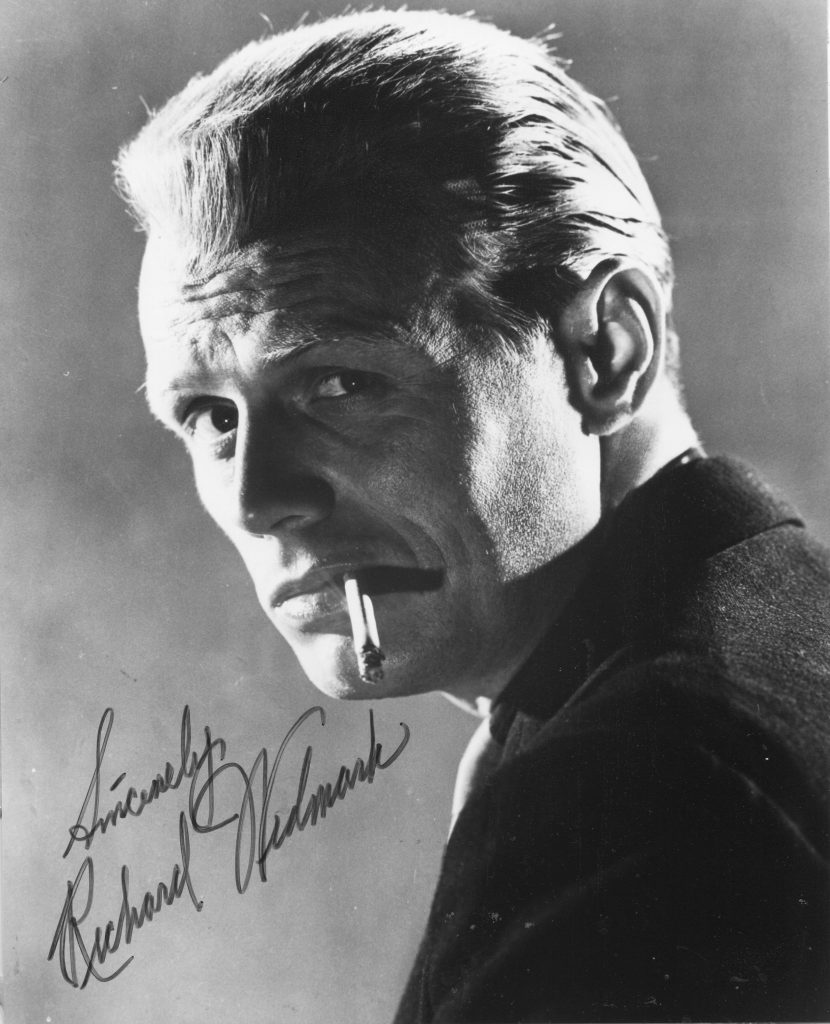

“When Richard Widmark deserted villainy the screen lost one of its best villains. He was never so entertaining as a hero. As a hero, to be blunt, he is second-rate – oh, likeable, full of integrity, conscientious and all of that, but when he is tough and cocky it is a long way after Cagney. When he is jaded, he is way behind Bogart and he has hardly a hint of the bravura that made Errol Flynn so attractive to women. Nor – though he is probably a better actor – does he fill the screen quite so well as Burt or Kirk or Chuck. He is, in a word, self-effacing. His interviews made it clear that this is a man who loves his craft rather than the aura of being a big film star. He was not content to play psychopathic killers throughout his career” – David Shipman in “The Great Movie Stars – The International Years” (1972)

