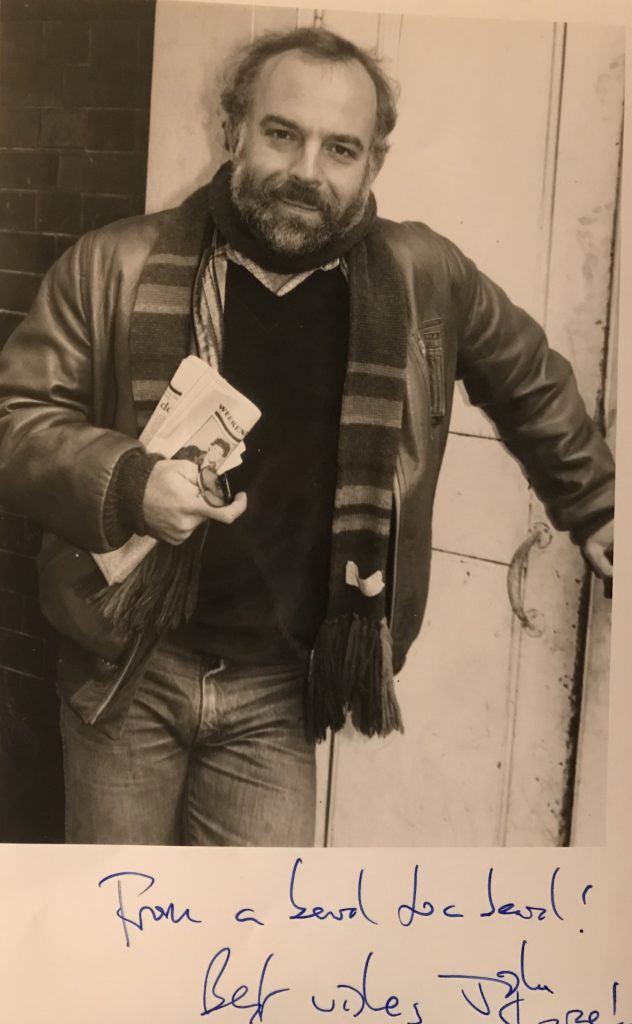

John Shrapnel. Obituary in “The Guardian” in 2020

Richly variegated and utterly plausible, with a distinctively weak “r”, the voice of the actor John Shrapnel, who has died aged 77 after suffering from cancer, was instantly recognisable on stage or screen over the past 50 years. He was therefore much in demand for voiceover work on documentaries or television adverts. He always sounded warm and urgent.

But his glory was on the stage, often with the Royal Shakespeare Company or the National Theatre, for whom he played leading and prominent supporting roles from 1968 onwards, including a clutch with Laurence Olivier’s NT company at the Old Vic – Banquo in Macbeth, Pentheus in the Bacchae and Orsino in Twelfth Night – between 1972 and 1975.

His NT debut came as Charles Surface in Jonathan Miller’s remarkable, grimily realistic 1972 production of The School for Scandal. He worked well and often with Miller: as a notable, sweating Andrey in Chekhov’s Three Sisters at the Cambridge theatre in 1976; and in Miller’s BBC television Shakespeare series of the 1980s, when he played Alcibiades opposite Jonathan Pryce’s Timon of Athens, Hector in Troilus and Cressida and Kent to Sir Michael Hordern’s gloriously distracted King Lear, saddled with the equally senescent Fool of Frank Middlemass.

Shrapnel was always interesting in these “solid” roles because he played them with such force and intelligence. He oozed gravitas and could make dullness seem virtuous, as he did with Tesman in a 1977 Hedda Gabler with Janet Suzman at the Duke of York’s theatre in 1977, or, late on, as a tremendous Duncan in the Kenneth Branagh Macbeth for the 2013 Manchester international festival.

