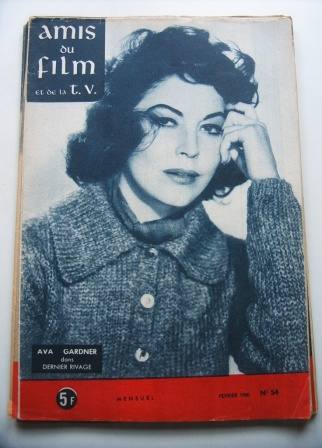

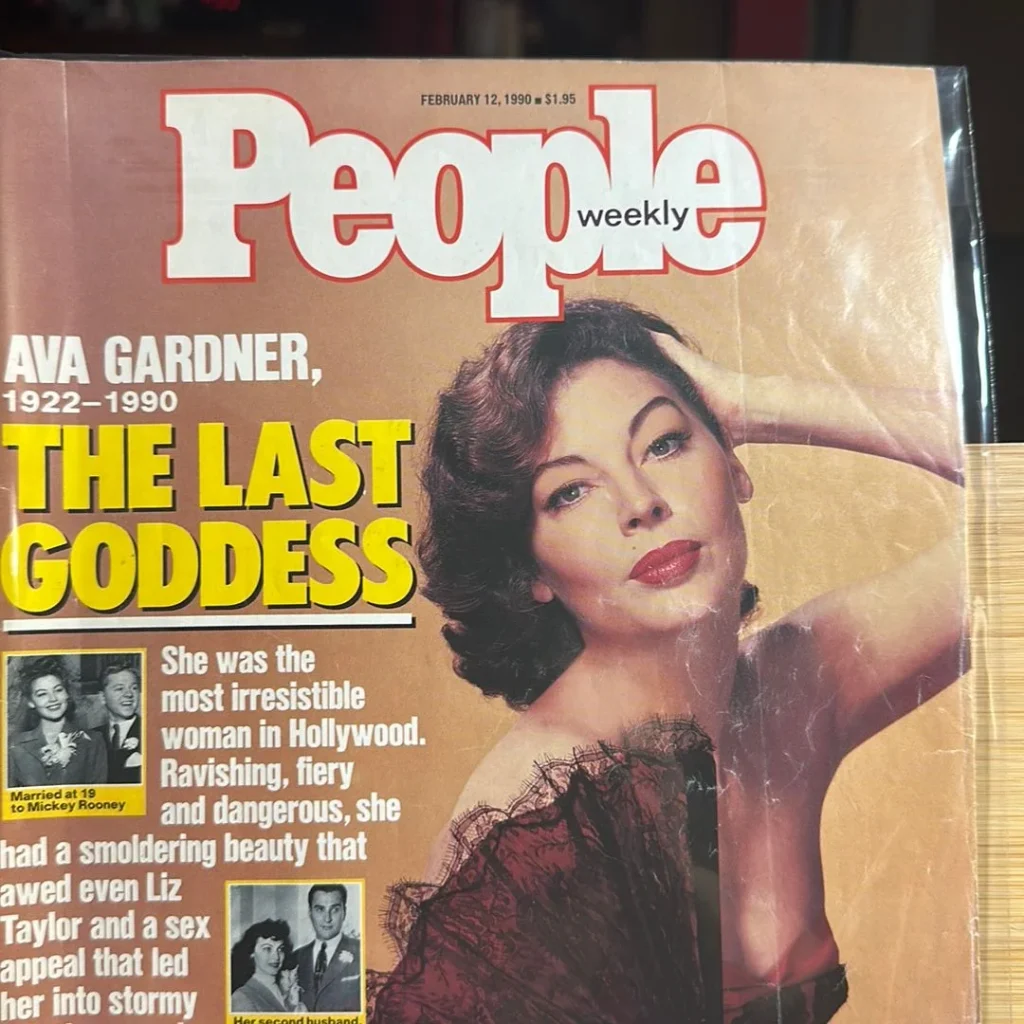

Ava Gardner obituary from “The Los Angeles Times” from 1990.

Ava Gardner the sharecropper’s daughter whose specialty in films was the sloe-eyed sensuous beauty and whose husbands ranged from Mickey Rooney to Frank Sinatra, died Thursday at her home in London.

She was 67 and died of pneumonia, a recurring illness she had been battling for several years. She also suffered a stroke in 1986.

