TCM Overview:

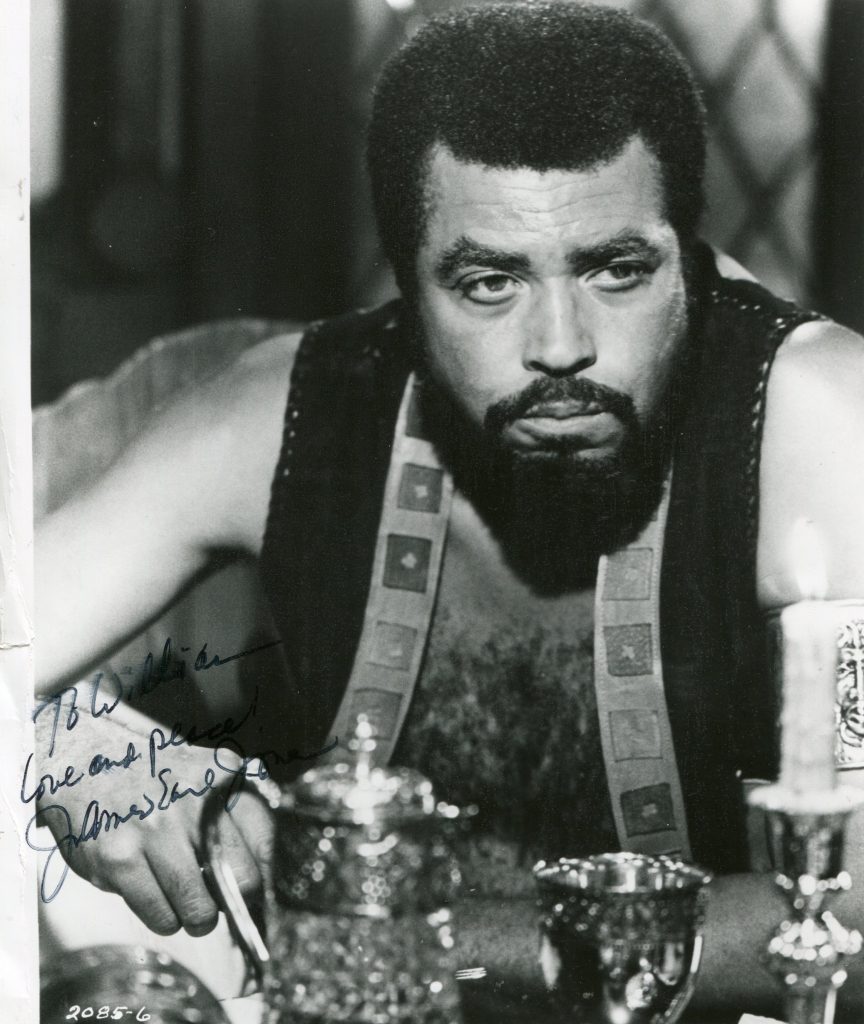

One of the preeminent stage and screen performers of his generation, award-winning actor James Earl Jones primarily functioned as a high-quality supporting player after a brief run in the 1970s as a leading man. But more famous than any onscreen role was his deep, resonant voice that first gave authority and menace to Darth Vader in “Star Wars” (1977), “The Empire Strikes Back” (1980) and “Return of the Jedi” (1983) – a startling achievement due to his overcoming a debilitating childhood stutter that remained with him throughout his career. Prior to his iconic voice performance in “Star Wars,” he made a name for himself on the stage, especially in Shakespearean roles not normally associated with being played by African-Americans. Once his voice became famous, it was only a matter of time until his face became renowned as well, which happened after appearing in a range of movies, from John Sayles’ small independent “Matewan” (1987) to “Field of Dreams” (1989) to a trio of blockbusters based on the novels of Tom Clancy, “The Hunt for Red October” (1990), “Patriot Games” (1992) and “Clear and Present Danger” (1994).

Born on Jan. 17, 1931 in Arkabutla, MS, Jones was raised by his mother, Ruth, a tailor and teacher, and his grandparents, John and Maggie, both farmers, after his father, Robert Earl, left the family before his birth. When he was five, the family uprooted itself to his grandparents’ farm in rural Jackson, MI – a move he later credited to causing his debilitating childhood stutter, in which he barely spoke to anyone but his family from ages 6-14. In fact, his stutter was so bad that he left his church because he was unable to read Sunday school recitations without the other kids laughing at him. When Jones reached high school in Brethren, MI, he overcame his stutter with the help of his English teacher, Donald Crouch. Crouch read a poem Jones had written, but challenged its authenticity by claiming he plagiarized it. Shocked by the accusation, Jones was further challenged to prove he wrote it by reciting the poem by heart in front of the class. Jones did, taking his first tentative steps toward overcoming his stutter, which remained with him throughout his career.

