‘Wild oats’ (1977) by John O’Keeffe (qv), and outstanding as Captain Boyle to Judi Dench’s Juno in Trevor Nunn’s acclaimed production of Sean O’Casey‘s (qv) ‘Juno and the Paycock’ (Aldwych, 1980). The Times praised him for eschewing obvious comedy and cheap laughs.

Rodway had around forty film credits – generally small roles in low-budget films. His early films include This other Eden (1959), Nigel Patrick’s Johnny Nobody (1960), and Anthony Havelock-Allan’s The quare fellow (1962), all set and shot in Ireland. His appearance as Hotspur in Orson Welles’ Chimes at midnight(1966) persuaded Peter Hall to offer him that part in the RSC, and he starred opposite Judi Dench in Four in the morning (1966) which was given the award for best film at the Locarno Film Festival. Later in life, he playerd Hitler in the surreal film The empty mirror (1999).

His television career was more impressive; he had strong supporting roles in numerous series such as ‘Inspector Morse’, ‘Reilly: ace of spies’, ‘Rumpole of the Bailey’, ‘The professionals’, and ‘As time goes by’, and was a stalwart in Jonathan Miller’s productions of Shakespeare for the BBC. However, his greatest success off the stage was on radio, where his rich, expressive voice was much in demand. He appeared in 300 programmes and won a Pye award (the industry’s equivalent of an Oscar) for Brian Friel’s quartet of monologues, ‘Faith healer’, in 1980. His gift for comedy found expression in Alan Melville’s ‘Don’t come into the garden’ (1983) and as Apthorpe in Barry Campbell’s adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Sword of honour (1974). After heart surgery in 1997 he gave up live theatre, and died, after a series of strokes, in Banbury, Oxfordshire, on 13 March 2001.