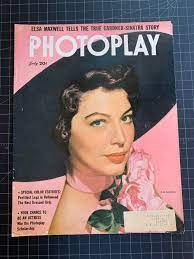

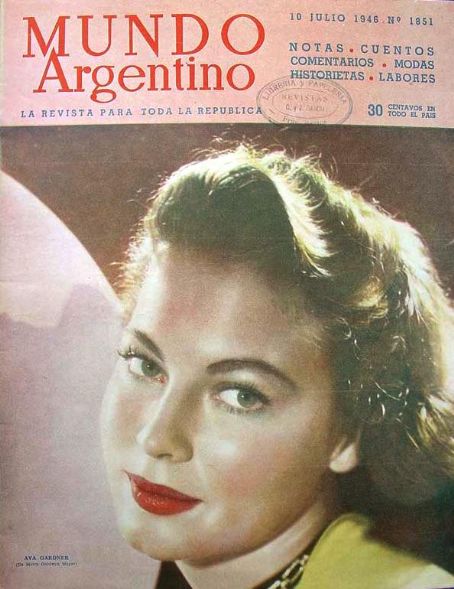

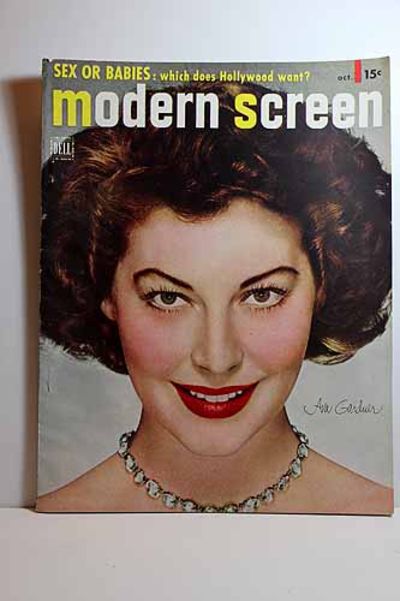

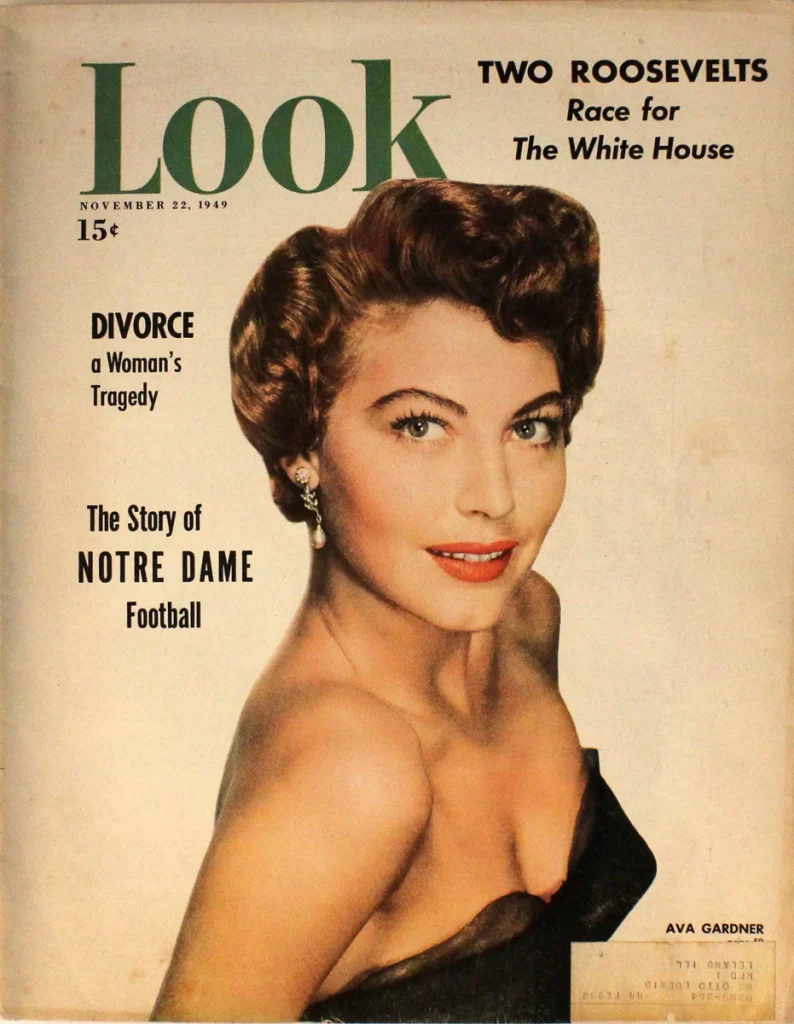

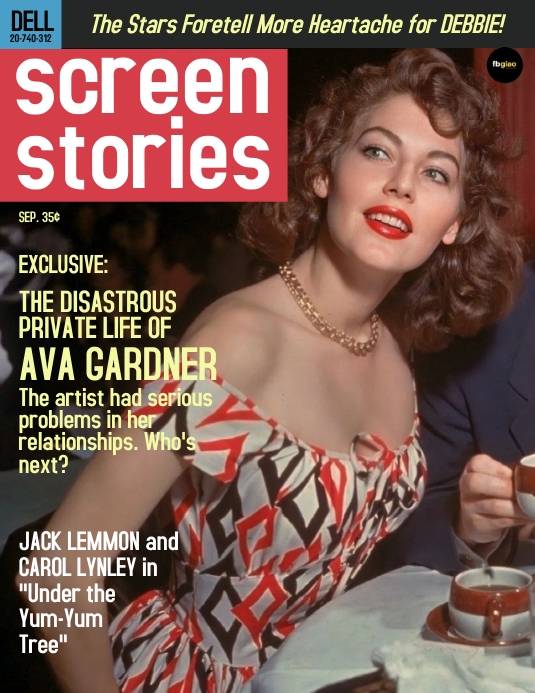

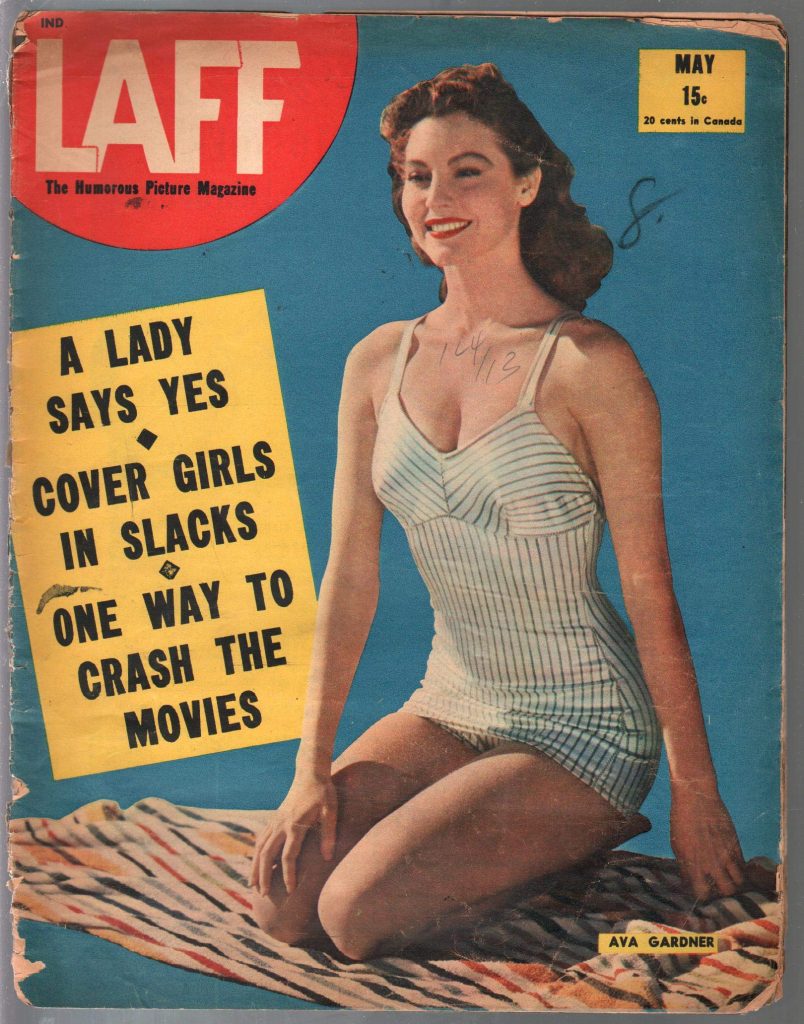

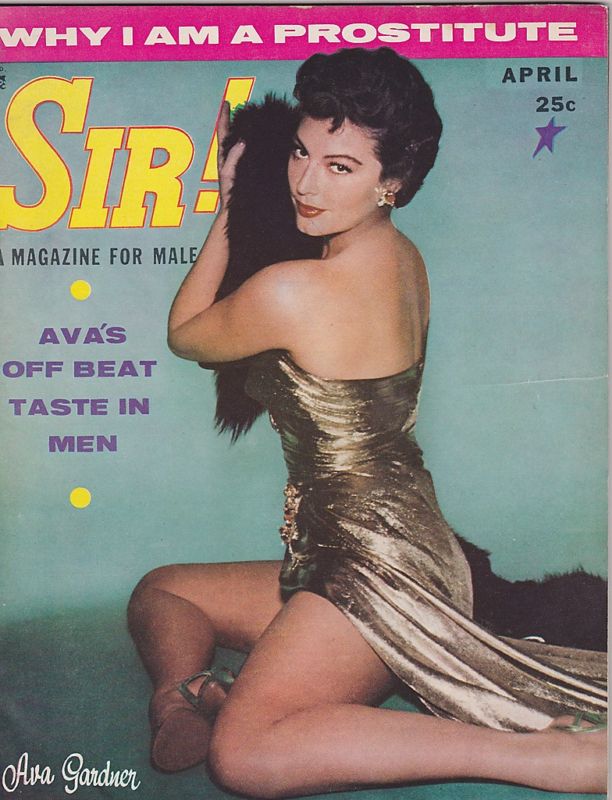

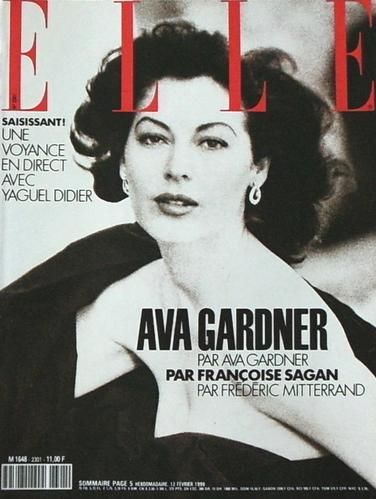

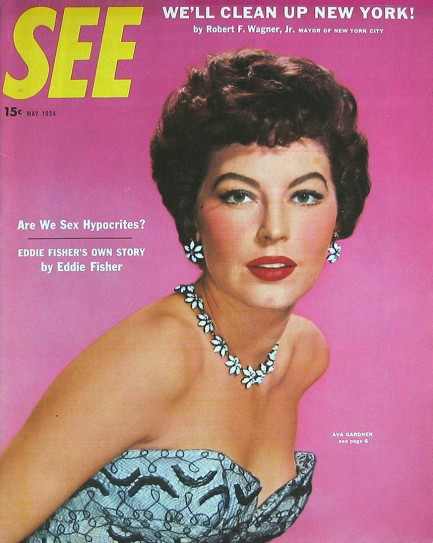

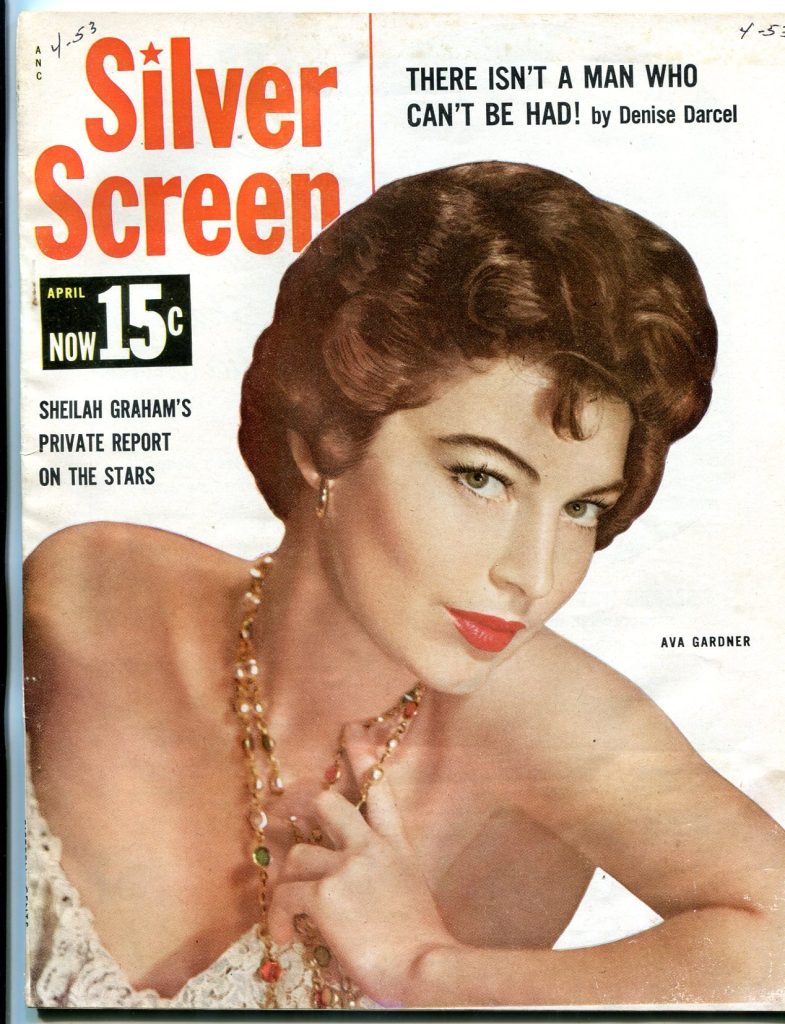

