Anthony Perkins obituary in “The Independent” in 1992.

It happens on occasion, paradoxically, that an actor or actress must strive to ‘live down’, not a poor performance, but a great one.

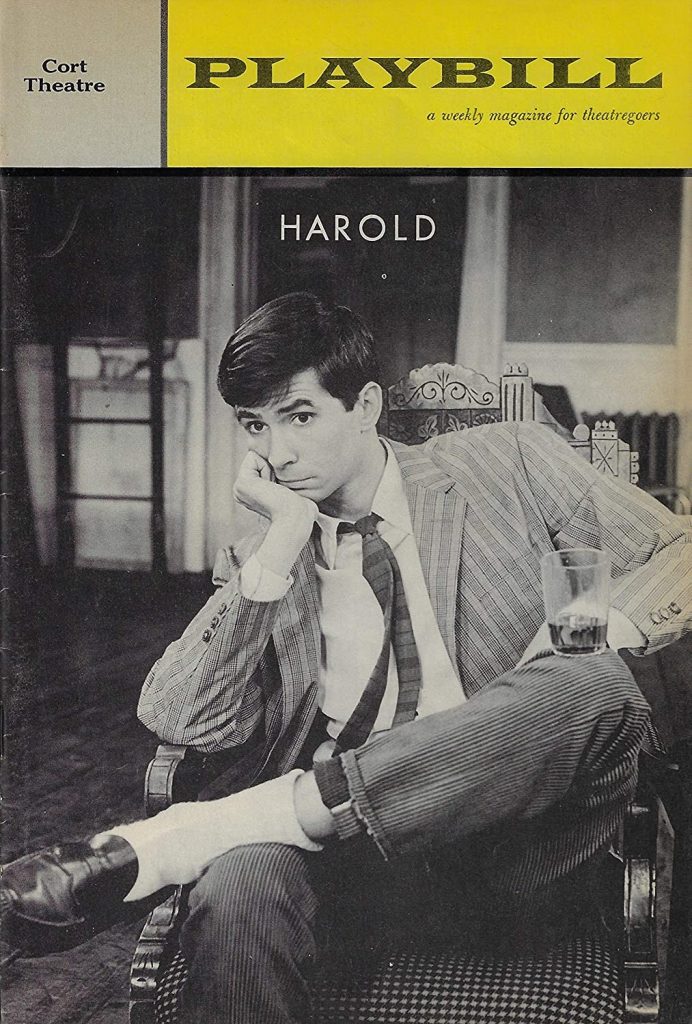

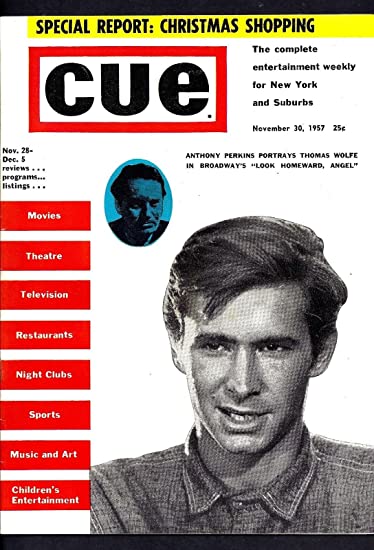

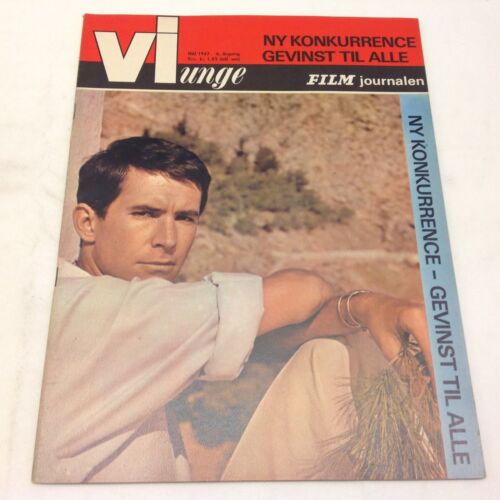

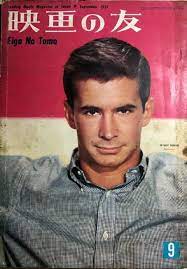

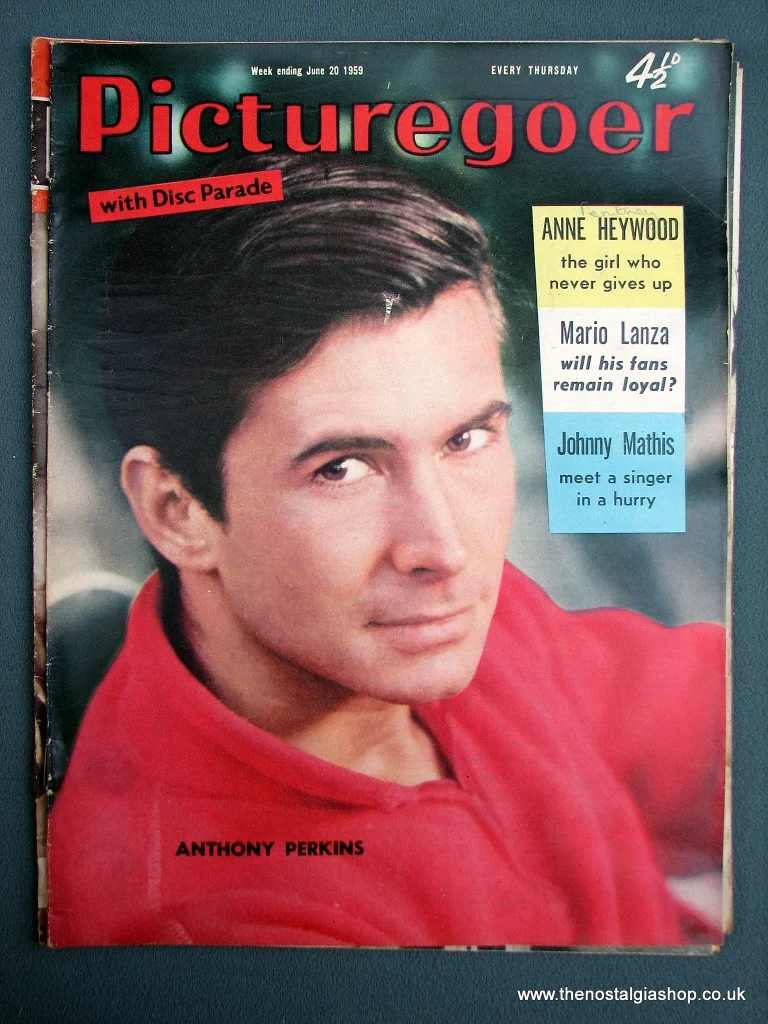

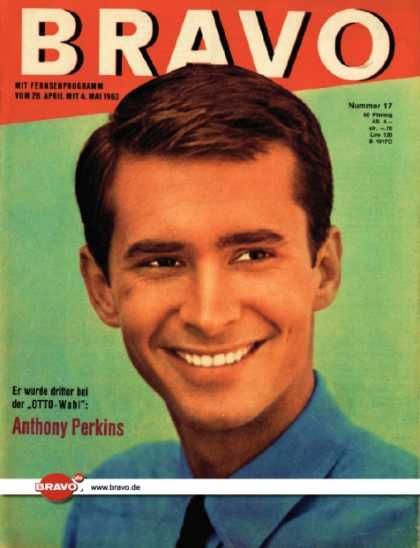