Meanwhile, in 1949, Jones earned a scholarship and enrolled at the University of Michigan, where he initially majored in pre-med. But Jones felt the lure of the stage and made his acting debut in a university production of “Deep Are the Roots” (1949). Soon he found himself enrolled in the drama program, while also eventually becoming a second lieutenant in the school’s Reserve Officer’s Training Program. After graduating in 1953, he spent two years in the Army Rangers, then left the service to pursue acting fulltime. He landed his first paying job as the understudy to Ivan Dixon in “Wedding in Japan” (1957), then debuted on Broadway as an understudy for the roll of Perry Hall in “The Egghead” (1957). Jones was back on Broadway the following year in “Sunrise at Campobello” (1958) and began his long affiliation with the New York Shakespeare Festival in 1959, with which he honed his craft in the title roles of “Othello,” “Macbeth” and King Lear.” He appeared off-Broadway in the seminal and acclaimed production of Jean Genet’s “The Blacks” (1961), then made his feature debut as the dedicated bombardier on Major King Kong’s B-52 in Stanley Kubrick’s classic satire, “Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” (1964).

Jones had his real breakthrough with a Tony-winning turn as first black heavyweight boxing champion Jack Johnson in “The Great White Hope” (1968), a role he reprised for the 1970 movie of the same name, which earned him an Oscar nomination for Best Actor. In 1969, Jones filmed several short segments for the fledgling kids’ show, “Sesame Street” (PBS, 1969- ), which were used to test whether or not children would be receptive to the show. The test audience responded most favorably to Jones slowly counting from 1-10. The segments were used when the show later aired. Meanwhile, he began taking leading features roles, including “The Man” (1972), in which he was the first black president; “Claudine” (1974), playing the garbage man-love interest of a ghetto mother (Diahann Carroll); “The River Niger” (1975) opposite Cicely Tyson; and “The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings” (1976), where he portrayed a fictional character based on Hall of Fame Negro League catcher, Josh Gibson.

Though working consistently on screen, his star burned brightest on the boards where – in addition to his celebrated work in Shakespeare plays – he inaugurated a long-standing collaboration with South African playwright Athol Fugard, acting in “The Blood Knot,” “Boseman and Lena” (1974) and “‘Master Harold’…and the Boys,” among others. He also portrayed Lennie in a 1974 Broadway revival of John Steinbeck’s “Of Mice and Men,” then performed the controversial one-man show “Paul Robeson” on Broadway (1977), which caused an uproar with Robeson’s son, who mounted a campaign to stop the production on the grounds that the story was “grossly distorted.” Nonetheless, Jones reprised the show in London the following year. That same year, Jones – or rather his voice – became unwittingly famous when “Star Wars” was released and became not only the highest-grossing movie at the time, but also a cultural phenomenon that would stretch far into subsequent generations. Though director George Lucas hired actor David Prowse to play Dark Vader on screen due to his towering 6’8″ height, he wanted a different, more imposing voice. So he found Jones and paid him $9,000 for less than three hours of work. But because he was only a voice actor, Jones did not receive points on the gross – a luxury given to the other actors by Lucas. When “Star Wars” made tons of money, Jones missed a big payday. Lucas did, however, make up for most of it with a generous Christmas bonus.

Back to appearing on screen, Jones was Balthazar in “Jesus of Nazareth” (NBC, 1977), then starred opposite Robert Duvall as Malcolm X in “The Greatest” (1977), starring Muhammad Ali as himself in this biopic about how he overcame obstacles to become the greatest boxer of all time. Jones then had great success on television in the groundbreaking roles of Dr. Jerry Turner on “As the World Turns” (CBS, 1956- ) and Dr. Jim Frazier on “The Guiding Light” (CBS, 1951-2007), becoming one of the first African-American regulars featured on the networks’ daytime dramas. He ventured into primetime series as the titular star of “Paris” (CBS, 1979-1980), playing the erudite police captain of a special detective unit of the Los Angeles Police Department, then portrayed author Alex Haley in the acclaimed miniseries sequel “Roots: The Next Generation” (ABC, 1979). After starring in two miniseries – “The Golden Moment: An Olympic Love Story” (NBC, 1980) and “Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones” (CBS, 1980) – Jones once again provided the rich, menacing voice to Darth Vader in “The Empire Strikes Back” (1980), including immortalizing the famous line, “Luke, I am your father.”