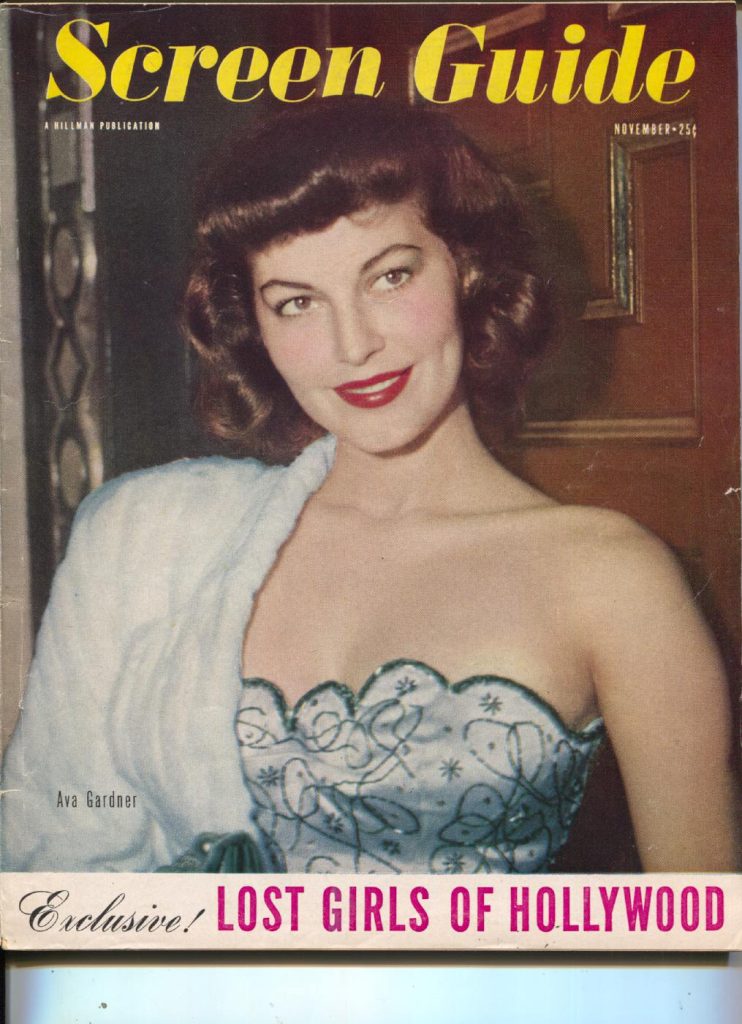

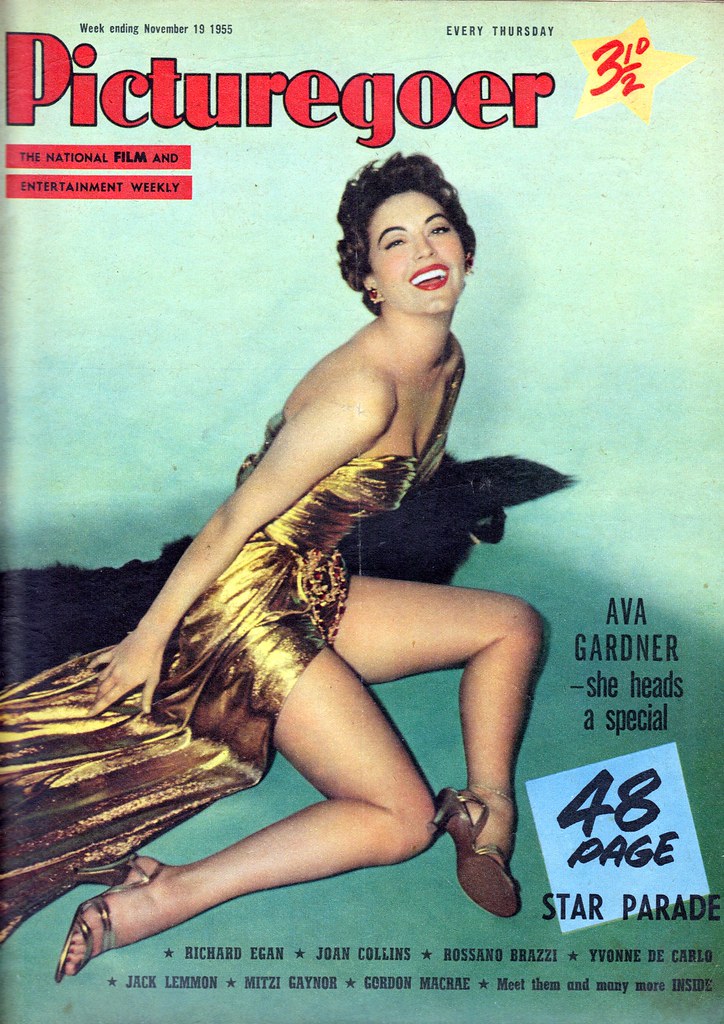

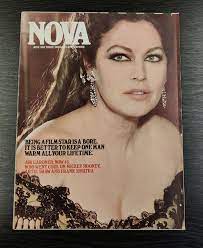

Famed for her green eyes, reddish-brown hair, remarkably photogenic features and understated acting style, she became equally known for the men she attracted. They included orchestra leader Artie Shaw, whom she also married, to Spanish matadors whom she did not.

