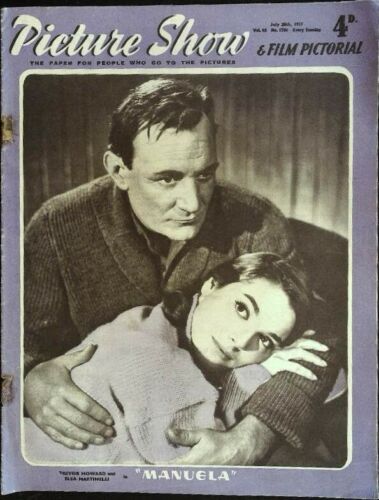

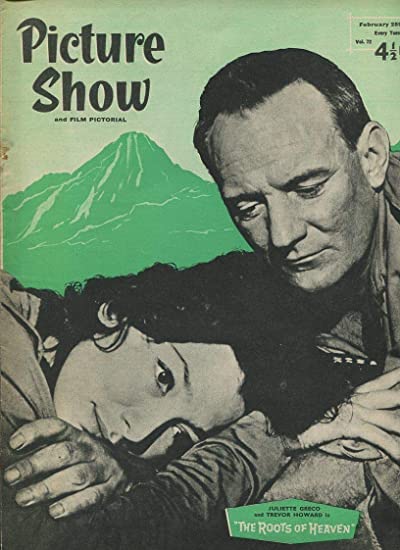

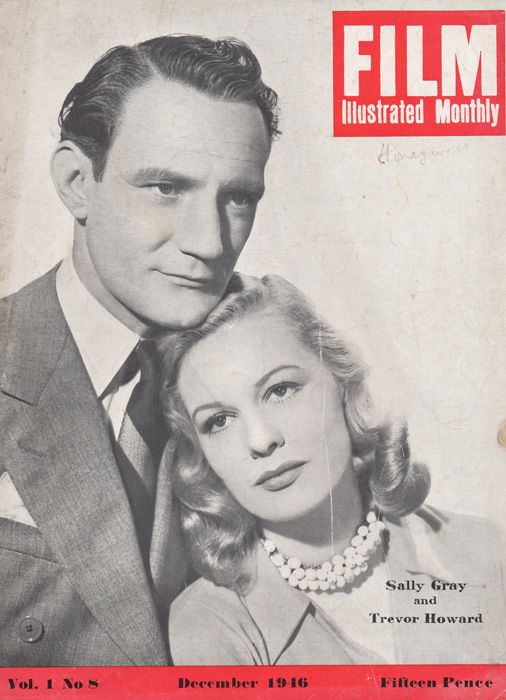

Trevor Howard article in “Telegraph” in 2001.

Trevor Howard was convicted three times for drink-driving offences, and on one occasion was banned from driving for eight years. Upon landing in Kenya to shoot one of his final films, White Mischief, he was so befuddled with alcohol that he had to be met with a wheelchair.

He was retained in the cast only because his co-star, Sarah Miles, told the producer: “If he goes, I go, too.” She took personal charge of getting him in a fit state to go before the cameras.

