Nina Foch obituary in “The Independent” in 2008.

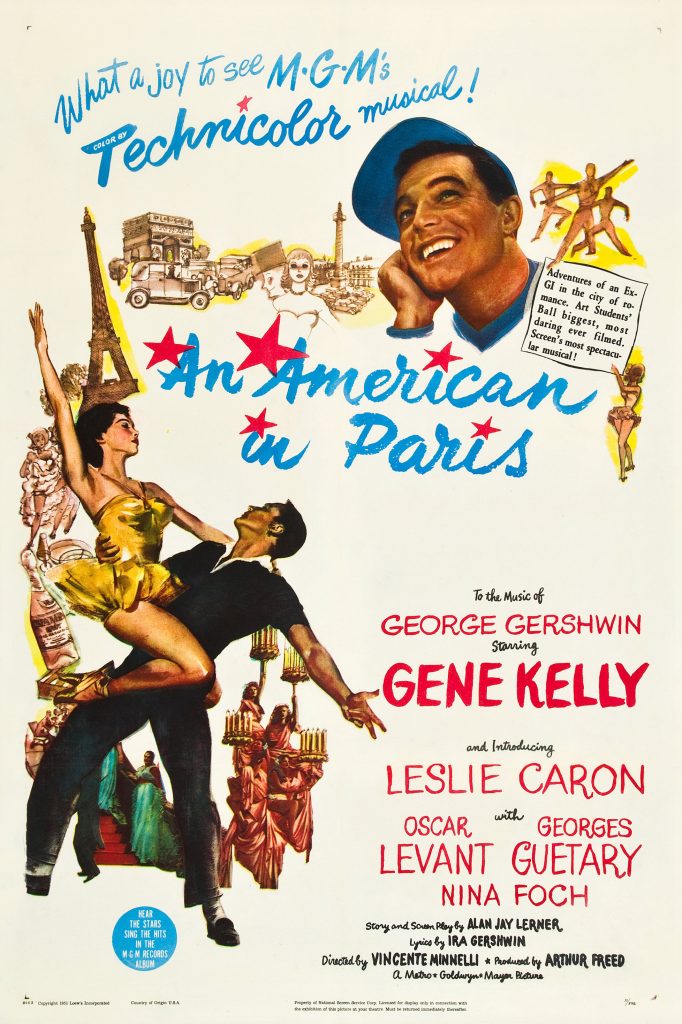

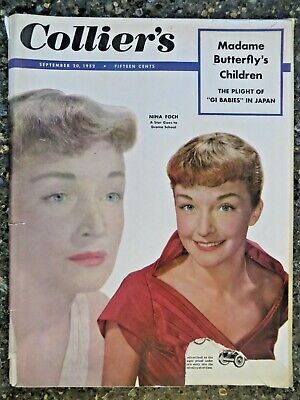

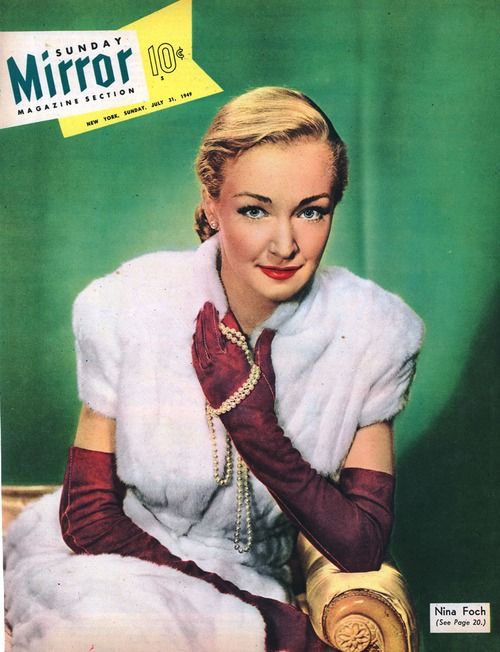

Nina Foch who has died aged 84, is not the first member of the cast of An American in Paris (1951) that comes to mind, but she brought a much needed acerbity, wit and psychological depth to the complacent world of this Vincente Minnelli musical. In fact, Foch’s personality was so strong that a monologue about her failure with the opposite sex was cut so as not to unbalance the cheery tone of the film. Foch did have a tendency to steal scenes in most of the films she was in, her roles alternating between prey and predator, sometimes being both at once.