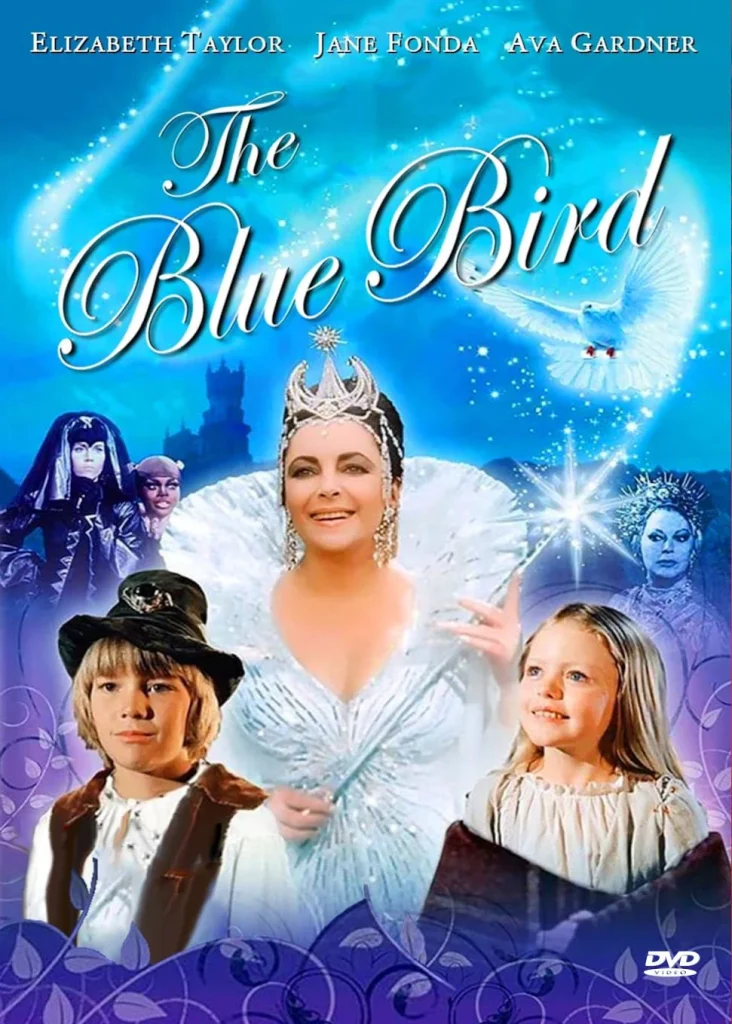

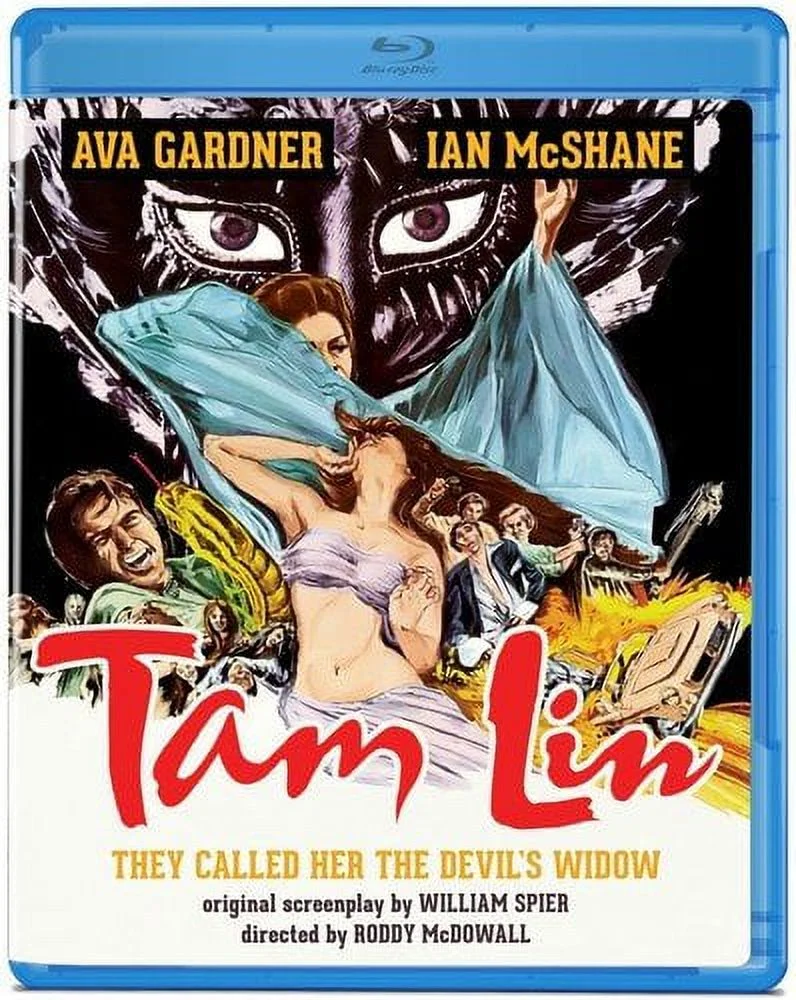

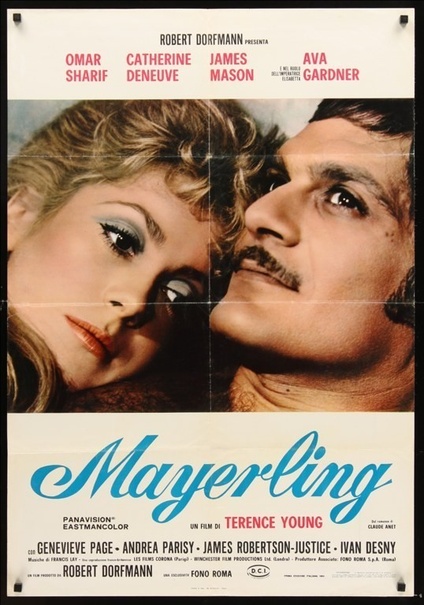

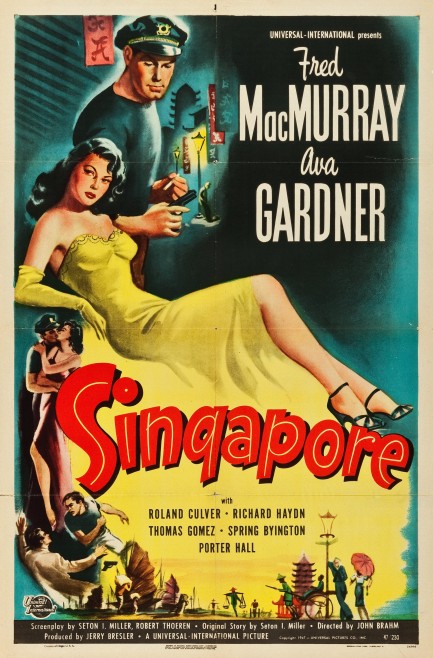

Never considered a great actress in the classic sense of that word, she brought to her more than 60 pictures a magnetic quality that proved box-office prosperity.

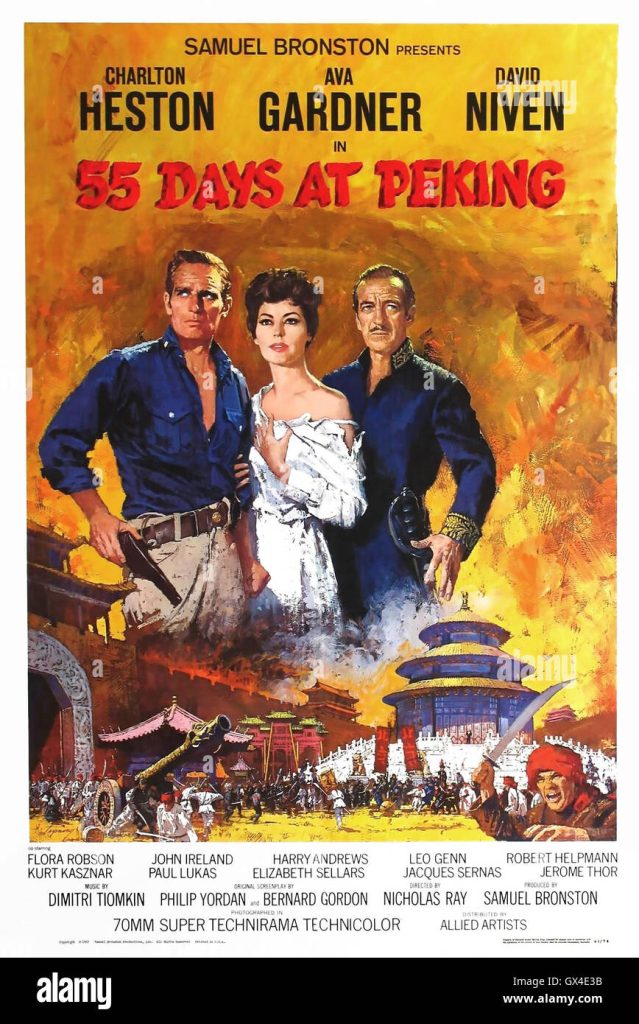

She spanned the generation of sex kittens and love goddesses between Rita Hayworth and Marilyn Monroe before settling in Europe in the 1960s and appearing only occasionally in TV shows and films after that.

