David Kosoff’s obituary in “The Guardian”:

The actor, writer and raconteur David Kossoff, who has died of cancer aged 85, could see the funny side of Jewishness, religion, even of God. He entertained a wide public without offence on this difficult tightrope because he could also see the funny side of himself. And one of his radio stories – he wrote dozens – ended with: “And Samson, giving the performance of his career, brought the house down.”

He made more than two dozen films, and, in 1956, gained a “British Oscar” from the then Society of Film and Television Arts for his performance in Wolf Mankowitz’s A Kid For Two Farthings, as the elderly confidant of a boy who believes his one-horned goat is a unicorn. He played a similar role in Mankowitz’s short film The Bespoke Overcoat (1956), that of Morry, which he had first given in 1953 at the Arts Theatre in London.

His other movies included I Am A Camera (1955), The Mouse That Roared (1959) and The Mouse On The Moon (1963). He was also credible and creditable in John Huston’s Freud (1962), where the waspish, Old Testament prophet side of his character came more into play than usual.

In the late 1950s, he was best known for playing the bucolic old rogue Alf Larkin in the television series The Larkins. It was often suggested to Kossoff that as an amiable countryside oaf, Alf was hardly the sort of part that gave full rein to his powers. He was sturdy in his defence. “Alf earns 10 times as much as Kossoff, mate,” he told one journalist. “He helps Kossoff to choose the parts he wants in straight plays and to say ‘No’ to the others. I like Alf … A lot of hard work went into creating him. He’s probably the best thing I’ve ever done.” He was even better pleased when Alf recorded cockney songs on several LPs.

But, crucially, Kossoff was famous – and much loved – in the 1960s for his simple and humorous paraphrasing of the Bible into his own stories, which he read on television and radio in the rich tones of an understated Jewish comedian. Nothing he did after it sustained his reputation at quite that level.

He had sprung to prominence in 1952 when he played the Russian Colonel Alexander Ikonenko in Peter Ustinov’s West End play The Love Of Four Colonels. He was well suited to underline the weakness of the colonel, one of four allied occupation colleagues, a man suddenly lost when scientifically inexplicable events do not fit in with his narrow materialism.

Kossoff was the son of a poor Russian East End garment worker. The poverty in which he grew up made him determined to better himself. He went to elementary school and the Northern Polytechnic, London. After leaving it in 1937, he spent a year as a draughtsman, took up furniture design, and then announced to his horrified parents that he wanted to be an actor.

Later, he asserted that he had sought out acting classes because that was the sort of place where you met attractive women. He also felt that the stage could offer more money. His parents, wanting him to have the security they lacked, were worried. Kossoff joked that they were the only parents of a child of call-up age relieved by the outbreak of the second world war.

But Kossoff began acting in 1943, and two years later joined the BBC radio repertory company. He combined his acting with illustrating and designing until his success in The Love Of Four Colonels.

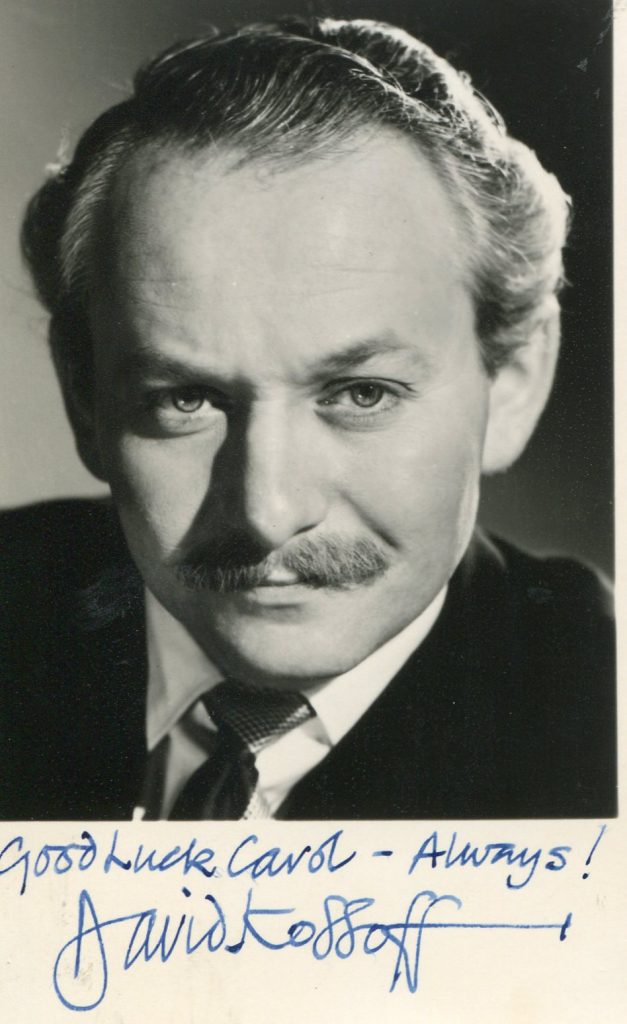

Small, bespectacled and prematurely white-haired, he was never part of the glitzier aspects of show business. He bought a dilapidated London house cheap, redesigned it himself and also used his own furniture designs.

But his forte was really the broadcast or the live one-man show, sometimes biblical, sometimes not. Once a restaurant even employed him to join diners at their tables for a while and then gradually slide into a partly extemporised cabaret, drawn from meeting the fellow diners, and including them as part of the performance. This idea did not have a long run, but was in its way groundbreaking. He said it wasn’t demeaning – he was simply providing a kick for people who wanted to meet someone they had seen on television.

Apart from the stage, cabaret, television, radio and records, his biblical tales also achieved book form. He wrote a string of books, mostly on related subjects and his way with biblical and other religious themes often underlined his own moral views. He believed that he had been “pushed” in the direction of writing because he had never encountered a rejection slip. His writing certainly had single-mindedness. Often he corrected page proofs of his books in his dressing room while fulfilling acting engagements. When appearing as Cinderella’s father, Baron Hardup, at the London Palladium, he missed his cue twice because he was working on his latest book. It did not prevent him correcting proofs of another book in his dressing room when he did a play with the singer Eartha Kitt in the West End – even on the first night.

Kossoff married Margaret Jenkins. They had two sons, of whom one, Paul, the guitarist with the rock group Free, died at 25 of a heart attack brought on by drug addiction. Kossoff had promised to devote a year to drug and other charity performances to celebrate his son’s withdrawal from drugs, taking no money himself. Instead, when the withdrawal from drugs proved to be a fatally forlorn failure, he fulfilled his promise as a tribute to his son’s memory.

He could laugh at himself when being more financially minded. He did several TV commercials, pointing out that Bible stories didn’t pay very well, but commercials did – and that, anyway, “it just occurred to me that God might have guided my hand to J Walter Thompson.”

His wife predeceased him. He is survived by a son and a daughter.

· David Kossoff, actor and writer, born November 24 1919; died March 23 2005