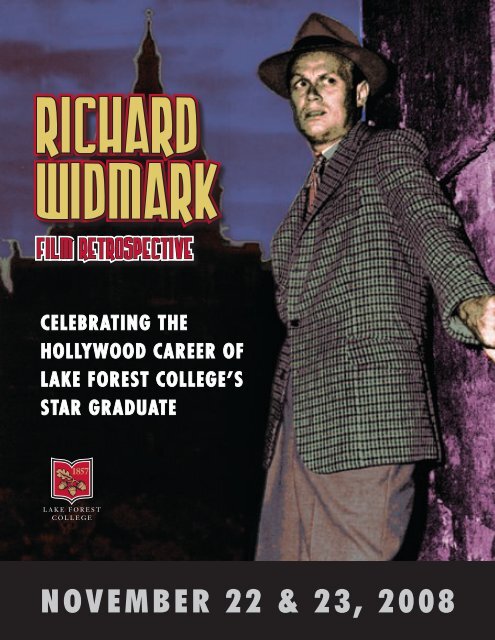

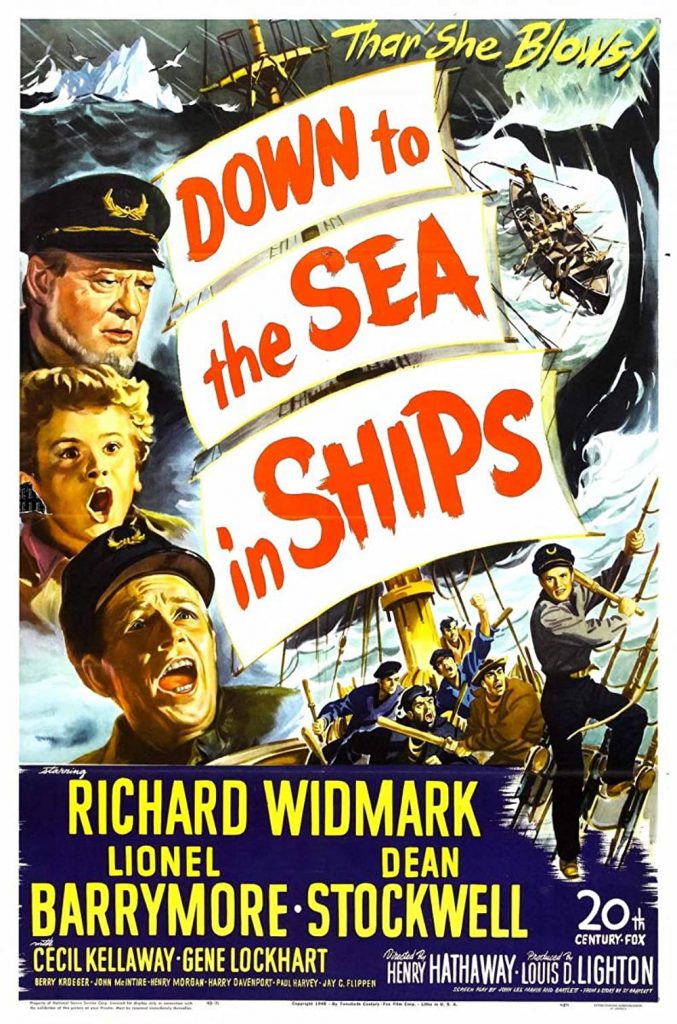

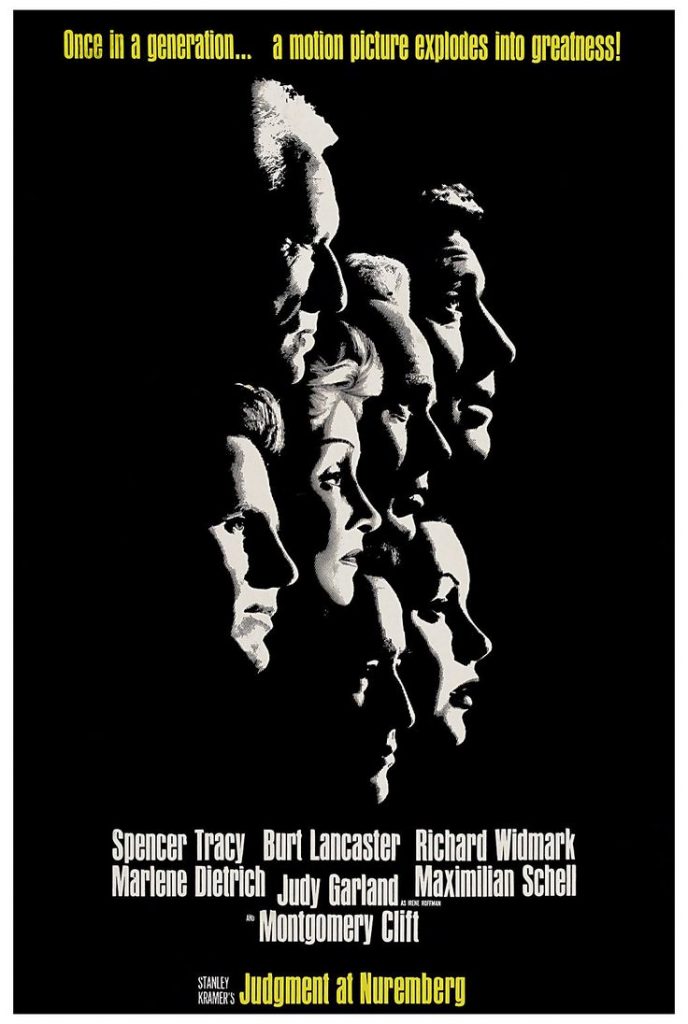

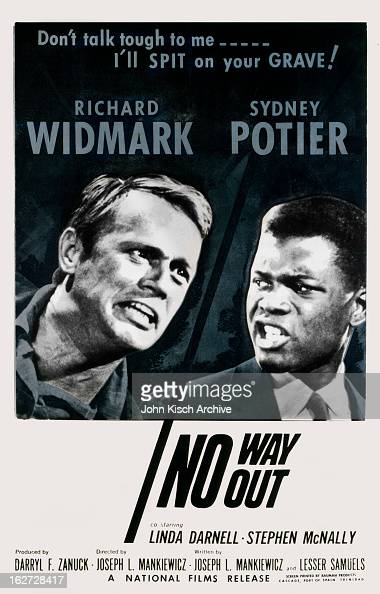

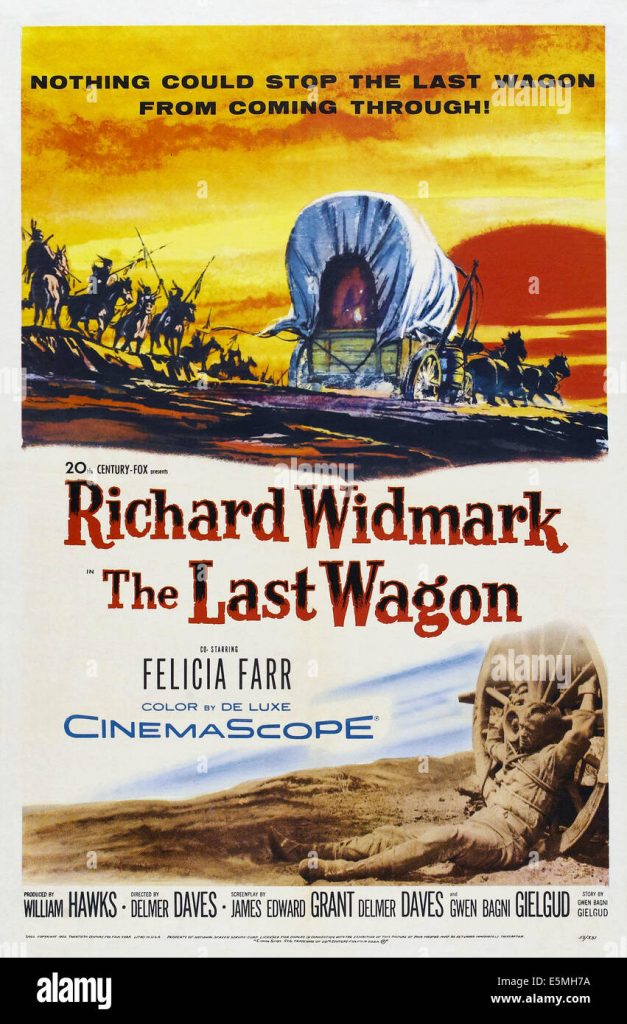

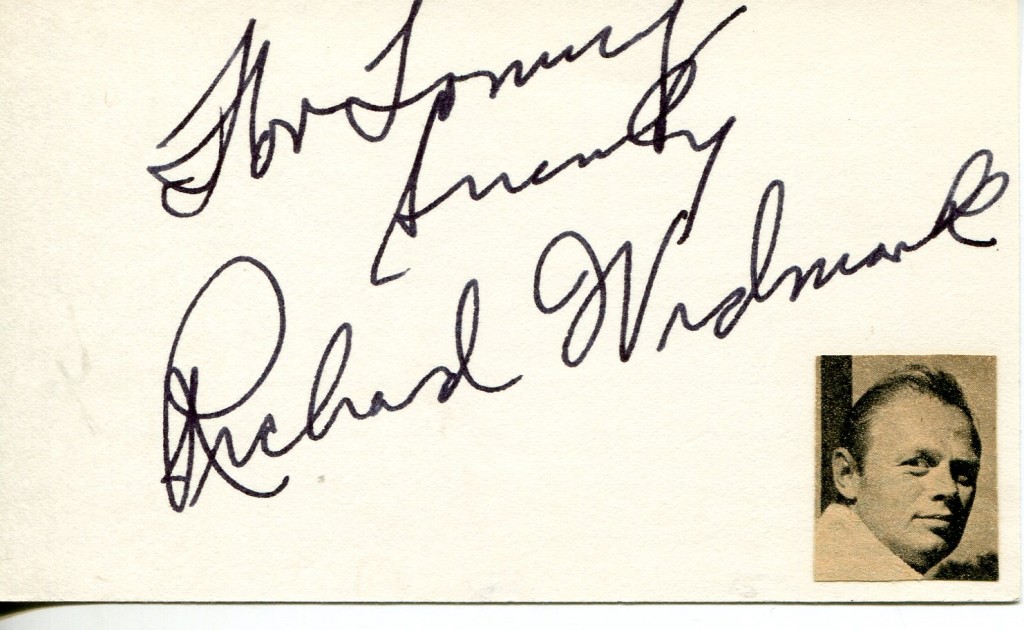

Richard Widmark was one superb actor. He played heroes but he was equally brilliant as villians such as Tommy Udo the giggling psychopath in “Kiss of Death” in 1948 and then in 1951 as the racist thug giving Sidney Poitier a hard time in “No Way Out”. His major movies include “Down To Sea In Ships”, “Yellow Sky”, “The Last Wagon”, “Judgement At Nuremberg” and “Madigan”. He died at the age of 93 in 2008.