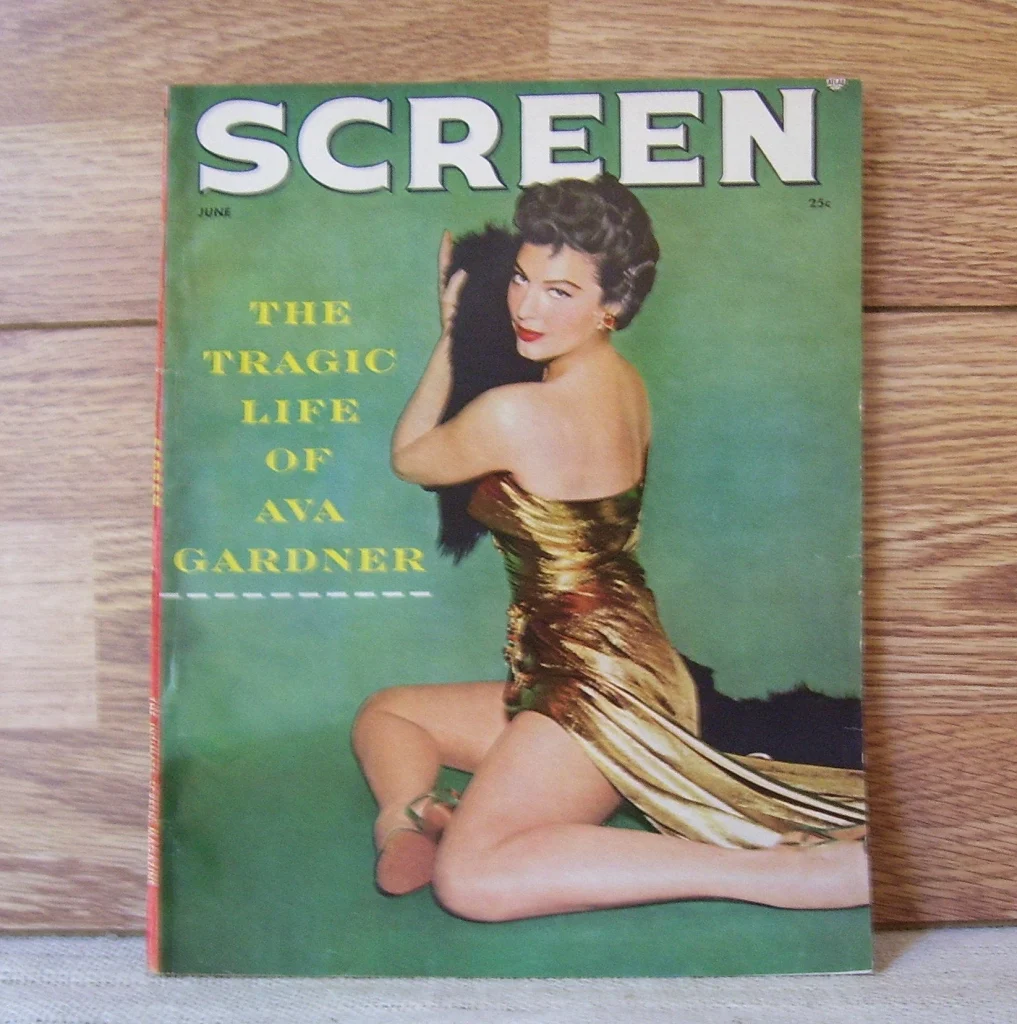

In an interview in 1982, she said she would happily have traded her career for one happy, long-lasting marriage: “One good man I could love and marry and cook for and make a home for, who would stick around for the rest of my life.”

“I never found him,” she said in the interview.

“The trouble was that I was a victim of image,” she said. “Because I was promoted as a sort of siren and played all those sexy broads, people made the mistake of thinking I was like that off the screen.

“They couldn’t have been more wrong. Although no one believes it, I am pathologically shy. I was a country girl and I still have a country girl’s rather simple, ordinary values.”

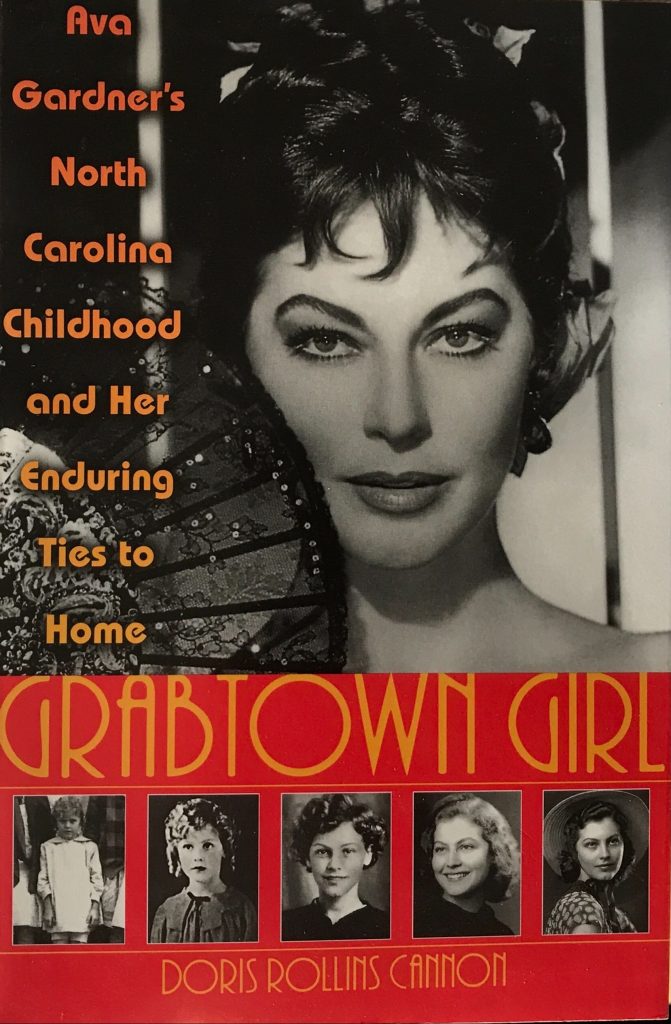

The country girl was indeed that, born Ava Lavinia Gardener near her family’s farm in Smithfield, N.C., on Dec. 24, 1922, the youngest of five children. Her father lost his farm when she was only 2 and was forced to grow tobacco and cotton for shares of those crops.

After her father’s death in 1938, her mother ran a boarding house for minimal money and the young Ava remembered later the taunts of her classmates when she was forced to attend high school in old clothes.

An older brother paid her way to Atlantic Christian College in Wilson, N.C., where she intended to become a stenographer. But on a visit to New York with her sister, her brother-in-law, a commercial photographer, took a number of portraits of her. One of them was sent to Metro Goldwyn Mayer, which ordered a screen test.

It was decided to make the test a silent one because of her pronounced Southern drawl. Despite the limited test, an MGM official supposedly said after viewing it: “She can’t act; she didn’t talk; she’s sensational. Get her out here.”

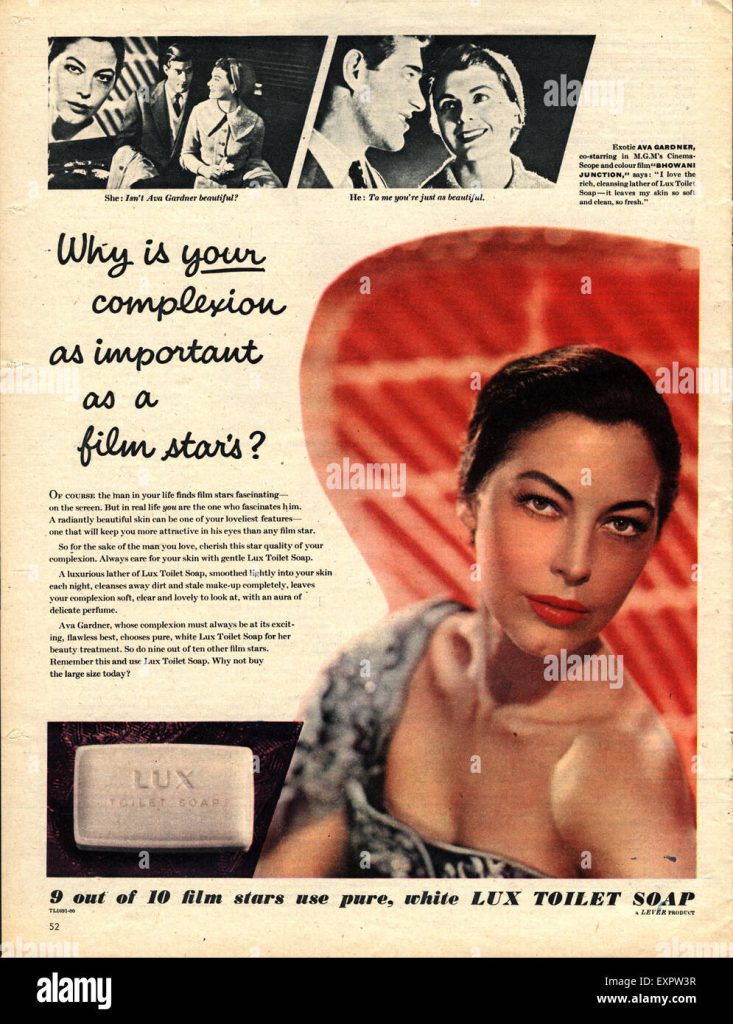

She came to Hollywood under a $50-a-week contract and took diction and acting lessons while posing for the popular cheesecake shots of the time.