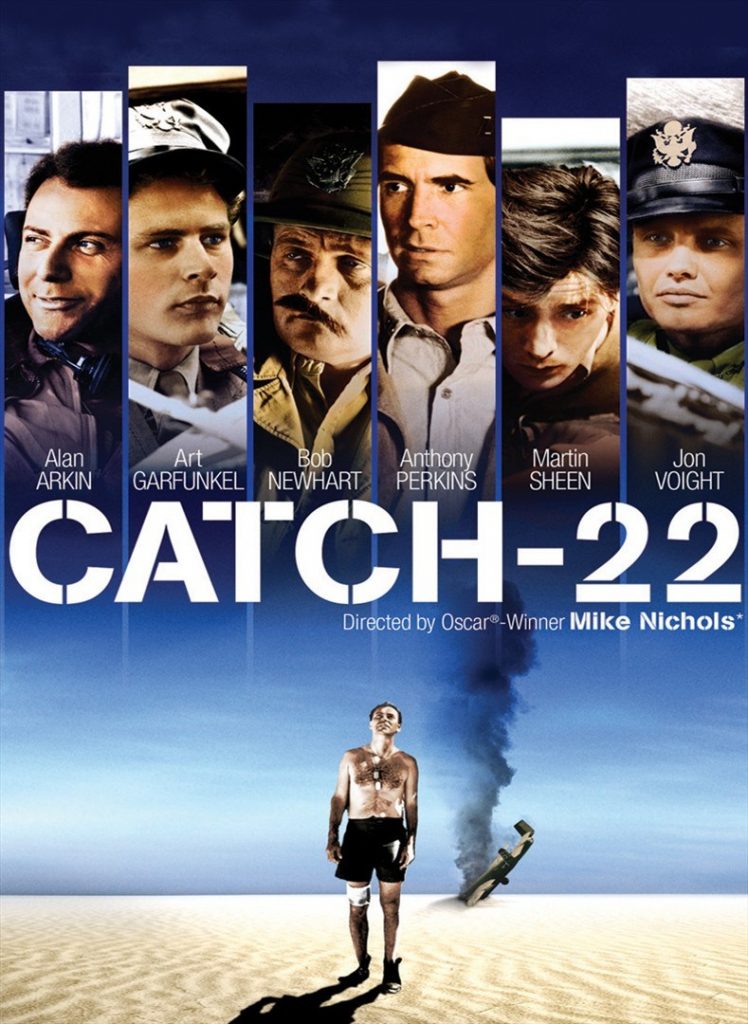

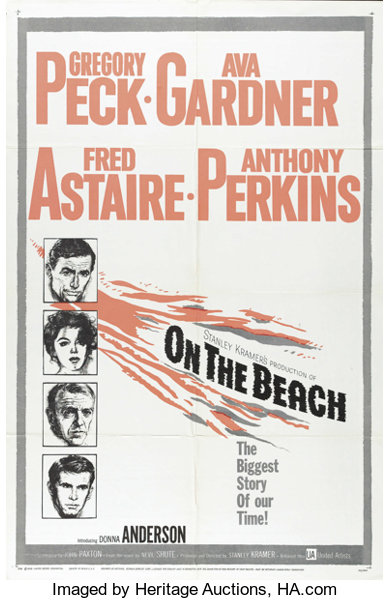

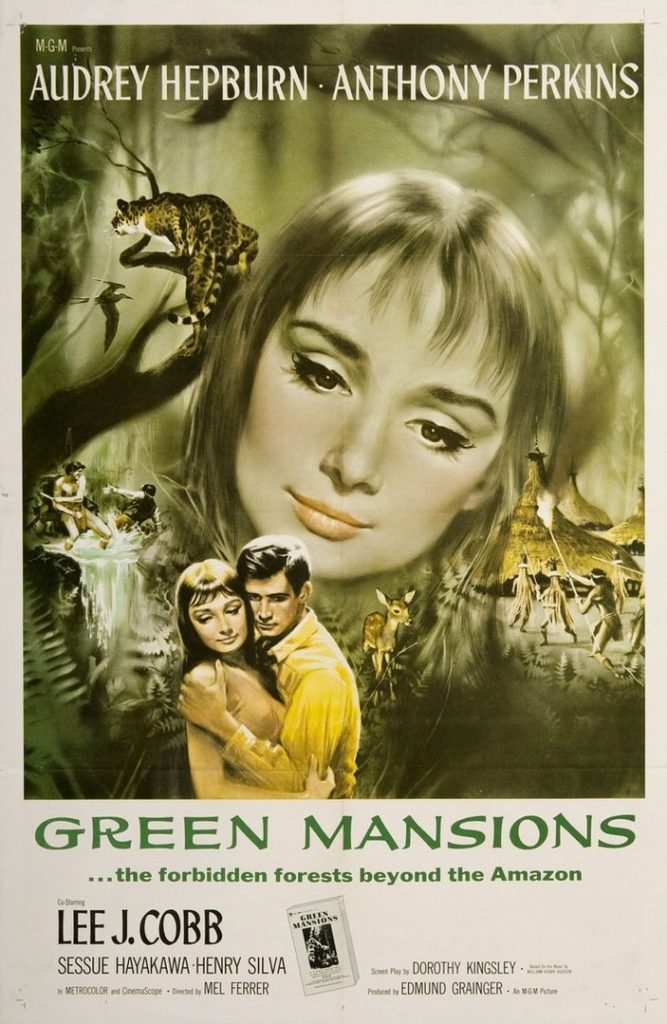

Anthony Perkins (who was the son of a once celebrated stage and screen actor, Osgood Perkins) had played gangling, sensitive young men, of a sometimes almost neurotic febrility, in a number of films before being offered the leading role in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho in 1960.

