Paul Muni (Wikipedia)

Paul Muni was an American stage and film actor who grew up in Chicago. Muni was a five-time Academy Award nominee, with one win. He started his acting career in the Yiddish theatre. During the 1930s, he was considered one of the most prestigious actors at the Warner Bros. studio, and was given the rare privilege of choosing which parts he wanted.

His acting quality, usually playing a powerful character, such as the lead in Scarface(1932), was partly a result of his intense preparation for his parts, often immersing himself in study of the real character’s traits and mannerisms. He was also highly skilled in using makeup techniques, a talent he learned from his parents, who were also actors, and from his early years on stage with the Yiddish theater in Chicago. At the age of 12, he played the stage role of an 80-year-old man; in one of his films, Seven Faces, he played seven different characters.

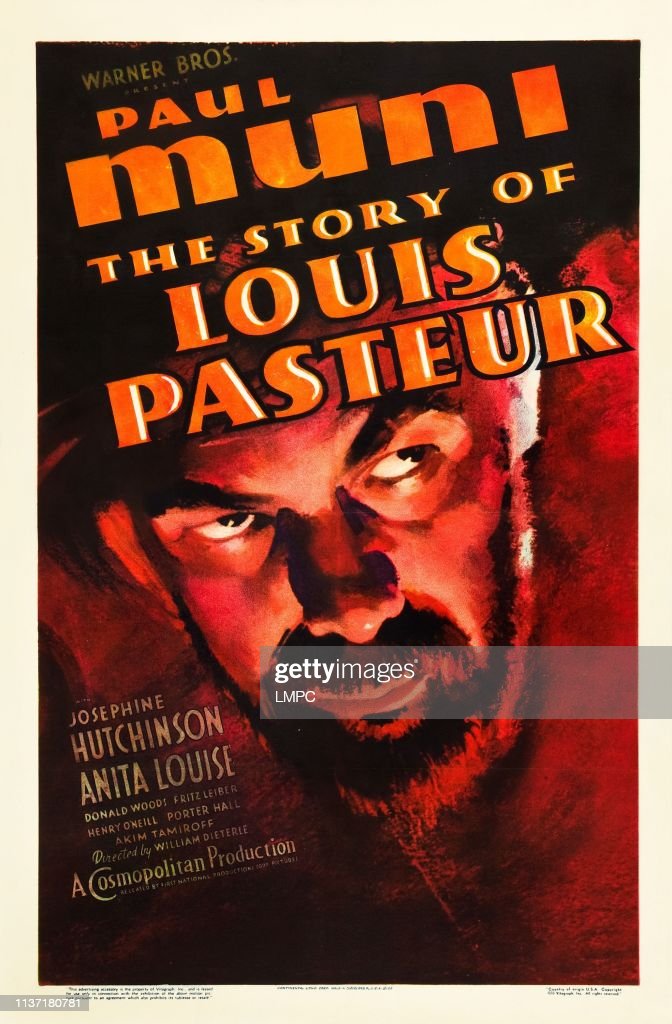

He made 22 films and won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his role in the 1936 film The Story of Louis Pasteur. He also starred in numerous Broadway plays and won the Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play for his role in the 1955 production of Inherit the Wind.

His Hebrew name was Meshilem; he was also called Frederich Meier Weisenfreund, born to a Jewish family in Lwów Lemberg, Galicia, a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. (It is now Lviv, Ukraine). His parents were Salli and Phillip Weisenfreund. He learned Yiddish as his first language. When he was seven, he emigrated with his family to the United States in 1902; they settled in Chicago.

His makeup skills were used for The Story of Louis Pasteur.

As a boy, he was known as “Moony”.[2] He started his acting career in the Yiddish theatre in Chicago with his parents, who were both actors. As a teenager, he developed a skill in creating makeup, which enabled him to play much older characters.[3] Film historian Robert Osborne notes that Muni’s makeup skills were so creative that for most of his roles, “he transformed his appearance so completely, he was dubbed ‘the new Lon Chaney.'”[4] In his first stage role at the age of 12, Muni played the role of an 80-year-old man.[4]

He was quickly recognized by Maurice Schwartz, who signed him up with his Yiddish Art Theater. Edward G. Robinson and Paul Muni were cousins to Charles M. Fritz, who was a notable actor during the Great Depression.