Ronald Bergan’s obituary of Richard Widmark in “The Guardian”

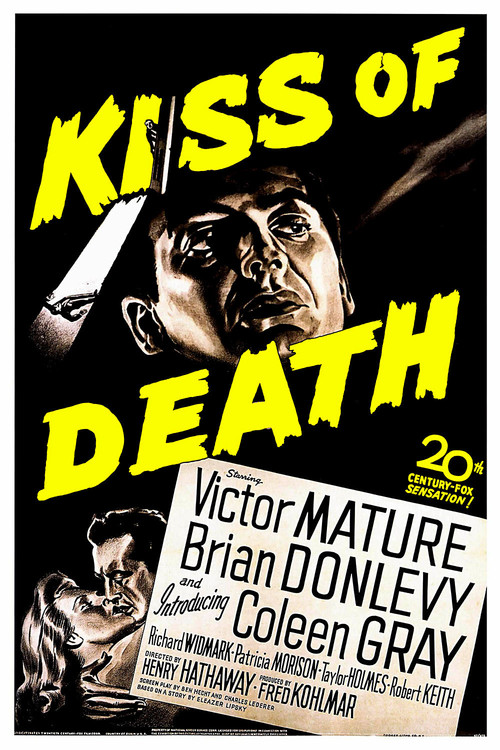

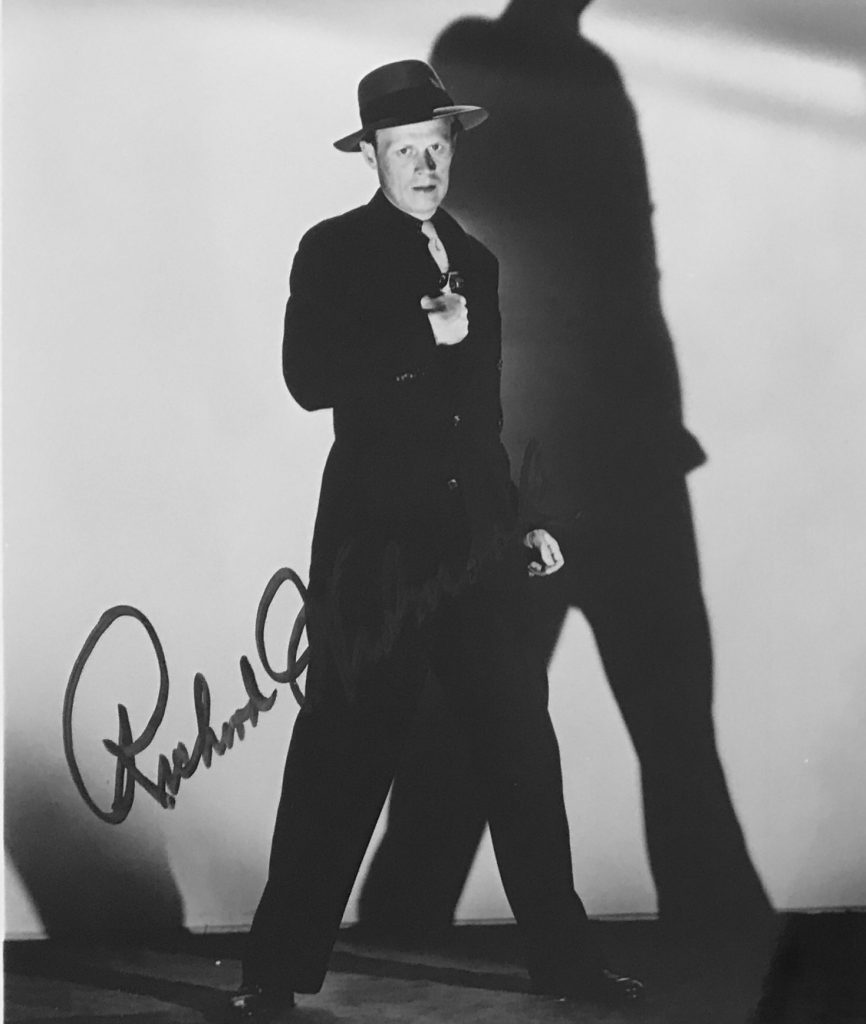

You’re Nick Bianco, aren’t you? You’re a big man. I’m Tommy Udo. Imagine me on this cheap rap – big man like me, picked up just for shoving a guy’s ears off his head. Traffic ticket stuff.” These were the first words uttered on screen by Richard Widmark, who has died aged 93. It was one of the most striking debuts in Hollywood history.

The film was Henry Hathaway’s Kiss of Death (1947), and the nominal stars were Victor Mature and Brian Donlevy. But it was Widmark, in a relatively small part, whom everyone remembered. No matter how far he moved away from Tommy Udo in his long career, even when he played noble characters, that giggling psychopath was always just beneath the surface.

Widmark was born in the farming community of Sunrise, Minnesota, where his Swedish-born father ran the general store. His original ambition was to become a lawyer, so he enrolled at Lake Forest College in Chicago. It was there that he became involved in the dramatic society.

After graduating in 1936, he remained at the college as an instructor in speech and drama. In 1937, while he and a friend were touring Europe on bicycles, they shot a short 8mm documentary about Hitler Youth camps. He then moved to New York, where he worked on radio and landed a few Broadway roles, the best of which were directed by Elia Kazan. It was through Kazan’s influence that Widmark was auditioned by 20th Century Fox and put under contract, and immediately cast in Kiss of Death, for which he was nominated for an Oscar.

Critic James Agee described the character of Tommy Udo thus: “A rather frail fellow with maniacal eyes who uses a sinister kind of falsetto baby talk laced with tittering laughs. It is clear that murder is one of the kindest things he is capable of.” Certainly, Udo seems to delight in pushing an elderly wheelchair-bound woman down a flight of stairs. Of the spine-chilling snigger, Widmark explained that it derived from his nervousness at his first screen role, and “I’ve always had a goofy laugh.”