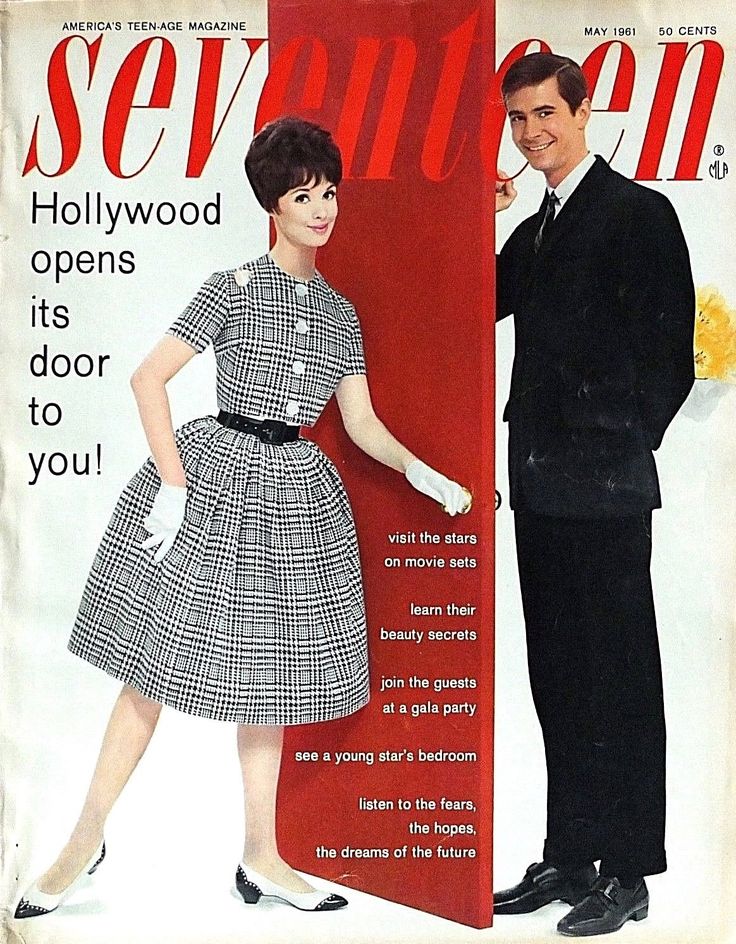

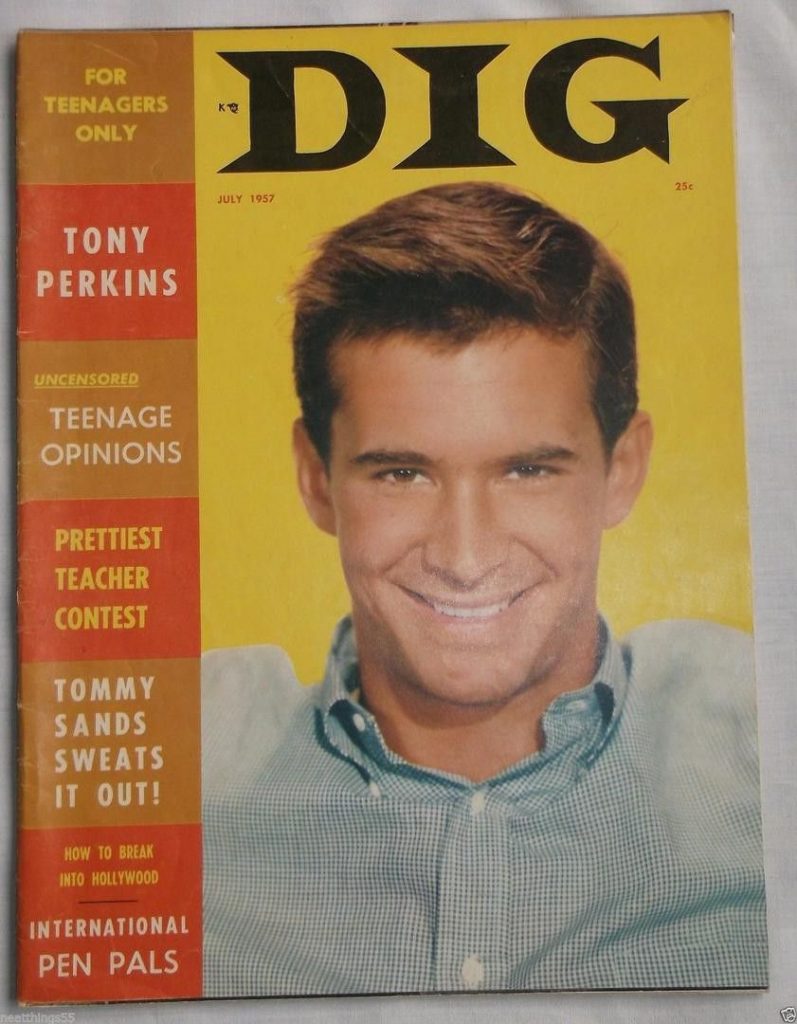

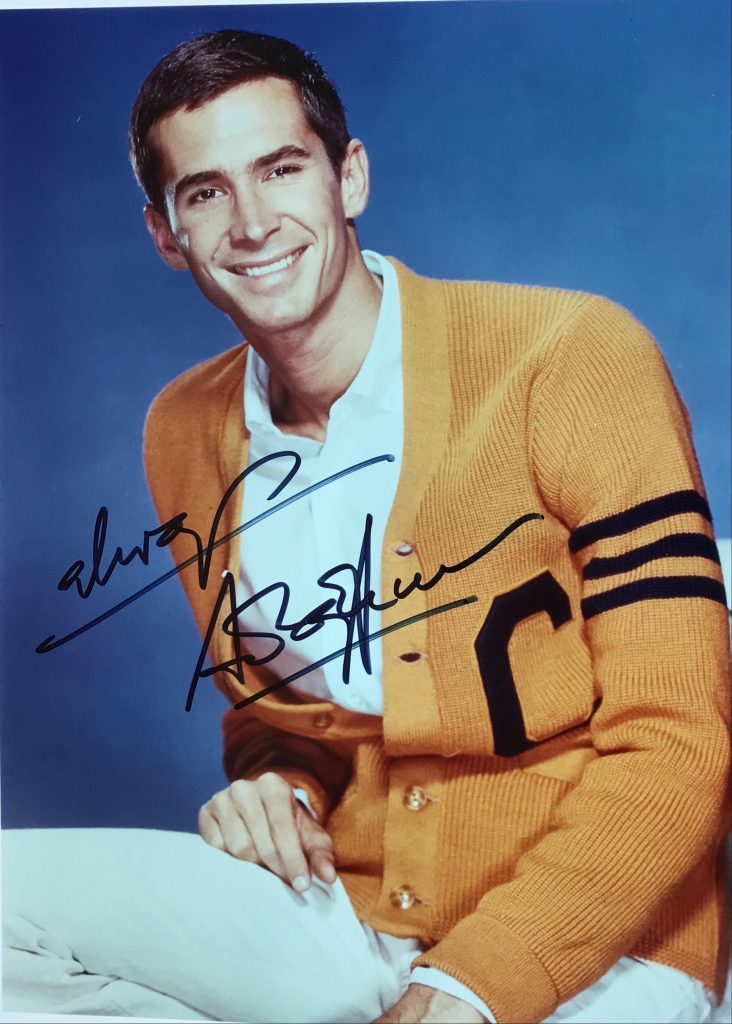

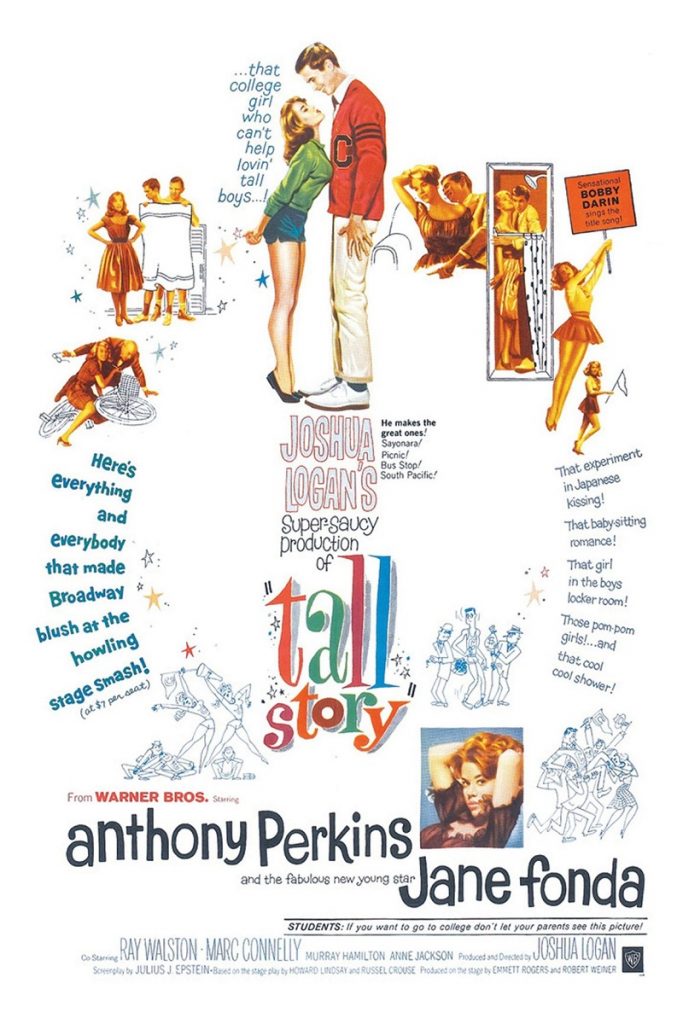

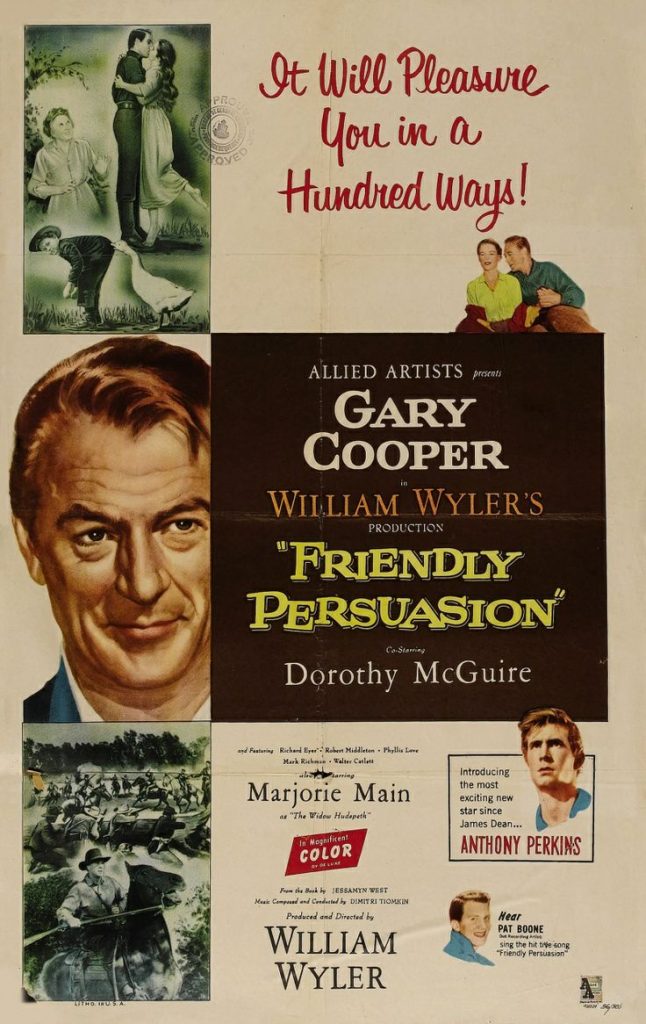