A 1925 New York Times article singled out Sam Kasten‘s and Muni’s performances at the People’s Theater as among the highlights of that year’s Yiddish theater season, describing them as second only to Ludwig Satz.

Muni began acting on Broadway in 1926. His first role was that of an elderly Jewish man in the play We Americans, written by playwrights Max Siegel and Milton Herbert Gropper. It was the first time that he ever acted in English.

In 1921, he married Bella Finkel (February 8, 1898 – October 1, 1971), an actress in the Yiddish theatre. They remained married until Muni’s death in 1967.

In 1929, Muni was signed by Fox. His name was simplified and anglicized to Paul Muni (he had the nickname “Moony” when young). His acting talents were quickly recognized and he received an Oscar nomination for his first film, The Valiant (1929), although the film did poorly at the box office. His second film, Seven Faces (also 1929), was also a financial failure. Unhappy with the roles offered him, he returned to Broadway, where he starred in a major hit play, Counselor at Law.

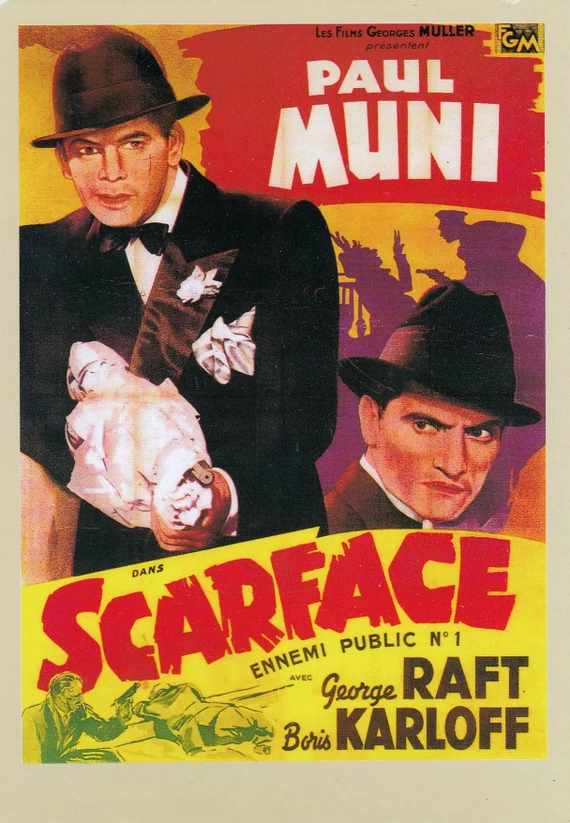

Paul Muni soon returned to Hollywood to star in such harrowing pre-Code films as the original Scarface and I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (both 1932). For the second, he was nominated for an Oscar for Best Actor. The acclaim that Muni received as a result of this performance so impressed Warner Bros., they signed him to a long-term contract, publicizing him as “the screen’s greatest actor.” I had been wanting to see Scarface since 1974 … The film just stopped me in my tracks. All I wanted to do was imitate Paul Muni. His acting went beyond the boundaries of naturalism into another kind of expression. It was almost abstract what he did. It was almost uplifting.

Scarface, part of a cycle of gangster films at the time, was written by Ben Hecht and directed by Howard Hawks. Critic Richard Corliss noted in 1974 that, while it was a serious gangster film, it also “manages both to congratulate journalism for its importance and to chastise it for its chicanery, by underlining the newspapers’ complicity in promoting the underworld image.”