That same year, Jones made a return to the stage, appearing in Athol Fugard’s “A Lesson From Aloes” (1980) before delivering an acclaimed performance as “Othello” (1982) on Broadway in a production where he starred opposite future wife Cecilia Hart. Following a third turn as Darth Vader for “Return of the Jedi” (1983), he appeared in two forgettable features, “City Limits” (1985) and “Soul Man” (1986), before playing a former Negro League baseball player-turned-bitter garbage man in August Wilson’s “Fences” (1987), for which Jones earned his second Tony Award for Best Leading Actor in a Play. Also that year, he appeared in “Matewan” (1987), John Sayles’ compelling drama depicting a violent labor dispute in 1920s rural West Virginia. Following a co-starring turn in the antiwar drama “Gardens of Stone” (1987), Jones was the picture of patriarchal kingship in “Coming to America” (1988), playing the regal father of Prince Akeem (Eddie Murphy), the heir to the thrown of the fictional African country of Zamunda, who refuses to enter into an arranged marriage and instead sets off to find his true love in America. He next delivered a fine performance both comic and moving in “Field of Dreams” (1989), playing a reclusive author kidnapped by an Iowa farmer (Kevin Costner) who is building a baseball field instead of planting corn.

After playing a CIA official in “The Hunt for Red October” (1990), Jones turned to the small screen, where he delivered an Emmy-winning performance as Junius Johnson in “Heat Wave” (TNT, 1990), a compelling drama about the 1965 Watts riots. He earned a second Emmy Award that year playing a disgraced cop-turned-private investigator in “Gabriel’s Fire” (ABC, 1990-92). Though a hit with critics, the series failed to generate an audience and was soon cancelled. Jones next starred opposite Robert Duvall in the period western, “Convicts” (1991), written by Horton Foote, then played Police Inspector Nkuru in “The Ivory Hunters” (TNT, 1992). Following his portrayal of the judge in “Sommersby” (1993), two rare starring turns came his way; first as the South African preacher searching for his son in the remake of “Cry, the Beloved Country” (1995), and then as Robert Duvall’s half-brother in “A Family Thing” (1996). Though he brought his usual majesty to both roles, in each case, his acting was grander than the material itself, but at least his fans were able to savor his extended minutes before the camera. Prior to both films, Jones’ distinct baritone was put to excellent use in “The Lion King” (1994), when he voiced the powerful Mufasa, king of the pride and father of the cub, Simba.

Around the time of “The Lion King,” Jones made another stab at series television with the family drama “Under One Roof” (CBS, 1995), but once again, he saw a worthwhile project cut short. After playing Hume Cronyn’s best friend in “Horton Foote’s Alone” (Showtime, 1997), Jones voiced Mufasa for the direct-to-video sequel, “The Lion King II: Simba’s Pride” (1998), then hosted segments on the Kennedys and Somalia for “CNN Perspectives” (CNN, 1998), for whom he also intoned the words “This is CNN” for their cable network ID. Jones also starred as a retired physician whose friendship with a young white boy sparks a racial conflict in a small town in the Showtime movie “Summer’s End” (1999), a role that earned him a Daytime Emmy Award for Outstanding Performer in a Children’s Special. Meanwhile, he enjoyed a series of recurring roles on several series, including “Homicide: Life on the Street” (NBC, 1993-99). Meanwhile, throughout his career, Jones put his voice to good use in numerous commercials, including spots for Chrysler, Goodyear, Reuben’s dinners, coverage for the 2000 and 2004 Summer Olympics, and The Bell Atlantic Yellow Pages.

As his career entered its fifth decade, Jones found himself performing less in films and more on the small screen, including an appearance in the miniseries “Feast of All Saints” (CBS, 2001), based on the Anne Rice bestseller, and a guest-starring role on “Everwood” (The WB, 2002-06), for which he earned an Emmy Award nomination. In 2005, he enjoyed tremendous reviews for his high-profile turn playing crotchety Norman Thayer opposite Leslie Uggams in an all African-American interpretation of Ernest Thompson’s play “On Golden Pond” at Broadway’s Court Theater. For the third time in his career, Jones was nominated for a Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play, though a bout with pneumonia forced him to quit the show, which caused the show itself to close prematurely. That same year, Jones revisited his most iconic role, once again voicing Darth Vader for George Lucas’ final prequel film “Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith” (2005). A few years later, he joined Debbie Allen’s all-African-American production of Tennessee Williams’ classic “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof” (2008), which was produced on Broadway at the Broadhurst Theatre. In 2009, Jones received a Life Achievement Award from the Screen Actors Guild.