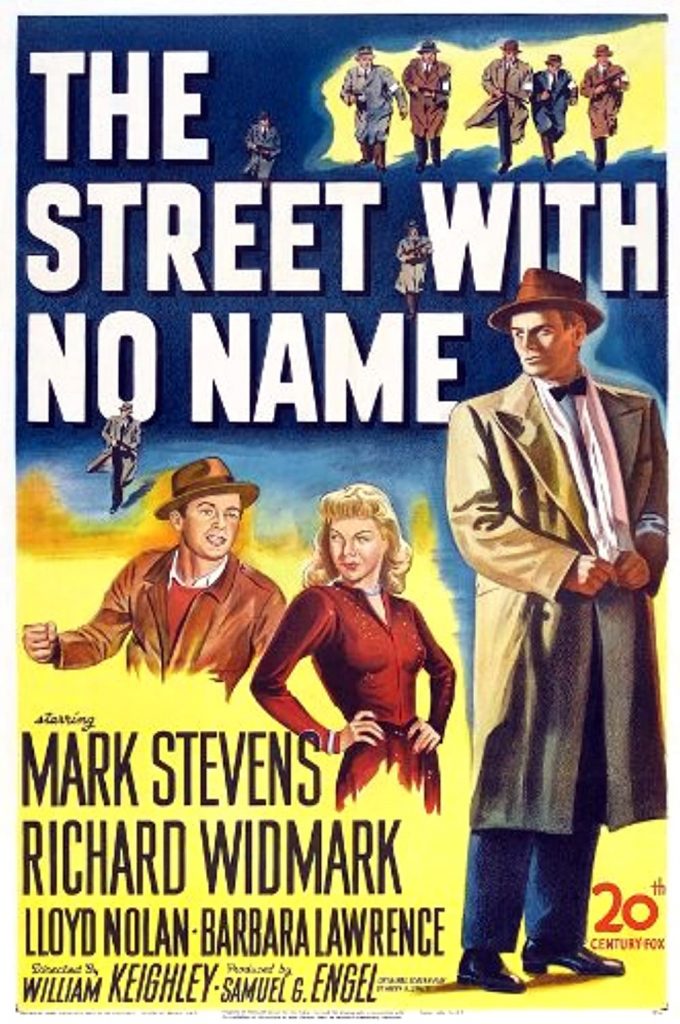

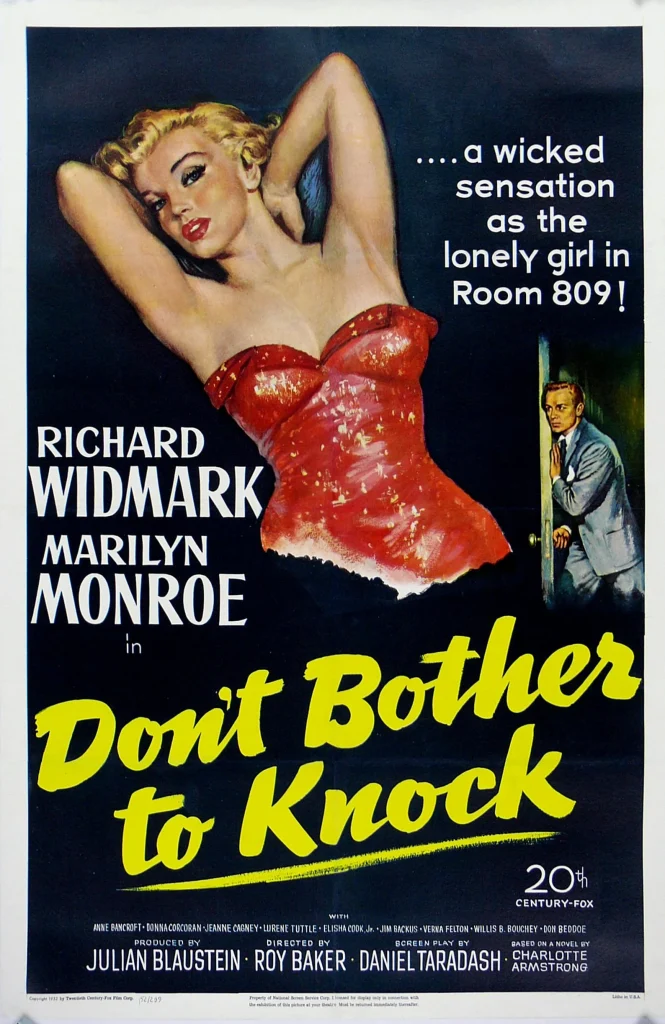

In the Hollywood tradition of stringent typecasting, Widmark reprised this sadistic character, with slight variations, in his next three movies, all released in 1948. In Street With No Name, he played a crooked fight promoter, wrapped up in a scarf and using inhalers, terrified of catching a cold, who wishes to run his gang “along scientific lines”. In one scene, later toned down to get past the censor, he beats up his wife (Barbara Lawrence), whom he suspects of having tipped off the police.

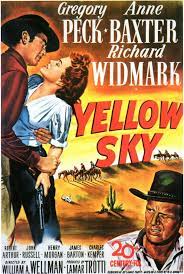

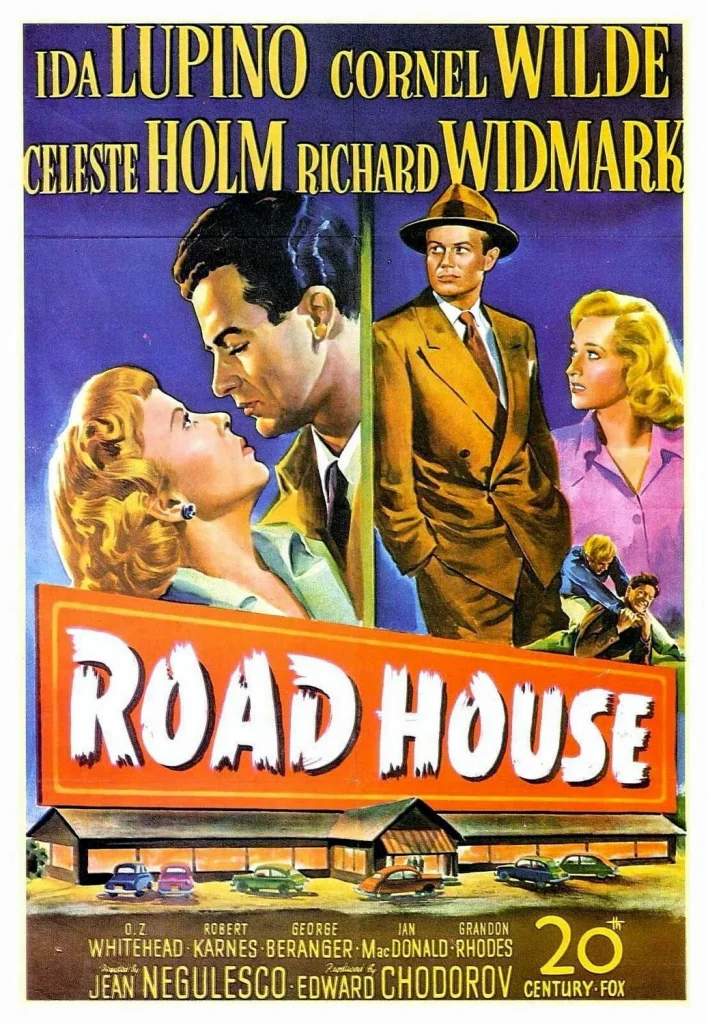

In Road House, he was a psychotic ex-serviceman pushed over the edge by sexual jealousy, and in the William Wellman western Yellow Sky he was the nastiest of the bank robbers opposing reformed outlaw Gregory Peck.

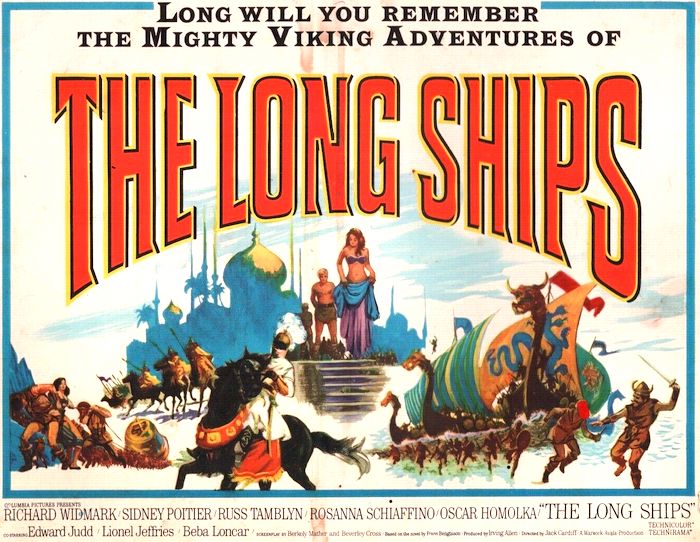

The last of his fanatical chortling villains was in Joseph Mankiewicz’s No Way Out (1950), in which he played a hospitalised racist hoodlum under the care of a black doctor (Sidney Poitier). So convincing was Widmark that a great deal of Poitier’s anger was genuine. In fact, the two actors became firm friends and appeared together again in two films, The Long Ships (1964) and The Bedford Incident (1965).