In An American in Paris, the tall, cool and sophisticated Foch was perfectly cast as Milo Roberts (“as in Venus de”), a rich expatriate widow and patron of the arts, whose interest in artist Gene Kelly is amorous as well as professional. “Nice dress,” he says. “What’s holding it up?” “Modesty,” she replies. But her smile and quips hide the fury of a scorned woman.

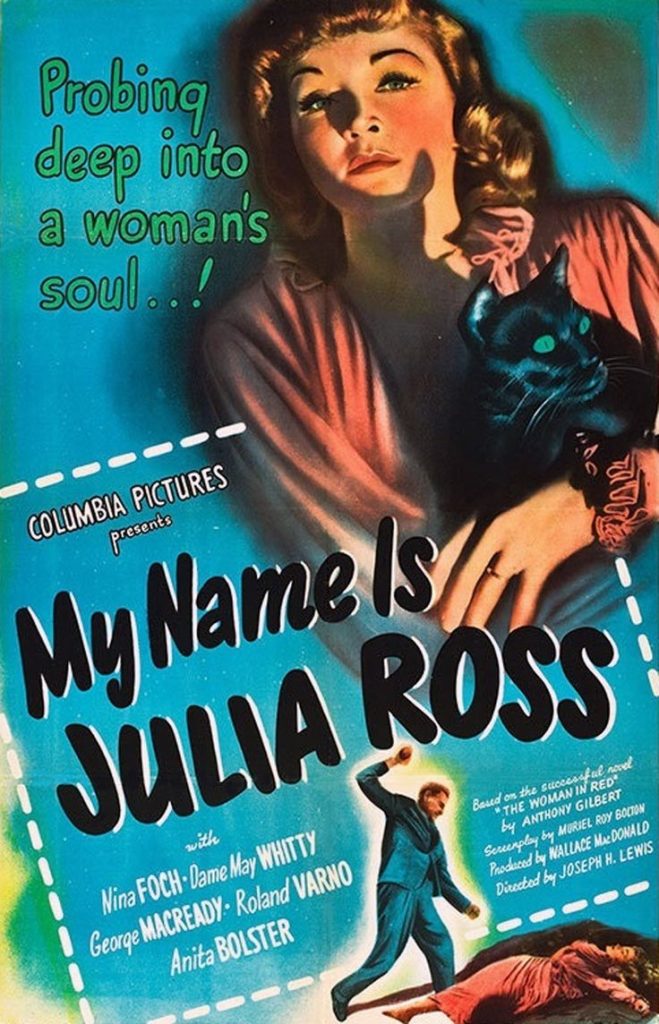

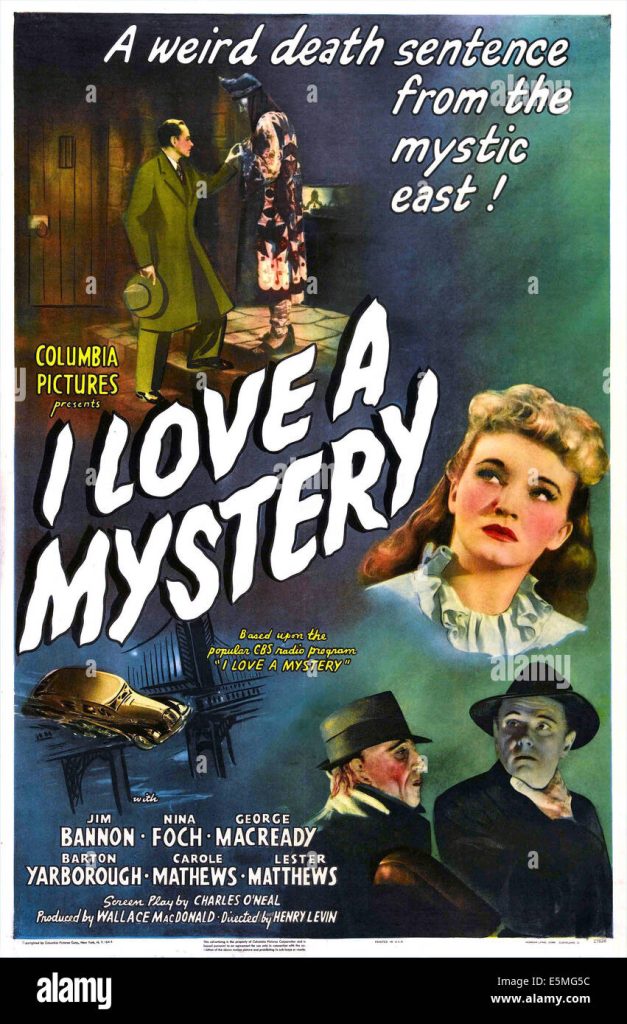

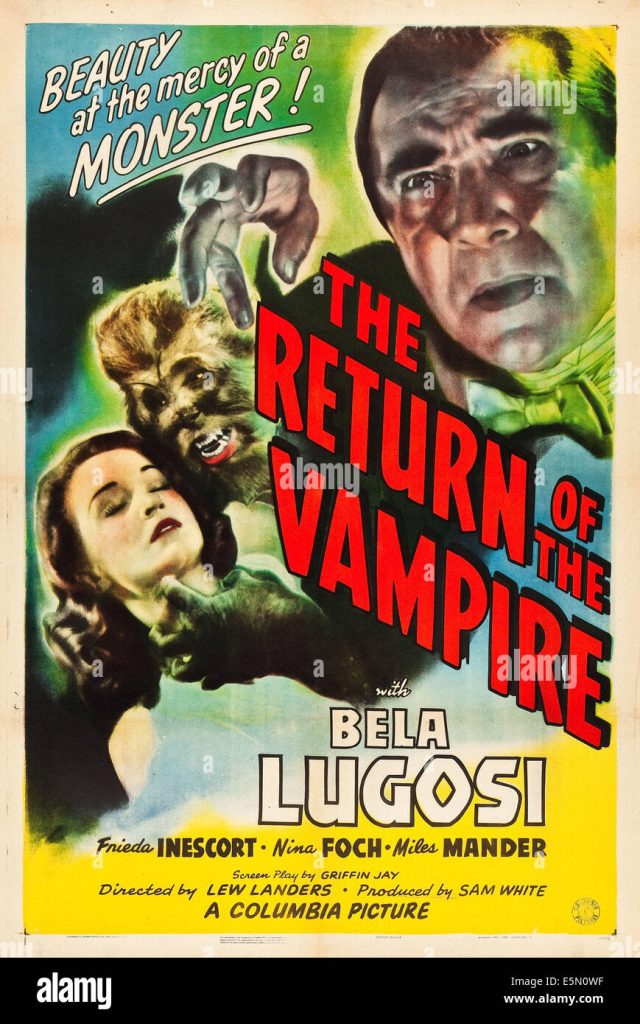

Foch, who was born Nina Consuelo Maud Fock in Holland, was brought up in New York. She was the daughter of Dutch composer-conductor Dirk Fock and American showgirl Consuelo Flowerton, famous from first world war posters. Her parents divorced when she was in her early teens. “He hated my mother sufficiently, my mother hated him. I was a pitiful child, an unloved child.” Consuelo, who was busy being a renowned beauty, told her daughter that she was “terribly awkward,” and sent her to the American Academy of Dramatic Arts to develop some poise. Later, in her acting career, poise was one thing she had in abundance. In 1943, aged 19, she was signed up by Columbia Pictures, who changed her name slightly, for obvious reasons. Her first two films were horror movies, Return of the Vampire (1943), in which she was a victim of bloodsucking Bela Lugosi, and top-billed in Cry of the Werewolf (1944) as Queen Celeste, the Gypsy queen who turns into a werewolf. The following year, she was in A Song to Remember, the Chopin biopic, as one of the leaders of the Polish revolutionary group for whom the composer writes a polonaise; and expressing vulnerability splendidly as an innocent woman caught in a sinister web of intrigue in Joseph H Lewis’s My Name is Julia Ross.