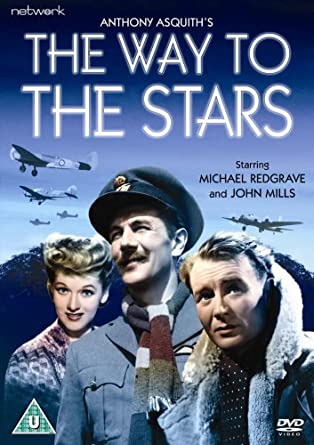

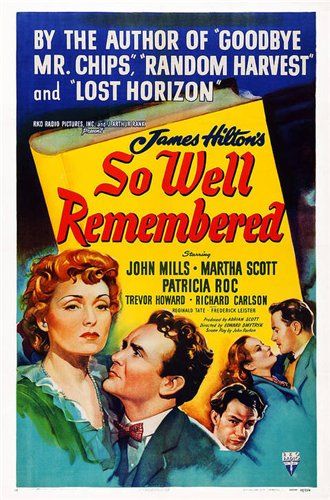

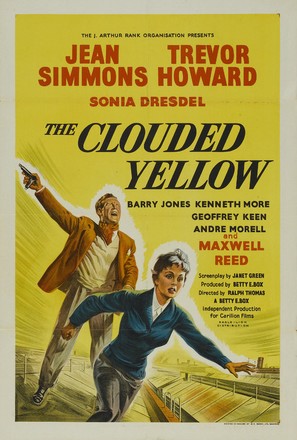

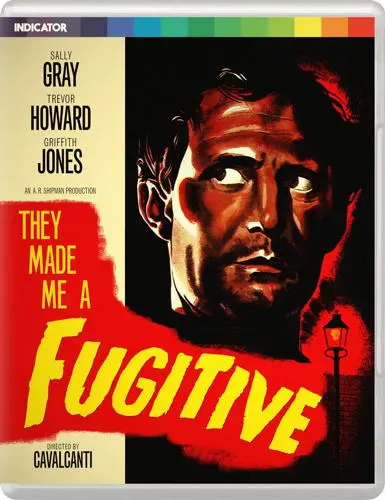

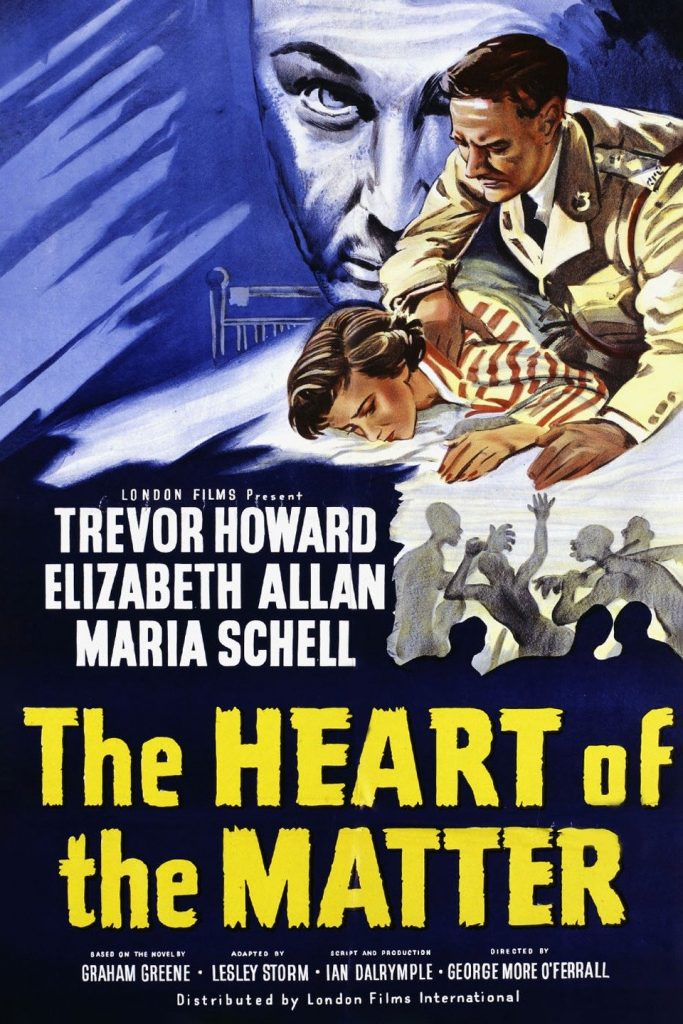

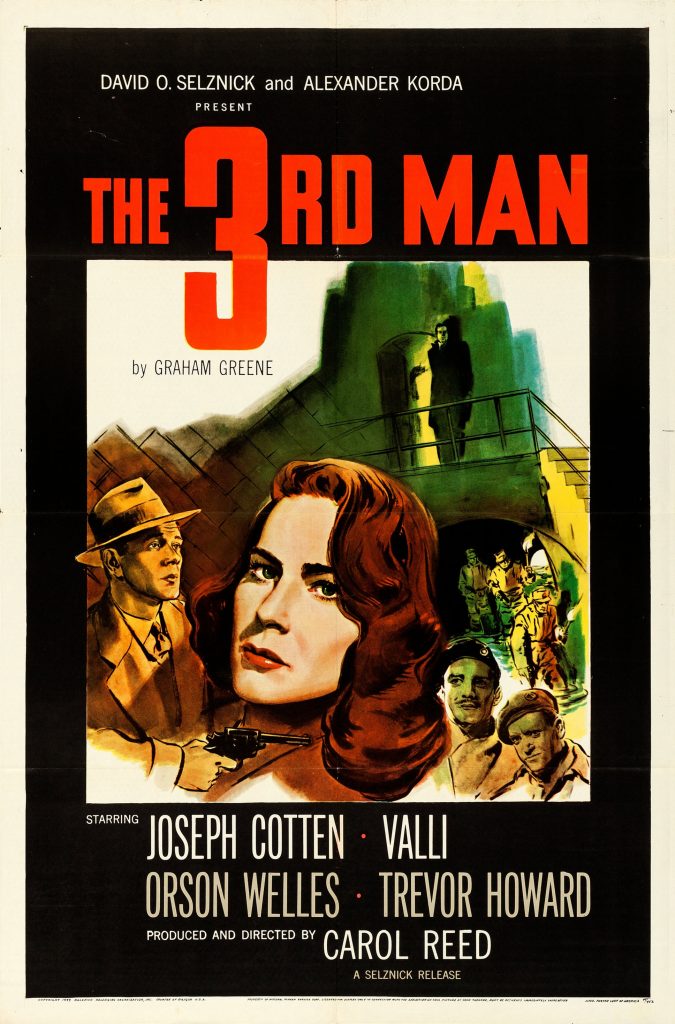

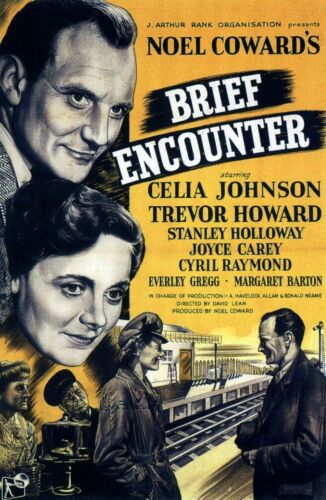

Yet, however drunk he had been, such as during the shooting of another movie, Cockleshell Heroes, when he had to have “several cups of the strongest coffee available outside Turkey” poured down his gullet, once on the set – according to a production assistant – “He was word perfect. You’d think he’d been up half the night learning his lines.” That professionalism won him starring roles in two of the greatest pictures of British cinema’s golden era, Brief Encounter and The Third Man.