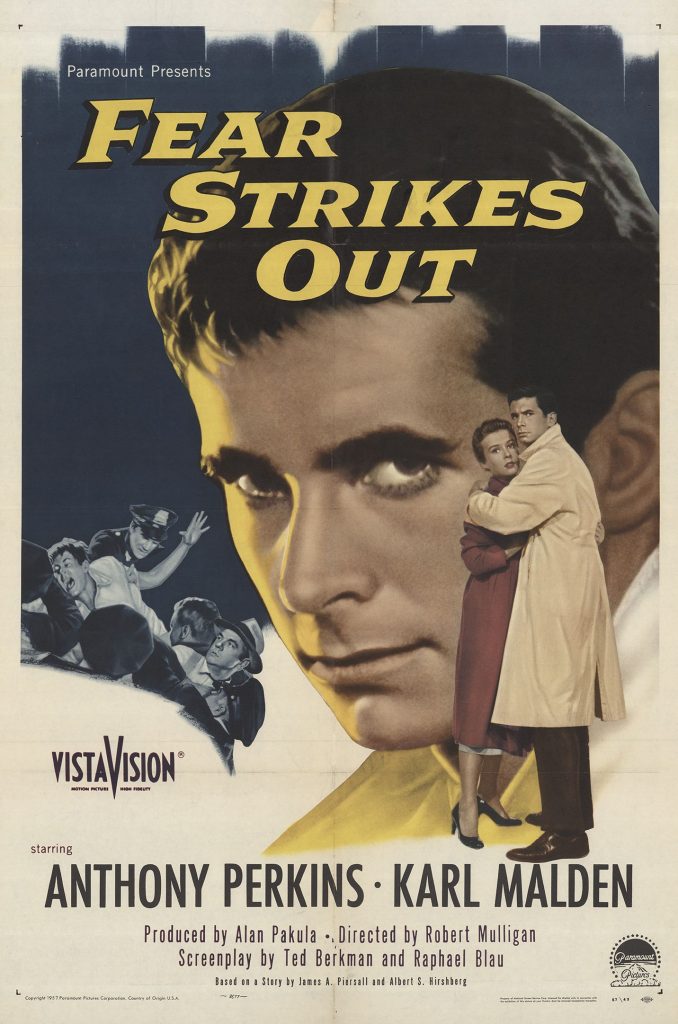

He was Jean Simmons’s boyishly bashful beau in George Cukor’s The Actress (1953), the son of Quaker parents (Gary Cooper and Dorothy McGuire) in William Wyler’s Friendly Persuasion (1956), a mentally disturbed baseball champion in Robert Mulligan’s Fear Strikes Out (1957) and a delightfully leggy college athlete in Joshua Logan’s Tall Story (1960), which cast him opposite a no less youthful and sexy Jane Fonda.