The above TCM overview can also be accessed online here.

Telegraph obituary in 2024.

James Earl Jones, who has died aged 93, was hailed in the 1960s as the most exciting presence in the American theatre since Marlon Brandoand became the pre-eminent black stage actor of his generation, but achieved his widest fame as the voice of Darth Vader in Star Wars.

Jones specialised in endowing his stage roles with an ineffable, if often sorely tested, nobility. But he had no interest in being a standard-bearer for the dignity of black people, as Sidney Poitier was in the cinema.

Where Poitier would not play Othello on the grounds that the Moor could be seen as a white man’s dupe, Jones could not resist the character’s complexities and played the part seven times. Theatrical lore had it that he was a serial romancer of his Desdemonas, but he insisted that he had only been involved with two of them – both of whom he married.

His breakthrough role came in 1967 in The Great White Hope (Arena Stage, Washington DC), Howard Sackler’s play based on the life of the boxer Jack Johnson. Those who knew the diffident, introspective Jones wondered if this flamboyant part would be beyond his range, but he triumphed, winning a Tony Award after the play transferred to Broadway.

If anyone deserves to become that occasional thing, a star overnight, then Mr Jones deserves no less,” declared Clive Barnes in The New York Times, although after 14 years as a struggling actor, the 37-year-old Jones queried the “overnight”. He recreated the role for Martin Ritt’s film of 1970, but as with many of his films he disliked the result, although he was nominated for an Oscar.

He discussed his stage work in forensic detail in his autobiography Voices and Silences (1993) but devoted no more than two paragraphs to Star Wars; he seemed to be not so much resentful of the space epic’s dominance in his professional life as wilfully oblivious. He would never, as his co-star Sir Alec Guinness did, have told autograph-hunting children that they should stop watching Star Wars, but if they asked him to repeat his lines from the films he would admit that he had no recollection of them.

Darth Vader’s spacesuit, breathing mask and samurai helmet were inhabited by the English bodybuilder David Prowse, who was originally supposed to supply his voice as well. But the director George Lucas felt that Prowse’s marked West Country accent – the rest of the cast dubbed him “Darth Farmer” – did not quite suit the galaxy’s most evil villain.

Lucas decided Vader’s lines should be dubbed by a commanding bass. Jones’s basso profundo voice – “Deep, rumbling, august: it’s the sound Moses might have heard when addressed by God,” according to one critic – was perfect, less familiar than that of Orson Welles, who was also considered, but just as distinctive. His vocals were filtered through the sound of a scuba diver’s breathing regulator.

Jones was paid only $7,000 for his work on the first Star Wars film (1977), although Lucas doubled the fee when it looked like it might be a hit. He reprised the role in the sequels The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983) and again when the Star Wars gravy train clanked back into life in the new millennium, in Revenge of the Sith (2005) and Rogue One (2016). He also voiced King Mufasa in the 1994 Disney animation The Lion King (a role turned down by Sean Connery), and again in the remake of 2019.

That his voice, which was in constant demand for documentaries and commercials, should have become his fortune was an irony on which Jones often reflected, as the stresses and privations of his childhood had left him with a pronounced stutter; indeed, for much of his boyhood he was functionally mute.

James Earl Jones was born at his maternal grandparents’ tenant farm in Arkabutla, Mississippi, on January 17 1931, in a four-bedroom farmhouse that already housed 11 other family members. His mother Ruth, née Connolly, had separated from her husband, Robert Earl Jones, before James was born; her family did not approve of Robert, a boxer and troubadour actor, and James would not meet his father until he was 21

When he was small his mother left to live as a migrant worker in the Delta, and he was brought up by his grandparents, who between them had Irish, Cherokee and Choctaw as well as African ancestry. He took pride in his mixed heritage, something that later made him suspicious of the politics of racial identity – as did the excessive hatred of white people constantly expressed by his grandmother, “the most racist person I have ever known”.

The family moved to a new farm in Michigan when James was five, an upheaval that exacerbated his sense of displacement, and he began to stutter, an affliction so humiliating that within a year he had virtually stopped speaking altogether.

He was simply regarded as an oddity by his family and teachers until, at 14, he wrote a poem that impressed one master, who encouraged him to read it out loud; James was surprised to discover himself the possessor of a strong, deep voice. He developed his confidence by reading Shakespeare and Poe out loud in the classroom, and went on to be a star of school plays and debates.