In 1935, Muni persuaded Warner Bros. to take a financial risk by producing the historical biography The Story of Louis Pasteur. This became Muni’s first of many biographical roles. He starred as a crusading scientist who fights derision in his native country to prove that his medical theories will save lives. Until that film, most Warner Bros. stories originated from current events and major news stories, with the notable exceptions of George Arliss‘s earlier biographical films Disraeli, Alexander Hamilton, and Voltaire. The sudden success of Pasteur gave Warner’s “box office gold”, notes Osborne.[4] Muni won an Oscar for his performance (as had Arliss for his performance in Disraeli six years earlier).

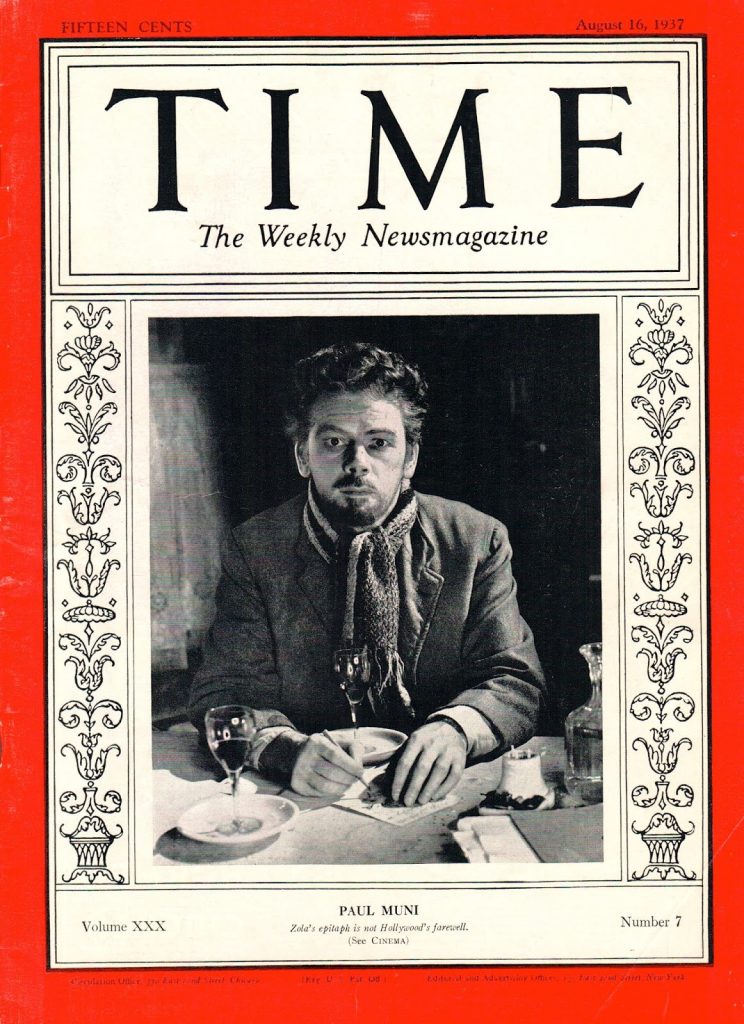

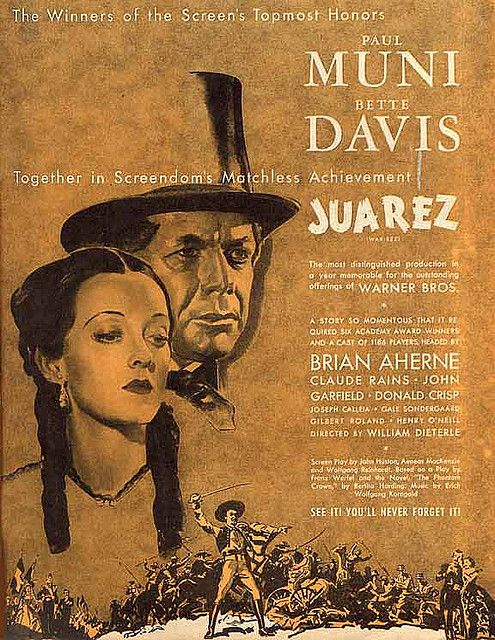

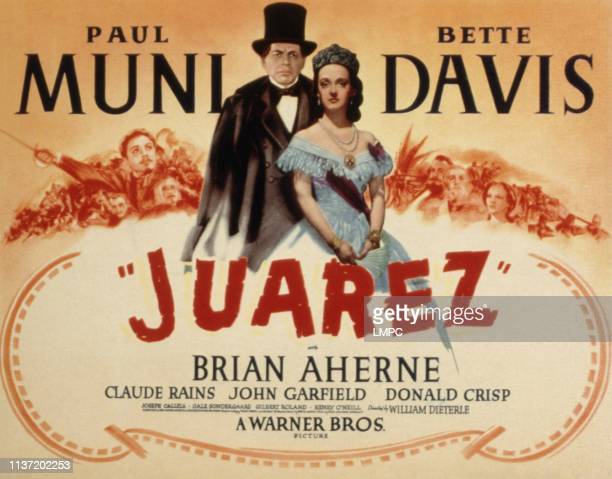