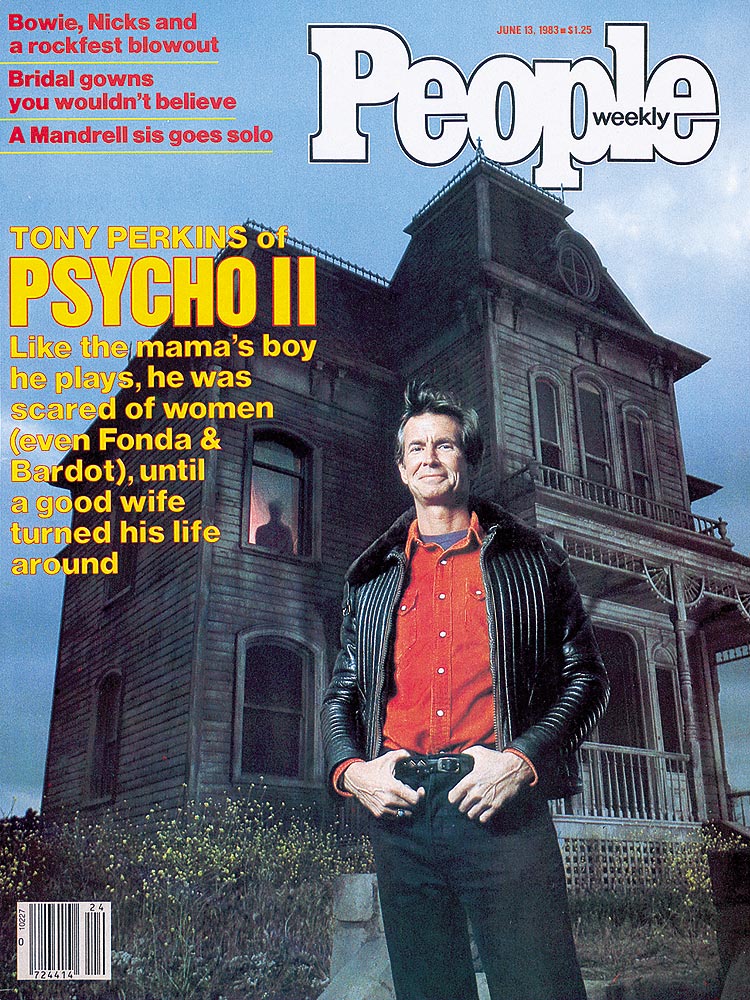

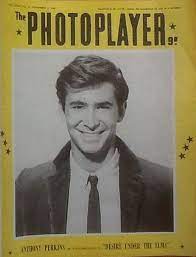

But it is as Norman Bates, the psychopathic motel-keeper of Hitchcock’s masterpiece, that he will ever be remembered. So much so, indeed, that just as Norman was to identify with his deceased mother in a gruesomely literal sense, the actor would become – to the detriment, it has to be said, of his subsequent career – much too closely identified with the character whom he created. Beyond its unique crossbreeding of cutely callow puppyishness and sudden, wittily sinister malevolence, what makes Perkins’s performance one of the most amazing in the history of the cinema, and quite as worthy of study and analysis as the film which enshrines it, is perhaps its intense physicality.

Though less than those from television, film stars have a tendency to be perceived as oddly disembodied beings – with enormous, screen-filling heads perched on bodies that, for most of the time, remain inexpressive and virtually invisible. In the case of Norman Bates, by contrast, the striking angularity of Perkins’s physical frame and the cunning way in which it was played against his coltish, soft-spoken, almost homespun manner, engendered what the French term a portrait en pied, a full-length portrait. And it is a measure of Perkins’s presence and authority that ‘Norman Bates’ is one of the relatively few fictional names that we recall from the medium (since most filmgoers will identify less readily with characters than with the actors who play them).