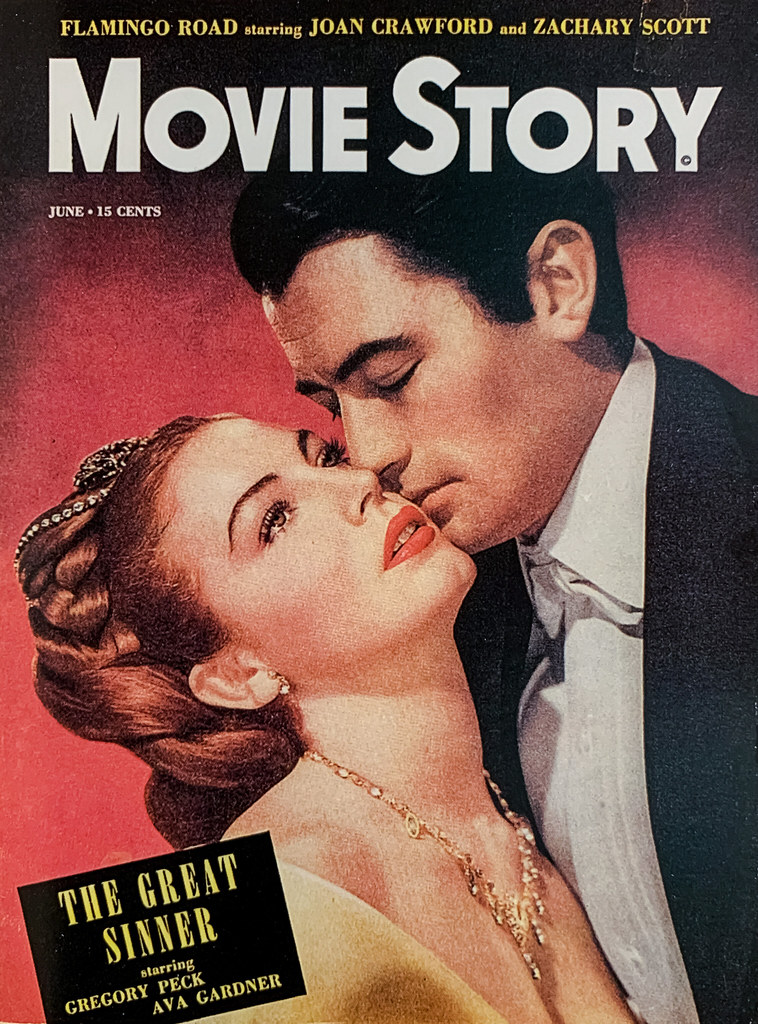

Her first film was “We Were Dancing” in 1942, a stylish romantic comedy with Norma Shearer and Melvyn Douglas.

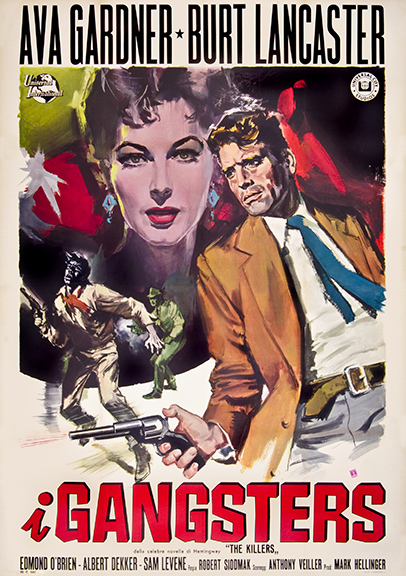

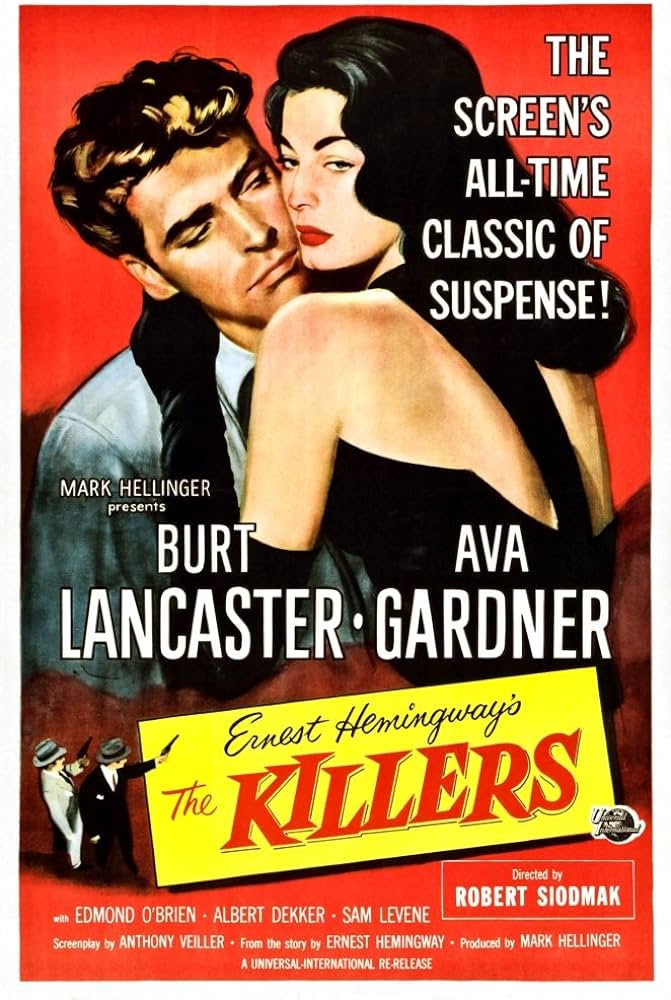

But her reputation as a sex goddess was not fully launched until the 1946 film “The Killers,” in which she co-starred with Burt Lancaster.

Lancaster said in a statement from his Los Angeles home: “She was a wonderful lady, wonderful lady. . . . She was a very simple lady. She used to come down to the beach with us and cook and play with the kids.

“I hope she was happy, that’s all,” he added.

Miss Gardner played a wild Spanish dancer opposite Humphrey Bogart in “The Barefoot Contessa” in 1954 and a love-hungry hotel proprietress chasing Richard Burton in Tennessee Williams’ “Night of the Iguana” 10 years later.

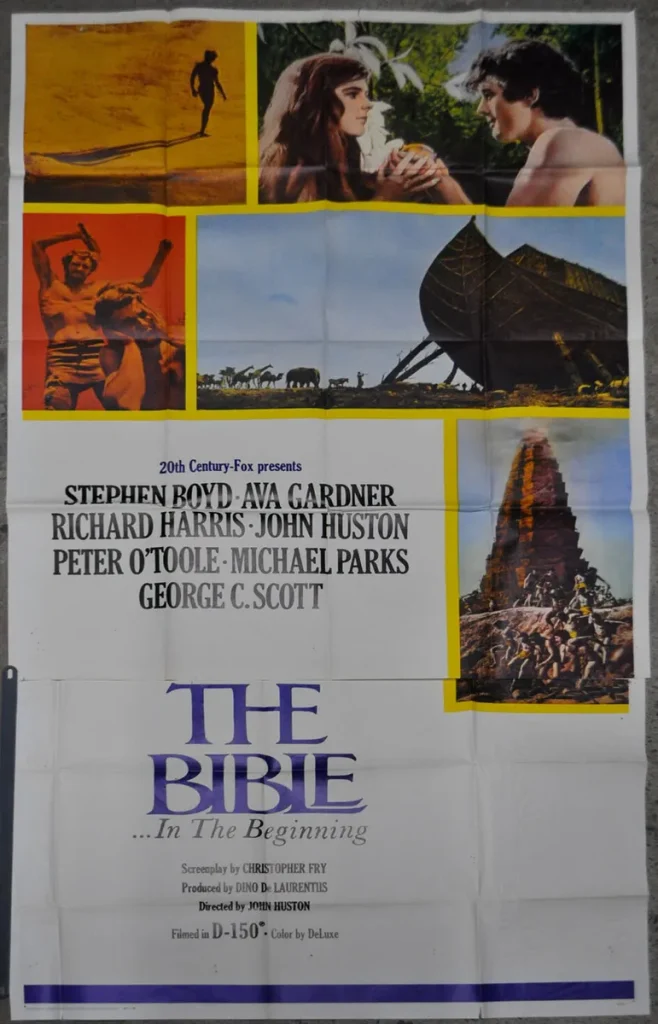

On the set she was known as a nervous actress, who constantly chewed mints or gum but who never seemed in awe of such directors as John Huston, George Cukor and John Ford.