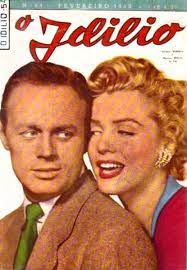

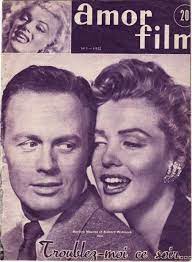

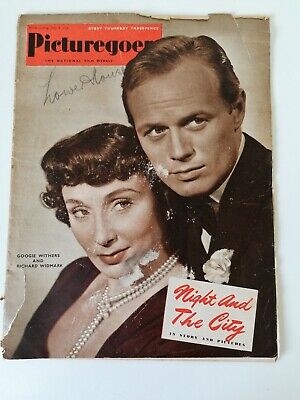

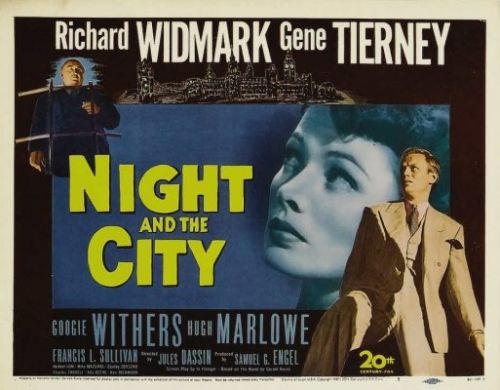

From the early 1950s, Widmark edged his way into more sympathetic roles, gradually entering the pantheon of Hollywood heroes. During the transitionary period, he gave one of his best performances in Jules Dassin’s Night and the City (1950), shot over 60 straight nights on location in London. As a small-time crook with ambitions to be a wrestling promoter, he is forced on the run by a racketeer before being killed and tossed into the Thames.

In the same year, Widmark crossed sides in Kazan’s Panic in the Streets, playing a doctor in the New Orleans public health service who hunts a gang of petty criminals carrying pneumonic plague. This time, he himself was upstaged by the villain (Jack Palance, in his screen debut).