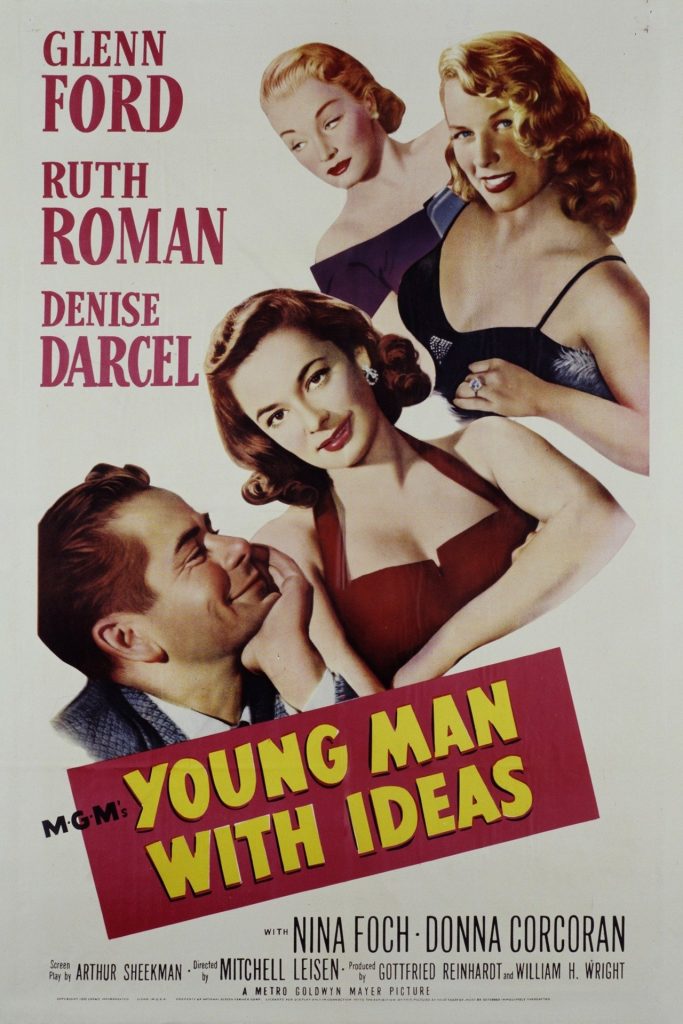

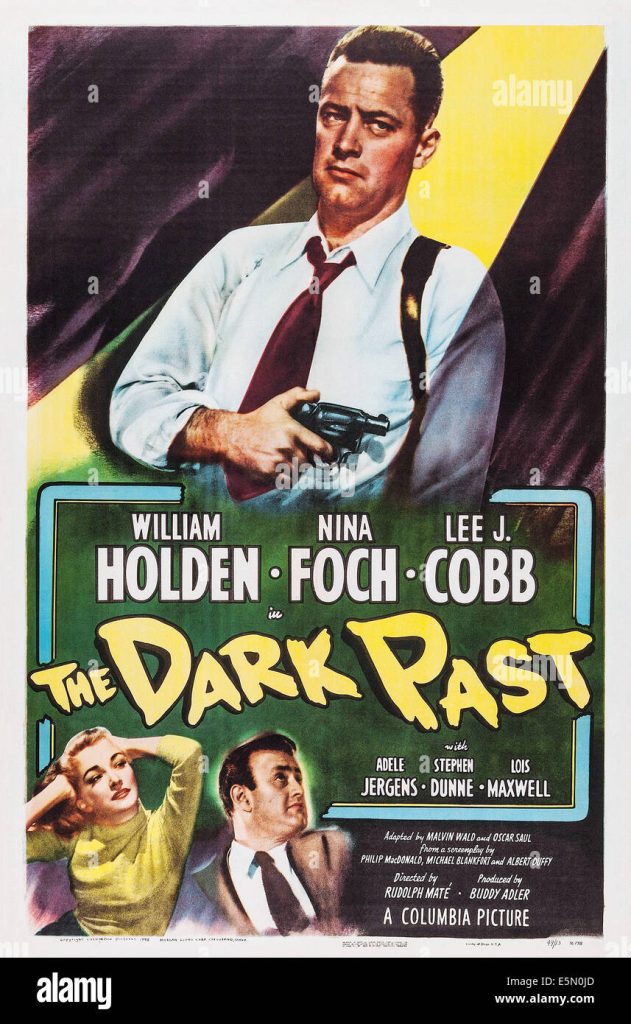

Foch continued throughout the 1940s at Columbia, most often in noirish roles. She was particularly effective as the tough and tender moll of William Holden in The Dark Past (1948); secret service man Glenn Ford’s wife in The Undercover Man (1949) and as a married siren getting her claws into ex-con George Raft in Johnny Allegro (1949). During her seven years at the studio she had to endure wounding comments from Columbia’s notorious boss, Harry Cohn, such as: “It’s a shame you’re not pretty. You don’t have any sex appeal.” At one stage, she argued with him to allow her to perform on television, a medium on which she would appear hundreds of times. He agreed, provided she paid Columbia half her salary, which she did for a year.