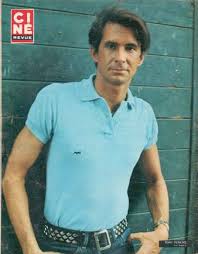

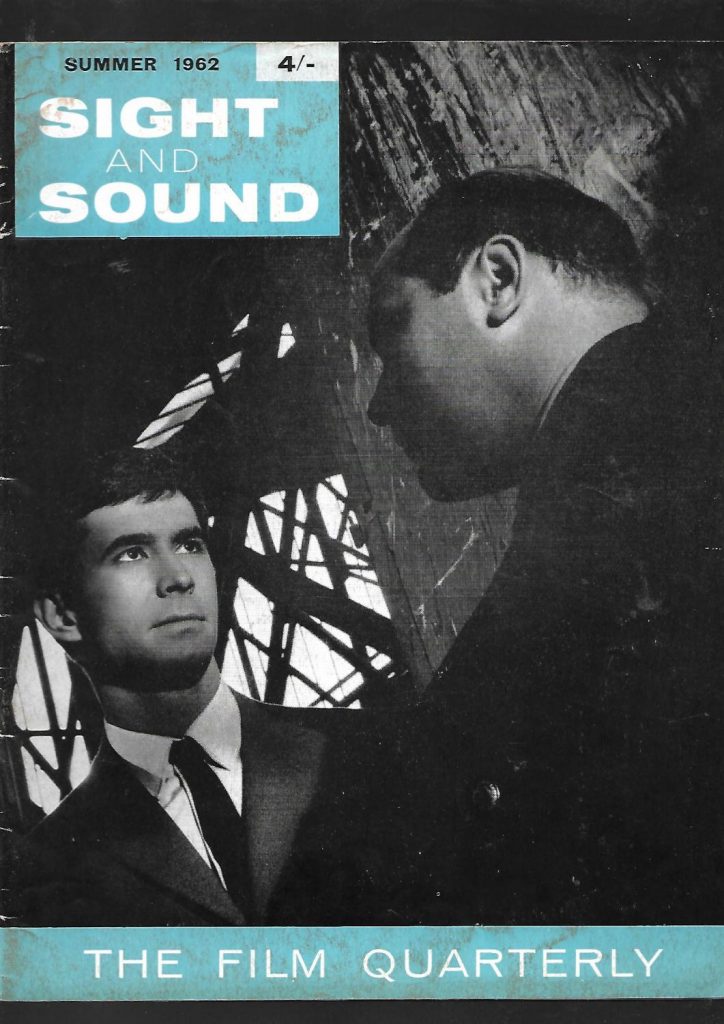

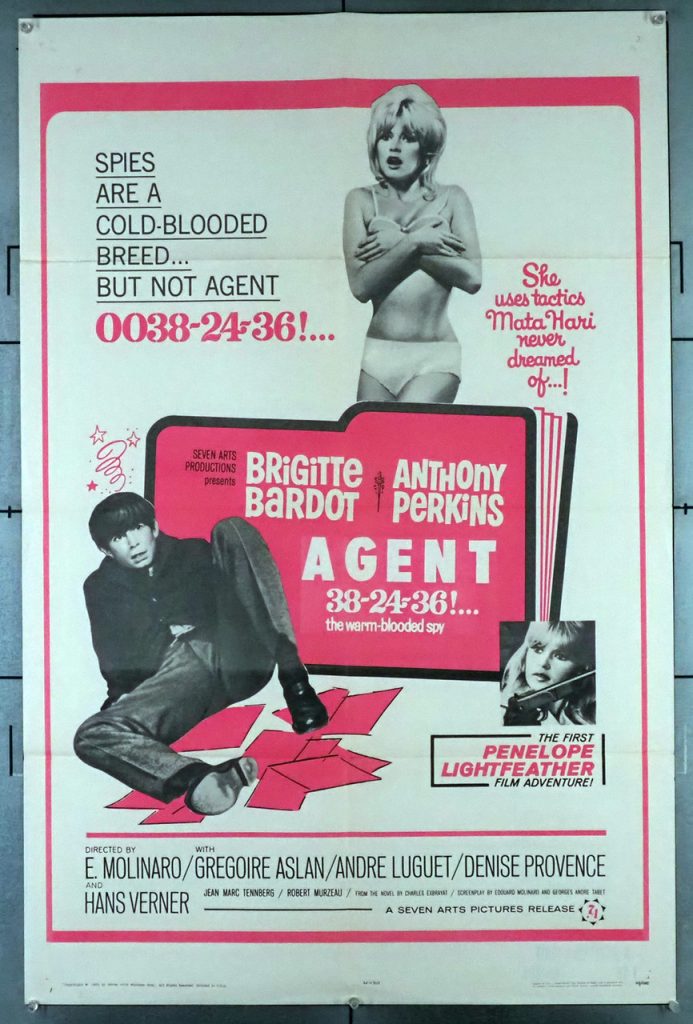

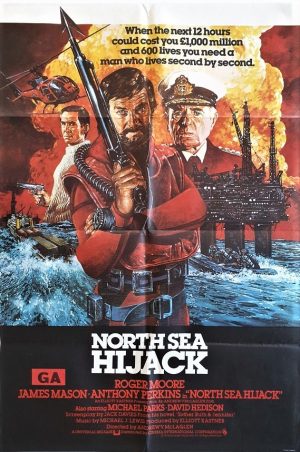

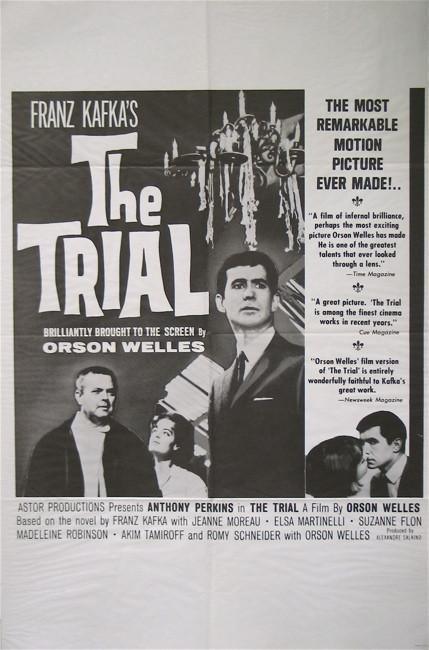

Following his rise to prominence in the wake of Hitchcock’s thriller Perkins settled in Europe, where he worked on a rather weird job lot of films. He appeared ill-at- ease as Ingrid Bergman’s toy boy in Goodbye Again, the turgid adaptation which Anatole Litvak made in 1961 of Francoise Sagan’s Aimez-vous Brahms? (one French critic’s review consisted simply of a sardonic, two-word response to the question – ‘Brahms, oui]’) and was quite ludicrous, like every other member of the cast, in Jules Dassin’s ill-advised updating of Racine’s Phaedra (1962). Though he made an eerily plausible, buttoned-up Joseph K in Orson Welles’s The Trial (also from 1962), the film itself, unfortunately for him, was a bloated monstrosity, one of Welles’s feeblest. And his two whodunits for Claude Chabrol, Le Scandale (1967) and La decade prodigieuse (1972), were also among the least distinguished efforts of that uneven director’s output.