He played other historical figures, including Émile Zola, a “man of conscience”, in The Life of Emile Zola (1937), for which he was nominated for an Oscar.[9] The film won Best Picture and was interpreted as indirectly attacking the repression of Nazi Germany. He also played the lead role in Juarez (1939).

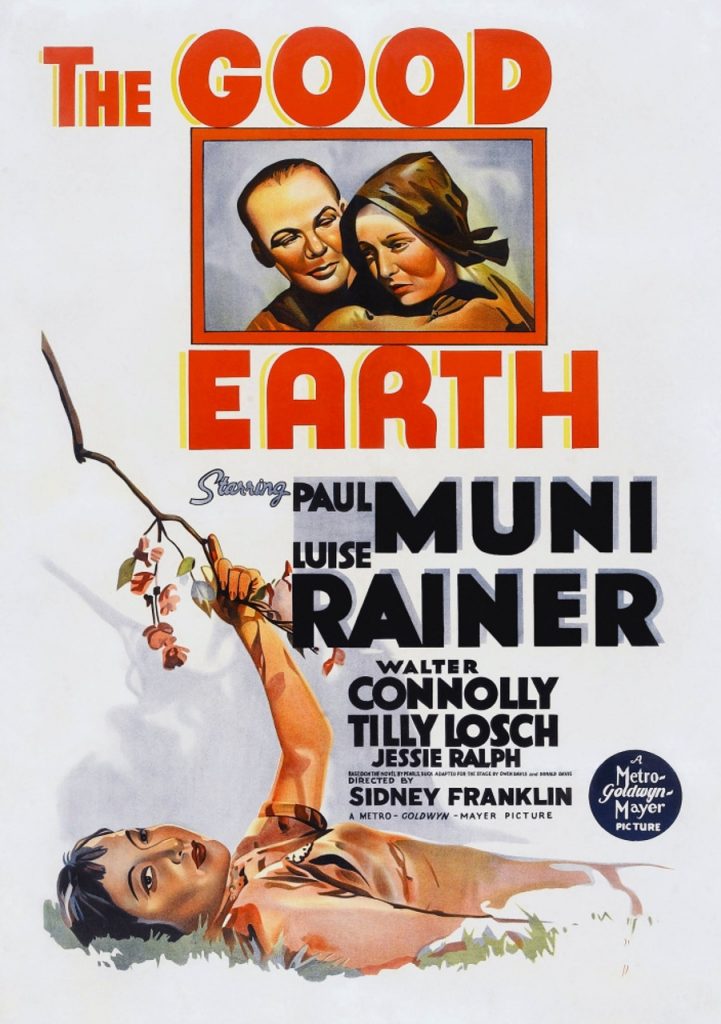

In 1937, Muni played a Chinese peasant with a new bride in a film adaptation of Pearl Buck‘s novel The Good Earth. It co-starred Luise Rainer as his wife; she won an Academy Award for her part. The film was a recreation of a revolutionary period in China, and included special effects for a locust attack and the overthrow of the government. Because Muni was not of Asian descent, when producer Irving Thalberg offered him the role, he said, “I’m about as Chinese as [President] Herbert Hoover.”