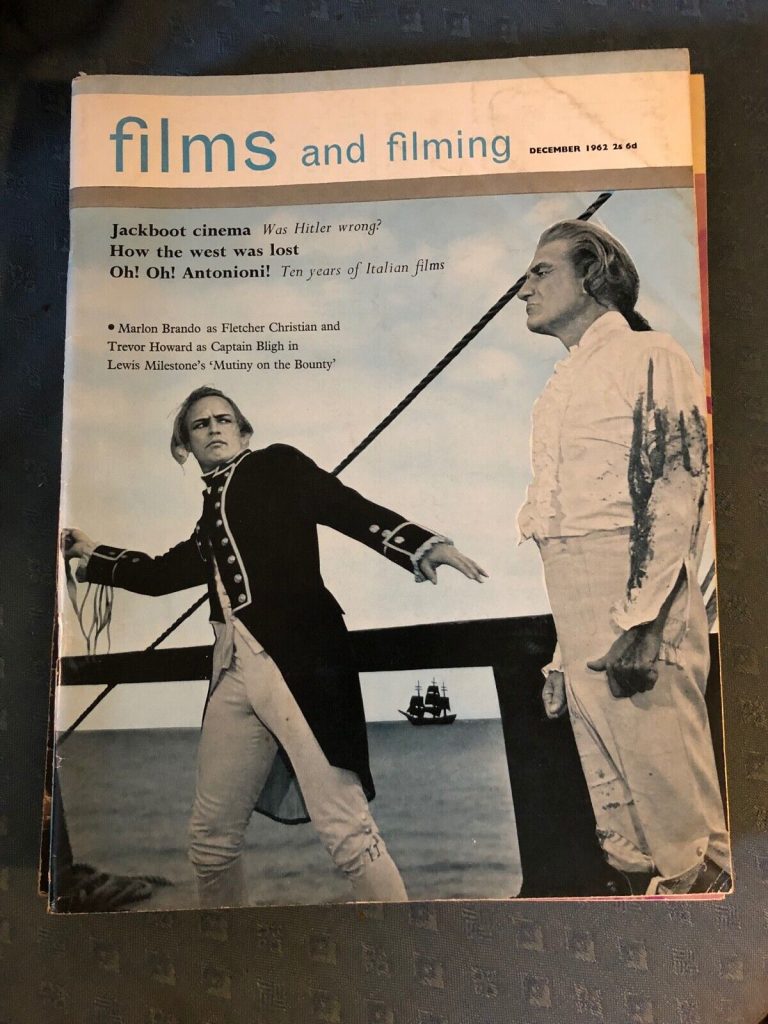

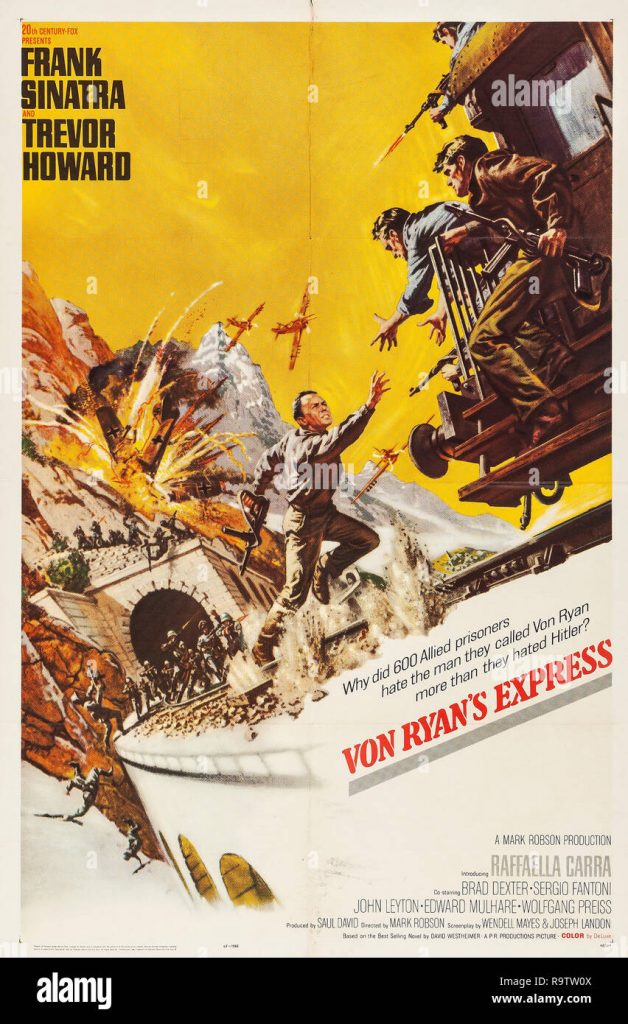

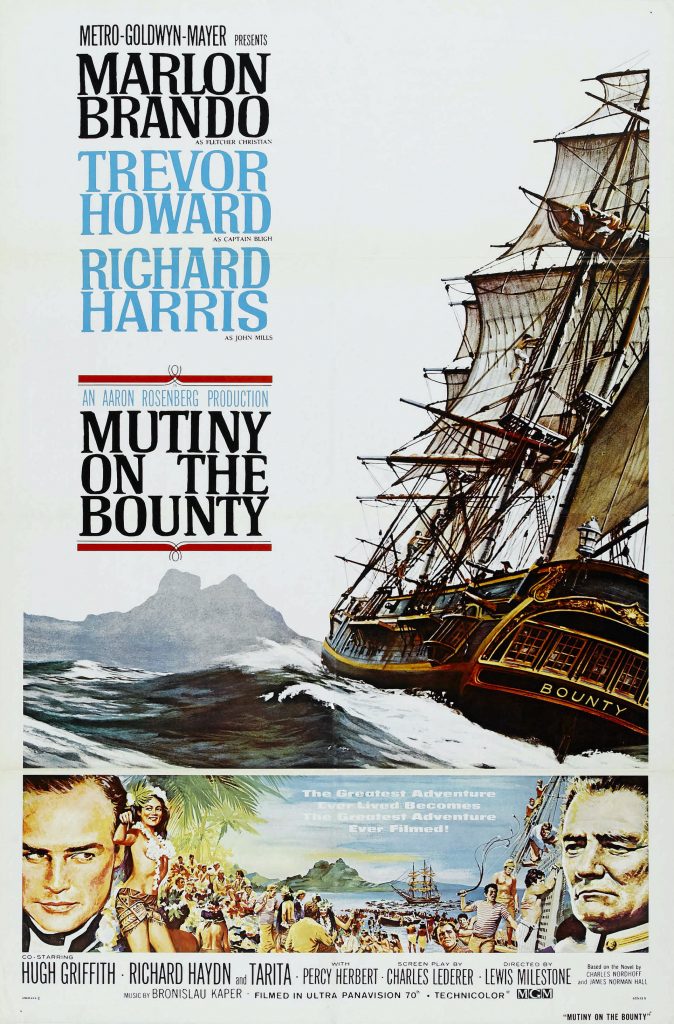

Howard was contemptuous of temperamental super-stars he filmed with. Of Marlon Brando, he snorted: “Look at him! He’d want two million to read the nine o’clock news!” He was filled with scorn when Frank Sinatra’s staff, on location in Italy, “emptied all the juke boxes in all the cafes and filled them with Sinatra records”.

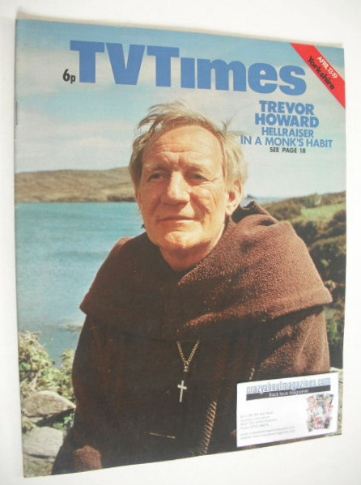

Howard was a dedicated and accomplished liar. His pose as a Second World War hero was so persistent and convincing that obituaries on his death in 1988 perpetuated the fiction he had fostered sedulously that he was a battle-scarred hero whose dare-devil exploits in Norway and Sicily won him the Military Cross.

In fact, he did his best to dodge the call-up and, after having been conscripted, was kicked out of the forces in mysterious circumstances which remain unfathomed