Unusually, he was marvellous as both Brutus (Riverside Studios, 1980) and Julius Caesar (for Deborah Warner, at the Barbican, 2005) in the same play. And he made a final indelible impression as an archbishop in the 2017 televised version of Mike Bartlett’s King Charles III, starring his friend Tim Pigott-Smith in his last TV appearance, too.

Shrapnel was born in Birmingham, the elder son of the Guardian’s parliamentary correspondent Norman Shrapnel and his wife Myfanwy (nee Edwards). One of his ancestors, Lt Gen Henry Shrapnel, invented the exploding cannonball and gave his name to the

Manchester, and, when the family moved south, the City of London school, where he played Hamlet.

He took a degree at St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, and made a professional debut as Claudio in Much Ado Nothing at the new Nottingham Playhouse in 1965.

His major film debut was in Franklin J Schaffner’s Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) starring Suzman and Michael Jayston, and he scored a string of big successes on television as the Earl of Sussex in Elizabeth R (1971) with Glenda Jackson – he would be Lord Howard to Cate Blanchett’s Gloriana in Shekhar Kapur’s Elizabeth: The Golden Age in 2007 – as Sir Percival Glyde in The Woman in White (1982) with Diana Quick and Ian Richardson, and as Semper in Tony Palmer’s Wagner (1983) alongside Richard Burton in the title role and the great German actor Ekkehard Schall as Franz Liszt.

An intensity of presence on the stage, as well as a forbidding authority, made him a natural Claudius in Hamlet, but he added something else in Miller’s production of that play (with Anton Lesser) at the Donmar in 1982: a moving and almost sympathetic study of a man seriously under-endowed with imagination.

This ability to convey psychological layers in powerful figures served Shrapnel well both in John Barton’s 10-play epic, The Greeks, at the Aldwych in 1980, when he doubled a laconically wry Agamemnon with an imperious Apollo; and, especially, as the monstrously unflinching King Creon in Sophocles’ Oedipal Theban trilogy, a role he played twice – first, in Don Taylor’s BBC television adaptation in 1986 (Juliet Stevenson as Antigone, John Gielgud as Tiresias), and then for the RSC in Timberlake Wertenbaker’s version directed by Adrian Noble in 1992.

In the second of these his purple-suited tyrant, with a face of granite and a voice of liquid gravel, became strangely battered and susceptible to emotional pleading. Creon does not cave in, and nor did Shrapnel, but he always found colour and humanity in his inhumanity.

He played a jovial Samuel Pepys in Palmer’s television film England, My England (1995), written by Charles Wood and John Osborne, and starring an unlikely duo of Michael Ball as Henry Purcell and Simon Callow as King Charles II; a non-speaking, dog-hunting taxidermist in the 101 Dalmatians film (1996) starring Glenn Close as Cruella De Vil; Julia Roberts’s British press agent in Roger Michell’s Notting Hill (1999); and another Greek worthy, old Nestor, in Wolfgang Petersen’s all-action, highly enjoyable Troy (2004) starring Brad Pitt as Achilles.

He was a Russian admiral in K-19: The Widowmaker (2001), Kathryn Bigelow’s gripping movie, with Harrison Ford, about the Russian nuclear submarine malfunction.

One of Shrapnel’s sons, Lex, also appeared in that film, but their blood relationship was more fruitfully and indeed movingly mined in a 2015 Young Vic revival of Caryl Churchill’s A Number, a poignant, poetic piece about cloning and parenting in which John played Salter, the crazy scientist meddling with genetic material, and Lex his son Bernard.

Later in the same year Shrapnel rejoined Branagh in his season at the Garrick, playing a powerful Camillo in The Winter’s Tale and a mutinous old actor laddie in Terence Rattigan’s Harlequinade. He was the sort of actor any manager or producer wanted in his company; first name on the team sheet.

Outside his work, Shrapnel loved mountaineering, skiing and music.

He is survived by his wife, Francesca Bartley, a landscape designer (and a daughter of Deborah Kerr), whom he married in 1975, by their three sons, Joe, Lex and Thomas – and by his younger brother, Hugh.