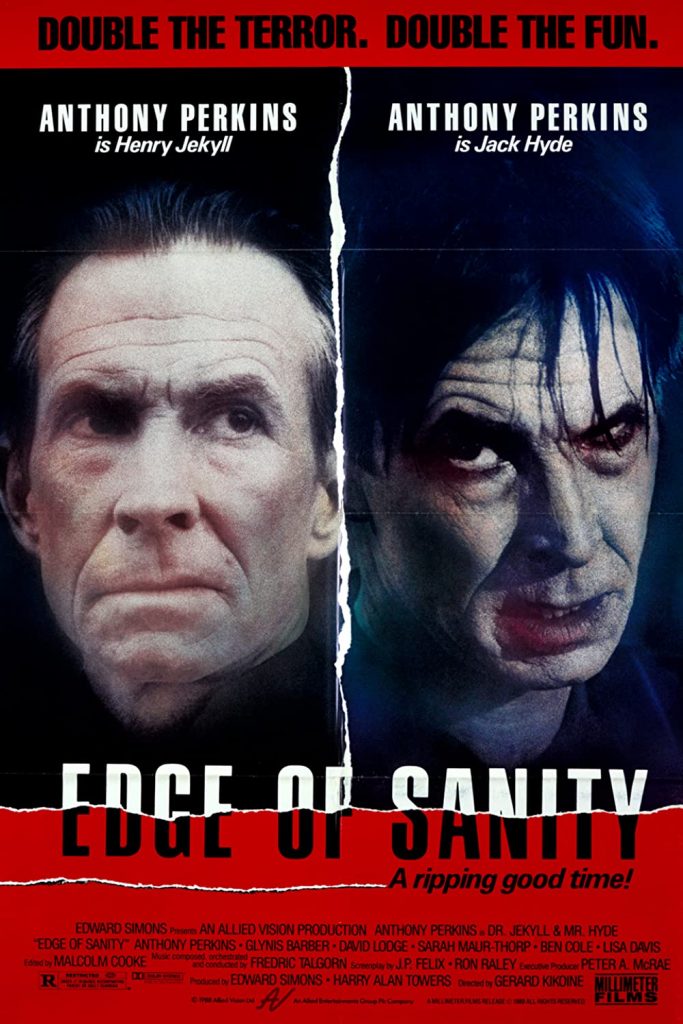

Even more dispiritingly, he began to accentuate the tics of his most famous role (the mobile left eyebrow that would contrive to steal every scene from the rest of his face, the pulsating vein in his neck), eventually reprising it in three dire, Hitchcock-less sequels, the second of which, Psycho III (1985), he directed himself.

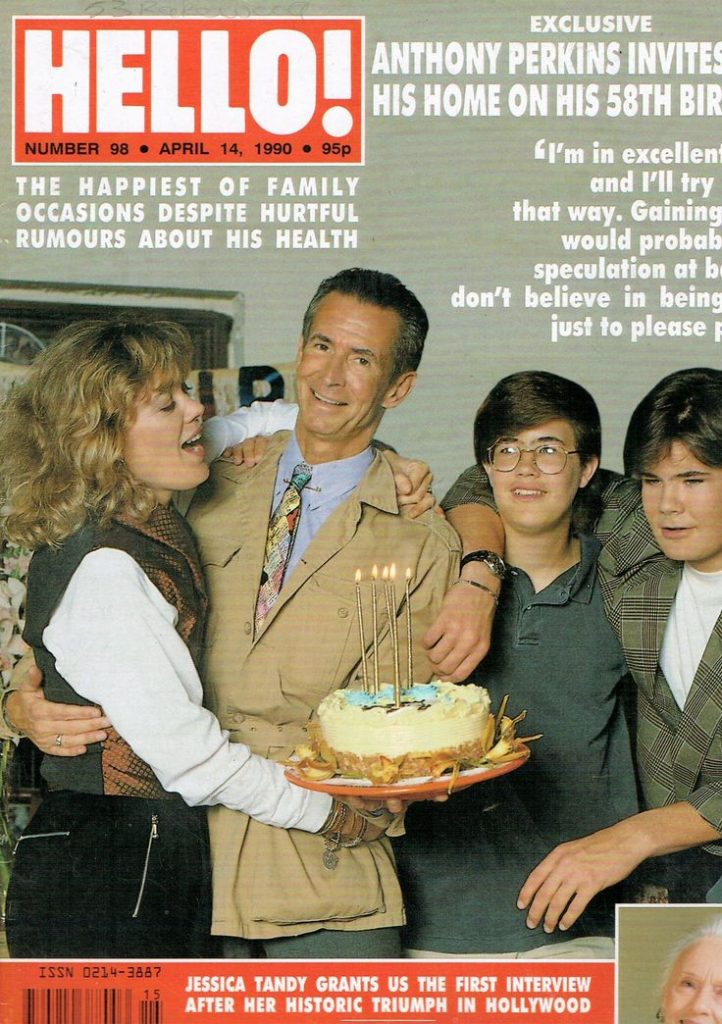

Perkins, significantly, admitted to having been long dominated by his own mother, much like Norman; and it was not until 1973, when he was 41, that he married Berinthia (Berry) Berenson, sister of the model and sometime actress Marisa and granddaughter of the art collector Bernard. Before that, as he publicly confessed, ‘I never had sex with a woman – the thought terrified me.’

At least in a certain milieu, however, his homosexuality was an open secret; and even if there was no hint of that particular deviation in Norman Bates’s make-up, it too no doubt contributed to the aura of psychosexual ambiguity which enhaloed the evil and disquieting alter ego who haunted him until the end of his life.