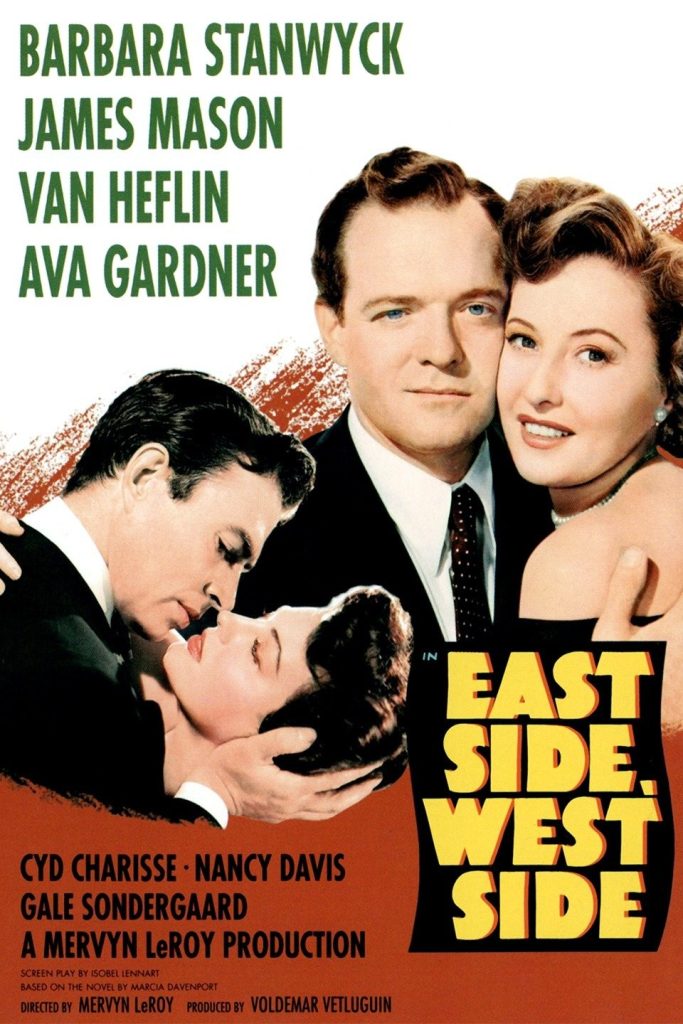

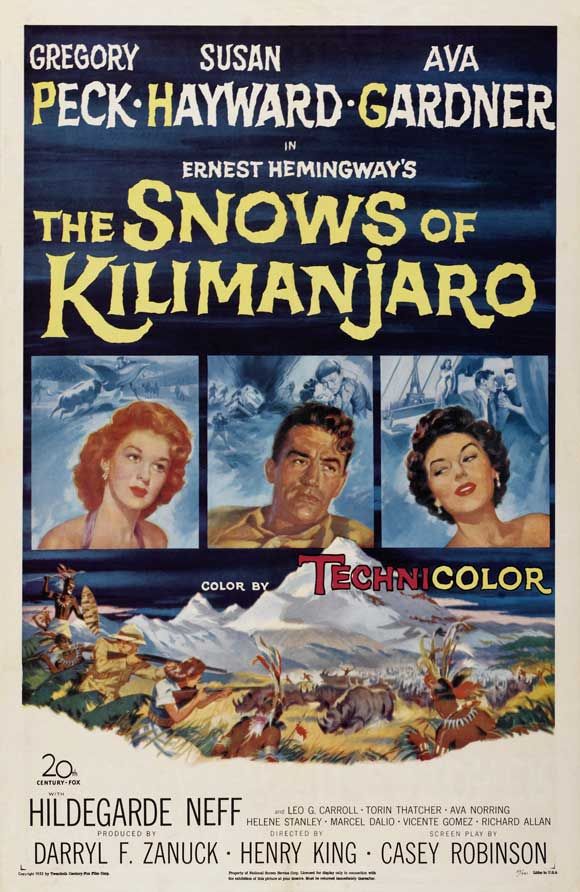

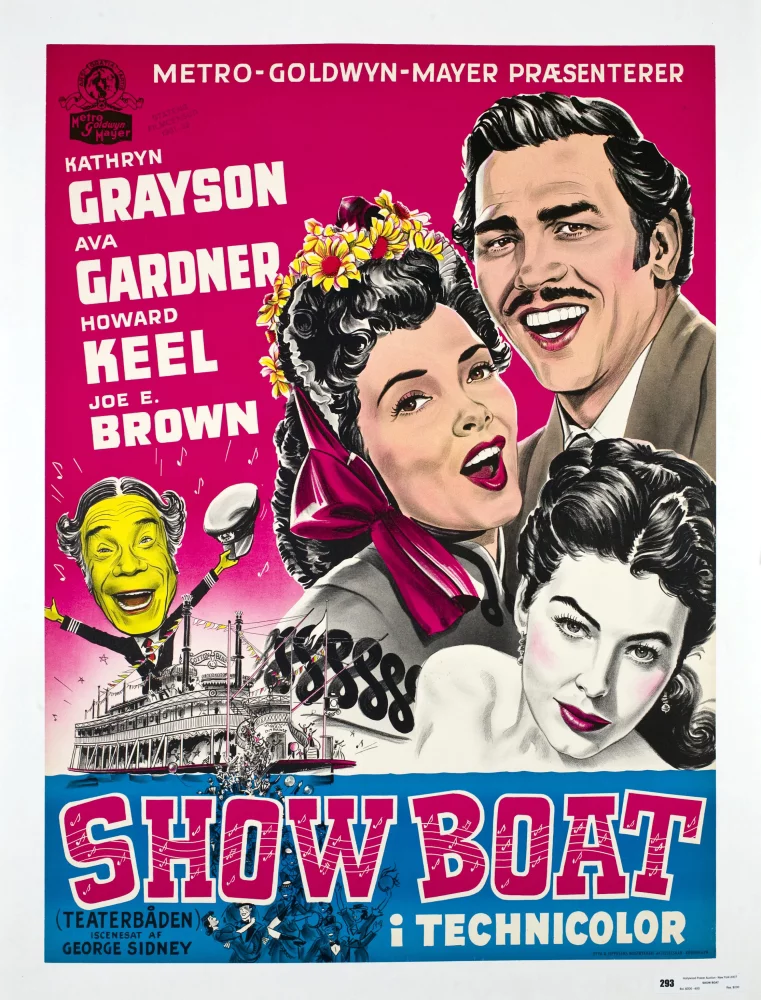

By mid-career she had overcome the shallow roles that fell to her as a girl with appearances in such notable pictures as “Show Boat,” “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” “Mogambo” (her only Oscar nomination) and “On the Beach.”

Her first marriage came in 1942 to fellow MGM stablemate Rooney. He was 21 and at one of several career peaks as the star of the Andy Hardy movies. She was 19. There were reports that Rooney—under orders—took a studio press agent along on their honeymoon. They were divorced after 20 months.

(“My heart is broken with the loss of my first love,” Rooney said from Florida. “The beauty and magic of Ava will forever be in all of our hearts.”)

She met bandleader Shaw at a Hollywood nightclub, and they were married in October, 1945. Shaw took several books to read on their honeymoon and columnists thereafter dwelt on his frustrations in trying to make her more literary. Miss Gardner later suffered a nervous breakdown, and the marriage ended a year after it began.

Between Shaw and Sinatra, her name was linked to billionaire Howard Hughes, at whom she once supposedly launched an ashtray.

She met Sinatra, whose career was in a slump, at a January, 1950, Palm Springs party. Sinatra was married at the time to his childhood sweetheart and wife of 12 years.

Sinatra and Miss Gardner were married in Philadelphia on Nov. 2, 1951.

She obtained a divorce from Sinatra in July, 1957, just as she finished making “The Sun Also Rises,” in which she played the fiery Lady Brett, a seducer of bullfighters.