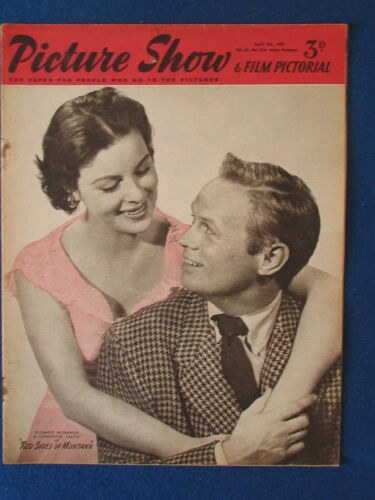

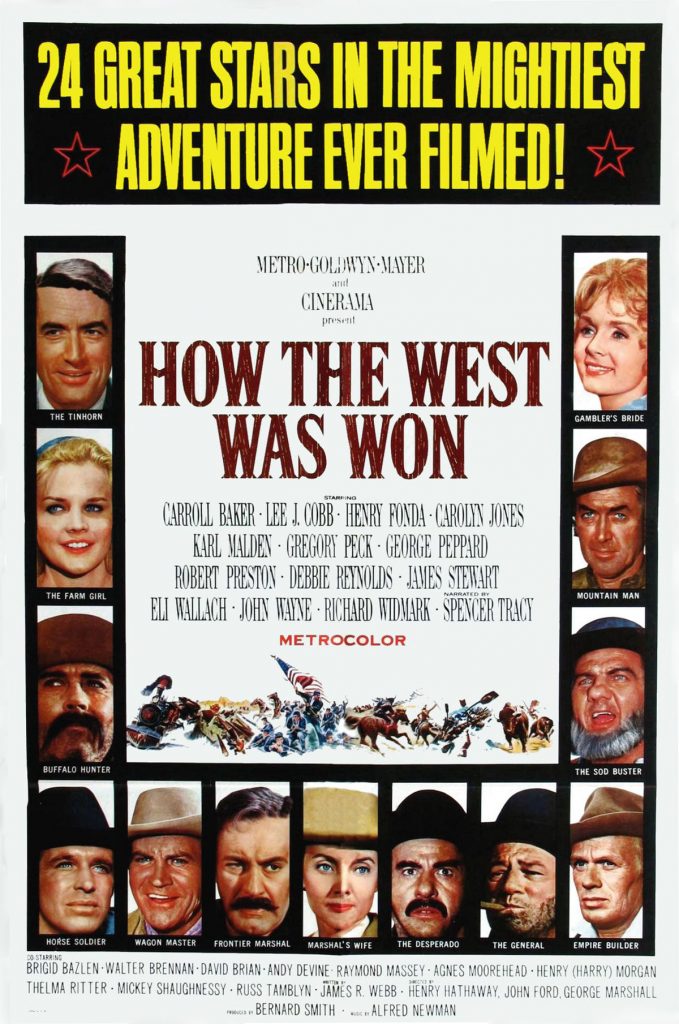

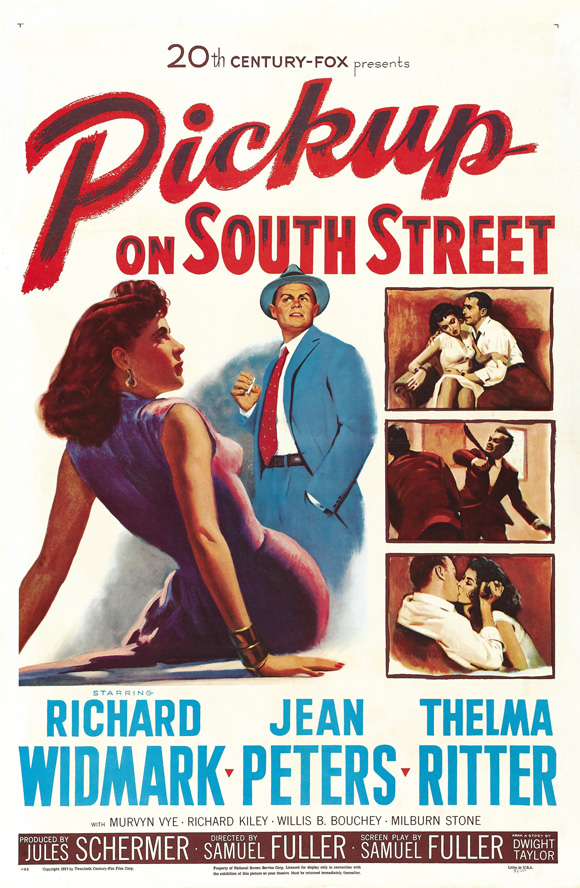

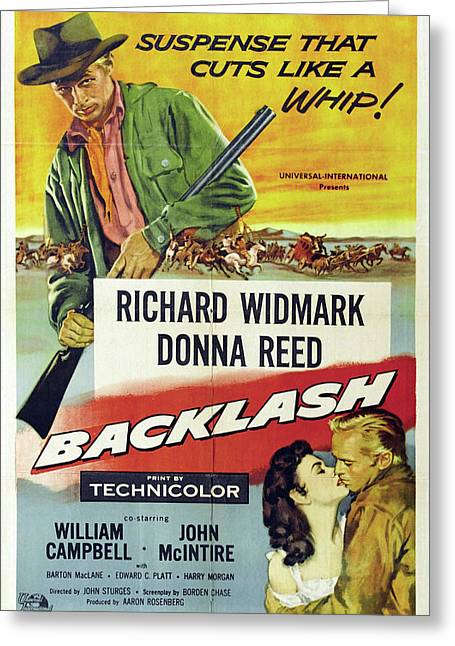

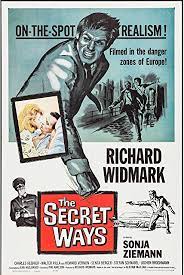

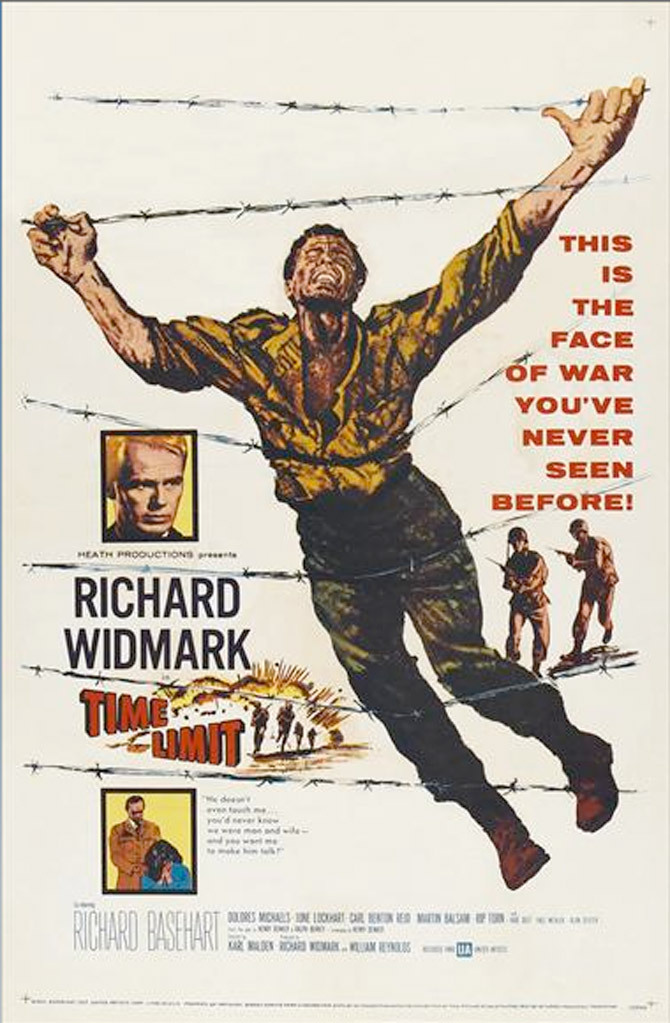

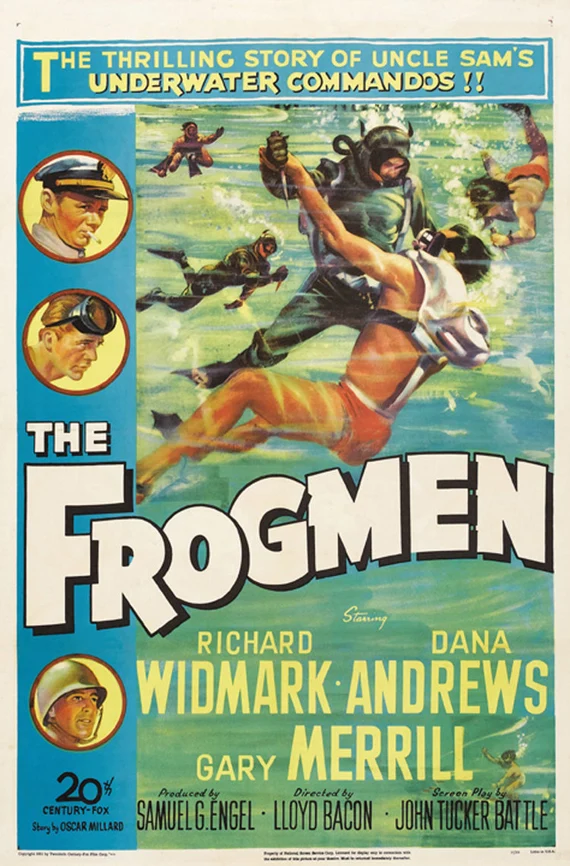

More good guys followed in war movies – Halls of Montezuma (1950), The Frogmen (1951) and Destination Gobi (1953) – and westerns Red Skies of Montana (1952), Broken Lance and Garden of Evil (both (1954) in which Widmark turned the steely-eyed, gaunt, albino-like figure of his psychopath characters into a straightforward, blue-eyed, muscular blond. But his white rat persona surfaced from time to time, giggle and all. In Sam Fuller’s Pickup on South Street (1953), he played a seedy pickpocket who inadvertently “lifts” some top secret microfilm, which he is prepared to sell to the “commies”. Widmark brilliantly presents the moral ambiguity of the man, finally turning against the spies out of revenge, not patriotism.

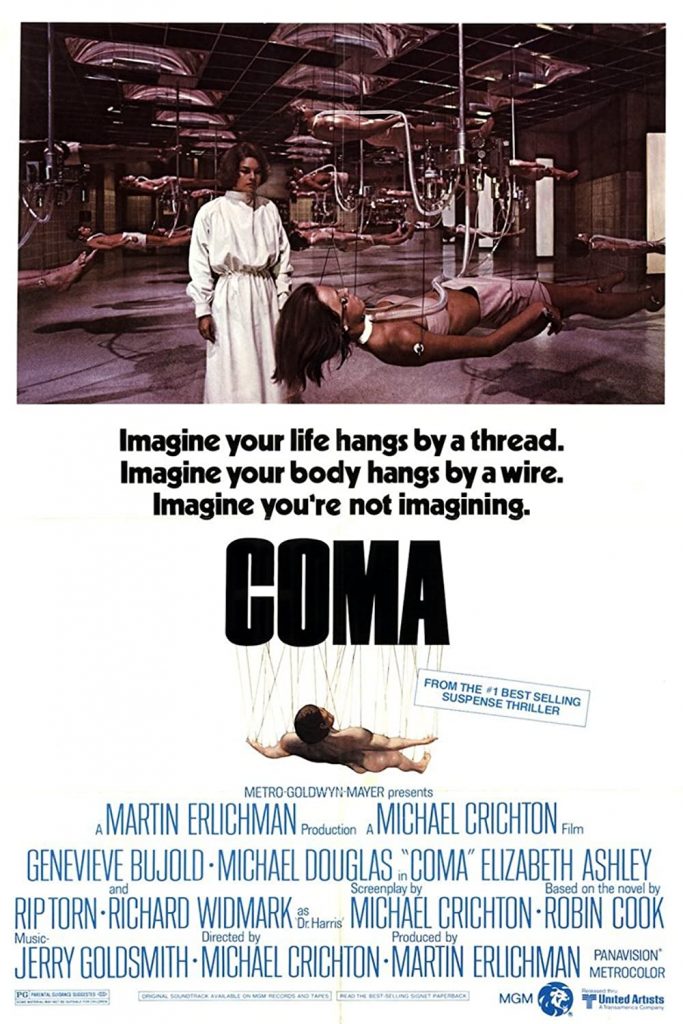

He was the heavy, challenging Robert Taylor in The Law and Jack Wade (1958), and Mr Ratchett, the millionaire victim in Murder on the Orient Express (1974), so detestable that almost every passenger on the train has a motive to kill him.