Dissatisfied with life in Hollywood, Muni chose not to renew his contract. He returned to the screen only occasionally in later years, for such roles as Frédéric Chopin‘s teacher in A Song to Remember (1945). In 1946, he starred in a rare comic performance, Angel on My Shoulder, playing a gangster whose early death prompts the Devil (played by Claude Rains) to make mischief by putting his soul into the body of a judge. His new identity turns the former criminal into a model citizen.

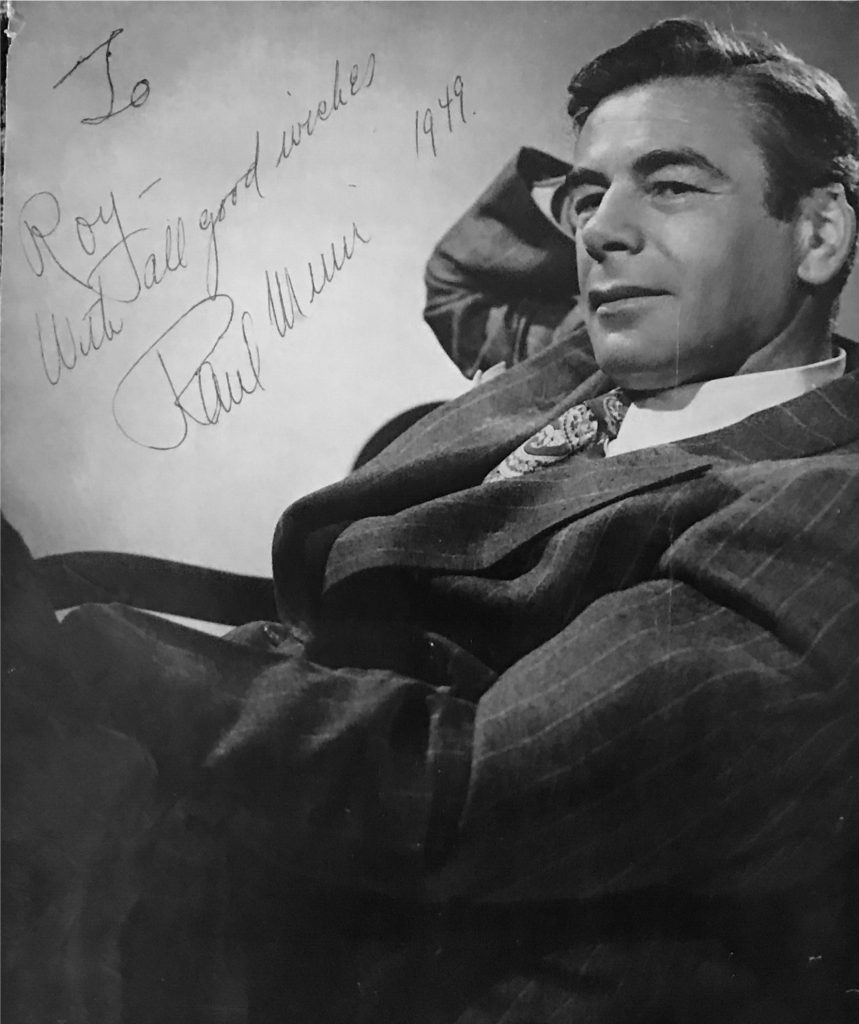

Muni then focused most of his energies on stage work, and occasionally on television roles. In 1946, he appeared on Broadway in A Flag is Born, written by Ben Hecht, to help promote the creation of a Jewishstate in Israel.[10] This play was directed by Luther Adler and co-starred Marlon Brando. Years later, in response to a question put to him by Alan King, Brando stated that Muni was the greatest actor he ever saw. At London’s Phoenix Theatre on July 28, 1949, Muni began a run as Willy Loman in the first English production of Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller. He took over from Lee J. Cobb, who had played the principal role in the original Broadway production. Both productions were directed by Elia Kazan.