despite the painstaking researches by the author of this book. Howard lied about his background, from his schooldays onward, so determinedly that War Office records described him as “suffering from psychopathic personality”.

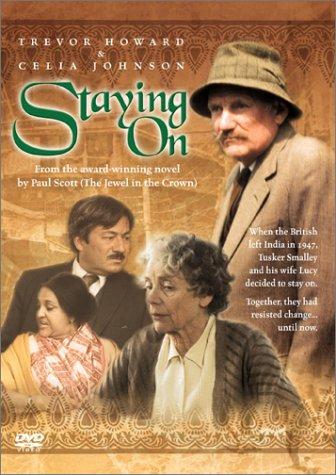

Yet in his films this same Howard (or Trevor Howard-Smith as he was really named) came to be seen as the tweed-jacketed, pipe-smoking epitome of middle-class respectability, whose role as a conventional doctor in Brief Encounter (for which he was paid £500 as compared with £12,000 for his co-star, Celia Johnson) showed him failing to commit adultery in a passionate but unconsummated affair conducted to the music of Rachmaninov.

Howard himself could not understand such prudish sensitivity. Waiting to shoot the film’s scene of embarrassingly thwarted seduction, Howard expostulated: “What’s all this about the rain and the fire not starting and the damp wood? Why doesn’t he just get stuck in?”