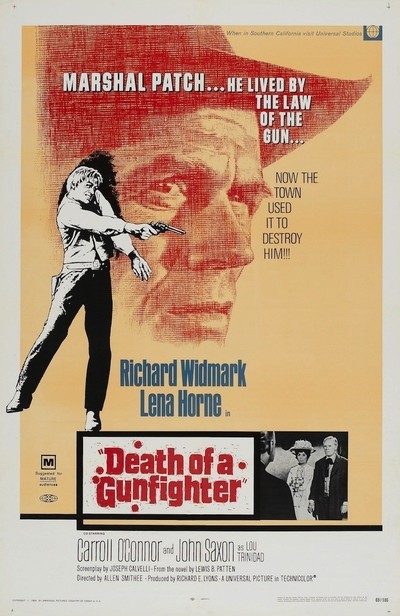

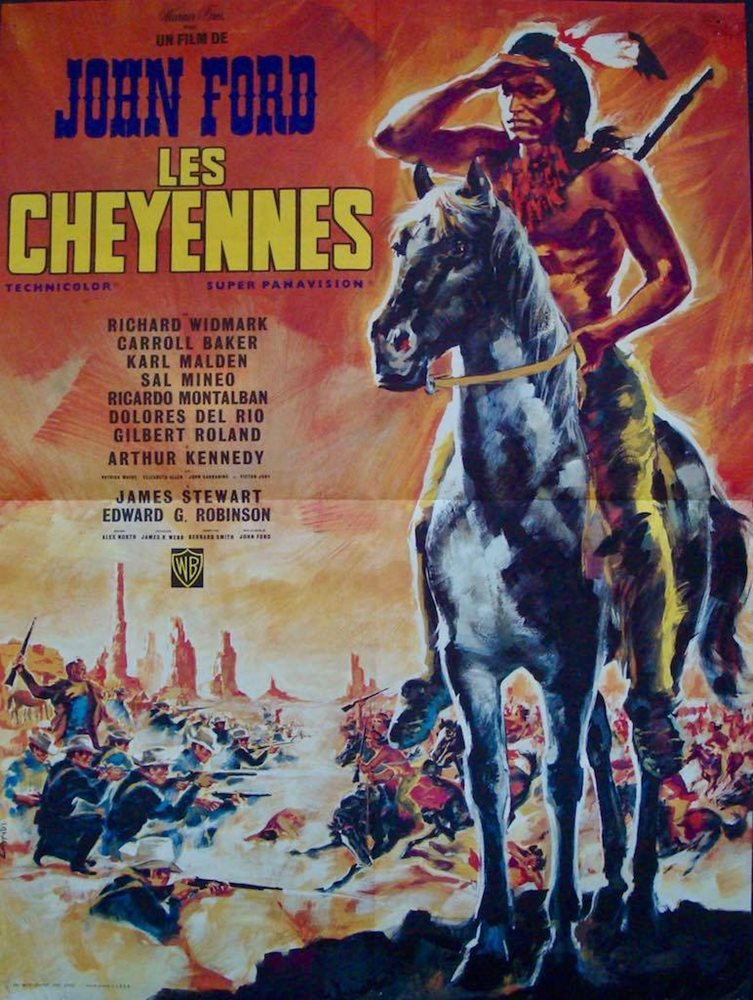

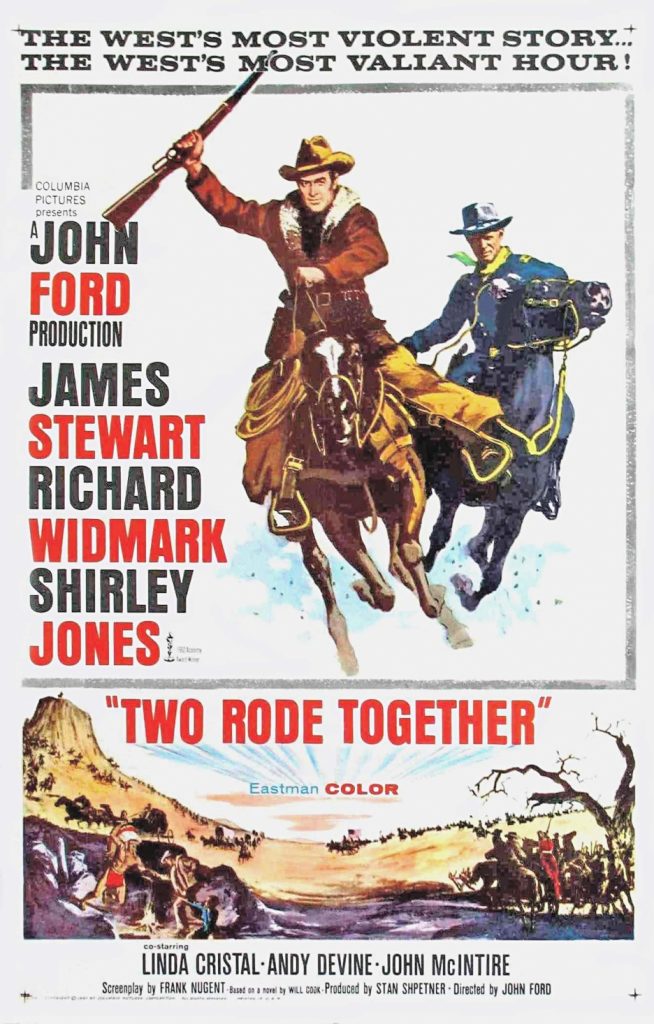

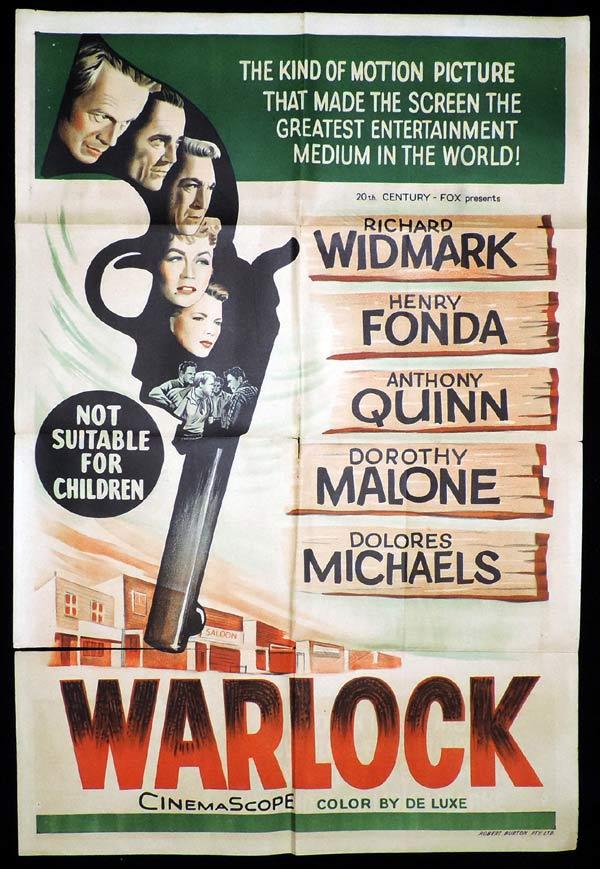

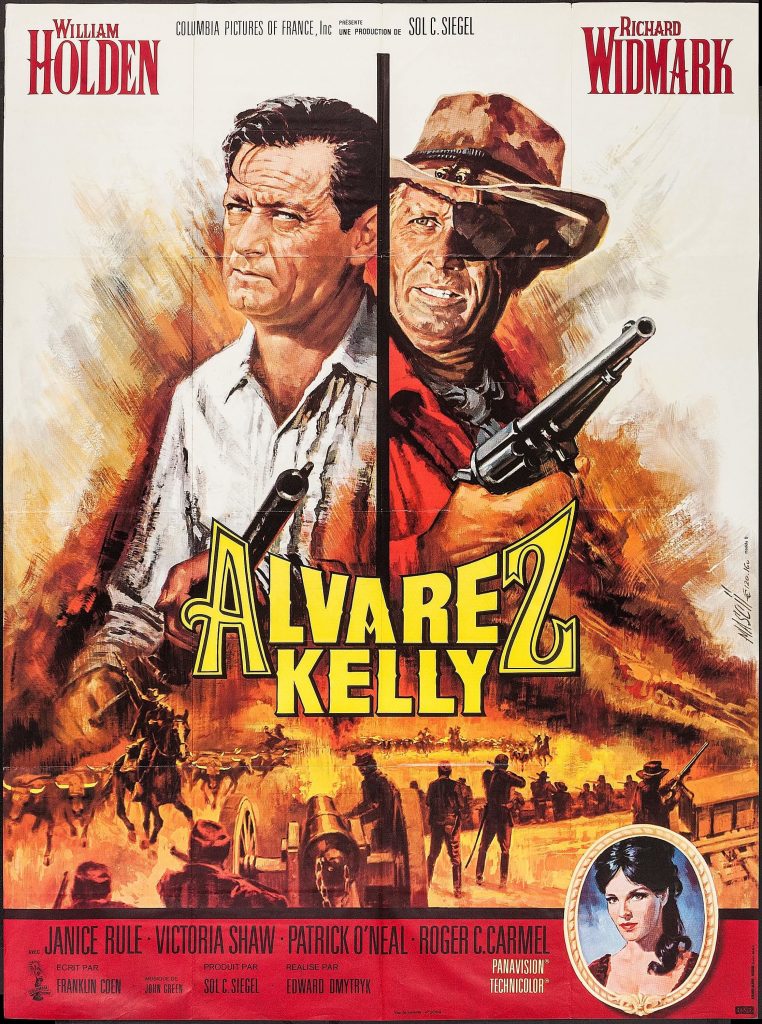

On the whole, however, Widmark played mainly hardbitten heroes, especially in a number of westerns, such as John Ford’s leisurely Two Rode Together (1961), in which he partnered James Stewart; Alvarez Kelly (1966), as William Holden’s antagonist; and The Way West (1967), billed third after Kirk Douglas and Robert Mitchum. “I love westerns,” Widmark commented. “I love the outdoors, I love horses. That’s why I raise them.”

Apart from his film work, he made a fortune investing in land and owned a couple of ranches for himself. He married former actor and screenwriter Jean Hazelwood in 1942, and claimed never to have even flirted with another woman. “After I was married I thought, ‘well, that’s it’. I never thought beyond that. I happen to like my wife a lot.”

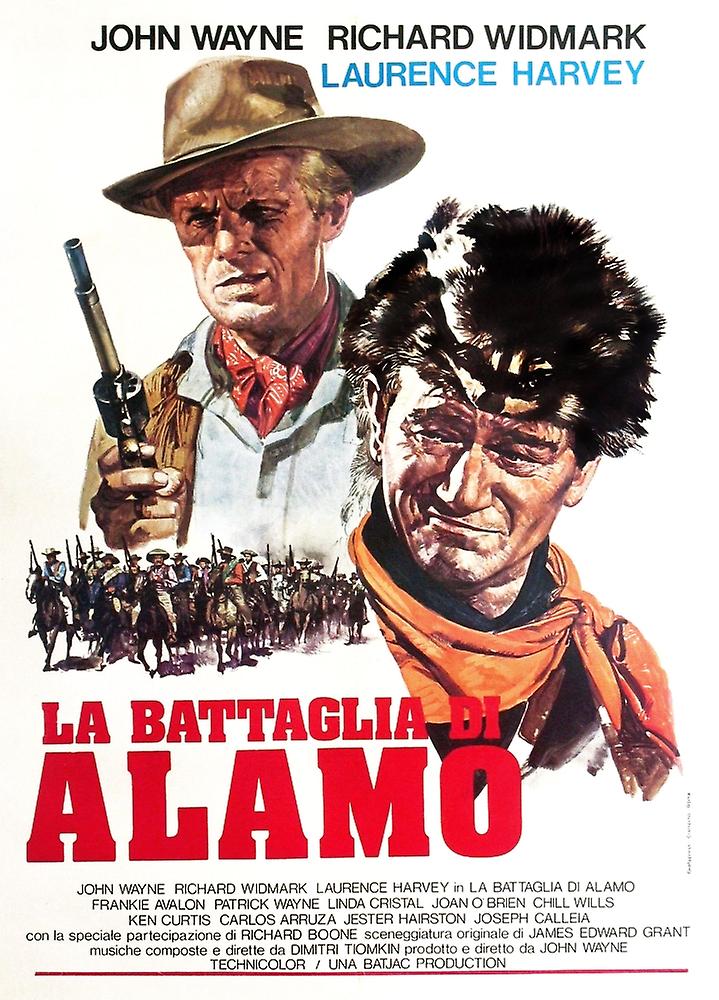