But she and the singer remained friendly, she said a few years ago, adding that she considered Sinatra “a great artist.”

“Ava was a great lady, and her loss is very painful,” Sinatra told the Associated Press.

She never remarried and in 1958 announced she was quitting MGM.

“MGM was never the right studio for me,” said the outspoken and lightly profane star. “They never bought a property for me; they never knew what to do with me. Most of the time, they loaned me out (to other studios).”

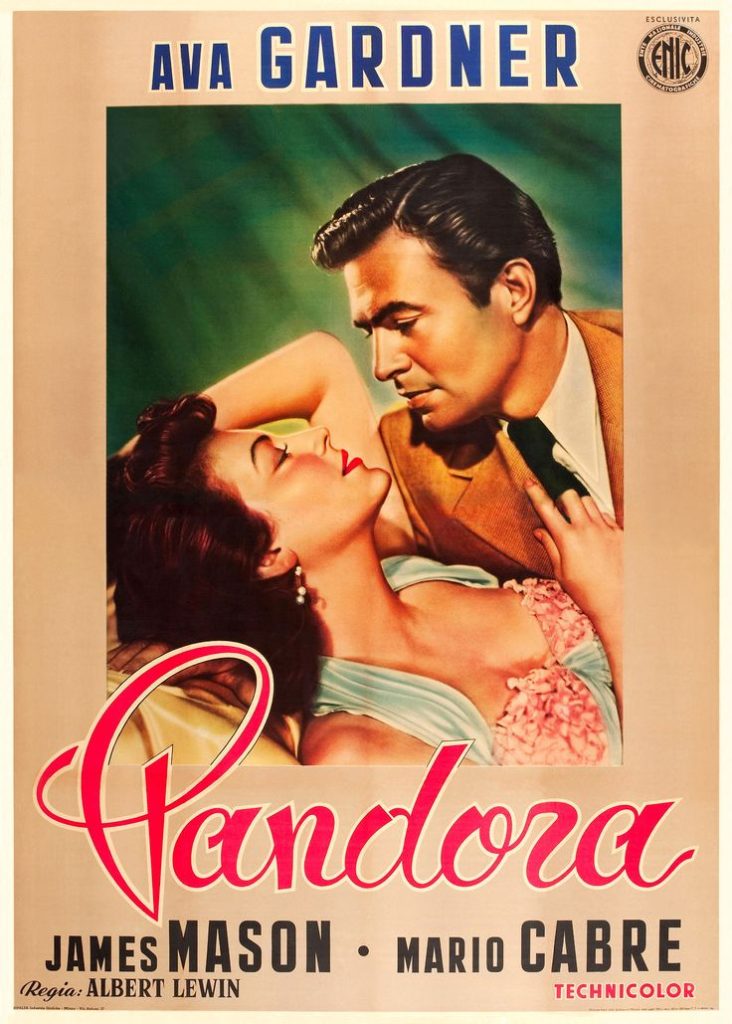

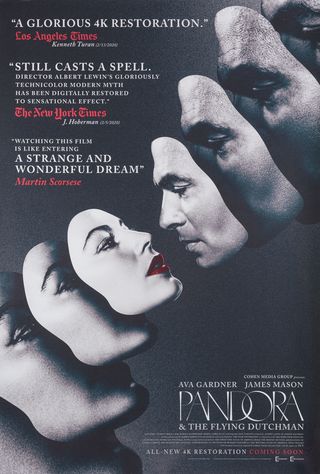

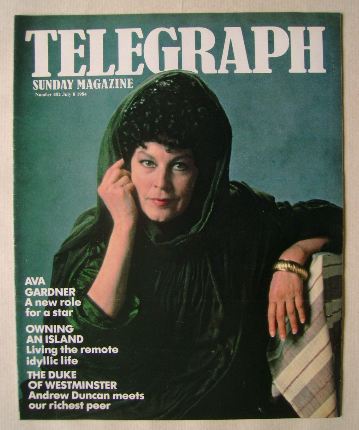

After that, much of her work was done outside the United States and at a tax advantage. She had an elegant apartment near Hyde Park in London and earlier a villa in Madrid. There she was a frequent visitor to the bullrings where she was linked romantically with a succession of toreros, including Mario Cabre and Luis Miguel Dominguin, once rated the No. 1 sword in the world.

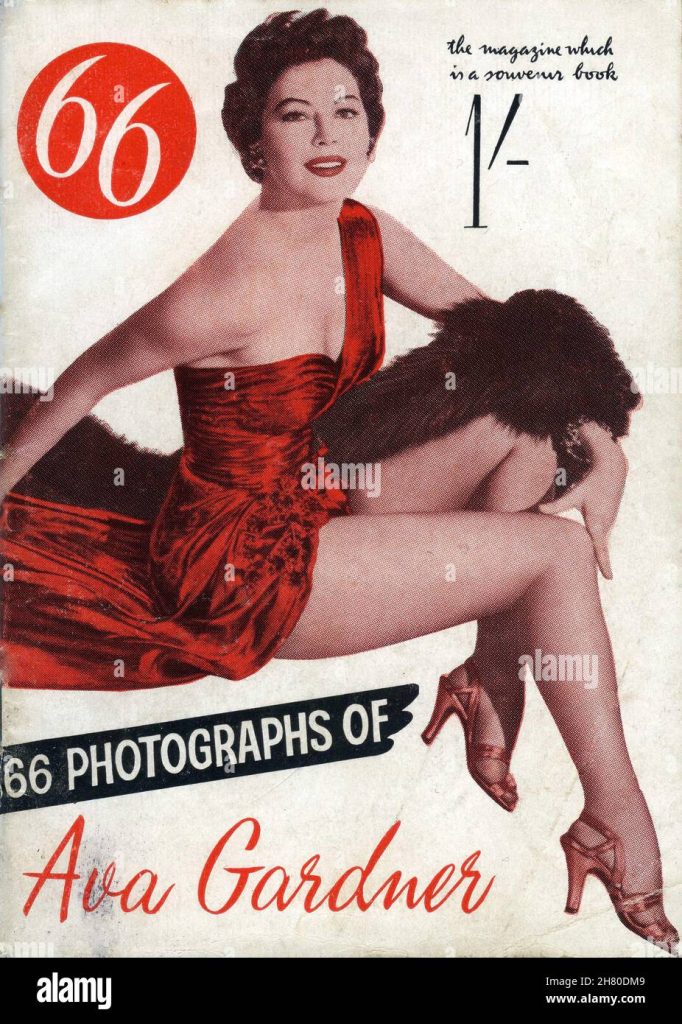

“I was never really an actress,” she said in 1985 in an interview granted in connection with appearances on the CBS-TV series “Knots Landing.”

“None of us kids (including Lana Turner, Judy Garland, Van Johnson and Rooney) that came from MGM were. We were just good to look at.”

A private person even in her youth, she went to extremes to avoid photographers in her later years as she added a few pounds.

But she also maintained a sense of humor about herself, telling a Los Angeles Times interviewer in 1985 that “I look like hell among those babies” (the “Knots Landing” cast.)

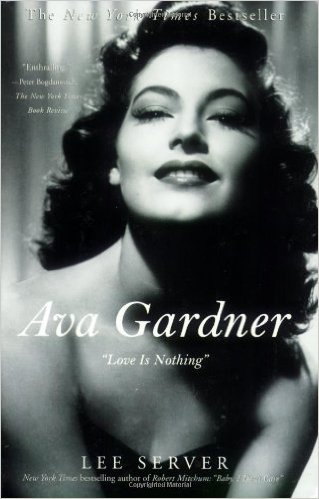

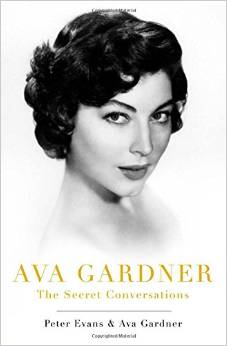

There were dozens of articles and at least one book written about her and she once threatened to write one of her own, saying that her words had been twisted throughout her life.

“But I probably won’t . . . I’m too lazy.”

Her old neighbors in North Carolina created a museum that contained many of the pictures and memorabilia of their farm girl-become-movie-queen. There were mannequins and several of her film costumes.

But the subject of their adulation never went inside the old wooden building in Brogden, N.C., near Raleigh.

“I know what’s in there,” she told a Times reporter on a visit to her birthplace in 1984.

“I lived it.”

Her body will be taken to Smithfield for burial alongside her parents.