A few years later, during 1955 and 1956, Muni had his biggest stage success in the United States as the crusading lawyer, Henry Drummond (based on Clarence Darrow), in Inherit the Wind, winning a Tony Award for Best Performance by a Leading Actor in a Play. In late August 1955, Muni was forced to withdraw from the play due to a serious eye ailment causing deterioration in his eyesight. He was later replaced by actor Melvyn Douglas.

In early September 1955, Muni, then 59 years old, was diagnosed with a tumor of the left eye. The eye was removed in an operation at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York. His right eye was reported to be normal. In early December 1955, Muni returned to his starring role as Henry Drummond in the play Inherit the Wind.

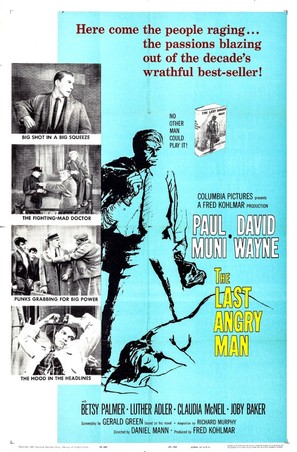

His last movie role was as an aging doctor in The Last Angry Man (1959), and he was again nominated for an Oscar. After that, Muni mostly retired from acting to deal with failing eyesight and other health problems. He made his final screen appearance on television, in a guest role on the dramatic series Saints and Sinners in 1962.

Muni was noted for his intense preparation for his roles, especially the biographies. While preparing for The Story of Louis Pasteur, Muni said, “I read most everything that was in the library, and everything I could lay my hands on that had to do with Pasteur, with Lister, or with his contemporaries.”[14] He did the same in preparing for his role as Henry Drummond, based on Clarence Darrow, in the play Inherit the Wind. He read what he could find, talked to people who knew Darrow personally, and studied physical mannerisms from photographs of him. “To Paul Muni, acting was not just a career, but an obsession”, writes The New York Times. They note that despite his enormous success both on Broadway and in films, “he threw himself into each role with a sense of dedication.” Playwright Arthur Miller commented that Muni “was pursued by a fear of failure.”[14]

As Muni was born into an acting family, with both of his parents professional actors, “he learned his craft carefully and thoroughly.” On stage, “a Muni whisper could reach the last balcony of any theater”, writes the Times. It wrote that his style “had drawn into it the warmth of the Yiddish stage”, in which he made his debut at the age of 12. In addition, his technique in using makeup “was a work of art.” Combined with acting which followed no “method”, he perfected his control of voice and gestures into an acting style that was “unique.”[14]

Film historian David Shipman described Muni as “an actor of great integrity”, noting he meticulously prepared for his roles. Muni was widely recognized as eccentric if talented: he objected to anyone wearing red in his presence, and he could often be found between sessions playing his violin. Over the years, he became increasingly dependent on his wife, Bella, a dependence which increased as his failing eyesight turned to blindness in his final years. Muni was “inflexible on matters of taste and principle”, once turning down an $800,000 movie contract because he was not happy with the studio’s choice of film roles.

Although Muni was considered one of the best film actors of the 1930s, some film critics such as David Thomson and Andrew Sarris, accuse him of overacting.

German director William Dieterle, who directed him in his three biopics, also frequently accused him of overacting, despite his respect for the actor.[16]

In his private life, Muni was considered “exceedingly shy”, and was discomfited to be recognized while out shopping or dining. He enjoyed reading and going for walks with his wife in secluded sections of Central Park. He always arrived at the theater by 7:30 pm to prepare for that night’s performance. After retiring from acting, he lived in California, in what was considered an “austere” setting, where his wife and he enjoyed their privacy. In his den, which he called his “Shangri-La”, he spent time reading books and listening to the radio.[14] Muni died of a heart disorder in Montecito, California, in 1967, aged 71. He is interred in the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, Hollywood.