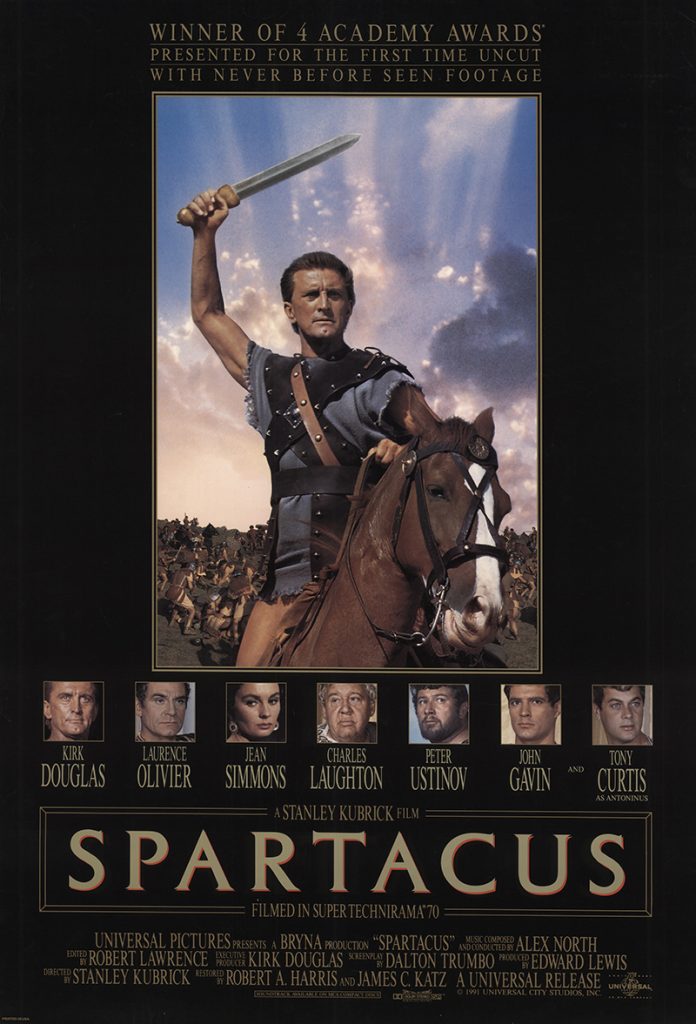

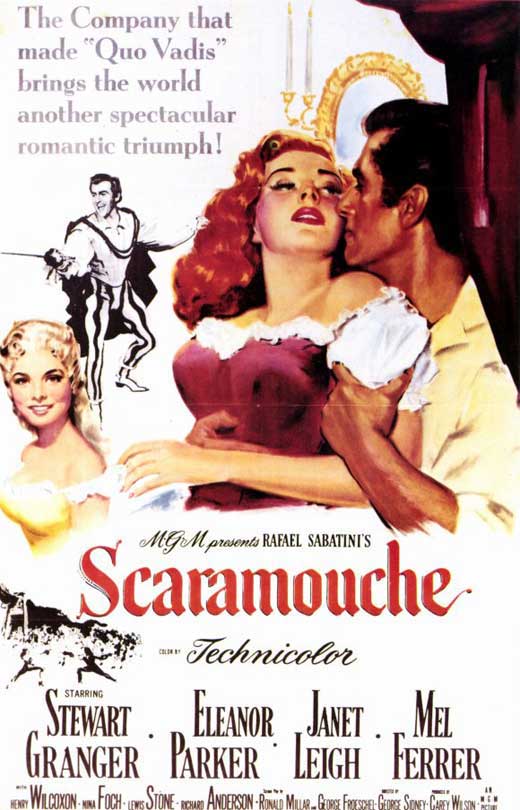

Foch left Columbia in 1950 for a short stay at MGM, where she made such an impact in An American in Paris; was a ravishing Marie Antoinette in Scaramouche (1952); played the wife in a loveless marriage with dying Vittorio Gassman in Sombrero (1952); and got nominated for a best supporting actress Oscar in Executive Suite (1954). In the last, her blonde hair in a severe bun, she holds the all-star cast together as the secretary mourning the death of her boss, and woefully overseeing the battle for his successor.