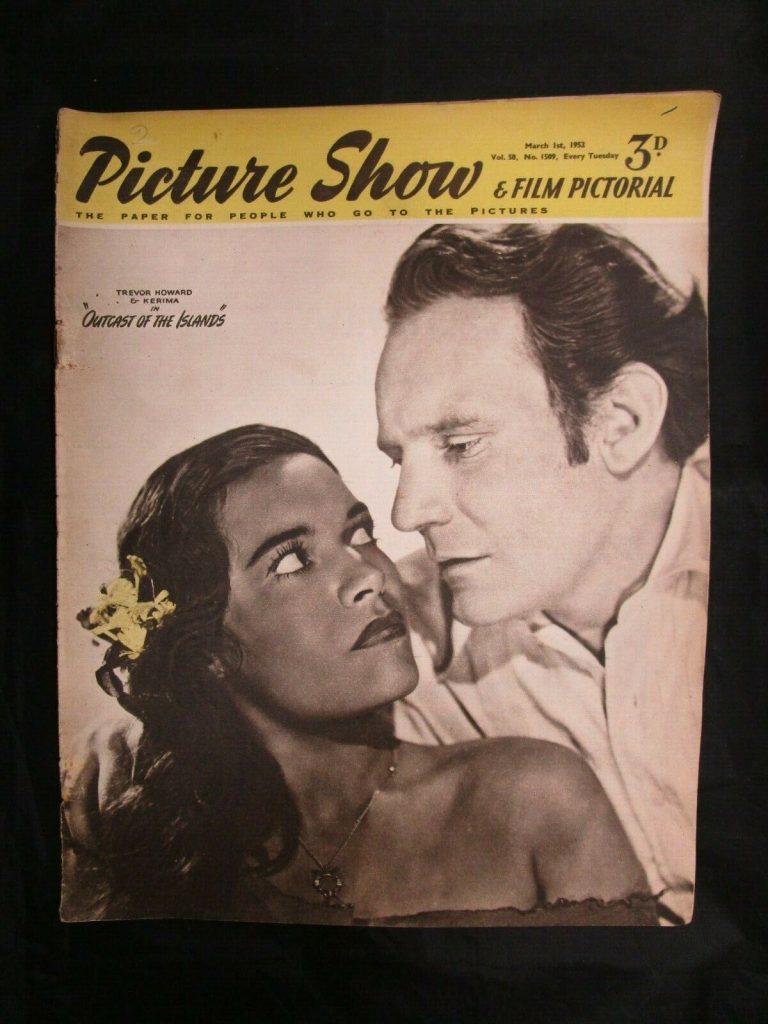

In real life, Howard certainly got stuck in. Although married for 43 years to the actress Helen Cherry, he was an incorrigible womaniser. An especially close liaison was with Anouk Aimee, his French teenage co-star in The Golden Salamander. Trevor Pettigrew reports coyly: “They were seen in a hotel late at night, evidently not rehearsing their lines.”

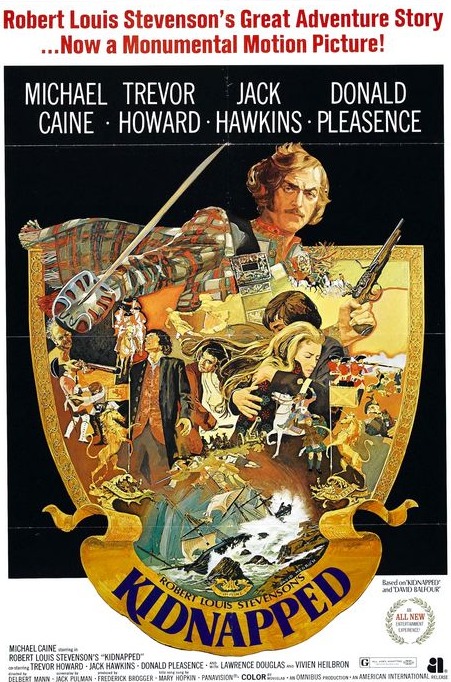

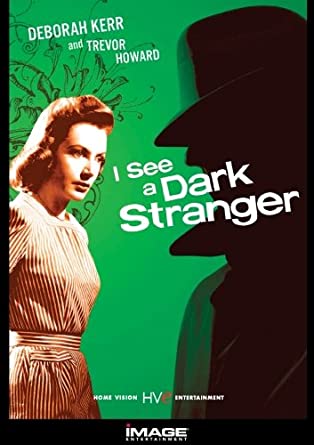

Pettigrew’s is a far from perfect biography. He fills page after dreary page with minute descriptions of his subject’s less-than-noteworthy sporting activities at Clifton College (although Howard claimed falsely, in publicity for his film I See a Dark Stranger, to have “captained the rugby and cricket teams”).

On the other hand, Howard’s genuine passion for sport won him a notable role in a West End play, a revival of Strindberg’s The Father. Witnessing his distress over England’s adverse fate in a Test match at Lord’s, the producer recalled: “I glanced at him, and saw that magnificent profile looking so agonised, so persecuted. I thought right away: That’s who we’re looking for! That’s the Father.”