In the meantime James’s father Robert had become a well-known film actor, and when he saw a picture of him in a magazine, he announced his intention to become an actor, which earned him a clout from his grandfather.

Instead James went to study Medicine at the University of Michigan. But he intended to join the Army and firmly believed that he was destined to meet his end in Korea, so he switched to drama and in the end did not bother to take his degree.

In the event he got no further than Colorado before he was discharged, his commanding officer advising him that although he had the makings of a fine soldier he should not leave his ambition to be a professional actor untried.

He moved to New York and stayed for a time with his father; they bonded over discussions of theatrical technique, and would eventually act together several times.

The GI Bill funded his studies at the American Theater Wing, and he also scraped together money to attend private classes run by Lee Strasberg. He was too shy to strike up a conversation with his classmate Marilyn Monroe.

He scratched a living for many years. In December 1963 Newsweek noted that he had acted in 18 plays in the previous 30 months and still earned “less money than the average off-Broadway stagehand.” But his success in The Great White Hope brought him some security.

His stature as an actor grew with a fine King Lear in 1973 off Broadway, and an outstanding performance as the kind-hearted accidental killer Lennie in Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men (Brooks Atkinson, 1974-75).

A 1978 tour of a one-man play about his hero, the actor and civil rights activist Paul Robeson, saw him at odds with leading black activists over his insistence on a warts-and-all portrayal; he was dogged by protesters so vehement that the police gave him an armed bodyguard.

Jones became an increasingly intractable perfectionist. During a long run as Othello opposite Christopher Plummer’s Iago (1981-82), he insisted on the dismissal of his director, Peter Coe.

His role as an ex-baseball star reduced to working as a garbage collector in August Wilson’s Fences (1987-88) won him another Tony and was seen as the crowning glory of his stage career, but the run was beset by arguments between star and playwright (Jones rewrote the ending). Thereafter he did no major stage work for nearly 20 years.

Jones made his film debut as Lt Lothar Zogg in Kubrick’s Dr Strangelove (1964). He cared neither for Kubrick nor the film’s “puerile” humour.

He favoured “simple films that tell a simple story” and his favourite roles included America’s first black president in The Man (1972); a garbage man romancing Diahann Carroll in Claudine (1974); a striking coal miner in Matewan (1987); a reclusive novelist based on JD Salinger in Field of Dreams (1989); and Stephen Kumalo in Cry, the Beloved Country (1995). In the 1990s he played the CIA boss Admiral Greer in the Tom Clancy adaptations The Hunt for Red October, Patriot Games and Clear and Present Danger.

On television he was the first African-American to have a regular role in a soap opera, playing Dr Jerry Turner in As the World Turns in the mid-1960s; whenever he was unavailable Brock Peters would deputise for him, as it was thought the audience would see them as interchangeable. He had fond memories of a 1968 episode of Tarzan in which he played a tribal chief and sang with the Supremes, playing nuns.

He was Alex Haley in Roots: The Next Generations and King Balthazar in Jesus of Nazareth. He turned down the lead roles in Quincy and The Streets of San Francisco to concentrate on his stage work, and although he did later star in his own detective series, Paris (1979), it flopped. He had better luck in the 1990s as a private eye in Gabriel’s Fire, for which he won an Emmy.

An Indian summer in the theatre began with the Henry Fonda role in On Golden Pond (Cort Theatre, 2005) and a titanic performance as Big Daddy in Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof on Broadway and in London (2008-10). His role as the chauffeur opposite Vanessa Redgrave in Driving Miss Daisy (2010-11), again in New York and London, generated real theatrical magic; later he toured Australia in the play alongside Angela Lansbury.

His attempt to recapture his chemistry with Vanessa Redgrave as a superannuated Benedick and Beatrice in Mark Rylance’s production of Much Ado About Nothing (Old Vic, 2013) was a gamble that failed. In 2015 he appeared with Cicely Tyson in The Gin Game on Broadway.

Jones benefited a good deal from the therapy he practised with the “primal scream” pioneer Arthur Janov. The farmhouse he built in rural New York was an indispensable refuge.

He maintained relations with his remaining family in Mississippi, some of whom, he revealed, never quite came to terms with his appearances on film and television. “‘That ain’t you, is it?’ they say hopefully. ‘You ain’t no actor, is you?’”

James Earl Jones was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1992 and an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement in 2011.

He married first, in 1968 (dissolved 1972), Julienne Marie and secondly, in 1982, Cecilia Hart. She died in 2016; they had a son, Flynn.

James Earl Jones, born January 17 1931, died September 9 2024.