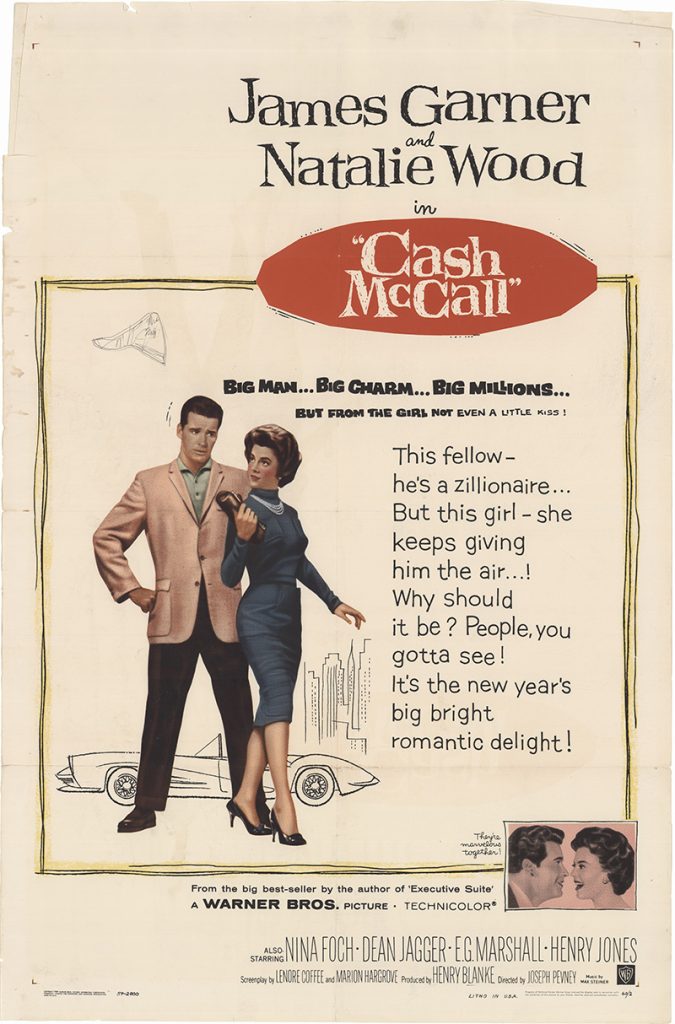

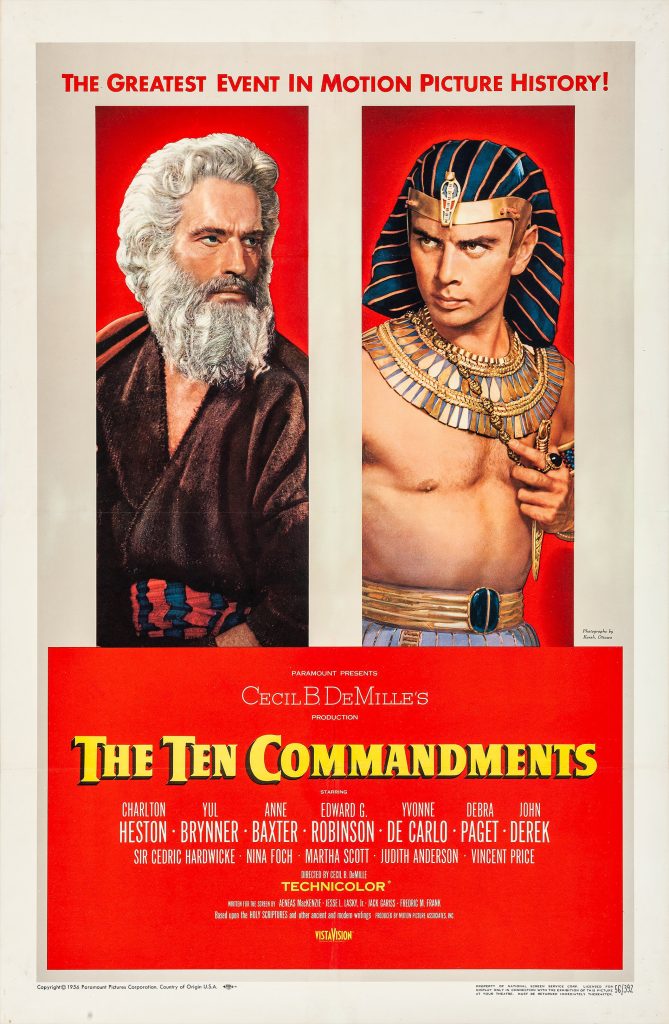

As a freelance, Foch was excellent as criminal lawyer Edward G Robinson’s assistant in Illegal (1955), who is defended by her superior after she has killed her crooked husband in self-defence. In Cecil B DeMille’s Ten Commandments (1956), she played Bithiah, who finds the baby (Charlton Heston’s infant son) in the bulrushes, names him Moses and brings him up as her own. She was back to being a smart woman of the world in Cash McCall (1960), making a play for businessman James Garner, in one of her last parts before retiring from the big screen for some years to become an influential drama teacher.

She had begun teaching film and drama at both the University of Southern California and the American Film Institute. Of any potential student, she would ask: “Why do you want to become an actor?” If they replied, “because I want to be a star,” she would reject them, telling them to return when they found the correct answer. In later years, she ran her own script-doctoring studio in Hollywood. At the same time, Foch had guest spots on many television series, winning an Emmy nomination for a stint on Lou Grant. In her 70s, she made a feature film comeback of sorts, but neither the parts nor the pictures were much good.

In recent years, she expressed horror at the “viciousness” she saw in Hollywood. “I salute the people who have the gristle to manage it,” she commented, “to be actors in this day and age and put up with the way they’re treated. You have a choice, you either get afraid, or you get so afraid that you’re angry. It is that anger, that rage, that saved my life, I think.”

Foch, who was married and divorced three times (her first husband was James Lipton, known mainly as the host on TV’s Inside the Actors Studio), is survived by a son.

• Nina Foch, actor, drama teacher, born April 20 1924; died December 5 2008