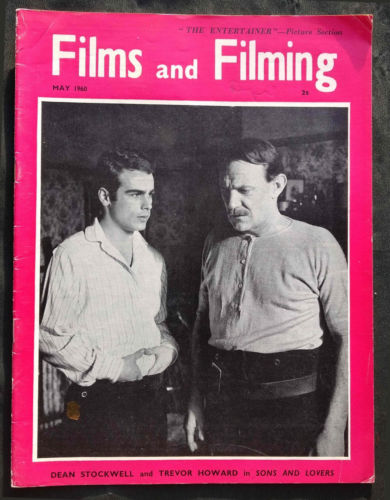

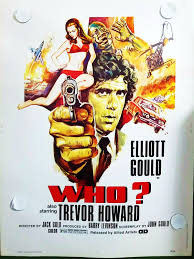

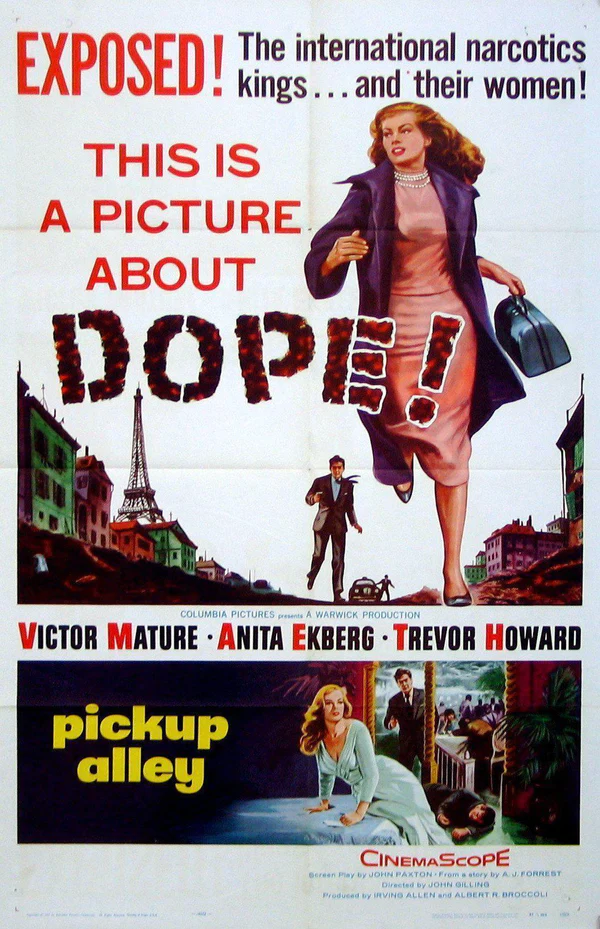

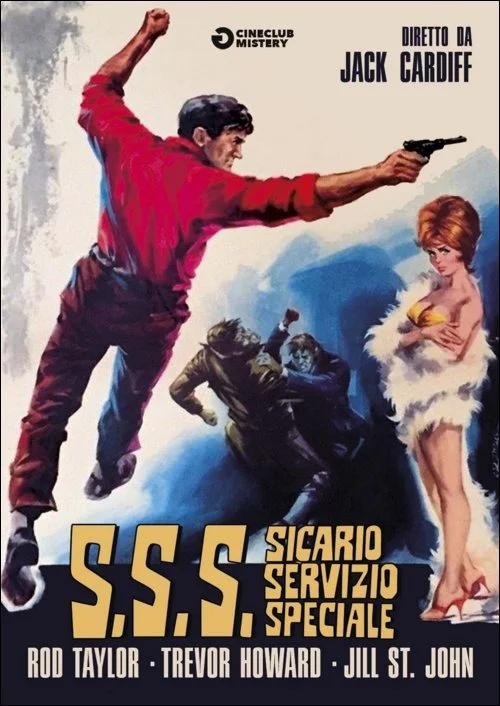

No wonder Richard Attenborough paid tribute to Howard for setting “a standard for reality and truth”. No wonder Howard made 76 films in 45 years, and was sufficient of a box-office draw right to the end that he left £3 million to his devoted and long-suffering wife.