Politically, Widmark was a liberal, poles apart from John Wayne, who directed him in The Alamo (1960). Wayne wanted him to play Colonel William Travis, but Widmark insisted on playing Jim Bowie. “You’re not big enough,” Wayne told him. “I’ll be big enough,” Widmark replied. And he was.

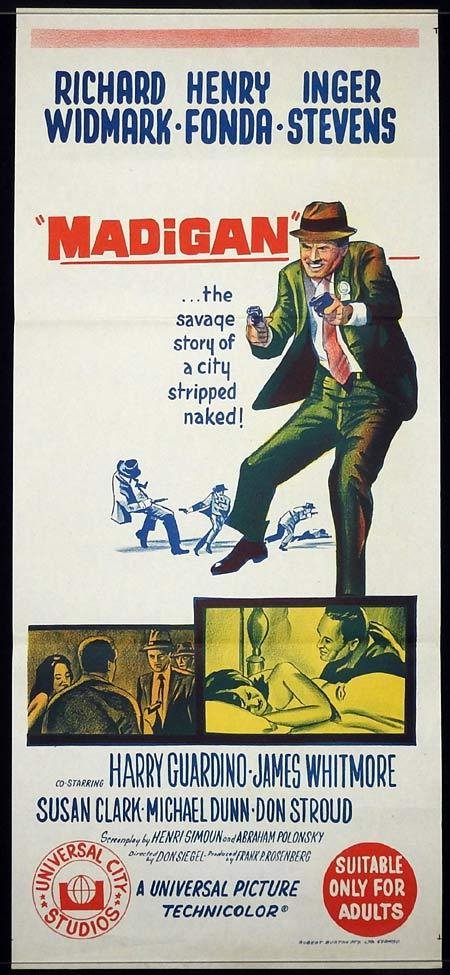

The following year, he was the belligerent prosecutor in Judgment at Nuremberg, curiously less sympathetic than Maximilian Schell’s defence attorney. In 1968, he took the title role in Don Siegel’s Madigan as a tough New York detective. Although he is killed at the climax, the character was resurrected for six TV movies in the early 1970s. Widmark played Sergeant Dan Madigan as a cold loner, speaking in metallic tones.

From the 1980s, his light hair turned silver, he made fewer appearances, but whenever he gave an interview, the character of Tommy Udo always came up, even though he had created that monster almost half a century earlier.

Jean died in 1997, but he is survived by his second wife, Susan Blanchard, whom he married in 1999, and his daughter Anne from his first marriage.

· Richard Widmark, actor, born December 26 1914; died March 24 2008

“The Guardian” obituary can also be accessed on-line here.